“I am now Imbarked on a tempestuous Ocean from whence, perhaps, no friendly harbor is to be found.”

George Washington to Burrell Bassett, June 19, 1775

yesyesyes

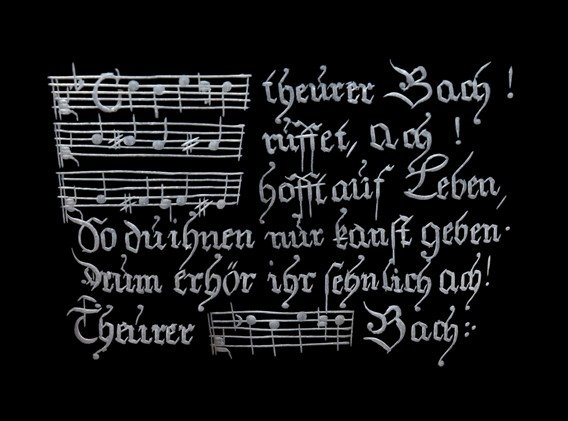

In German usage the note B flat is called B, and B natural is called H. This allows Bach’s name to be expressed as a musical motif, B flat-A-C-B natural and the composer himself used it in one of the fugue subjects of the final (“unfinished”) contrapunctus in his Art of Fugue. What ideas, does this work of Bach convey? Albert Schweitzer characterized it in the following strange way: “Really, this theme cannot be called interesting; it seems not to have been born of some intuitive genius, but rather invented for the sake of its subsequent thorough development and inversion. And yet, it transfixes the attention of anyone who hears it. A quiet world opens before us, a serious world, desert-like, deathly cold, colorless, gloomily without motion, it does not gladden or entertain. And yet, we cannot tear ourselves away from the theme.” Throughout the cycle, the theme is varied: Here is the form it takes in inversion (where the melody becomes like a mirror reflection: what went upwards, now goes downwards, and vice versa) What ideas, does this work of Bach convey? There is a halo of mystery around the cycle: it appears to be unfinished, and the final fugue breaks off literally in mid-measure. The manuscript makes it possible to imagine, that you are as if present with the composer in his creative process, at the moment of creation. You see how he writes, and then corrects what he has written; it seems that the composition is finished, but then suddenly he adds two measures. This is an extremely engrossing task to understand, why he did it this way, and not some other way, or what a new version gives, by comparison with the first draft, or why the fugues are ordered in the autograph, differently from their order in the finished cycle, even in the first part, which Bach sanctioned. Why are some of them written out in a strange way, not in succession, but one under the other?

“You can write sounds?”

The amazing unity and dramatic wholeness of this cycle, have naturally prompted attempts to search out the hidden thought-content of the conception. Erich Schwebsch considered that the cycle embodies the birth of the personality and self-consciousness, personified by the theme B-A-C-H. Bach placed this musical theme-symbol of his name at the end of the work, like a kind of author’s signature, but he prepared this moment throughout the entire cycle, introducing this theme in more or less covert form. Schwebsch’s idea was further developed in the conception of Erich Bergel on the polarity and unity of two spiritual spheres—the human and the divine, the cosmic, incarnated by the chromatic (in the BACH theme), and this diatonic music of the main theme. Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht looked at the BACH theme in the Final Fugue, together with its continuation. This researcher especially emphasized the theme’s striving toward the main tonic of the cycle— “D.” While Schwebsch had written about this as follows: “Just as Bach himself stood at the threshold in 1750, so The Art of the Fugue is spiritually located between the Cosmos and “I”-ness [individuality]. Only someone with the heart of Bach would, in the face of death, dare to place his ‘I’ as representative of the center of a universal development. Eggebrecht suggests, that “here Bach’s intention was not to say I, BACH, composed this, but rather he wanted to indicate: I, BACH, am bound up with the tonic and will attain it.” Eggebrecht explains the significance of this tonic (“God”) [“D”— Deo], with reference to the chorale “Vor Deinem Thron tret ich hiermit” (“I come before Thy throne”), which expresses the idea of the transit from this world to the next.

