“After 100 years, films should be getting really complicated. The novel has been reborn about 400 times, but it’s like cinema is stuck in the birth canal.”

Exergue

In the year 470 BCE, in the city of Athens, a bustling metropolis nestled on the eastern coast of the Greek mainland, overlooking the Aegean Sea, there lived a group of people who practiced a very secret religion. The city, framed by rolling hills and the rocky heights of the Acropolis, was a hub of philosophy, politics, and art. Yet, beneath its public debates and grand temples dedicated to the Olympian gods, this clandestine group gathered in hidden chambers and sacred groves. Their practices, whispered about in taverns and markets, involved cryptic rituals and teachings passed down only to the initiated. The group claimed to possess knowledge of the divine that transcended the public pantheon, promising insight into the mysteries of existence and the soul’s journey after death.

One of these people was a man named Socrates. He had once served as a soldier in the Peloponnesian War, a brutal and protracted conflict between Athens and Sparta that spanned nearly three decades. The war saw naval battles on the Aegean, sieges of cities, and devastating plagues that ravaged Athens. It was a clash not only of armies but of ideologies—Athens championing democracy and a maritime empire, while Sparta upheld oligarchy and military discipline.

During his service, Socrates distinguished himself for his bravery and endurance, particularly in the battles of Potidaea, Delium, and Amphipolis. Yet, the horrors of war and the decay it wrought upon his beloved city left a lasting impression on him. Returning to Athens, Socrates became increasingly disillusioned with the way of life of the Athenian people. The pursuit of wealth, political power, and fleeting pleasures seemed to him a shallow existence, one that lacked the deeper reflection necessary for a truly virtuous and fulfilling life.

Driven by this growing dissatisfaction, Socrates abandoned the conventional paths of ambition and began dedicating himself to questioning the very foundations of Athenian society. Along with a group of eager followers—young men from prominent families drawn to his wit and intellect—he took to the public spaces of Athens: the agora, shaded porticoes, and even symposia, where Athenians gathered for drinking and discussion. There, Socrates would engage in spirited debates, using his signature method of relentless questioning to expose contradictions and challenge assumptions. His mission was not to teach but to provoke thought, urging those around him to seek truth and wisdom above all else.

His mission was inspired by the masters of that secret sect, such as Parmenides and Empedocles, whose teachings profoundly shaped his thinking. Parmenides, the enigmatic philosopher from Elea, proclaimed that reality was singular, unchanging, and eternal—a realm accessible only through the exercise of pure reason. Empedocles, a mystic and poet, combined philosophical inquiry with esoteric teachings, positing that the cosmos was governed by the interplay of elemental forces and divine cycles of love and strife. Both figures saw reason not merely as a tool for practical understanding but as a sacred path—an instrument through which the human mind could ascend to divine truth.

Socrates took this lineage to heart, believing that reason, along with its allied disciplines—logic, ethics, and dialectic—was not only the highest craft of humanity but also a means of approaching the divine. For Socrates, the meticulous unfolding of thought, the uncovering of contradictions, and the pursuit of wisdom were all acts of reverence. To him, reason was a gift bestowed by the divine, and its proper use ultimately pointed back to its source: the ineffable and eternal presence of God.

The reason we know of Socrates, even after 2,399 years, is because one of his devoted followers, Plato, took it upon himself to preserve his mentor’s legacy. After Socrates’ untimely death—a result of a trial that accused him of corrupting the youth of Athens and introducing new gods—his life and ideas became the subject of profound reflection among those who had been closest to him. Convicted by a narrow margin in a jury of his peers, Socrates faced his sentence with unwavering resolve, choosing death over exile. He drank the hemlock poison in the company of his friends, engaging in philosophical discussion even in his final moments, exploring topics like the immortality of the soul and the nature of death itself.

Following this tragic end, Plato began to collect, from memory and from the accounts of others who had witnessed Socrates’ debates and conversations, the essence of his teachings. These dialogues, often set in the bustling streets of Athens or during intimate gatherings, covered a wide range of topics: the nature of justice, the pursuit of virtue, the foundations of knowledge, and the role of the divine in human life. Plato’s writings immortalized Socrates as a relentless seeker of truth, a man who believed that an unexamined life was not worth living, and who used the power of reason and dialogue to uncover the deeper principles governing existence.

Through these preserved dialogues, Socrates’ ideas have transcended the ages, inspiring countless generations to ask the same enduring questions: What is the good life? How should we live? What does it mean to truly know?

We have all the dialogues. Not one is missing. This astonishing fact has been confirmed through archaeological findings, including ancient receipts and catalogues that document the meticulous preservation and transmission of Plato’s works over centuries. That these dialogues have survived intact, despite the ravages of time, war, and cultural upheaval, is nothing short of miraculous. Across millennia, they have been translated, copied, and transmitted through countless cultures, each leaving its mark on the interpretation of these texts while ensuring their survival for future generations.

In ancient Greece and Rome, scribes and philosophers revered Plato’s dialogues as foundational texts, preserving them in libraries like the famed Library of Alexandria. Even after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, these works found refuge in the Byzantine Empire, where scholars diligently maintained the Greek manuscripts. During the Islamic Golden Age, Plato’s ideas were translated into Arabic, where they influenced Islamic philosophy and were integrated into the works of thinkers like Al-Farabi and Avicenna. These translations would later travel to medieval Europe, where they were reintroduced to the Latin-speaking world during the Renaissance.

The dialogues played a pivotal role in shaping Western civilization. They laid the groundwork for much of Western philosophy, influencing figures from Augustine and Aquinas to Descartes and Kant. Beyond philosophy, the ideas engendered in these dialogues transformed how we think about justice, governance, education, and the nature of reality inspired developments in politics, law, and science. His concept of an ideal republic influenced political theorists from Machiavelli to Rousseau, while his metaphysical explorations informed centuries of theological discourse.

The survival of these dialogues is not merely an academic or historical curiosity. They represent the unbroken transmission of ideas that have continuously challenged, shaped, and expanded the human understanding of ethics, knowledge, and the divine. Without them, the intellectual and cultural foundations of civilization as we know it would be profoundly different, and the legacy of Socrates would likely have been lost to time.

Despite the greatness of this colossal spirit, it should be noted that Socrates was an outcast in his own time. In fact, he was often mocked and ridiculed by his contemporaries, who saw his unconventional methods and probing questions as subversive or even absurd. A notable example of this is the play Clouds by the famous Athenian playwright Aristophanes, first performed in 423 BCE. The play caricatures Socrates as a comical and eccentric sophist, head of a “Thinkery” where absurd ideas are taught, such as how to use rhetoric to evade debts or justify immoral behavior. Aristophanes portrays Socrates as a man detached from practical realities, preoccupied with nonsensical theories about the heavens and the earth, floating in a basket to better contemplate the cosmos.

The mockery in Clouds was not merely comedic but deeply biting, contributing to the public perception of Socrates as a dangerous influence on Athenian youth. This portrayal arguably played a role in shaping the cultural atmosphere that later led to his trial and execution. Socrates himself referenced the play during his trial, acknowledging its impact on how he was perceived by the jury and the wider public.

There is a story—though its authenticity is debated—that Plato, Socrates’ most devoted student, kept a copy of Clouds under his pillow at night. Whether out of a desire to understand the mindset of his teacher’s critics or as a reminder of the societal challenges Socrates faced, the tale sheds light on Plato’s approach to his writing. Plato may have chosen the dialogue form not only to honor the conversational style of his master but also as a subtle response to Aristophanes. By presenting Socrates in a series of profound and reasoned debates, Plato countered the caricature from Clouds, offering a lasting and dignified image of his mentor to history.

Additionally, in some of his works—most notably the Symposium—Plato does not shy away from including Aristophanes as a character, but he does so in a way that subtly undercuts the playwright. In the Symposium, Aristophanes is given a humorous and memorable speech about love, but his hiccups and comedic tone serve to highlight the intellectual depth of Socrates by contrast. It is tempting to see this as Plato’s way of settling the score, turning Aristophanes into a literary foil and asserting the superiority of his master’s wisdom over the shallow mockery of the stage.

We are coming closer to the topic of this essay. In one of the dialogues—The Republic, one of Plato’s most celebrated works and universally recognized as a cornerstone of philosophical thought—Socrates delves into profound discussions about justice, the ideal society, and the nature of reality itself. The Republic has become a timeless text studied across cultures and disciplines, influencing philosophy, political theory, education, and even psychology. Its themes transcend historical context, offering insights that remain relevant to the modern world.

The dialogue is set during a gathering at the home of Cephalus, a wealthy and elderly Athenian, and unfolds in a conversational setting that includes several key figures: Polemarchus, Cephalus’s son; Thrasymachus, a fiery sophist; and Glaucon and Adeimantus, Socrates’ close companions and Plato’s own brothers. Through their exchanges, Socrates examines and challenges their views on justice, power, morality, and the structure of an ideal society.

