I do not have to wait. I cannot wait.

The Union is here. This victory is real. This feeling we all share- it connects us to history. It connects us to God. Their greatest mistake? They underestimated God. This is a true victory- a victory steeped in truth, rooted in history. A triumph won legitimately. This is real. We do not need to fabricate lies or invent illusions to rally others. No schemes, no falsehoods. Because this is real. In truth, this is victory. In truth, this is power. This is a moment that stands unshaken by doubt, unyielding to time. The Union Forever. Their second mistake was this: they betrayed their own feelings. Had they been true to what they felt, they could have been spared the shame, the damnation, the descent into hell. Staying true to their hearts would have led them to the straight path, to clarity and redemption. But instead, they chose deception. Instead, they relied on manipulation and intimidation to pursue their ends. A mistake rooted in denying their own truth. They seek to take from you what they would never allow to be taken from themselves. That is the essence of their treachery—their ultimate folly. To not be true to your feelings is to sever yourself from the very compass that guides you to truth and righteousness. It is a betrayal of the self, a denial of the inner voice that connects you to what is real, to what is just. Without honesty in your feelings, you lose your way, falling prey to doubt, shame, and darkness. It is the first step toward manipulation, deceit, and ruin. To be true to your feelings is to stand in the light of authenticity, walking the straight path with courage and clarity. To deny your feelings is not only a betrayal of the self but also a rejection of true rationality. Feelings and reason are not enemies—they are allies, each strengthening the other. Rationality without honesty to your emotions becomes cold calculation, devoid of purpose or humanity. Likewise, emotions without the guidance of reason can spiral into chaos. To be true to your feelings is to acknowledge the truths they reveal, but to guide them with reason is to ensure those truths are acted upon wisely. Together, they form the foundation of clarity and integrity. Ignoring your feelings creates a fracture within, leading to self-deception and ultimately irrational choices—choices fueled by fear, manipulation, or denial. True rationality requires an alignment of heart and mind, of feeling and thought. Only then can you walk the straight path with both wisdom and authenticity.

To be true to your feelings while guided by reason is essential to being correct in thought and action. Descartes, in his Meditations, sought to strip away falsehood and uncertainty, arriving at truth by questioning everything that could be doubted. Similarly, your feelings, when honestly acknowledged, are undeniable facets of your reality—anchors to your lived experience. However, like Descartes’ process, feelings must be tested by reason to ensure they are not deceptive, mere shadows of truth. Being correct requires harmony between emotion and rationality. Feelings alert us to something deeply true within us, but reason ensures that truth aligns with reality. Denying your feelings introduces doubt and error, just as Descartes warned against accepting anything unexamined. Yet, relying solely on emotion without the rigor of rational thought leads to misjudgment, much like clinging to assumptions in the face of doubt. To be correct, as Descartes might argue, is to ground your beliefs and actions in clear, self-evident truths—truths revealed by reason, but not disconnected from the undeniable reality of your feelings. Both are necessary for navigating the path to certainty and ensuring your judgments are aligned with what is true and just.

To be delusional is to exist in a state where one denies reality and clings to an illusion, often born from unresolved desperation or inner conflict. Freud and his contemporaries, particularly those like Karl Jaspers or Pierre Janet, examined hallucination and delusion as not just deviations from reality but as defenses against unbearable truths. Hallucinations, in their view, arise when the mind’s desperation can no longer reconcile with the reality it denies, creating fabricated worlds as a refuge from despair. This desperation leads to irrationality, where decisions are no longer guided by reason or authenticity but by the frantic need to sustain the illusion. In this state, the delusional person often acts in ways that appear foolish, destructive, or “stupid” because their actions are no longer grounded in reality or logic—they serve only to perpetuate the false narrative that shields them from the truth. The mind, in its desperation, abandons rationality entirely and instead leans on manipulation, self-deception, or impulsive acts to maintain the illusion. When one denies their feelings or the reality of their situation—when they reject truth—they slide into a state of delusion. In this delusion, desperation becomes the driving force, and reason is cast aside. As Freud might suggest, repression and denial only build tension until the mind fractures under the weight, leading to irrationality. Acting stupidly, then, is not just a product of ignorance but of this internal war between reality and illusion—a war that can only be

resolved by returning to truth, reason, and self-awareness.

Drug abuse plays a profound role in hallucinations, often serving as a catalyst for delusional thinking. Substances like LSD, methamphetamine, or PCP alter brain chemistry, disrupting normal cognitive functioning and perception of reality. These drugs can induce vivid hallucinations, paranoia, and a distorted sense of self and environment. The mind, under the influence of these substances, becomes detached from reason, often amplifying feelings of desperation or unresolved psychological conflicts. For those already teetering on the edge of mental instability, drugs can act as a trigger, driving them deeper into delusion and irrational behavior. In criminology, particularly in works like Mindhunter and the field of behavioral profiling, the link between drug abuse, hallucinations, and criminal behavior is well-documented. Behavioral profilers like John Douglas, the author of Mindhunter, highlight how substance abuse can exacerbate latent violent tendencies or fuel impulsive acts. For example, many serial offenders or violent criminals profiled by the FBI exhibited patterns of drug use that not only facilitated their disconnection from reality but also dulled their moral inhibitions. Drugs often become a vehicle for masking internal pain or enabling fantasies that might otherwise remain suppressed. Hallucinations induced by drugs can drive individuals to commit crimes in a desperate attempt to act on the distorted reality their mind perceives. A drug-fueled delusion might convince someone that they are acting in self-defense or fulfilling some grandiose purpose, when in reality, they are committing heinous acts born of paranoia or psychosis. Profilers in Mindhunter and related studies analyze these behaviors, understanding how the interplay of drug abuse, mental instability, and desperation creates a predictable pattern of irrational, often violent actions. Criminology has found that desperation, whether arising from delusions, addiction, or a combination of the two, often manifests in behaviors that defy logic. Drug abuse doesn’t just amplify this desperation—it transforms it into a driving force that overrides reason. This understanding has been pivotal in behavioral profiling, where experts like Douglas piece together the psychological and environmental factors leading to criminal acts. By examining the role of substances in distorting reality, profilers can better predict and understand the actions of those whose desperation turns into criminality.