Under mescalin it happens that approaching objects appear to grow smaller. A limb or other part of the body, the hand, mouth or tongue seems enormous, and the rest of the body is felt as a mere appendage to it. The walls of the room are 150 yards apart, and beyond the walls is merely an empty vastness. The extended hand is as high as the wall, and external space and bodily space are divorced from each other to the extent that the subject has the impression of eating ‘from one dimension to the other’. Sometimes motion is no longer seen, and people seem to be transported magically from one place to another. The subject is alone and forlorn in empty space, ‘he complains that all he can see clearly is the space between things, and that this space is empty. Objects are in a way still there, but not as one would expect. . . .’ Men are like puppets and their movements are performed in a dreamlike slow-motion. The leaves on the trees lose their framework and organization: every point on the leaf has the same value as every other. One schizophrenic says:

A bird is twittering in the garden. I can hear the bird and I know that it is twittering, but that it is a bird and that it is twittering, the two things seem so remote from each other. . . .there is a an abyss… as if the bird and the twittering had nothing to do with each other.

Another schizophrenic can no longer manage to ‘understand’ the clock, that is, in the first place the movement of the hands from one position to another, and especially the connection of this movement with the drive of the mechanism, the ‘working’ of the clock.

These disturbances do not affect perception as knowledge of the world: the oversized parts of the body, the too small objects near at hand are not posited as such; for the patient the walls of the room are not far from each other as are the two ends of a football field for a normal person. The subject is well aware that his food and his own body reside in the same space, since he takes food with his hand. Space is ‘empty’, and yet all the objects of perception are there. The disturbance does not bear upon the information one can draw from perception, and it reveals a deeper life of consciousness beneath “perception”. Even where there is failure to perceive, as with regard to movement, the perceptual deficiency appears as no more than an extreme case of a more general disturbance of the process of relating phenomena to each other. There is a bird and there is twittering, but the bird no longer twitters. There is a movement of the clock hands, and a spring, but the clock no longer ‘goes’. In the same way certain parts of the body are enlarged out of all proportion, and adjacent objects made too small because the whole picture no longer forms a system. Now, if the world is atomized or dislocated, this is because one’s own body has ceased to be a knowing body, and has ceased to draw together all objects in its one grip; and this debasement of the body into an organism must itself be attributed to the collapse of time, which no longer rises towards a future but falls back on itself.

Once I was a man, with a soul and a living body (Leib) and now I am no more than a being (Wesen). . . . Now there remains merely the organism (Körper) and the soul is dead. . . . I hear and see, but no longer know anything, and living is now a problem for me. . . . I now live on in eternity. . . . The branches sway on the trees, other people come and go in the room, but for me time no longer passes. . . . Thinking has changed, and there is no longer any style. . . . What is the future? It can no longer be reached. . . . Everything is in suspense. . . . Everything is monotonous, morning, noon, evening, past, present and future. Everything is constantly beginning all over again.

He watched her pour into the measure and thence into the jug rich white milk, not hers. Old shrunken paps. She poured again a measureful and a tilly. Old and secret she had entered from a morning world, maybe a messenger. She praised the goodness of the milk, pouring it out. Crouching by a patient cow at daybreak in the lush field, a witch on her toadstool, her wrinkled fingers quick at the squirting dugs. They lowed about her whom they knew, dewsilky cattle. Silk of the kine and poor old woman, names given her in old times. A wandering crone, lowly form of an immortal serving her conqueror and her gay betrayer, their common cuckquean, a messenger from the secret morning. To serve or to upbraid, whether he could not tell: but scorned to beg her favour.

I now think it was a great mistake to move east again and have her go

to that private school in Beardsley, instead of somehow scrambling across the Mexican border while the scrambling was good so as to lie low for a couple of years in subtropical bliss until I could safely marry my little Creole; for I must confess that depending on the condition of my glands and ganglia, I could switch in the course of the same day from one pole of insanity to the other–from the thought that around 1950 I would have to get rid somehow of a difficult adolescent whose magic nymphage had evaporated–to the thought that with patience and luck might have her produce eventually a nymphet with my blood in her exquisite veins, a Lolita the Second, who would be eight or nine around 1960, when I would still be dans la force de l’áge; indeed, the telescopy of my mind, or un-mind, was strong enough to distinguish in the remoteness of time a vieillard encore vert–or was it green rot?–bizarre, tender, salivating Dr. Humbert, practicing on supremely lovely Lolita the Third the art of being a granddad.