Socrates never shies from employing from the sum of his memory all branches of knowing, from ethics, politics, metaphysics, poetry, and mathematics in order to deliver, like a midwife, an Idea. Guiding his interlocutors not by denying different opinions or forcing answers but by helping them bring forth their own understanding. At the heart of his teaching lies the conviction that ideas, like truths, must be uncovered and birthed through rigorous examination and dialectic. An allegory is told, an allegory about a cave. Socrates asks his companions to imagine prisoners chained inside a dark cave, their entire reality limited to shadows projected on a wall by objects moving before a fire behind them. For these prisoners, the shadows are the only truth they know.

Without delving into the meaning or symbolism of this allegory, nor the reasons and motivations behind Plato’s unique arrangement and recollection of these dialogues (as explored, for example, in Derrida’s essay Plato’s Pharmacy), I would like to pause here and begin toward the topic of this essay. The allegory of the cave, and particularly the wall of shadows within it, serves as one of the earliest and most poignant examples of a phenomenon that has come to define the life of every human being in the modern world: screens.

The cave wall, onto which shadows are projected, is more than a metaphor for ignorance or limited perception—it is an eerily prescient precursor to a surface that pervades our lives today. We are immersed in a world mediated by screens: televisions, smartphones, computers, screens that manifest images, stories, and information that have the power to transform our perceptions, beliefs, and identities.

This tension between appearance and reality, between the mediated and the actual, not only serves as a microcosm of the theater but also encapsulates its profound symbolic significance. The theater, as an ancient art form, has always operated as a space of mediated reality—a place where illusion and representation create a world that is not real yet powerfully affects those who witness it. In the theater, the audience willingly suspends disbelief, engaging with shadows of reality that evoke emotion, provoke thought, and reveal truths hidden in the everyday. This act of mediation, where representation becomes a tool for exploring the human condition, mirrors the dynamic of Plato’s cave and prefigures the role of screens in modern life.

Beyond the theater, this tension has come to define what the French theorist Guy Debord famously termed the Spectacle. In his influential work The Society of the Spectacle, Debord describes the Spectacle as a pervasive system of images, representations, and commodities that mediates all aspects of human life. The Spectacle, he argues, is not merely a collection of media or entertainment; it is a social relationship mediated by images. In this sense, the Spectacle transforms reality into a mere representation, replacing direct human experiences with mediated ones. It turns individuals into passive spectators, consuming images that shape their desires, beliefs, and perceptions of the world.

The allegory of the cave finds new resonance in Debord’s critique. Just as the prisoners in the cave mistake shadows for reality, modern individuals are often ensnared by the images of the Spectacle, mistaking mediated representations for authentic experiences. Screens—whether televisions, smartphones, or digital displays—have become the new walls of the cave, projecting images that inform, entertain, and manipulate. They amplify the human condition, offering unprecedented access to information and connection, while simultaneously distancing us from the unmediated presence of reality.

Reflecting on the profound resonance between the shadows of the cave and the images on our screens, we uncover deeper implications of living in this mediated reality. Between presence and absence, reality and representation, lies a fragile boundary that screens constantly negotiate. Indirect representation, as Plato’s allegory warns, can serve as both an illuminating guide and a distorting veil. On one hand, it offers pathways to knowledge, connecting us to ideas and people across vast distances. On the other, it risks alienating us from the immediacy of truth, replacing direct experience with curated fragments of reality.

This risk, for Plato’s Socrates, cannot be understated, as it is not merely a handicap or an obstacle to understanding—it is a profound and existential danger, perhaps the greatest danger humanity faces. For Socrates, the journey of philosophy, of questioning and seeking truth, is ultimately a spiritual endeavor, a means of aligning the soul with the divine. To be deceived by appearances, to mistake shadows for reality, is to turn away from the light of truth and thereby sever our communion with God—the ultimate source of goodness, beauty, and knowledge. To live in ignorance of this reality is not simply to misunderstand the world—it is to live a life alienated from the divine order, a life disconnected from the true purpose of the soul.

It is not just a question of failing to achieve knowledge or wisdom; it is a spiritual failure, a disconnection from the highest good and the divine source of being. This disconnection, perpetuated by the pervasive influence of mediated realities, threatens not only individuals but entire societies, as it fosters a culture of superficiality, distraction, and moral disengagement. The failure of this endeavor—the soul’s resignation to shadows and appearances—represents the ultimate forfeiture of human existence’s true purpose: to seek the Good, to align with the divine, and to live a life grounded in virtue and understanding.

Art, religion, and philosophy: this triptych forms one of the central pillars of The Phenomenology of Spirit and Lectures on Aesthetics by the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Hegel, a towering figure of German Idealism, wrote during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a period marked by profound political, intellectual, and cultural upheaval. His philosophy sought to synthesize the ideas of his predecessors—particularly Kant, Fichte, and Schelling—into a comprehensive system that explained the development of human consciousness, history, and the nature of reality itself.

Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) explores the evolution of human consciousness as it progresses through various stages, from sense perception to self-awareness, and ultimately to absolute knowledge, where the individual recognizes its unity with the universal. This work was written against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars and the sweeping societal transformations of Enlightenment rationalism and Romanticism. It reflects Hegel’s belief that history is a rational process, moving toward the realization of freedom and the unfolding of the Absolute Spirit.

Later, in his Lectures on Aesthetics, Hegel delves into art, religion, and philosophy as key modes through which the human spirit expresses and apprehends truth. These lectures, delivered in the 1820s, were part of Hegel’s broader exploration of how the Absolute—the ultimate reality or universal spirit—manifests in human experience. While art reveals truth in sensory forms, religion conveys it symbolically, and philosophy articulates it conceptually and systematically.

Hegel’s triptych illustrates his conviction that human history and culture are not chaotic or arbitrary but part of a grand, dialectical process. This process unfolds as spirit (or mind) seeks to understand and realize itself fully, advancing through these stages of expression. His work profoundly influenced disciplines as diverse as philosophy, theology, art theory, and political thought, leaving a legacy that continues to shape contemporary debates about reason, freedom, and the nature of human existence.

Here we are at last, arriving at the spirit of this exergue, weaving through the lattice of these themes to unveil the fruition of the human spirit through the convergence of three profound disciplines: art, religion, and philosophy. Together, they herald the emergence of a technology that has yet to fully reveal its true essence.

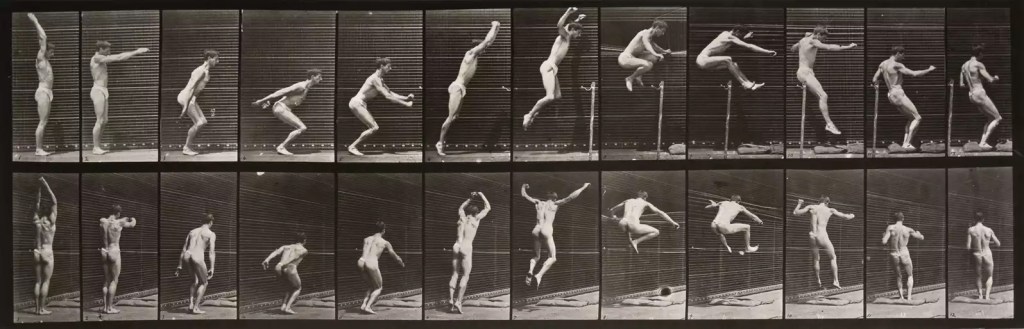

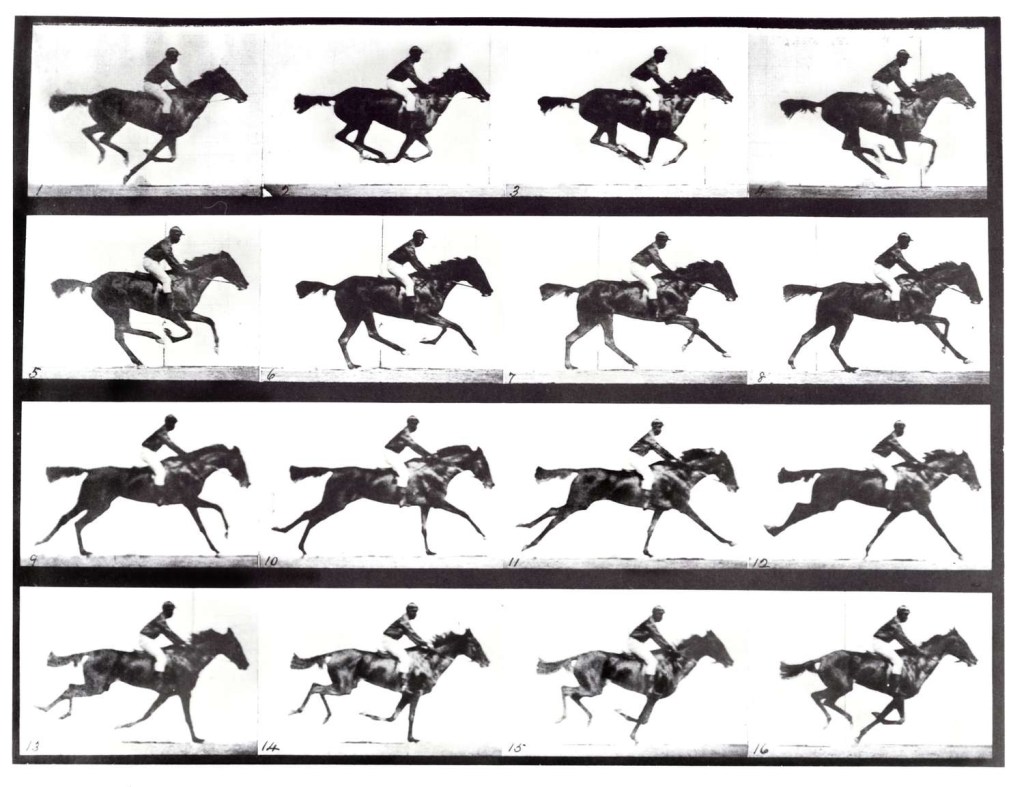

Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904), born Edward James Muggeridge in England, was a pioneering photographer and inventor who revolutionized the study of motion. After moving to the United States, he became known for his stunning landscape photography, especially of Yosemite. In 1872, he was hired by Leland Stanford to resolve whether a horse’s hooves leave the ground while galloping. Muybridge’s use of sequential photography proved they did, marking a breakthrough in motion studies. His invention of the zoopraxiscope—a precursor to the motion picture projector—laid the foundation for cinema. Muybridge later expanded his work to study human and animal movement, publishing the influential Animal Locomotion (1887).