John Douglas, in Mindhunter, takes a pragmatic and unapologetic view of criminals, particularly violent offenders, asserting that society’s safety must come before any misplaced fascination or sympathy for the criminal. He emphasizes that many of these individuals are not just products of unfortunate circumstances but deeply flawed, often delusional people who lack the capacity—or willingness—to confront reality. This delusion, compounded by drug abuse or psychological instability, fuels their actions, creating a dangerous and unpredictable threat to society. Douglas argues that there has been too much attention placed on understanding or sympathizing with these individuals. While criminology benefits from profiling to prevent future crimes, the goal is not to humanize or excuse the criminal but to protect potential victims. Many of these offenders, in his words, are “losers” driven by desperation, delusion, and a twisted need to exert power over others. Their inability to accept responsibility for their actions often manifests as a rejection of reality itself, making them both irrational and dangerous. From his perspective, prisons exist not as a place for reform for these individuals but as a means of ensuring the safety of society. Delusional criminals, especially those under the influence of drugs or driven by psychosis, are often beyond rehabilitation. Their behavior is not just a deviation from the norm but a fundamental threat to those who live by the rules of society. Allowing them back into the public space out of misguided sympathy or an overemphasis on their personal stories only endangers others. For Douglas, criminals must be seen for what they are—dangerous individuals who prioritize their delusions, desires, and impulses over the lives of others. Their actions, whether influenced by drug abuse or inherent pathology, necessitate imprisonment because society’s primary concern must always be the protection of the innocent. This view serves as a counterpoint to the increasing focus on the criminal’s background and motivations, reminding us that understanding the “why” does not negate the need for accountability or consequence. In Douglas’s framework, prison is not just punishment; it is a necessary shield for society against those whose desperation and delusion have made them irredeemable.

John Douglas’s perspective on the insanity plea and criminal responsibility reflects his broader philosophy: criminals are not victims of their delusions but active participants in their descent into darkness. In Mindhunter, he makes it clear that the insanity defense is often a grotesque insult to the victims and their families, reducing heinous acts to a supposed lack of control or awareness. To Douglas, this plea undermines the reality that these individuals consistently made deliberate choices—choices that revealed not only their ability to act rationally but also their determination to reject reality in favor of their own delusions. Douglas argues that what ties all criminals together, regardless of their specific crimes, is their responsibility for their behavior. These are not people who accidentally found themselves in criminality; they are individuals who made conscious, repeated decisions to live outside of societal norms, driven by their delusional egos and desires. Far from being irrational actors, they often display frightening consistency in their choices, habits, and patterns of behavior—so much so that behavioral profilers like Douglas can identify and predict their actions. This consistency demonstrates that their delusions, while powerful, do not absolve them of accountability. They are deliberate losers, as Douglas might frame it, choosing to reject reality and instead manipulate, harm, or destroy in pursuit of their selfish aims. The hallmark of these criminals is their inability—or refusal—to live in reality. They construct false worlds around their desires, frustrations, or power fantasies, and they act within those constructs while knowing they are out of step with the rules of society. Their delusions, while profound, do not strip them of agency. On the contrary, their crimes reflect a calculated abandonment of responsibility and a choice to indulge in these delusions rather than confront the real world. The victims and their families pay the price for these choices, making any attempt to excuse such behavior with an insanity plea a moral affront. In this context, Douglas reinforces the necessity of holding criminals accountable not just for the sake of justice but as a recognition of their agency. Their behaviors, while rooted in delusion, are chosen, consistent, and ultimately irreconcilable with a functioning society. By refusing to live in reality, they forfeit their place within it, and their incarceration becomes a logical and moral imperative—not as punishment alone, but as protection for the innocent and as a statement that choices have consequences, even for those who live in the world of delusion. John Douglas’s work in criminal profiling, as explored in Mindhunter, highlights a startling truth about violent criminals: their behaviors, no matter how shocking or depraved, are disturbingly predictable. Through decades of studying serial killers, rapists, and other violent offenders, Douglas and his colleagues in the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit identified consistent patterns in the psychology, methods, and lifestyles of these individuals. These patterns reveal that far from being criminal masterminds or uniquely complex individuals, most criminals are, in Douglas’s words, “losers”—failures in society who act out of desperation, delusion, and a profound inability to live in reality. Douglas’s approach to profiling is rooted in identifying the shared characteristics that these individuals display. Across the board, they are often socially isolated, emotionally stunted, and consumed by fantasies that they cannot reconcile with the real world. Their inability to achieve success, connection, or fulfillment in normal life leads them to construct alternative realities in which they have power, control, or significance—usually at the expense of others. These fantasies become the driving force behind their crimes, which are not random but deliberate and methodical, shaped by their need to assert dominance or fulfill their warped desires. What makes these behaviors so predictable is their consistency. Douglas emphasizes that criminals leave “signatures” in their crimes—repeated, unique elements that reveal their personality and psychological state. These signatures are born from their delusions and personal failures, making them identifiable and, in many cases, predictable. For instance, serial offenders often escalate in a pattern, refining their methods and obsessively repeating certain actions because they are tied to their fantasies or compulsions. Even their non-criminal behavior, such as their employment history, social interactions, or habits, reflects a pattern of failure and detachment from reality. In essence, their lives and crimes revolve around consistent themes of inadequacy and delusion. Douglas doesn’t romanticize criminals or give them undue credit. He views them as failures—individuals who couldn’t navigate life within the bounds of society. Their crimes are often not acts of brilliance but extensions of their loser status, attempts to assert control or meaning in lives otherwise defined by failure. For example, many violent offenders come from abusive or neglectful backgrounds, but rather than using this adversity as motivation to rise above, they wallow in self-pity and blame others for their shortcomings. Their delusional behavior is an attempt to rewrite the narrative of their lives, casting themselves as powerful or important when, in reality, they are anything but. This shared “loser” archetype is why behavioral profiling works. By understanding the common traits and behaviors of violent criminals—such as their obsessive need for control, their narcissistic fantasies, or their inability to form healthy relationships—profilers like Douglas can predict their next moves, identify them before they strike again, and ultimately bring them to justice. These patterns also highlight the futility of glorifying or overanalyzing criminals. They are not exceptional individuals but deeply flawed, broken people who choose to reject reality and live in delusion. For Douglas, this predictability is both a tool and a sobering reality. It reinforces his belief that criminals must be held accountable for their choices, as their actions are deliberate, calculated extensions of their loser mentality. They are not products of chance or uncontrollable madness but failures of society who consciously choose to harm others rather than confront their inadequacies. By understanding their predictability, society can not only catch and stop them but also ensure that their delusions do not eclipse the reality of their victims’ suffering.