In the days of that wild journey of ours, I doubted not that as father

to Lolita the First I was a ridiculous failure. I did my best; I read and

reread a book with the unintentionally biblical title Know Your Own Daughter, which I got at the same store where I bought Lo, for her thirteenth birthday, a de luxe volume with commercially “beautiful” illustrations, of Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. But even at our very best moments, when we sat reading on a rainy day (Lo’s glance skipping from the window to her wrist watch and back again), or had a quiet hearty meal in a crowded diner, or played a childish game of cards, or went shopping, or silently stared, with other motorists and their children, at some smashed, blood-bespattered car with a young woman’s shoe in the ditch (Lo, as we drove on: “that was the exact type of moccasin I was trying to describe to that jerk in the store”); on all those random occasions, I seemed to myself as implausible a father as she seemed to be a daughter. Was, perhaps, guilty locomotion instrumental in vitiating our powers of impersonation? Would improvement be forthcoming with a fixed domicile and a routine schoolgirl’s day?

In my choice of Beardsley I was guided not only by the fact of there

being a comparatively sedate school for girls located there, but also by the presence of the women’s college. In my desire to get myself casè, to

attach myself somehow to some patterned surface which my stripes would blend with, I thought of a man I knew in the department of French at Beardsley College; he was good enough to use my textbook in his classes and had attempted to get me over once to deliver a lecture. I had no intention of doing so, since, as I have once remarked in the course of these confessions, there are few physiques I loathe more than the heavy low-slung pelvis, thick calves and deplorable complexion of the average coed (in whom I see, maybe, the coffin of coarse female flesh within which my nymphets are buried alive); but I did crave for a label, a background, and a simulacrum, and, as presently will become clear, there was a reason, a rather zany reason, why old Gaston Godin’s company would be particularly safe.

Finally, there was the money question. My income was cracking under the strain of our joy-ride. True, I clung to the cheaper motor courts; but every now and then, there would be a loud hotel de luxe, or a pretentious dude ranch, to mutilate our budget; staggering sums, moreover, were expended on sightseeing and Lo’s clothes, and the old Haze bus, although a still vigorous and very devoted machine, necessitated numerous minor and major repairs. In one of our strip maps that has happened to survive among the papers which the authorities have so kindly allowed me to use for the purpose of writing my statement, I find some jottings that help me compute the following. During that extravagant year 1947-1948, August to August, lodgings and food cost us around 5,500 dollars; gas, oil and repairs, 1,234, and various extras almost as much; so that during about 150 days of actual motion (we covered about 27,000 miles!) plus some 200 days of interpolated standstills, this modest rentier spent around 8,000

dollars, or better say 10,000 because, unpractical as I am, I have surely forgotten a number of items.

And so we rolled East, I more devastated than braced with the satisfaction of my passion, and she glowing with health, her bi-iliac garland still as brief as a lad’s, although she had added two inches to her stature and eight pounds to her weight. We had been everywhere. We had really seen nothing. And I catch myself thinking that our long journey had only defiled with a sinuous trail of slime the lovely, trustful, dreamy, enormous country that by then, in retrospect, was no more to us than a collection of dog-eared maps, ruined tour books, old tires, and her sobs in the night–every night, every night–the moment I feigned sleep.

Lane had just shifted his attention from the frogs’ legs to the salad. “Any good?” he said. “What’s it about?”