Science and Art

Muybridge bridged art and science by using photography to analyze motion with unprecedented precision. His images, blending aesthetic composition with empirical observation, provided invaluable insights for biomechanics, physiology, and visual storytelling. Artists like Marcel Duchamp and movements such as Cubism and Futurism drew inspiration from his fragmented depictions of motion, while scientists used his studies to understand locomotion. His work demonstrated that photography could serve as both a creative and scientific tool, transforming static images into dynamic sequences that revealed the mechanics of life.

In cinema, Muybridge’s sequential photography became the basis for creating the illusion of motion, influencing inventors like Thomas Edison and filmmakers like the Lumière brothers. His deconstruction of motion into frames allowed cinema to manipulate time and space, turning movement into a narrative and artistic medium.

Philosophy

Muybridge’s work posed profound questions about time, perception, and reality. By breaking motion into individual frames, he challenged the classical idea of time as continuous, suggesting instead that it is composed of discrete moments. This fragmented view influenced thinkers like Henri Bergson, who debated the tension between mechanical time and lived experience.

His work also revealed the limits of human perception. Movements too fast for the naked eye became visible through technology, raising questions about the reliability of sensory experience and the role of machines in shaping reality. Additionally, his images suggested that motion itself might be an illusion—a construct of the brain interpreting sequential stills, a concept foundational to cinema.

Muybridge’s motion studies not only transformed photography and film but also redefined how we perceive the world, blending art, science, and philosophy into a unified exploration of life in motion.

Silent Cinema

Silent cinema owes an immense debt to Eadweard Muybridge, whose pioneering work laid the conceptual, technical, and artistic foundation for the medium. While the Lumière brothers, Georges Méliès, and Thomas Edison are often credited as the early architects of film, it was Muybridge who first demonstrated that motion could be captured, analyzed, and reconstructed for audiences—a principle at the heart of cinema. Silent film’s reliance on visual storytelling, sequential action, and technical innovation can all be traced back to Muybridge’s groundbreaking experiments.

1. The Foundations of Motion Pictures

At its core, silent cinema relies on the illusion of movement created by showing a series of still images in rapid succession. Muybridge’s 1878 experiment, The Horse in Motion, was the first systematic effort to dissect and recreate motion using photography. He placed 12 cameras along a racetrack, capturing each phase of a horse’s gallop, proving that motion could be broken into discrete moments and reassembled visually. This principle—motion as sequential stills—forms the backbone of cinema. Without Muybridge’s technical and conceptual breakthroughs, the notion of “moving pictures” may not have emerged.

By tracing this path from Muybridge’s scientific motion studies, through Lang’s sociological depth, to Disney’s imaginative artistry, we see how cinema evolved into a tool not just for representing reality, but for reimagining it, engaging audiences on intellectual, emotional, and moral levels.

2. The Zoopraxiscope: Precursor to Silent Projection

Muybridge’s invention of the zoopraxiscope in 1879 created the first cinematic experience. Using painted discs of his photographic sequences, he projected animated motion onto a screen for live audiences, effectively merging science with entertainment. Silent cinema owes its very format to this moment, as the zoopraxiscope transformed motion studies from private, scientific observations into public, shared experiences.

Muybridge’s traveling lectures, which featured his projected motion studies, prefigured the silent film screenings of the 1890s and early 20th century. His demonstrations not only entertained but also educated audiences, much like early silent films that combined spectacle with storytelling.

3. Visual Storytelling Without Sound

Silent cinema depends entirely on visual storytelling, using movement, expression, and composition to convey meaning. Muybridge’s work pioneered this form of communication by presenting narrative and action purely through motion. His studies of human and animal locomotion, such as people running, leaping, or performing everyday tasks, offered a visual lexicon of action that filmmakers later drew upon.

For example:

Filmmakers like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton relied on nuanced physicality and dynamic movement to create comedic and dramatic tension, echoing Muybridge’s detailed motion studies.

The concept of sequential action in silent film mirrors Muybridge’s framing, where each still tells a part of a broader story.

4. Technical Innovations and Film Equipment

Silent cinema’s technical achievements, including the kinetoscope, cinematograph, and early cameras, were heavily influenced by Muybridge’s methods. His experiments inspired inventors like Étienne-Jules Marey, who refined motion photography, and Thomas Edison, who built the kinetoscope. Muybridge’s trip-wire system for triggering cameras and his fast shutter speeds provided a technical framework for capturing motion, which inventors adapted for moving film reels.

Silent cinema, as an industry, stands on the shoulders of Muybridge’s ability to perfect the mechanical processes required to record motion. Early filmmakers refined what Muybridge had already proven: that still images, when captured sequentially and played back quickly, could produce the illusion of life.

5. Philosophical and Aesthetic Influence

Muybridge’s work had a profound influence on the aesthetic and philosophical underpinnings of silent cinema:

Fragmented Time: Silent films, especially those experimenting with editing, owe their conception of time to Muybridge. His frame-by-frame breakdown of motion mirrored the way filmmakers like D.W. Griffith or Sergei Eisenstein cut and reassembled scenes to manipulate the viewer’s sense of time and space.

Human and Animal Locomotion: Muybridge’s detailed studies of movement provided a reference for animators, directors, and cinematographers, enabling them to recreate realistic or exaggerated motion on screen. His sequences of galloping horses, running athletes, and dancing figures remain iconic visual templates for depicting kinetic energy.

Representation of Reality: Muybridge’s work suggested that motion could be both a scientific and artistic construct, a concept that silent films explored. Filmmakers like Georges Méliès, who blended reality with fantasy, owe their imaginative use of cinema to Muybridge’s early demonstrations that motion itself could be shaped and manipulated.

6. The Human Body in Silent Cinema

Much of silent film focused on the human body—its movements, gestures, and interactions. Muybridge’s studies of human locomotion (e.g., walking, running, jumping) served as a vital reference for actors and directors. His work cataloged the possibilities of human motion, enabling filmmakers to craft believable characters and physical performances.

Silent cinema owes its origins to Eadweard Muybridge, whose work not only provided the technical and conceptual basis for moving images but also shaped the language of visual storytelling. His motion studies bridged art, science, and entertainment, laying the foundation for a medium that would evolve into the most influential form of communication in the modern era. Muybridge was the first to show that movement could be captured, reconstructed, and shared—a debt the silent film era repaid by turning his experiments into a global art form. Without Muybridge, there would be no cinema.

The Metaphysics and Phenomenology of Photography: Light, Time, and Muybridge’s Gaze

Photography, derived from the Greek words phos (light) and graphé (writing), is the art and science of writing with light. It transforms fleeting moments into lasting images, raising profound questions about reality, perception, and representation. Beyond its technical origins, photography is deeply philosophical, engaging with the metaphysics of time, the phenomenology of perception, and the power dynamics inherent in the act of looking—the gaze. Eadweard Muybridge’s pioneering motion studies, which used sequential photography to analyze movement, are a crucial touchstone for exploring these ideas. His work invites us to consider the ways photography shapes how we see and interpret reality, how it mediates power through the gaze, and how it reveals truths hidden in the flow of time.

Photography as Light Writing and the Gaze

The term photography emphasizes its fundamental connection to light, yet it also implicates the act of looking—the gaze. When light reflects off a subject, it is captured by the camera, either on film or through a digital sensor. In traditional photography, silver halide crystals darken when exposed to light, creating a chemical imprint of the scene. In digital photography, photons are converted into electrical signals, which are processed into an image. Whether analog or digital, photography freezes light and gaze into an artifact, preserving the act of looking as much as the subject itself.