In modern times, there has been a disturbing fetishization of sociopathy and an increasing tendency to romanticize or admire certain types of antisocial behavior as signs of strength, independence, or even virtue. This cultural phenomenon reflects a deeper fracture within the framework of civilized society, where traits like cunning, ruthlessness, and disregard for others are at times linked with success or power. This dynamic is reminiscent of the discourse explored in Jacques Derrida’s The Beast and the Sovereign, where the sovereign and the beast are positioned as polar yet intertwined figures—representatives of power, control, and rebellion. However, the notion of criminality as it applies to individuals like those profiled by John Douglas operates outside this philosophical discourse. Criminality, as Douglas makes clear, does not stem from mere antisocial behavior or cunning; it arises from a consistent, deliberate loser mentality rooted in delusion. The modern glamorization of sociopathy and antisocial traits—often seen in popular media and culture—fails to grasp the reality of criminal behavior as Douglas defines it. True criminality, particularly violent or predatory behavior, is not a result of cunning or power. It is born out of repeated failure, a refusal to engage with reality, and a desperate attempt to create a false narrative of control or significance. These criminals are not sovereigns or beasts—they are delusional losers whose actions reveal a complete lack of virtue or strength. Douglas’s insights dismantle the idea that criminality is the product of an inherently antisocial or rebellious mindset. Instead, it is a symptom of a deeply flawed psyche—a psyche that chooses to reject accountability, live in delusion, and lash out in acts of destruction rather than confront personal inadequacies. These individuals fail not only in their societal roles but in their personal responsibilities to themselves and others. Their criminal acts are not clever or cunning but predictable and pathetic extensions of their internal failures. Derrida’s exploration of the beast and the sovereign as symbolic figures in the discourse of power and legitimacy does highlight the inherent contradictions of civilized society. Still, these concepts are worlds apart from the delusional, loser mentality that Douglas identifies as the root of criminality. The sovereign may assert power through dominance and law, and the beast may challenge that power through rebellion or cunning, but neither encapsulates the reality of the violent criminal. The criminal is neither a sovereign nor a beast—they are not agents of power or rebellion but prisoners of their own delusions. They lack the strength or clarity to confront reality, choosing instead to act out of desperation and failure. In this context, criminality becomes a self-perpetuating cycle. These individuals repeatedly make the same choices—choices grounded in their inability to function in a civilized society. Their behavior does not reflect strength, cunning, or rebellion; it reflects weakness, failure, and an unwillingness to take responsibility. To romanticize or fetishize these traits, as is often done in modern discourse, is to misunderstand the true nature of criminality. It is not a deviation from the social order that carries any inherent virtue or critique of that order—it is the predictable outcome of a delusional loser mentality, as Douglas so clearly specifies.

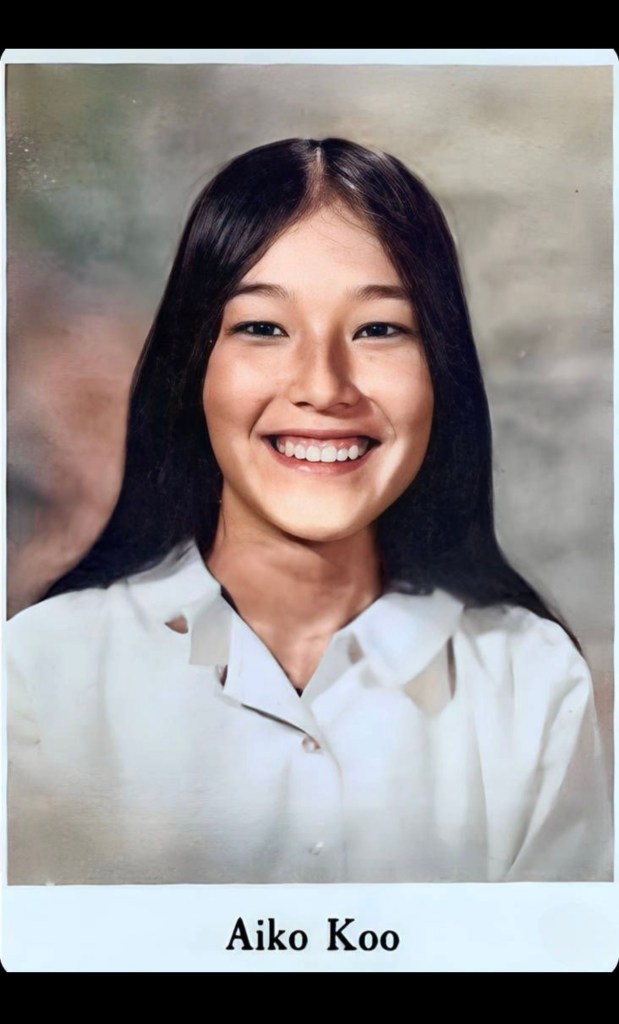

The murder of 15-year-old Aiko Koo by Edmund Kemper on September 14, 1972, is one of the most chilling examples of his manipulative and calculated behavior. Aiko Koo was a young high school student who missed her bus to a dance class in Berkeley, California. She decided to hitchhike, a common and culturally accepted practice at the time. Edmund Kemper, already with several murders to his name, spotted her on the side of the road. Using his practiced charm and imposing presence, he offered her a ride. His large stature and calm demeanor helped him seem trustworthy, making her feel safe in accepting his offer. Once Koo was in his car, Kemper began driving her toward a remote area. He had developed a pattern by this point: gaining his victims’ trust before isolating them and revealing his violent intentions. After driving far from any populated area, he pulled a gun on her. Despite her young age, Aiko reportedly attempted to reason with Kemper, but his mind was already made up. Kemper restrained her, taping her mouth shut and rendering her unconscious. Afterward, he removed her from the car and laid her on the ground. While she was vulnerable and defenseless, he sexually assaulted her. This act was consistent with his pattern of seeking ultimate control over his victims, reducing them to objects for his gratification. Following the assault, Kemper used Aiko’s own scarf to strangle her to death. The act of strangulation is slow and deliberate, further reflecting Kemper’s need for power and domination over his victims. He later admitted to experiencing a sense of satisfaction and empowerment during the act, as it fulfilled his violent fantasies. After killing Aiko Koo, Kemper placed her body in the trunk of his car. He then drove around the area with her corpse in the trunk, even stopping occasionally to admire her lifeless body. This grotesque behavior underscored his pathological need to maintain control over his victims, even in death. Later, Kemper took Aiko’s body back to his apartment, where he carried out further mutilation and dismemberment. Necrophilia was a hallmark of his crimes, and he admitted to engaging in sexual acts with her corpse before cutting her into pieces. He disposed of her remains in various locations, making it difficult for authorities to recover her body. The most disturbing detail of this murder is Kemper’s brazen behavior immediately afterward. The day after killing Aiko, he attended a scheduled meeting with court psychiatrists as part of his parole requirements from previous offenses. He presented himself as calm, collected, and rehabilitated. Astonishingly, the psychiatrists were so impressed with his apparent progress that they recommended sealing his juvenile criminal record-completely unaware that Aiko’s severed head was in the trunk of his car during their session. Aiko Koo’s murder is emblematic of Edmund Kemper’s calculated, manipulative approach to his crimes. His ability to present a façade of normalcy while engaging in such horrific acts highlights the delusional yet highly structured mindset that John Douglas and other behavioral profilers studied. Kemper’s consistent methods -choosing vulnerable young women, using deception to isolate them, and carrying out acts of domination-made his behavior predictable but no less horrifying. This crime exemplifies Douglas’s concept of the “delusional loser” in criminal profiling. Kemper’s violent actions were not acts of brilliance or cunning; they were manifestations of his pathological failure to engage with reality, his obsession with control, and his desire to assert power over those he saw as weaker. His crimes were the culmination of a life defined by failure, delusion, and an inability to confront his inadequacies.