“I don’t know. It’s peculiar. I mean it’s primarily a religious book. In a way, I suppose you could say it’s terribly fanatical, but in a way it isn’t. I mean it starts out with this peasant—the pilgrim—wanting to find out what it means in the Bible when it says you should pray incessantly. You know. Without stopping. In Thessalonians or someplace. So he starts out walking all over Russia, looking for somebody who can tell him how to pray incessantly. And what you should say if you do.” Franny seemed intensely interested in the way Lane was dismembering his frogs’ legs. Her eyes remained fixed on his plate as she spoke. “All he carries with him is this knapsack filled with bread and salt. Then he meets this person called a starets—some sort of terribly advanced religious person—and the starets tells him about a book called the Philokalia.’ “Which apparently was written by a group of terribly advanced monks who sort of advocated this really incredible method of praying.”

“Hold still,” Lane said to a pair of frogs’ legs.

“Anyway, so the pilgrim learns how to pray the way these very mystical persons say you should—I mean he keeps at it till he’s perfected it and everything. Then he goes on walking all over Russia, meeting all kinds of absolutely marvellous people and telling them how to pray by this incredible method. I mean that’s really the whole book.”

“I hate to mention it, but I’m going to reek of garlic,” Lane said.

“He meets this one married couple, on one of his journeys, that I love more than anybody I ever read about in my entire life,” Franny said. “He’s walking down a road somewhere in the country, with his knapsack on his back, when these two tiny little children run after him, shouting, ‘Dear little beggar! Dear little beggar! You must come home to Mummy. She likes beggars.’ So he goes home with the children, and this really lovely person, the children’s mother, comes out of the house all in a bustle and insists on helping him take off his dirty old boots and giving him a cup of tea. Then the father comes home, and apparently he loves beggars and pilgrims, too, and they all sit down to dinner. And while they’re at dinner, the pilgrim wants to know who all the ladies are that are sitting around the table, and the husband tells him that they’re all servants but that they always sit down to eat with him and his wife because they’re sisters in Christ.” Franny suddenly sat up a trifle straighter in her seat, self-consciously. “I mean I loved the pilgrim wanting to know who all the ladies were.” She watched Lane butter a piece of bread. “Anyway, after that, the pilgrim stays overnight, and he and the husband sit up till late talking about this method of praying without ceasing. The pilgrim tells him how to do it. Then he leaves in the morning and starts out on some more adventures. He meets all kinds of people—I mean that’s the whole book, really—and he tells all of them how to pray by this special way.”

Lane nodded. He cut into his salad with his fork. “I hope to God we get time over the weekend so that you can take a quick look at this goddam paper I told you about,” he said. “I don’t know. I may not do a damn thing with it —I mean try to publish it or what have you— but I’d like you to sort of glance through it while you’re here.”

“I’d love to,” Franny said. She watched him butter another piece of bread. “You might like this book,” she said suddenly. “It’s so simple, I mean.”

“Sounds interesting. You don’t want your butter, do you?”

“No, take it. I can’t lend it to you, because it’s way overdue already, but you could probably get it at the library here. I’m positive you could.”

“You haven’t touched your goddam sandwich,” Lane said suddenly. “You know that?”

Franny looked down at her plate as if it had just been placed before her. “I will in a minute,” she said. She sat still for a moment, holding her cigarette, but without dragging on it, in her left hand, and with her right hand fixed tensely around the base of the glass of milk. “Do you want to hear what the special method of praying was that the starets told him about?” she asked. “It’s really sort of interesting, in a way.”

Lane cut into his last pair of frogs’ legs. He nodded. “Sure,” he said. “Sure.”

“Well, as I said, the pilgrim—this simple peasant—started the whole pilgrimage to find out what it means in the Bible when it says you’re supposed to pray without ceasing. And then he meets this starets—this very advanced religious person I mentioned, the one who’d been studying the ‘Philokalia’ for years and years and years.” Franny stopped suddenly to reflect, to organize. “Well, the starets tells him about the Jesus Prayer first of all. ‘Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.’ I mean that’s what it is. And he explains to him that those are the best words to use when you pray. Especially the word ‘mercy,’ because it’s such a really enormous word and can mean so many things. I mean it doesn’t just have to mean mercy.” Franny paused to reflect again. She was no longer looking at Lane’s plate but over his shoulder. “Anyway,” she went on, “the starets tells the pilgrim that if you keep saying that prayer over and over again—you only have to just do it with your lips at first—then eventually what happens, the prayer becomes self-active. Something happens after a while. I don’t know what, but something happens, and the words get synchronized with the person’s heartbeats, and then you’re actually praying without ceasing. Which has a really tremendous, mystical effect on your whole outlook. I mean that’s the whole point of it, more or less. I mean you do it to purify your whole outlook and get an absolutely new conception of what everything’s about.”