This fusion of light and gaze gives photography its philosophical power. The camera is not a passive recorder of reality but an active participant, framing and isolating what is seen. It chooses what to illuminate and what to obscure, directing the viewer’s gaze and shaping how the subject is perceived. Muybridge’s work exemplifies this dynamic. His motion studies, such as The Horse in Motion (1878), dissected continuous movement into discrete frames, transforming an ephemeral phenomenon into a series of moments. The camera’s gaze, operating with mechanical precision, revealed truths beyond the reach of the human eye, demonstrating photography’s capacity to mediate and direct perception.

The Metaphysics of Time and the Gaze

Photography’s most profound metaphysical implication lies in its ability to arrest time. Time, as we typically experience it, flows as a continuous stream, yet photography interrupts this flow, freezing it into discrete fragments. This act of temporal dissection raises enduring philosophical questions about the nature of time, existence, and the power dynamics of the gaze. Is reality an unbroken continuum, as Henri Bergson described in his concept of duration, or can it be divided into measurable, discrete moments, as suggested by the scientific and photographic tools that Eadweard Muybridge pioneered?

Bergson’s notion of time as duration—a qualitative, indivisible flow of lived experience—stands in tension with Einstein’s relativity, which treats time as a quantifiable dimension governed by measurable intervals and the speed of light. Bergson argued that reducing time to mathematical constructs, such as those captured by Muybridge’s sequential photography, fails to capture its dynamic, subjective essence. Muybridge’s dissection of motion into individual photographic frames aligns more closely with Einstein’s perspective, visualizing time as measurable and divisible. Yet it also exposes the limitations of this reduction, as the fluidity of motion and the lived experience of time resist full containment within discrete, static images.

This tension gains additional depth when set against Immanuel Kant’s conception of time as a pure form of intuition, an a priori framework through which human beings structure all experience. For Kant, time is not something external that flows or can be divided but rather a necessary condition of perception itself. Muybridge’s experiments visually materialize time as both a structured framework (echoing Kant’s notion of intuitive order) and as a dissected series of measurable instants (aligning with Einstein). At the same time, Muybridge’s fragmented frames compel the viewer to engage with the idea of Bergsonian duration, as their gaze reconstructs the movement between frames, grasping for the ineffable continuity of time.

The gaze itself becomes central to this philosophical inquiry. Photography, by directing and fixing the gaze, alters our relationship with time and reality. Muybridge’s work amplifies the power dynamics of the gaze: his camera observes and fragments movement, turning subjects—be they human or animal—into objects of analysis. This act of looking is not neutral. It asserts control over the flow of time, reshaping it into something observable and comprehensible to an external viewer. The gaze of Muybridge’s camera, much like the viewer’s gaze upon his work, embodies both an epistemic ambition to know and a metaphysical confrontation with time’s resistance to full capture.

Muybridge’s motion studies, therefore, are far more than technological feats; they are philosophical provocations. By arresting motion and dissecting time, his work challenges us to consider whether time is an indivisible whole, a sequence of quantifiable moments, or a necessary condition of perception. In doing so, Muybridge also reveals the intricate interplay between time and the gaze: how the act of looking, whether through a camera lens or in the contemplation of his images, mediates our understanding of reality. At this intersection of Bergson’s metaphysics, Einstein’s physics, Kant’s idealism, and the dynamics of the gaze, Muybridge’s legacy invites us to confront the profound mysteries of time, existence, and perception.

Through the camera’s gaze, Muybridge also transforms time into an object of scrutiny. Each frame in his motion studies is a fixed point in the flow of existence, preserved for analysis. This preservation of time invites reflection on the transient nature of being. Photography, as Roland Barthes argued, is always tied to the “that-has-been,” simultaneously affirming presence and absence. Muybridge’s photographs, while scientific in purpose, resonate with this metaphysical tension, making visible the impermanence of motion and the inevitability of change.

Phenomenology and the Gaze: How We See

From a phenomenological perspective, photography mediates how we experience and perceive the world, shaping our engagement with reality through the processes of intentionality and reduction. Intentionality—the directedness of consciousness toward an object—is inherent in the act of photography, as both the photographer and the viewer engage with the subject through the frame. By choosing what to capture and how to present it, photography directs our attention and creates a particular meaning for the image.

The photographic act can also be likened to the phenomenological processes of bracketing and epoché, where preconceptions about the world are set aside to focus on the essence of an experience. In photography, the camera isolates its subject from its broader context, creating a form of reduction that emphasizes certain elements while excluding others. This selective framing encourages viewers to engage with the image on its own terms, prompting a fresh encounter with the phenomena presented. In this way, photography transcends mere documentation, becoming a medium that redefines our understanding of reality by suspending assumptions and revealing the world in new ways.

Muybridge’s motion studies complicate this phenomenological dynamic by fragmenting motion into static images. The gaze of the camera isolates moments that the human eye perceives as continuous, revealing patterns and structures that were previously invisible. For instance, his studies of human and animal locomotion reveal the mechanics of movement, challenging viewers to reconstruct the flow of motion mentally. This interplay between the visible and the imagined highlights photography’s dual role as both a record of reality and a stimulus for subjective interpretation.

Moreover, the gaze in Muybridge’s work is not neutral. It is a gaze of control and analysis, dissecting its subjects with scientific precision. This gaze reflects the broader power dynamics of photography, which often transforms its subjects into objects of study. Muybridge’s motion studies exemplify this power dynamic, turning humans and animals into data to be cataloged and understood. This dynamic raises ethical questions about the relationship between the photographer, the subject, and the viewer.

Muybridge’s Gaze as a Philosophical Inquiry

Muybridge’s work demonstrates how the gaze of the camera can transcend its technical function to become a tool for philosophical inquiry. By directing the gaze toward motion, Muybridge revealed truths that lay hidden in the flow of time. His motion studies, such as his depictions of a galloping horse or a man walking, not only resolved scientific questions but also illuminated the structures of reality that lie beyond human perception.

This philosophical gaze extends beyond the individual frames of Muybridge’s work. By dissecting motion, Muybridge challenged viewers to reconsider their understanding of time, space, and existence. His photographs, while seemingly mechanical, are deeply metaphysical, capturing the essence of movement and revealing the complexity of being.

The Gaze and Sociology: Public Engagement

Muybridge’s use of the gaze was not confined to scientific exploration; it also had profound sociological implications. By exhibiting his motion studies to the public, Muybridge made abstract scientific concepts accessible to a wide audience. His work demonstrated how photography could bridge the gap between academic knowledge and public understanding, using the gaze of the camera to illuminate hidden truths.

This sociological gaze finds echoes in contemporary uses of photography and visual media, particularly in their ability to engage with questions of human behavior and societal dynamics. Through its ability to frame and dissect reality, photography extends Muybridge’s legacy by transforming motion and behavior into subjects of scrutiny. His analytical gaze, which deconstructed motion into observable sequences, laid the groundwork for visual explorations of criminology, sociology, and morality, enabling deeper understandings of how individual actions intersect with larger societal structures.

Photography, as an act of light writing and directed gaze, is both a technical and philosophical practice. It engages with profound metaphysical questions about time, existence, and representation, while also shaping how we perceive and understand the world. Muybridge’s motion studies exemplify photography’s power to transform the ephemeral into the eternal, using the gaze of the camera to reveal truths hidden in the flow of time.

Through his pioneering work, Muybridge demonstrated that photography is not merely a mechanical process but a deeply philosophical one, capable of illuminating the nature of reality and mediating human understanding. His legacy endures as a testament to the transformative power of the photographic gaze, inviting us to reflect on the complexities of time, perception, and being.