The concepts of the Beast, the Sovereign, and the Loser represent different archetypes in their relationships to power, reality, and societal norms, and understanding their distinctions sheds light on the psychology of criminality and broader societal dynamics. The Beast, as explored in Derrida’s The Beast and the Sovereign, represents a figure of primal instinct and rebellion, one who exists outside the bounds of civilization and law. The Beast is untamed and acts according to its own nature, rejecting societal constraints and authority. While it is seen as a threat to order, the Beast operates with a certain authenticity, embodying raw freedom and instinct. Its defiance of norms is often perceived as a challenge to the Sovereign’s authority. The Sovereign, on the other hand, is the figure of ultimate authority and control, standing above the law yet enforcing it upon others. The Sovereign asserts power not by rejecting societal norms, like the Beast, but by existing beyond their reach. In Derrida’s framework, the Sovereign claims legitimacy through mastery, cunning, and the ability to command others, often using both force and rhetoric to maintain their position. The Sovereign’s power is seen as absolute, yet it is tied to the systems it oversees, making it dependent on maintaining order and control over the Beast and other figures of rebellion. The Loser, in contrast, is not a figure of power or rebellion but one of failure and delusion. As described in Mindhunter and John Douglas’s profiling work, the Loser is someone who rejects reality not out of defiance, like the Beast, but out of inadequacy and fear. The Loser constructs an illusion of power or significance to mask their personal failures, often lashing out in destructive ways that harm others. Unlike the Beast, who operates on instinct, the Loser acts out of desperation, seeking to escape their inadequacies rather than embrace them. And unlike the Sovereign, the Loser has no true power, only the delusional belief in their ability to control others or rewrite their reality. In the context of criminality, individuals like Edmund Kemper fit the archetype of the Loser. They lack the authenticity of the Beast or the authority of the Sovereign. Instead, they act from a place of profound inadequacy, using manipulation and violence as tools to create a false sense of power. Their actions are predictable, rooted in repeated patterns of delusion and failure, and ultimately serve to reinforce their status as disconnected from reality and incapable of true sovereignty or freedom. While the Beast and the Sovereign are locked in a philosophical interplay between rebellion and authority, the Loser exists on a lower plane entirely, consumed by personal failure and detached from both power and authenticity. Understanding these distinctions helps illuminate the psychology of criminal behavior and its place within societal structures.

Technology has significantly exacerbated the ability of “losers”—those consumed by failure and delusion—to act on their destructive impulses. The rise of digital platforms and online communities has provided these individuals with both a stage to amplify their fantasies and tools to bring their make-believe worlds into a dangerous, tangible reality. The internet, with its anonymity and lack of immediate accountability, has allowed people to retreat further from reality into curated, self-reinforcing echo chambers. These spaces enable delusional individuals to connect with others who share their grievances or warped views, further validating their fantasies. Instead of confronting their failures or inadequacies, they find a community that encourages or normalizes their irrational behavior. This process allows their desperation to fester unchecked, making them more likely to act out. Social media platforms play a pivotal role in this, offering an illusion of power, influence, and significance. For someone already disconnected from reality, the ability to craft a persona or seek validation online creates a make-believe world where they can imagine themselves as important, respected, or feared. When these individuals fail to achieve such recognition in the real world, they may resort to drastic, often violent actions to bridge the gap between their fantasies and reality. In cases of mass violence or other extreme behaviors, technology has often served as a breeding ground for delusion and a means to carry it out. Moreover, the accessibility of information has transformed the way individuals plan and execute these acts. Technology has provided a wealth of resources to research, organize, and even mimic violent behaviors seen in media or through online interactions. This has made it easier for those desperate to assert power in their delusional narratives to act out with chilling efficiency. For example, individuals who idolize previous perpetrators can study their methods, emulate their crimes, and even broadcast their intentions through livestreams or social media posts, creating a twisted cycle of inspiration and replication. Gaming and virtual reality can also deepen this problem for certain individuals. While most people engage with these technologies in healthy ways, for those who are already disconnected from reality, they can become a tool to blur the line between fantasy and the physical world. The immersive nature of these technologies reinforces their delusional perceptions of themselves, often exacerbating feelings of inadequacy when their imagined power does not translate into real-life interactions. Ultimately, technology enables these individuals to avoid confrontation with reality, reinforcing their delusions instead of challenging them. It allows them to construct elaborate fantasies where they are in control, powerful, or significant, even as their actual lives spiral further into isolation and failure. When their desperation reaches a breaking point, their actions are no longer confined to the virtual world but manifest in real, devastating ways. The consequences are stark. Technology has not only amplified these delusions but has made it easier for individuals to act on them, whether by accessing tools for harm, finding encouragement in fringe communities, or seeking infamy in the digital spotlight. Addressing this issue requires understanding the role technology plays in nurturing these impulses and developing systems that disrupt this cycle of delusion before it leads to irreversible harm.

Technology has dramatically amplified the ability of “losers”—those driven by delusion, inadequacy, and a hunger for control—to rise within government systems and commit crimes against humanity. Historically, oppressive regimes have relied on a mix of propaganda, bureaucratic control, and military power to achieve their goals. However, in the modern age, technology has exponentially increased their capacity to manipulate populations, consolidate power, and carry out acts of violence and repression on a previously unimaginable scale.