Lane had finished eating. Now, as Franny paused again, he sat back and lit a cigarette and watched her face. She was still looking abstractedly ahead of her, past his shoulder, and seemed scarcely aware of his presence.

“But the thing is, the marvellous thing is, when you first start doing it, you don’t even have to have faith in what you’re doing. I mean even if you’re terribly embarrassed about the whole thing, it’s perfectly all right. I mean you’re not insulting anybody or anything. In other words, nobody asks you to believe a single thing when you first start out. You don’t even have to think about what you’re saying, the starets said. All you have to have in the beginning is quantity. Then, later on, it becomes quality by itself. On its own power or something. He says that any name of God—any name at all—has this peculiar, self- active power of its own, and it starts working after you’ve sort of started it up.”

Lane sat rather slouched in his chair, smoking, his eyes narrowed attentively at Franny’s face. Her face was still pale, but it had been paler at other moments since the two had been in Sickler’s.

“As a matter of fact, that makes absolute sense,” Franny said, “because in the Nembutsu sects of Buddhism, people keep saying ‘Namu Amida Butsu’ over and over again—which means ‘Praises to the Buddha’ or something like that— and the same thing happens. The exact same—”

“Easy. Take it easy,” Lane interrupted. “In the first place, you’re going to burn your fingers any second.”

Franny gave a minimal glance down at her left hand, and dropped the stub of her still-burning cigarette into the ashtray. “The same thing happens in ‘The Cloud of Unknowing,’ too. Just with the word ‘God.’ I mean you just keep saying the word ‘God.’ ” She looked at Lane more directly than she had in several minutes. “I mean the point is did you ever hear anything so fascinating in your life, in a way? I mean it’s so hard to just say it’s absolute coincidence and then just let it go at that—that’s what’s so fascinating to me. At least, that’s what’s so terribly—” She broke off. Lane was shifting restively in his chair, and there was an expression on his face—a matter of raised eyebrows, chiefly— that she knew very well.

“What’s the matter?” she asked.

“You actually believe that stuff, or what?”

Franny reached for the pack of cigarettes and took one out. “I didn’t say I believed it or I didn’t believe it,” she said, and scanned the table for the folder of matches. “I said it was fascinating.” She accepted a light from Lane. “I just think it’s a terribly peculiar coincidence,” she said, exhaling smoke, “that you keep running into that kind of advice— I mean all these really advanced and absolutely unbogus religious persons that keep telling you if you repeat the name of God incessantly, something happens, Even in India. In India, they tell you to meditate on the ‘Om,’ which means the same thing, really, and the exact same result is supposed to happen. So I mean you can’t just rationalize it away without even—”

“What is the result?” Lane said shortly.

“What?”

“I mean what is the result that’s supposed to follow? All this synchronization business and mumbo-jumbo. You get heart trouble? I don’t know if you know it, but you could do yourself, somebody could do himself a great deal of real—”

“You get to see God. Something happens in some absolutely nonphysical part of the heart— where the Hindus say that Atman resides, if you ever took any Religion—and you see God, that’s all.” She flicked her cigarette ash self-consciously, just missing the ashtray. She picked up the ash with her fingers and put it in. “And don’t ask me who or what God is. I mean I don’t even know if He exists. When I was little, I used to think—” She stopped. The waiter had come to take away the dishes and redistribute menus.

“You want some dessert, or coffee?” Lane asked.

“I think I’ll just finish my milk. But you have some,” Franny said. The waiter had just taken away her plate with the untouched chicken sandwich. She didn’t dare to look up at him.