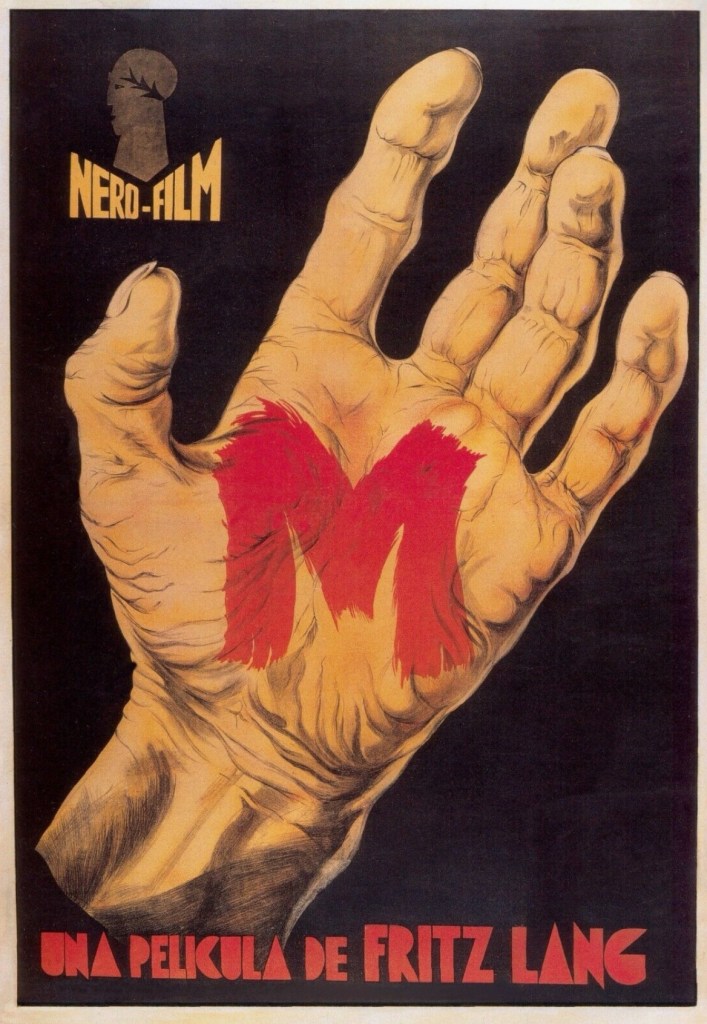

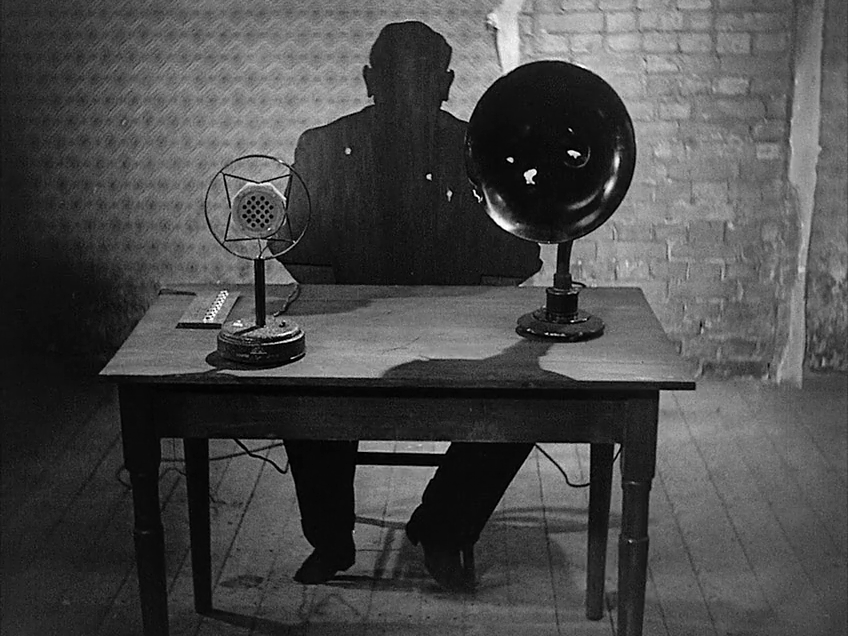

Fritz Lang’s M (1931) represents a culmination of ideas and techniques that can be traced back to Eadweard Muybridge’s groundbreaking work. Although M is a sound film, its visual storytelling, use of motion, and philosophical exploration of human behavior owe a significant debt to the innovations that began with Muybridge. Lang’s mastery of cinematic language builds upon Muybridge’s foundational ideas about motion, perception, and the fragmented representation of time.

1. Visual Storytelling and the Language of Motion

Muybridge’s motion studies laid the foundation for visual narratives in cinema, particularly during the silent and early sound eras. In M, Fritz Lang integrates motion as a vital storytelling element. The hunted killer, played by Peter Lorre, is defined by his nervous, erratic movements, which vividly express his psychological torment. This use of physical motion as a narrative tool reflects Muybridge’s exploration of the expressiveness inherent in human locomotion. Additionally, Lang’s meticulous framing and sequencing of movement, exemplified in the tense pursuit of Lorre’s character through narrow streets, parallels Muybridge’s sequential photography. Each action unfolds methodically, step by step, amplifying tension and drawing the audience into the drama of the chase.

2. Philosophical Ties: Observation and Human Nature

Muybridge’s motion studies introduced the concept that movement could be dissected and analyzed to reveal deeper insights into behavior. Similarly, Fritz Lang’s M employs cinematic techniques to examine human nature and the complex relationship between the individual and society. Just as Muybridge used photography to capture hidden details of motion, Lang utilizes the camera to observe the city and its inhabitants with forensic precision. The pervasive theme of surveillance in M—conducted by both the police and the criminal underworld—echoes Muybridge’s idea that technology can uncover truths invisible to the naked eye. Furthermore, Muybridge’s sequential breakdown of motion finds a parallel in Lang’s fragmented portrayal of the city. The film cuts between disjointed scenes, shifting perspectives, and fleeting actions to construct a chilling depiction of a society on edge. This fragmentation mirrors the fractured morality and psychology of the characters, emphasizing the disconnection and unease within the world of the film.

3. Technical Innovations and Influence

Fritz Lang’s M expands on the technical innovations pioneered by Muybridge. Muybridge’s sequential photographs laid the groundwork for modern editing, demonstrating how individual frames, when viewed in sequence, could create meaning. Lang’s editing style, particularly during the intense manhunt scenes, draws on this legacy by meticulously assembling fragmented actions to build suspense. Similarly, Muybridge’s studies of human and animal motion introduced a new level of realism to visual representation. Lang adopts this principle by capturing the nuanced, naturalistic movements of his characters, from the hunted killer to the frenzied crowds pursuing him. This attention to realistic motion deepens the film’s psychological complexity and reinforces its grounding in reality.

4. Thematic Connections: Time, Movement, and Morality

Muybridge’s work transformed perceptions of motion and time, a legacy that Fritz Lang builds upon in M to explore profound thematic concerns. Just as Muybridge’s studies fragmented time into measurable moments, Lang portrays it as fractured and relentless, with the ticking clock and rhythmic movements of the city underscoring the inevitability of justice—or vengeance—closing in on the killer. Muybridge’s exploration of the inevitability of motion, where each frame logically follows the next, finds a philosophical parallel in Lang’s narrative. Human actions, once initiated, are portrayed as inescapable, leading inexorably to their consequences. This interplay of time, motion, and inevitability forms a central axis of M’s storytelling.

Fritz Lang’s M embodies the legacy of Eadweard Muybridge’s contributions to cinema. From its reliance on motion to its exploration of surveillance, fragmentation, and time, M exemplifies the evolution of Muybridge’s ideas into a sophisticated cinematic language. Lang’s work not only builds on Muybridge’s technical and conceptual innovations but also deepens them, using motion and visual storytelling to probe the complexities of human behavior and morality. In this way, M serves as both a masterpiece of cinema and a testament to the enduring influence of Muybridge’s pioneering work.

Criminology

Eadweard Muybridge’s innovations in motion photography not only laid the technical groundwork for cinema but also established a new way of studying and presenting human behavior. By dissecting motion into discrete, observable moments, Muybridge demonstrated how technology could expose truths hidden to the naked eye, a revelation that would prove invaluable to sociological and criminological inquiry. Fritz Lang’s M (1931) takes these foundational principles and extends them into the realm of social commentary, using the medium of cinema to explore crime, morality, and societal dynamics in ways that Muybridge’s work made possible.

Muybridge’s Innovations and Sociological Implications

Muybridge’s groundbreaking photographic studies, such as Animal Locomotion, systematically analyzed human and animal behavior, transforming abstract movement into observable patterns. By dissecting motion, Muybridge not only advanced fields like biomechanics and psychology but also hinted at broader sociological applications, suggesting that movement could reveal truths about human intent, habit, and emotion. This principle aligns with criminology’s focus on behavior as something that can be observed, analyzed, and dissected to uncover patterns and motivations—a concept Fritz Lang fully explores in M.

Muybridge also introduced the idea of technology as an observer, demonstrating through his experiments that photography could reveal details invisible to the human eye. This concept finds a direct parallel in Lang’s M, where the camera becomes a tool for surveillance and control. Technology is used to track the criminal, played by Peter Lorre, capturing his movements and behavior with meticulous precision. Through this interplay of observation and technology, both Muybridge and Lang reveal the power of the mechanical eye to uncover hidden truths.

Lang’s M: Sociological Exploration Through Cinema

Building on Muybridge’s technical and philosophical framework, Fritz Lang uses the cinematic medium in M to explore criminology and sociology on a public scale. Lang transforms Muybridge’s method of capturing hidden details into a narrative device, using observation and surveillance as central themes. In M, the killer is constantly under watch—not only by the police but also by the criminal underworld and society at large. The camera acts as an impartial observer, echoing Muybridge’s photographic detachment, recording movement and behavior that expose the psychology of both the criminal and those pursuing him. By illustrating how technological observation uncovers the killer’s patterns and movements, Lang highlights the role of surveillance in criminology as a means to understand and predict human behavior.

Lang also draws on Muybridge’s sequential breakdown of motion to depict fragmented narratives and actions in M. The film intercuts between seemingly disconnected sequences—the killer’s aimless wandering, police investigations, and the criminal underworld’s plotting—mirroring Muybridge’s analytical dissection of motion. This fragmented approach portrays crime not as an isolated act but as part of a larger societal network. The disjointed yet interconnected sequences reflect the complexities of human behavior and society’s collective reaction to deviance, creating a sociological map of cause and effect.