First, technology has revolutionized surveillance. Authoritarian leaders or corrupt governments can now use advanced surveillance systems, artificial intelligence, and big data analytics to monitor, control, and suppress dissent. For example, tools like facial recognition, mass data collection, and phone tracking allow regimes to identify and target individuals who oppose their rule. This technological reach ensures that even minor acts of rebellion or criticism are swiftly detected and neutralized. Such technology creates an environment of fear, where individuals are stripped of their ability to resist tyranny, leaving them at the mercy of leaders who abuse power. Second, propaganda has become far more effective in the digital age. Governments can now use social media platforms and state-controlled media to flood public discourse with misinformation, disinformation, and controlled narratives. Through algorithms designed to maximize engagement, they can reach millions instantly, shaping public opinion and silencing opposition. Leaders with inadequate qualifications or moral character can use these tools to create a false image of competence or heroism, further cementing their grip on power. By creating echo chambers, they foster environments where alternative views are not only dismissed but actively vilified, further isolating and discrediting dissenters. Technology also allows governments to weaponize the economy against their citizens. Digital currencies, online banking systems, and centralized digital IDs enable regimes to track and control individual financial activity. In cases where people oppose the government, their access to funds or essential services can be cut off instantly. This ability to weaponize technology against a population magnifies the power of oppressive regimes and ensures that their citizens remain entirely dependent on state systems. On the battlefield, technology has introduced a new dimension to crimes against humanity. Drones, cyberattacks, and autonomous weapons systems have made it easier for governments to commit acts of violence with minimal accountability. Drone strikes, for instance, have been used in extrajudicial killings, often justified under vague terms like “national security.” These tools allow governments to commit acts of violence at a distance, reducing the human cost to their own forces while magnifying the suffering of those they target. Furthermore, technology has enabled systematic repression of entire populations. In cases like China’s treatment of the Uyghur population, advanced systems such as AI-driven predictive policing, social credit scores, and ubiquitous surveillance infrastructure have been used to detain, monitor, and strip away the freedoms of millions. Such systems allow governments to dehumanize and criminalize specific groups with unprecedented efficiency, scaling their crimes to levels that were previously unimaginable. Perhaps most insidious is how technology enables these crimes to be committed under the guise of legality or progress. Bureaucratic systems enhanced by technology create the illusion of order and rationality, even as they facilitate atrocities. Leaders who fail morally and ethically can hide behind the complexity of these systems, deflecting responsibility while enacting policies that result in mass suffering. Technology has also made it easier for these regimes to maintain power on the global stage. By hacking elections, spreading disinformation internationally, or using cyber tools to destabilize other nations, these governments ensure that their crimes are less likely to face scrutiny or retaliation. Leaders who might have otherwise been constrained by diplomatic or military consequences can now wield their technological capabilities to neutralize opposition globally. In sum, technology has become a tool for delusional, power-hungry leaders in government to transform their inadequacies into far-reaching acts of violence and repression. It allows them to extend their control over populations, dehumanize opposition, and commit atrocities with unparalleled efficiency and impunity. This convergence of technology and authoritarianism has created a chilling new paradigm where crimes against humanity can be scaled, automated, and perpetuated in ways that make resistance and accountability increasingly difficult.

The quote, often attributed to François de La Rochefoucauld, states,

Hypocrisy is the homage vice pays to virtue.

It suggests that even the most corrupt or oppressive entities must acknowledge the value of virtue, at least superficially, in order to justify their actions. For oppressive regimes, this means crafting narratives that their actions—no matter how violent or repressive—are necessary, moral, or virtuous in the broader context. They must frame their crimes as acts of national defense, liberation, or stability, even when their true motives are rooted in delusion, greed, or power. This hypocrisy becomes glaring in how many regimes justify their wars and repressive measures by claiming to fight terrorism while covertly funding, enabling, or even manufacturing terrorist cells. These regimes thrive on creating chaos and enemies, as it allows them to position themselves as the protectors of stability and order. By funding or allowing the existence of terrorist groups, they create the very threats they claim to be combating, perpetuating an endless cycle of violence and control. The hypocrisy is clear: regimes publicly decry terrorism while covertly enabling it as a justification for their policies, wars, or expansion of state power. Technology has exacerbated this dynamic, transforming these manipulative strategies into a hyper-efficient system of control and misinformation. The advent of advanced surveillance tools, cyber warfare, and artificial intelligence has allowed oppressive regimes to simultaneously wage covert wars and shape public opinion with unprecedented precision. Through propaganda amplified by social media algorithms and digital platforms, regimes can blur the lines between reality and fiction, painting their violent or repressive actions as necessary evils to maintain order or defend against existential threats. Terrorist cells—whether real, exaggerated, or fabricated—become the centerpiece of these narratives, providing a convenient justification for endless wars, repressive domestic policies, and expanded state power. By shaping public perception through online misinformation campaigns, regimes can rally support for their actions, stifle dissent, and delegitimize critics, all while maintaining a veneer of moral authority. The “extremely cold war” we face today is not one defined by direct global confrontation but by covert operations, disinformation, and proxy conflicts. Technology has enabled this war to unfold across multiple domains—cyberspace, financial systems, and public opinion—without traditional battlefields. Oppressive regimes use cyberattacks to destabilize other nations while exploiting fears of terrorism to justify their own aggressive policies. They manipulate social media to seed division in other countries, distracting from their own crimes while creating an environment where truth itself is contested. Moreover, regimes use technology to suppress dissent domestically, often under the guise of counterterrorism. Surveillance programs, facial recognition, and AI-driven predictive policing allow governments to monitor and target individuals under the pretext of maintaining security. Oppressive leaders, who in the past might have relied on physical force alone, now use data as a weapon to preemptively eliminate threats to their power. Simultaneously, terrorist groups have also adapted to this technological cold war, using the same tools to recruit, fundraise, and spread their ideologies. This further blurs the line between state-sponsored violence and independent terrorism, as oppressive regimes exploit this overlap to justify their own authoritarian measures. By painting dissenters or minority groups as potential terrorists, governments justify mass surveillance, internment camps, and even acts of genocide, all under the guise of national security. The cold war between regimes has thus evolved into a highly calculated game of misinformation, cyber warfare, and proxy battles. While oppressive governments claim to protect virtue, their actions reveal the underlying vice: a desperate need to maintain power at any cost. Technology has only magnified this hypocrisy, allowing delusional leaders to manipulate global narratives while committing atrocities behind a digital smokescreen. In the end, the homage these regimes pay to virtue—through their rhetoric and justifications—underscores the pervasive need for truth and accountability in a world increasingly shaped by deceit.