Lane looked at his wristwatch. “God. We don’t have time. We’re lucky if we get to the game on time.” He looked up at the waiter. “Just coffee for me, please.” He watched the waiter leave, then leaned forward, arms on the table, thoroughly relaxed, stomach full, coffee due to arrive momentarily, and said, “Well, it’s interesting, anyway. All that stuff … I don’t think you leave any margin for the most elementary psychology. I mean I think all those religious experiences have a very obvious psychological background—you know what I mean. . . . It’s interesting, though. I mean you can’t deny that.” He looked over at Franny and smiled at her. “Anyway. Just in case I forgot to mention it. I love you. Did I get around to mentioning that?”

“Lane, would you excuse me again for just a second?” Franny said. She had got up before the question was completely out.

Lane got up, too, slowly, looking at her. “You all right?” he asked. “You feel sick again, or what?”

“Just funny. I’ll be right back.”

She walked briskly through the dining room, taking the same route she had taken earlier. But she stopped quite short at the small cocktail bar at the far end of the room. The bartender, who was wiping a sherry glass dry, looked at her. She put her right hand on the bar, then lowered her head—bowed it—and put her left hand to her forehead, just touching it with the fingertips. She weaved a trifle, then fainted, collapsing to the floor.

Hu sends down water from

the sky that fills riverbeds to

overflowing, each according to

its measure. The torrent carries

along swelling foam, akin to

what rises from smelted ore from

which man makes ornaments and

tools. God thus depicts truth and

falsehood. The scum is cast away,

but whatever is of use to man

remains behind. God thus speaks

in parables.

The theme of The Art of the Fugue is composed from elements of two chorales: the Christmas chorale, “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgen- stern” (“How beautifully shines the morning star”) and the second element, from the Easter cantata “Christ lag in Todes- banden” (“Christ Lay in Death’s Bands”). Combined together, it is as if they denote the extremal points of life—birth and death—as if concentrating the entirety of a life into the minute of the theme’s sounding. In each fugue, the theme receives new life, a new form, while preserving unchanged a certain constant essence: It is born and, having sounded, dies, only to be born again in the next fugue. The cycle becomes an expression of the idea of the infinite life of the soul, which is repeatedly born, and continues to exist after death, the expression of which is the theme in inversion. This idea, which was adopted by Pythagoras and Plato, was also interpreted in the works of Leibniz (whom Bach knew personally, and Leibniz’s books were in Bach’s library) : Although Leibniz wrote about the “metamorphoses” of the soul, not about its reincarnations (…) In this context, the gradual increase in complexity of the work with the theme in this cycle, reflects the gradual development and perfection of the soul. Its final stage— the return to its divine source— remains a mystery for humanity: It is at this moment, when the invisible, eternal depths are revealed, that the Final Fugue stops. Therefore, the cycle is deliberately unfinished. It is an expression of those invisible depths, before which man is powerless. There is one additional idea in the theme itself of the Final Fugue. It is symmetrical; it reads the same, backwards and forwards, left to right or right to left.

Its graphic representation (the theme in direct and inverted form) gives mutually reflected pictures of the letters “W” and “M”; “W”=Welt (world), and by the mystical relationship of Russian and German orthography, the same word, in Russian, begins with the letter “M” (mir). You don’t have to be a musician, to see this in the notes. Bach said that only now had he comprehended the internal spirit of music, and that he wanted to investigate it anew. The Art of the Fugue, most likely, is this study. Schumann said of Bach, “he knew a million times more than we can imagine.” “Music is a hidden arithmetic of the unconscious spirit of his counting” Leibniz wrote to the mathematician Goldbach in 1712. Since then, Bach enthusiasts have been striving to decipher these secrets, to uncover a “hidden stream” with the help of “number symbolism”: by counting notes, bars, inserts, sentences, by assigning numbers to notes, etc. The “Bach number” 14 and its inversion 41 play a prominent role, because according to the number alphabet, B+A+C+H = 14 and J+S+B+A+C+H = 41. I looked up Mo, M + O = 28. Twenty-eight is the second perfect number – it’s the sum of its divisors: 1+2+4+7+14. As a perfect number, it is related to the Mersenne prime 7, since 2(3 − 1)(23 − 1) = 28. The next perfect number is 496, the previous being 6.

its been awhile folks