Much like Muybridge’s public exhibitions, which made complex ideas about motion accessible to broader audiences, Lang uses M to present criminological theories and societal dilemmas in a visual, relatable format. The film delves into the psychological motivations of a child murderer, inviting viewers to grapple with emerging ideas in criminal psychology and the moral tensions surrounding justice and societal responsibility. The climactic trial, where the killer pleads for understanding rather than condemnation, challenges audiences to consider the root causes of crime—mental illness, societal neglect, or inherent evil—turning the film into a public forum for sociological reflection and debate.

Muybridge’s Legacy in Lang’s Sociological Cinema

Muybridge’s approach to motion studies, which treated human and animal movement as data to be cataloged and analyzed, finds a profound echo in Fritz Lang’s M. In the film, Lang applies this principle by treating the killer’s actions and society’s response as observable patterns, revealing underlying structures of law, morality, and collective fear. Just as Muybridge’s photographic tools uncovered hidden truths about movement, Lang uses the camera to delve into the psychological and societal dimensions of crime. Through a focus on surveillance—both visual, as the killer is tracked, and auditory, with the whistle tune that identifies him—Lang extends Muybridge’s legacy into criminology, demonstrating how technology aids in understanding human behavior.

Much like Muybridge’s motion studies, which engaged the public with groundbreaking visual insights, Lang’s M uses cinema to present sociological concepts to a broad audience. The film challenges viewers to confront questions of guilt, justice, and societal complicity, transforming its narrative into a public forum for reflection on crime and its broader implications.

Muybridge’s work transformed the study of motion into a scientific and artistic pursuit, introducing methods of observation and analysis that Fritz Lang would adapt to explore crime and society in M. By applying Muybridge’s techniques of fragmentation, observation, and public presentation, Lang extends these innovations to address sociological questions, using cinema to expose the complexities of criminology and societal behavior. Muybridge opened the door to understanding human actions in measurable terms, and Lang used that foundation to explore the human condition, presenting these ideas to audiences in a powerful, accessible medium. Together, they represent a continuum of innovation that shaped cinema as both art and social commentary.

Dr. Mabuse and M: A Comparative Exploration of Power, Crime, and Society

Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922) and M (1931) are seminal works in the history of cinema, each a masterful exploration of power, crime, and the fragile structures of society. While the films differ in tone, narrative, and historical context, they complement each other by presenting two sides of Lang’s overarching fascination with the interplay between individuals and social systems. Dr. Mabuse portrays the destructive potential of a master manipulator operating outside moral constraints, while M offers a more intimate and psychological view of crime, focusing on a society’s collective struggle to confront and comprehend deviant behavior. Together, these films reveal Lang’s ability to dissect the anxieties of his era and provide an enduring commentary on power, fear, and the human condition.

The Plot of Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler

Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler introduces the titular character as a criminal mastermind who uses hypnosis, psychological manipulation, and elaborate schemes to control others and amass wealth and influence. Mabuse, portrayed with chilling precision by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, is a shadowy figure who operates in the underbelly of Weimar-era Berlin. The film is structured as a sprawling two-part epic. In the first part, “The Great Gambler: A Picture of the Time,” Mabuse’s schemes are revealed as he manipulates stock markets, gamblers, and political figures, destabilizing the fragile social order. The second part, “Inferno: A Game for the People of Our Age,” sees Mabuse’s criminal empire begin to crumble as he is pursued by State Prosecutor von Wenk.

The film’s narrative oscillates between scenes of chaos and control, with Mabuse embodying unchecked power and societal corruption. As his schemes unravel, Mabuse descends into madness, ending the film imprisoned, scribbling cryptic symbols in his cell—a powerful image of the self-destructive nature of absolute power.

The Plot of M

Nine years later, Lang released M, a tightly focused and psychologically rich examination of a society in turmoil. The film follows Hans Beckert, a child murderer played hauntingly by Peter Lorre, as he evades capture in a city gripped by fear and paranoia. Unlike the expansive scope of Dr. Mabuse, M concentrates on the collective response to Beckert’s crimes. The police intensify their surveillance efforts, while the criminal underworld organizes its own manhunt, frustrated by the increased police presence disrupting their activities.

Beckert is eventually captured by the criminals and brought to an underground trial, where he pleads for his life, claiming he cannot control his impulses. The film ends ambiguously, with Beckert’s fate left unresolved, emphasizing themes of justice, morality, and the limits of human understanding.

Complementary Themes: Power, Crime, and Society

Despite their differences in scale and tone, Dr. Mabuse and M are deeply interconnected through their exploration of power, crime, and societal response. Mabuse and Beckert are contrasting embodiments of deviance: Mabuse is a manipulative genius who wields power over others, while Beckert is a pitiable figure controlled by his own compulsions. Yet both characters disrupt the fragile balance of their respective societies, revealing the cracks in social and moral structures.

In Dr. Mabuse, the titular character’s crimes are grandiose and theatrical, reflecting the chaotic, disillusioned zeitgeist of post-World War I Germany. Mabuse’s ability to manipulate society mirrors the instability of the Weimar Republic, where political and economic systems seemed vulnerable to exploitation. The film’s subtitle, “A Picture of the Time,” reinforces this connection, presenting Mabuse not just as an individual villain but as a symbol of societal corruption and chaos.

M, on the other hand, offers a more intimate examination of crime, shifting the focus from societal systems to individual psychology and collective fear. Beckert’s murders expose the vulnerabilities of a society grappling with its own sense of morality and justice. The collaboration between the police and criminals in the hunt for Beckert highlights the desperation of a city willing to blur ethical boundaries in the name of security. Where Dr. Mabuse critiques systemic power, M delves into the moral ambiguities of justice, forcing viewers to confront uncomfortable questions about human behavior and responsibility.

Technology and Surveillance

Both films also emphasize the role of technology and observation in the pursuit of control. In Dr. Mabuse, technology is a tool of manipulation, with Mabuse using his skills in hypnosis and psychological warfare to dominate others. His ability to orchestrate chaos from the shadows reflects anxieties about unseen forces shaping society. In M, technology plays a more neutral role, with tools like surveillance, maps, and coordinated searches used to track Beckert. The camera itself becomes an omniscient observer, echoing the film’s themes of surveillance and control.

A Society on Trial

Perhaps the most striking connection between the two films is their shared critique of society itself. In Dr. Mabuse, the decadence and corruption of Berlin provide fertile ground for Mabuse’s schemes, suggesting that societal decay enables the rise of figures like him. Similarly, in M, the underground trial of Beckert reflects the mob mentality and moral uncertainty of a society desperate for justice. Both films place society on trial, questioning whether it is equipped to handle the forces that threaten its stability.

Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler and M are not merely crime films but profound meditations on the nature of power, fear, and human behavior. Through their exploration of societal vulnerabilities, technological observation, and moral ambiguity, the two films complement each other, offering a multifaceted critique of the worlds they depict. Together, they form a cinematic dialogue on the fragility of social order and the enduring challenge of reconciling justice with the complexities of human nature.

Dr. Mabuse and M: From Societal Corruption to Innocence Lost

Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922) and M (1931) represent two pivotal explorations of crime and its relationship to society, forming a continuum in Lang’s cinematic critique of social order. In Dr. Mabuse, crime operates within a concealed yet pervasive underworld, where corruption spreads like a contagion, infecting the fabric of Weimar society. By the time of M, Lang narrows his focus to the devastating consequences of this criminal chaos as it spills over into the most vulnerable parts of society—specifically, its children. Through these films, Lang traces a progression from the manipulative, abstract power of a criminal mastermind to the intimate horror of violence inflicted on the innocent, offering a stark commentary on how societal decay and unchecked criminality ultimately harm its weakest members.

From Corruption to Chaos: The Criminal Underworld in Dr. Mabuse

In Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler, crime exists as a shadowy but structured force, orchestrated by the titular character. Mabuse is a master manipulator who uses his intellect, hypnotic abilities, and a network of operatives to destabilize society for his personal gain. His schemes—rigging stock markets, sabotaging the rich, and undermining political stability—are far-reaching, impacting the public indirectly but profoundly.

This underworld operates in parallel to society, exploiting its weaknesses without immediate visibility. Mabuse’s actions represent a predatory system that thrives on societal instability, mirroring the fears of Weimar Germany, where economic crises, political upheaval, and moral decay provided fertile ground for such figures to flourish. Though Mabuse’s crimes are grand in scale, they are primarily directed at the elites and institutions of society, keeping the general public largely peripheral to his schemes.

However, the film suggests that such a system cannot remain contained indefinitely. Mabuse’s descent into madness at the film’s conclusion is emblematic of a broader unraveling. His loss of control foreshadows the eventual collapse of the boundary between the criminal underworld and the public sphere, setting the stage for M, where the repercussions of such corruption are felt directly by ordinary people—especially children.

The Underworld Spills Over: The Tragedy of M

In M, Lang shifts his focus from the machinations of a single mastermind to the devastating human consequences of criminal activity when it invades the everyday lives of citizens. The child murderer Hans Beckert, played by Peter Lorre, represents the horrifying culmination of unchecked deviance. Unlike Mabuse, whose crimes manipulate systems, Beckert’s actions are personal and visceral, targeting the most innocent and defenseless members of society.