The advancement of technology has opened new avenues for governments to manipulate, fund, and weaponize criminal elements, creating fragmented “loser communities” and instigating violence in foreign countries as part of covert strategies to destabilize adversaries and maintain global influence. This phenomenon reveals how modern technology serves not only as a tool for surveillance and control but also as a weapon to exploit individuals and groups already inclined toward violent or extremist behavior. Online platforms and encrypted communication tools have enabled governments to interact with criminal or extremist groups without leaving traditional paper trails. Through anonymous forums, social media, and encrypted messaging apps, regimes can covertly provide financial backing, strategic guidance, and ideological reinforcement to these groups. This not only amplifies the reach of these organizations but also allows governments to maintain plausible deniability. They fund and manipulate these groups under the radar, directing their activities toward creating instability in targeted nations. One of the most effective tactics is the fostering of “loser communities”—online networks of disenfranchised individuals who share grievances, insecurities, or extremist ideologies. These communities are often composed of individuals who feel alienated from society and are searching for a sense of identity or purpose. Governments, particularly authoritarian regimes, exploit these vulnerabilities by infiltrating such spaces through state-sponsored operatives or artificial intelligence-driven propaganda tools. By amplifying divisive rhetoric, promoting conspiracy theories, or glorifying acts of violence, they radicalize these individuals into becoming unwitting agents of chaos. For example, foreign powers may infiltrate online forums centered on extremism, incel culture, or other fringe ideologies, encouraging violence or subversion in targeted countries. By fostering a shared sense of victimhood and offering a narrative of empowerment through destruction, these actors manipulate individuals into acting as proxies for their geopolitical aims. These tactics have been observed in cases where online radicalization leads to acts of domestic terrorism or political unrest, with links tracing back to foreign influence campaigns. The funding of these groups often occurs through cryptocurrencies or other untraceable financial methods, which technology has made widely accessible. Governments can anonymously provide financial support to criminal or extremist organizations, enabling them to acquire weapons, spread propaganda, or recruit new members. These funds are often laundered through layers of digital transactions, making it difficult to establish direct links between the regime and the criminal activities it sponsors. In addition to funding, governments use online platforms to instigate violence and unrest in foreign countries. They employ bots and fake accounts to spread inflammatory messages, incite protests, or promote divisive ideologies that fracture social cohesion. By targeting specific demographics or exploiting existing societal tensions, these actors create an environment ripe for violence and destabilization. This strategy has been used in disinformation campaigns to influence elections, exacerbate ethnic or religious divides, and even provoke armed conflicts. A particularly insidious aspect of this strategy is its reliance on individuals who are already disconnected from reality—those who embody the “loser” archetype described by John Douglas. These individuals are often emotionally vulnerable, socially isolated, and drawn to extremist ideologies as a way to reclaim a sense of power or purpose. Governments exploit this desperation, providing the tools and narratives that push these individuals toward violent action. By doing so, they turn personal inadequacies into geopolitical weapons. The results are devastating. Acts of violence instigated by these loser communities create chaos within targeted nations, undermining public trust, destabilizing governments, and diverting resources to address internal conflicts. Meanwhile, the regimes that instigated the violence remain hidden, claiming innocence while achieving their strategic objectives. This strategy represents a new form of warfare, one that leverages technology to weaponize individuals and groups at a scale and efficiency never before possible. In summary, the advancement of technology has given governments unprecedented tools to manipulate and fund criminal and extremist elements. By fostering loser communities online and instigating violence in foreign countries, regimes exploit societal fractures and human vulnerabilities for geopolitical gain. This underscores the urgent need for international accountability and robust countermeasures to address the exploitation of technology for destabilizing and violent purposes.

The Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, which occurred on December 14, 2012, in Newtown, Connecticut, remains one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history and a tragic reminder of the devastating impact of gun violence. The incident involved the killing of 20 children and six adult staff members at the school. It was carried out by a lone gunman, Adam Lanza, who also killed his mother before the attack and took his own life afterward. Adam Lanza, a 20-year-old with a history of mental health challenges, began his rampage at the home he shared with his mother, Nancy Lanza. Early that morning, he shot and killed his mother while she was in bed. Nancy had reportedly purchased several firearms and trained with her son at shooting ranges, believing it to be a way to bond with him and manage his struggles. Unbeknownst to her, these weapons would later be used in the horrific attack. After killing his mother, Lanza drove to Sandy Hook Elementary School armed with multiple firearms, including a Bushmaster XM15-E2S semi-automatic rifle, two handguns, and a shotgun left in his car. Upon arriving at the school around 9:35 a.m., Lanza forced his way inside by shooting tr gha glass panel near the locked front entrance. Once inside, Lanza began his assault, targeting classrooms filled with young children and their teachers. Over the span of approximately five minutes, he systematically shot and killed 20 first-grade children, all between six and seven years old, and six adult staff members who tried to protect the students. The bravery of the teachers and staff was evident, as many tried to hide or shield the children during the chaos. Tragically, their efforts could not prevent the massive loss of life. When law enforcement arrived at the scene in response to 911 calls, Lanza turned one of the handguns on himself, taking his own life before he could be apprehended. The entire attack lasted less than 11 minutes but left an indelible mark on the nation. The aftermath of Sandy Hook was characterized by profound grief and an intense debate about gun control, mental health, and school safety. Advocates called for stricter firearm regulations, including bans on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines, which were used during the shooting. However, despite widespread public outcry and efforts to pass new legislation, meaningful gun reform at the federal level has remained elusive. The Sandy Hook tragedy also fueled a disturbing wave of conspiracy theories. Certain individuals and groups claimed the event was a “hoax” or “false flag operation,” accusing grieving families and survivors of being “crisis actors.” These baseless claims caused further trauma to those affected by the tragedy, leading to lawsuits against prominent conspiracy theorists for defamation. Sandy Hook remains a somber milestone in American history, highlighting the ongoing challenges of addressing gun violence, mental health care, and societal divisions. The legacy of the victims—20 innocent children and six courageous educators-serves as a heartbreaking reminder of the need for comprehensive action to prevent such tragedies in the future.

Adam Lanza’s life on the internet provides crucial insights into the factors that contributed to his isolation, radicalization, and eventual actions at Sandy Hook Elementary School. His online activity reflected a pattern that has become disturbingly common in the profiles of school shooters: a descent into alienation, obsessive interests, and the cultivation of extremist or nihilistic ideologies through virtual communities. Lanza spent much of his time online in forums and communities that validated his growing misanthropy and paranoia. According to investigations, he frequented websites that fixated on mass shootings, violent crimes, and controversial ideologies. These online spaces, often anonymous, fostered a toxic culture where acts of violence were discussed, analyzed, and sometimes even glorified. Lanza reportedly posted in forums under pseudonyms, sharing his thoughts on topics such as school shootings, the human condition, and nihilistic philosophies, reinforcing his isolation from the real world. For example, Lanza displayed an obsession with the 1999 Columbine High School shooting, a crime that has inspired a grim “canon” within certain online subcultures. He studied the shooters, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, viewing them not as perpetrators of tragedy but as individuals to be analyzed, understood, or even emulated. This obsessive focus on Columbine and other mass shootings is part of a broader trend: the internet has created spaces where isolated individuals can bond over shared grievances, obsessions, or ideologies, even when those ideas are destructive. Additionally, Lanza engaged in online discussions that highlighted his growing misanthropy and detachment from society. He expressed a fascination with violence and an increasing disdain for humanity, particularly children, as investigations revealed. This toxic feedback loop in online communities amplified his already significant mental health struggles, providing him with an environment that validated his distorted worldview rather than challenging it. This pattern of internet-fueled radicalization is not unique to Adam Lanza. Many school shooters in recent years have shown similar trajectories: young, socially isolated individuals who retreat into online communities where their frustrations, alienation, and grievances are amplified. These online spaces serve as echo chambers, fostering feelings of victimhood and empowering their violent impulses. In some cases, they even encourage would-be shooters by glorifying previous acts of mass violence. The anonymity and lack of accountability in online interactions play a significant role in this phenomenon. Platforms like message boards, gaming forums, and social media have become breeding grounds for toxic ideologies and extremist behaviors. They allow individuals like Lanza to immerse themselves in narratives that dehumanize others, glorify violence, and normalize the idea of turning anger and alienation into acts of mass destruction. These communities often draw in individuals who feel rejected by society, giving them a distorted sense of belonging and purpose in a culture that celebrates their grievances and potential for infamy. This trend of online radicalization is tied to the wave of school shootings that has plagued the United States in recent decades. In many cases, shooters have left behind digital footprints revealing their participation in similar online spaces, their fascination with previous shootings, and their desire for notoriety. The internet not only facilitates the sharing of extremist ideas but also provides would-be perpetrators with access to detailed information about planning and executing such attacks. From studying the tactics of previous shooters to researching weaponry, the internet has become an accelerant for individuals already inclined toward violence. Adam Lanza’s life on the internet reflects a disturbing intersection of isolation, mental health struggles, and the toxic influence of online communities. These factors, when combined, contributed to his radicalization and the eventual tragedy at Sandy Hook Elementary School. The broader trend of online-fueled violence underscores the urgent need to address the role of technology in enabling and amplifying these destructive behaviors. From regulating harmful online spaces to improving early intervention for isolated and vulnerable individuals, tackling this issue requires a comprehensive understanding of how the internet has shaped the modern wave of school shootings.