The film’s depiction of Beckert’s crimes underscores the transition from systemic corruption to direct harm. While Dr. Mabuse focuses on societal elites as the victims of crime, M shows how the criminal underworld’s influence spills over into the streets, preying on children and creating a pervasive atmosphere of fear. This transition reflects Lang’s broader critique of a society that has failed to contain the consequences of its own corruption.

Beckert’s crimes trigger a dual response: the police intensify their surveillance efforts, while the criminal underworld mobilizes to capture him. This collaboration between law enforcement and organized crime highlights the porous boundary between the two realms. The criminals are not acting out of moral responsibility but out of self-interest, frustrated by the increased police pressure disrupting their activities. The irony is stark: those who operate outside the law now become its enforcers, demonstrating how deeply crime has infiltrated every level of society.

Children as the Ultimate Victims

The focus on children in M marks a profound shift in Lang’s exploration of crime. In Dr. Mabuse, the victims are largely adults—wealthy elites, gamblers, and political figures who are complicit, to some degree, in their own downfall. In M, however, the victims are entirely innocent. This shift underscores the ultimate consequence of societal decay: when systems of justice and morality fail, it is the most vulnerable who suffer.

Beckert’s crimes are not just acts of individual pathology but symptoms of a larger societal failure. The public’s fear and hysteria, the ineffectiveness of the police, and the criminal underworld’s opportunism all point to a community unable to protect its children. Lang uses this focus to expose the fragility of the social contract, suggesting that when society fails to address corruption and crime at its roots, it inevitably leads to the exploitation and harm of its weakest members.

The Intersection of Surveillance and Innocence

Both films emphasize the role of observation and control in addressing crime, but their approaches differ significantly. In Dr. Mabuse, surveillance is a tool of power, wielded by Mabuse to manipulate and exploit. In M, surveillance becomes a collective effort, as society turns its gaze inward to hunt Beckert. However, this collective observation is not entirely altruistic; it is motivated by fear and self-preservation rather than a genuine concern for justice or morality.

The chilling irony of M is that the community’s combined efforts to track Beckert mirror Mabuse’s manipulative tactics. The same tools of observation that Mabuse used for control are now used to hunt a murderer, blurring the line between justice and vengeance. This parallel suggests that society has internalized the predatory logic of the criminal underworld, turning it against itself in an attempt to restore order.

Complementary Narratives of Decline

Together, Dr. Mabuse and M form a cohesive narrative about the dangers of societal corruption and the unchecked spread of criminal influence. In Dr. Mabuse, crime is an abstract force that destabilizes systems, operating in the shadows and preying on the powerful. In M, the consequences of this destabilization become horrifyingly tangible, as the violence spills into the public sphere and targets children.

Lang uses these films to critique the failure of societal systems to address crime at its root. In Dr. Mabuse, the failure is one of control, as a corrupt society allows figures like Mabuse to thrive. In M, the failure is one of protection, as the community proves incapable of safeguarding its most vulnerable members. The films complement each other by revealing different stages of a shared problem, ultimately illustrating the devastating consequences of a society unable to confront and contain its own moral and structural weaknesses.

Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler and M are profound examinations of crime and its relationship to society, tracing a trajectory from systemic corruption to personal tragedy. Through their complementary narratives, Lang explores how the criminal underworld, left unchecked, spills over into society, culminating in the exploitation and harm of its most innocent members. By highlighting the failures of social systems to address these issues, Lang offers a timeless critique of power, morality, and the fragility of human civilization.

Muybridge’s Legacy in Lang’s Dr. Mabuse and M: Dissecting Crime and Society Beyond Entertainment

Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922) and M (1931) are landmark films that transcend the boundaries of entertainment to offer profound meditations on criminology and sociology. These works are united by Lang’s detailed exploration of crime and its impact on society, but they also share a conceptual lineage with the groundbreaking innovations of Eadweard Muybridge. Muybridge’s motion studies, which meticulously dissected human and animal movement, laid the groundwork for cinema as both a technological and philosophical tool. By breaking down motion into sequences of observable data, Muybridge transformed visual storytelling into a medium capable of revealing hidden truths about behavior, intent, and society. Lang builds on this legacy, using the cinematic medium to dissect criminal behavior and societal dynamics in a way that engages the public with questions of justice, morality, and human vulnerability.

Muybridge’s Innovations and the Birth of Analytical Cinema

Eadweard Muybridge’s motion studies in the late 19th century introduced the idea that movement could be captured, analyzed, and understood through sequential photography. His experiments, such as The Horse in Motion and Animal Locomotion, broke time into measurable intervals, revealing details imperceptible to the naked eye. These studies were not merely technical achievements but also philosophical inquiries into the nature of motion and behavior. By isolating individual moments within a continuous action, Muybridge demonstrated how observation could uncover patterns and insights, transforming abstract phenomena into tangible, analyzable data.

This approach directly influenced the development of cinema, turning it into a medium capable of examining complex ideas beyond mere storytelling. Muybridge’s work suggested that film could serve as a tool for understanding human behavior and societal dynamics, paving the way for filmmakers like Fritz Lang to use the medium as a lens for criminology and sociology.

From Muybridge to Mabuse: Dissecting Criminal Mastery

In Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler, Lang channels Muybridge’s analytical approach to explore the mechanisms of power and crime. Mabuse’s actions, though larger-than-life, are presented with a clinical precision that mirrors Muybridge’s methodical breakdown of motion. Lang uses the cinematic medium to reveal Mabuse’s manipulations in detail, from his psychological domination of victims to his orchestration of stock market crashes and political unrest.

Just as Muybridge’s motion studies revealed the hidden mechanics of movement, Lang’s film dissects the invisible forces that drive societal instability. Mabuse’s crimes are not random acts of violence but calculated disruptions that expose the fragility of societal structures. Through the lens of Lang’s camera, the audience becomes an observer, much like Muybridge’s viewers, gaining insight into the patterns and consequences of Mabuse’s actions.

This dissection of Mabuse’s criminal empire transcends traditional storytelling, transforming the film into a sociological study of corruption and control. Lang invites viewers to consider how systems of power and greed, when left unchecked, can infiltrate and destabilize society. In this sense, Dr. Mabuse functions as an extension of Muybridge’s legacy, using the cinematic medium to analyze not just movement but the broader dynamics of human behavior and societal interaction.

M: The Fragmentation of Time and Society

Lang’s M takes Muybridge’s influence a step further by applying the principles of motion analysis to the psychology of crime and the collective response to deviance. The film’s fragmented narrative structure, which cuts between disparate actions and perspectives—the murderer’s movements, police investigations, and the criminal underworld’s plotting—mirrors Muybridge’s sequential breakdown of motion. Each scene functions as a piece of a larger puzzle, contributing to a chilling portrait of a society in crisis.

Beckert’s crimes and the ensuing manhunt are presented with an almost forensic precision, emphasizing observation and analysis over sensationalism. The rhythmic editing and deliberate pacing echo Muybridge’s systematic approach, allowing the audience to scrutinize not just the killer’s behavior but also the societal structures attempting to apprehend him. The film’s focus on surveillance—visual tracking of Beckert’s movements and the auditory clue of his whistle—further underscores the legacy of Muybridge’s technological observation, illustrating how cinema can reveal truths invisible to the unaided senses.

Bringing Criminology and Sociology to the Public

Both Dr. Mabuse and M transcend mere entertainment by presenting criminological and sociological concepts to a mass audience, continuing the democratizing impulse initiated by Muybridge’s public exhibitions of motion studies. Muybridge’s work made complex ideas about movement and behavior accessible to a wide audience, transforming abstract scientific inquiry into a visual experience that could be understood by anyone. Lang adopts a similar approach, using the accessibility of cinema to engage viewers with profound questions about crime, justice, and society.

In M, this is particularly evident in the climactic underground trial of Beckert. The scene shifts the focus from the individual criminal to society itself, turning the film into a public forum for moral and philosophical debate. Beckert’s plea for understanding—claiming that he cannot control his impulses—forces the audience to confront uncomfortable questions about the root causes of crime. Is Beckert a victim of mental illness, societal neglect, or inherent evil? The film offers no easy answers, instead challenging viewers to grapple with the complexities of justice and societal responsibility.

Similarly, Dr. Mabuse uses its sprawling narrative to explore the broader sociological implications of crime. Mabuse’s manipulation of financial and political systems exposes the vulnerabilities of society, prompting viewers to consider how power and corruption operate within their own world. Lang’s meticulous depiction of Mabuse’s schemes transforms the film into a case study in the dynamics of control, offering insights that extend far beyond the confines of its narrative.

Cinema as a Tool for Understanding Society

By building on Muybridge’s innovations, Lang elevates cinema into a medium for public education and engagement with complex ideas. Muybridge’s motion studies proved that technology could reveal hidden truths about behavior and movement, offering new ways of understanding the world. Lang extends this principle to the realms of criminology and sociology, using film to dissect crime and its impact on society.

In Dr. Mabuse, Lang explores how criminal power operates within and against societal systems, highlighting the dangers of corruption and the fragility of order. In M, he shifts the focus to the consequences of crime, illustrating how societal failures to address systemic issues ultimately harm the most vulnerable. Together, the films reflect Lang’s belief in cinema as a tool for revealing truths and fostering public understanding, continuing the legacy of Muybridge’s analytical and democratizing approach.