If René Descartes were to comment on the modern issues of alienation, online radicalization, and violence like school shootings, he might focus on the role of reason, the failure of critical thinking, and the human tendency to fall into error when disconnected from truth and rational self-examination. Descartes emphasized the importance of grounding knowledge in clear, distinct, and rational thought, free from bias and false assumptions. In his famous Meditations on First Philosophy, he advocated for doubting everything that could be uncertain as a way to uncover indubitable truths. Applying this principle to modern challenges, Descartes might argue that many of the individuals involved in these destructive behaviors, such as Adam Lanza and other isolated figures, have abandoned rationality and fallen victim to unchecked delusions, which the internet exacerbates by providing spaces that validate and amplify those delusions. Descartes believed the mind is prone to error when it allows passions and external influences to override reason. He might view the modern internet as a medium that magnifies this vulnerability. In online spaces, individuals are drawn to ideologies, misinformation, and echo chambers that appeal to their emotions, grievances, and insecurities, rather than encouraging rational discourse or self-reflection. Descartes might critique the lack of a rigorous method for engaging with information, pointing out that such environments allow irrationality to flourish unchecked. Further, Descartes would likely stress the importance of individual responsibility for pursuing truth and developing rational self-control. He held that humans are endowed with the capacity for reason and that moral and intellectual progress depends on using it to govern passions and seek the good. In the case of isolated individuals or “loser communities” on the internet, he might argue that they have failed to exercise their rational faculties, instead surrendering to emotional impulses and false beliefs that lead to destructive actions. On a societal level, Descartes might critique the lack of structure or education that fosters rationality and critical thinking. He believed that errors often stem from a failure to guide the will in alignment with clear and rational understanding. Modern technologies, while powerful tools, often lack the safeguards to encourage such disciplined thinking, and instead, they enable the spread of dangerous ideologies. Descartes might view this as a failure of both individuals and societies to create systems that prioritize reason and truth-seeking over unrestrained passion and ignorance. Regarding the wave of school shootings, Descartes might reflect on how these actions represent a rejection of rationality and humanity. He believed in the importance of living according to higher principles—principles grounded in reason and the pursuit of the good. The perpetrators of these crimes, consumed by delusions and disconnected from reality, would likely exemplify for Descartes the dire consequences of failing to engage in rational self-examination and the dangers of a will untethered from clear thinking. Descartes would likely see these issues as symptoms of a deeper failure to align human behavior with reason and truth. He would advocate for cultivating critical thinking and self-awareness as essential antidotes to the errors that lead to radicalization, violence, and societal harm. For Descartes, the solution lies in fostering a disciplined and rational mind, both individually and collectively, to counteract the passions, misinformation, and delusions that dominate much of the modern world.

When bringing together Descartes’ emphasis on rationality with Emmanuel Levinas’ focus on ethics and the idea of being “true to your feelings,” particularly as explored in Otherwise than Being, we find two complementary perspectives on the tension between selfhood, responsibility, and human behavior. Levinas, in Otherwise than Being, critiques traditional philosophy’s focus on self-centered ontology—the study of being as defined by the individual subject. Instead, he emphasizes ethics as “first philosophy,” arguing that true humanity is found not in self-contained reason but in the ethical responsibility to the Other (the face of another person, the call of another’s vulnerability). For Levinas, being true to your feelings is not about indulging selfish passions or desires but about responding authentically to the ethical call of others. It is through this radical openness to the Other that we transcend the selfish nature of being and find moral grounding. From Levinas’ perspective, the failures of individuals like Adam Lanza, or others who succumb to delusional violence, stem from a refusal to respond to the ethical responsibility inherent in their relationship to others. Their inward focus on grievances, alienation, and a make-believe sense of self completely neglects the call of the Other—the faces of the children, parents, and community they harm. In Levinasian terms, their actions represent a collapse of ethics into a perverse ontology, where the self becomes an isolated, violent center of reality, rejecting the infinite obligation to the Other. Levinas’ work offers a critique of this rejection, arguing that to be true to one’s feelings must mean to recognize the weight of one’s responsibility for others. Feelings, in this sense, are not mere internal passions but are shaped by the vulnerability of others calling for recognition, care, and response. Technology, which often creates spaces of isolation and detachment from real human relationships, exacerbates this disconnection, allowing individuals to retreat into delusional self-centered fantasies, as seen in the patterns of online radicalization. For Levinas, this is a failure of the ethical self, where the Other is ignored or dehumanized rather than recognized as a source of infinite moral obligation. When juxtaposed with Descartes, who emphasizes the importance of rationality, Levinas introduces a deeper dimension: that rationality must be guided by ethical responsibility to others. Descartes’ rational self-reflection might identify the delusions or errors of the mind, but Levinas would argue that such clarity is insufficient without the ethical demand to respond to the suffering or vulnerability of others. For Levinas, the question is not just whether you are being rational or irrational, but whether your feelings and actions honor your responsibility to those around you. The actions of violent individuals like Adam Lanza, from Levinas’ perspective, represent the ultimate betrayal—not just of rationality but of the ethical self. Their feelings are not true in the Levinasian sense, because they are not grounded in an authentic relationship with others. Instead, they collapse inward into isolation, nihilism, and delusion, severing the individual from the infinite call of responsibility that Levinas sees as the foundation of human existence. Levinas might also critique the role of society in failing to foster environments that prioritize ethical relationships. Technologies that isolate people, communities that ignore the vulnerable, and systems that perpetuate alienation all contribute to the breakdown of ethical responsibility. To counter this, Levinas would likely argue that being true to your feelings requires stepping beyond the self and into an ethical relationship with others, where feelings are not just self-serving impulses but are informed by care, responsibility, and the face-to-face encounter with the Other. While Descartes focuses on rationality and self-examination as the foundation of human thought and action, Levinas would shift the focus to ethical responsibility, emphasizing that being true to your feelings means recognizing and responding to the vulnerability of others. The failures of delusional individuals and the systems that enable them stem, for Levinas, from a refusal to engage in this deeper ethical relationship. To transcend this failure, society and individuals must rediscover the primacy of the Other in shaping feelings, thoughts, and actions.