Muybridge’s innovations in motion studies laid the groundwork for a cinematic language capable of analyzing complex phenomena, from individual behavior to societal dynamics. Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler and M build on this foundation, using film to dissect the mechanisms of crime and its consequences for society. By engaging viewers with criminological and sociological questions, Lang transcends entertainment, transforming cinema into a medium for public inquiry and understanding. In doing so, he carries forward Muybridge’s vision of technology as a tool for uncovering hidden truths, offering a timeless critique of power, morality, and human vulnerability.

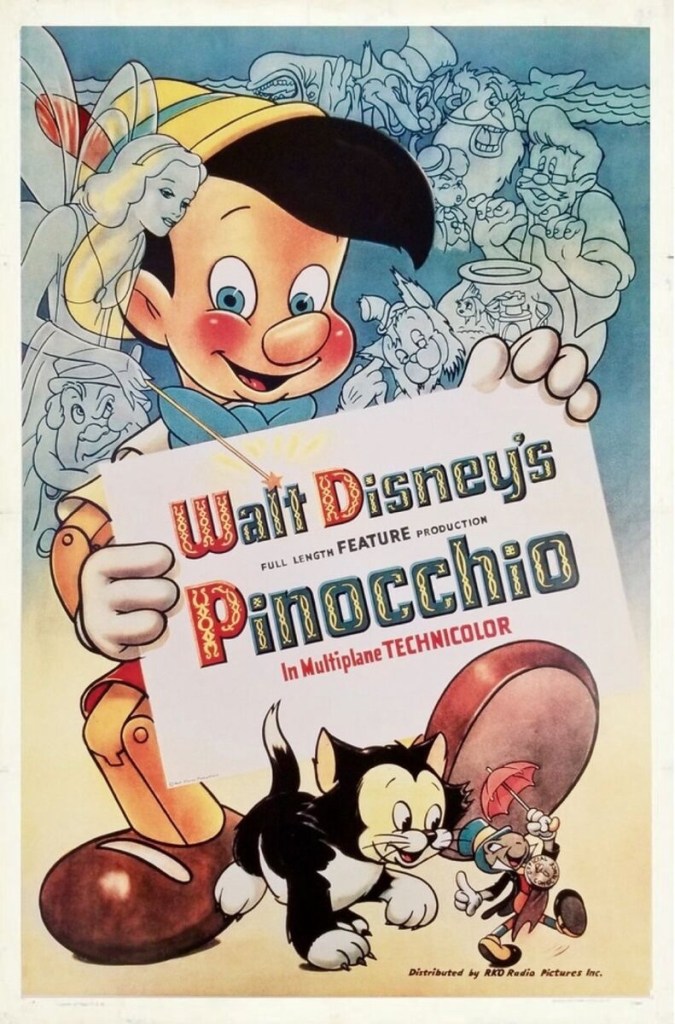

The 1940 Disney film Pinocchio might seem worlds apart from the innovations of Eadweard Muybridge, Fritz Lang’s M, and their contributions to cinema and sociological inquiry, but a closer examination reveals a fascinating lineage. At its core, Pinocchio inherits the cinematic language and philosophical questions about motion, observation, and morality that Muybridge and Lang helped establish. Through its groundbreaking animation techniques and exploration of human behavior, Disney’s Pinocchio continues this tradition by using motion and storytelling to engage with moral and societal themes, presenting them to a mass audience in an accessible and emotionally resonant way.

1. Muybridge: The Foundation of Motion and Animation

Eadweard Muybridge’s photographic motion studies, which deconstructed movement into sequential frames, laid the groundwork for animation and its reliance on the illusion of motion. His pioneering efforts resonate profoundly in Disney’s Pinocchio.

The film’s lifelike movement—such as Pinocchio’s clumsy, puppet-like steps evolving into confident strides—embodies Muybridge’s focus on replicating real motion. Disney animators, like Muybridge, meticulously observed human and animal movement to create the illusion of life. Additionally, Muybridge’s exploration of human gestures as vehicles for emotion finds an artistic counterpart in Disney’s work, where characters’ nuanced motions—Pinocchio’s curiosity, Geppetto’s tenderness, Jiminy Cricket’s exasperation—transform the story into an emotional experience.

2. Lang’s Sociological Exploration and Pinocchio’s Morality

Fritz Lang’s M used cinema to delve into societal morality and deviance, themes that are similarly explored in Pinocchio, though in allegorical form.

Lang’s portrayal of observation and societal judgment finds a parallel in Pinocchio, where figures like the Blue Fairy, Jiminy Cricket, and Monstro embody moral oversight. Pinocchio is constantly watched, guided, or judged, reflecting Lang’s vision of a society that scrutinizes individual behavior. Both works also grapple with crime and punishment: Lang humanizes the deviant, suggesting crime as a product of circumstance, while Pinocchio portrays characters like Lampwick as victims of external influences. Redemption, a key theme in both, is tied to action; just as Lang examines ethical dilemmas, Pinocchio’s humanity is defined by his ultimate choice to act selflessly.

3. Technology, Motion, and Emotional Engagement

Disney’s Pinocchio extends the technological innovations of Muybridge and Lang, pushing animation’s storytelling potential.

Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope, which gave motion to still images, and Lang’s cinematic framing and editing techniques paved the way for Disney’s use of the multiplane camera. This innovation, employed extensively in Pinocchio, added depth and realism, immersing audiences in the story’s fantastical world. Motion, a central narrative device for Muybridge and Lang, is also pivotal in Pinocchio. Whether it’s Pinocchio’s transformation from wooden rigidity to lifelike fluidity or the frenetic chaos of Pleasure Island, movement drives the emotional and narrative stakes, echoing the importance of motion as a storytelling tool in Muybridge’s studies and Lang’s films.

4. Philosophical and Sociological Themes in Pinocchio

Muybridge and Lang introduced profound questions about humanity and morality that find expression in Pinocchio.

Muybridge’s exploration of human motion and Lang’s focus on societal morality are synthesized in Pinocchio’s central question: What does it mean to be human? The film argues that true humanity lies not in form or function but in moral choice and responsibility. External forces—whether societal pressures in M or physical influences in Muybridge’s work—also shape Pinocchio’s journey, highlighting the tension between personal agency and external manipulation.

Lastly, Pinocchio reflects Lang’s and Muybridge’s shared interest in observation and self-awareness. As Jiminy Cricket acts as Pinocchio’s conscience, guiding him toward self-reflection and moral accountability, the film mirrors Lang’s examination of societal surveillance and Muybridge’s technological observation of the human form. In both works, the act of watching—whether by society, technology, or the self—becomes a mechanism for understanding and transformation.

5. Presenting Morality to a Public Audience

Muybridge’s public exhibitions and Lang’s socially charged cinema made complex ideas accessible to large audiences. Disney’s Pinocchio continues this legacy by presenting profound moral and philosophical questions in an engaging, family-friendly format. Themes like the consequences of dishonesty, the dangers of temptation, and the rewards of selflessness resonate universally, ensuring that the film’s sociological and philosophical messages reach a wide audience.

Disney’s Pinocchio stands on the shoulders of Muybridge and Lang, inheriting their innovations in motion, observation, and sociological exploration. Muybridge’s scientific dissection of movement enabled animators to breathe life into characters, while Lang’s use of cinema to examine morality and behavior laid the groundwork for Pinocchio’s allegorical storytelling. By blending technical innovation with profound moral inquiry, Pinocchio extends the legacy of these pioneers, proving that cinema, whether through photography, film, or animation, is a powerful medium for exploring what it means to be human.

Criminology

The Disney film Pinocchio (1940) weaves a profound narrative around the dangers children face, presenting themes of criminology, moral corruption, and societal responsibility in a way that engages a broad public audience. These themes, while universal, resonate with the lineage of cinematic exploration pioneered by Eadweard Muybridge and Fritz Lang. Muybridge’s work with motion studies and Lang’s sociological inquiry in M (1931) provided the intellectual and technical groundwork for Pinocchio’s exploration of crime, deviance, and the moral challenges children face in navigating a world fraught with danger.

1. The Dangers Facing Children: Pleasure Island as a Criminal Trap

In Pinocchio, Pleasure Island functions as a vivid allegory for societal forces that exploit vulnerable children, paralleling the themes of deviance and societal neglect seen in Lang’s M. The boys who are lured to the island by promises of fun and indulgence are ultimately transformed into donkeys—literal beasts of burden—reflecting the consequences of falling prey to criminal manipulation. The Coachman, who orchestrates this scheme, represents a predatory figure who exploits children’s innocence for personal gain. His actions echo the concerns of early criminology, as seen in M, where crime is portrayed as a symptom of societal failure and moral decay. Additionally, Pleasure Island symbolizes broader societal neglect of children’s welfare. Just as Lang’s M critiques a society unable to protect its most vulnerable, Pinocchio warns of the dangers children face when left without proper guidance or protection.

2. Pinocchio and the Criminology of Influence