Levinas’ notion of infinite responsibility is not some abstract metaphysical ideal—it is grounded in his phenomenological claim that reality itself, in its most fundamental sense, is structured by encounters with otherness. For Levinas, the self’s very existence is constituted by its relationship to the Other, a relationship that is inherently ethical because it demands response and responsibility. Levinas rejects the primacy of the autonomous self, as championed by thinkers like Descartes, arguing instead that our experience of the world is irreducibly ethical and relational. The face of the Other, in Levinas’ terms, disrupts the self’s tendency to objectify and totalize, challenging us to recognize the Other as irreducible and infinite. This encounter with the face is not simply a momentary ethical demand—it is the foundation of reality itself. To “be true to your feelings” in this Levinasian framework is not about turning inward to validate personal impulses but about responding authentically to the call of the Other, who places demands on us through their vulnerability and difference. Derrida, in Violence and Metaphysics, expands on this idea by situating Levinas’ philosophy within a broader critique of Western metaphysics. Derrida argues that traditional metaphysics, from Plato to Descartes and beyond, has sought to reduce otherness to sameness—an effort to understand and categorize the Other within the framework of the self’s knowledge. This, for Derrida, is a form of epistemic violence, as it denies the radical alterity of the Other. Levinas’ insistence on the irreducibility of otherness represents, for Derrida, a necessary rupture with this metaphysical tradition. The encounter with the Other is a moment of resistance to the totalizing violence of comprehension—it is an acknowledgment that reality is constituted by difference, by an ethical disruption of the self’s attempts to dominate. The connection to modern phenomena, such as acts of violence or the alienation fostered by technology, becomes especially pertinent here. The delusional individuals who commit atrocities like school shootings are fundamentally disconnected from the encounter with otherness. Instead of being disrupted and called to responsibility by the presence of others, they retreat into a solipsistic, self-contained world. Their actions reflect a totalizing mindset—a refusal to recognize the Other as infinite and irreducible, reducing them instead to objects to be destroyed or dominated. This is, in Derrida’s terms, a violent metaphysics, where the failure to encounter the Other as Other leads to acts of literal violence. Technology exacerbates this alienation by further insulating individuals from genuine encounters with otherness. Online communities and echo chambers create spaces where individuals are never truly disrupted by difference. Instead, they inhabit environments where their delusions are reinforced, and their worldview remains unchallenged. This avoidance of the ethical encounter with the Other, as Levinas and Derrida might argue, is not just a personal failing—it is a societal structure that prioritizes sameness, isolation, and the reduction of reality to the self’s fantasies. Levinas and Derrida would likely see the wave of violence and radicalization in this context: as the result of a systemic failure to maintain the ethical primacy of the Other in our shared reality. Rather than encountering otherness phenomenologically and being called to responsibility, individuals withdraw into solipsistic worlds where others are dehumanized or erased entirely. For Levinas, this is the ultimate ethical failure; for Derrida, it is the violence inherent in metaphysical systems that seek to erase difference. Levinas’ insistence that reality is an encounter with otherness—and Derrida’s critique of metaphysical violence—offers profound insight into the alienation and violence that pervade modern life. To “be true to your feelings” in this framework means to remain open to the ethical disruption posed by the Other and to resist the solipsistic closure that leads to violence and domination. Addressing these modern crises requires not only structural change but also a reorientation of how we, as individuals and societies, understand and encounter reality itself.

Levinas, while critiquing much of traditional Western philosophy, is deeply aligned with Descartes on certain crucial points, particularly the idea of perfection in Meditations on First Philosophy. Levinas, like Descartes, acknowledges the transcendent dimension of the self’s experience. However, Levinas reorients Descartes’ concept of perfection by situating it not in abstract metaphysical thought but in the ethical encounter with the Other. This connection becomes even clearer when examined alongside Derrida’s essay Violence and Metaphysics, which unpacks and critiques Levinas’ ideas while simultaneously highlighting their profound relevance. In Meditations, Descartes reflects on the idea of God as a being that is perfect and infinite, contrasting it with the imperfection and finitude of the self. For Descartes, the very fact that humans can conceive of perfection and infinity is evidence of a transcendent source outside themselves—God. Levinas builds on this notion of infinity, but he moves it from the realm of metaphysical speculation to phenomenology and ethics. For Levinas, infinity is not a concept grasped by thought; it is experienced in the ethical demand presented by the Other. When we encounter another person, their vulnerability and irreducible difference transcend our capacity to fully comprehend or master them. This is what Levinas refers to as the “infinite,” a notion that resonates with Descartes’ emphasis on perfection and infinity as that which exceeds the finite self. Levinas sees this ethical encounter as the foundation of reality itself. In his work Otherwise than Being, he argues that the self is constituted not as an isolated, autonomous subject but in its infinite responsibility to the Other. The Other, through their very presence, calls the self to an ethical relationship, disrupting the self’s tendency toward egocentrism and totalization. This ethical relationship is not optional or secondary; it is the primary structure of reality. In this sense, Levinas echoes Descartes’ focus on perfection and infinity but grounds it in the immediacy of lived experience and ethical obligation.

Derrida, in Violence and Metaphysics, explores the implications of Levinas’ critique of traditional metaphysics, including Descartes. Derrida agrees with Levinas that Western philosophy has often reduced the Other to the Same—that is, it has sought to comprehend, categorize, and ultimately dominate what is different. This reduction, Derrida argues, is a form of violence because it denies the Other’s irreducibility and singularity. However, Derrida also points out that Levinas’ project remains in tension with the metaphysical tradition it critiques. For instance, Levinas’ invocation of infinity and transcendence inevitably borrows from the very metaphysical language it seeks to surpass. Nevertheless, Derrida highlights Levinas’ crucial contribution: the insistence that ethics precedes ontology and that reality is fundamentally relational. This dynamic between Descartes, Levinas, and Derrida offers profound insights into modern issues of alienation, delusion, and violence. In Descartes’ framework, the self is capable of perceiving infinity and perfection, but it must strive toward them through rational inquiry and self-discipline. Levinas builds on this by emphasizing that the self encounters infinity not in abstract thought but in the ethical demand of the Other. Derrida, in turn, warns that the attempt to dominate or totalize the Other is a fundamental violence, one that distorts reality itself. When applied to modern phenomena, such as school shootings or online radicalization, these ideas take on a chilling relevance. Individuals who act out in violence, whether driven by delusions or isolation, reject the ethical call of the Other. Instead of being disrupted by the infinite responsibility posed by others, they retreat into solipsistic worlds where the Other is reduced to an object of hatred or domination. Technology exacerbates this problem by creating spaces where individuals can avoid genuine encounters with otherness. Online communities often serve as echo chambers, reinforcing delusions and validating violent impulses. From Levinas’ perspective, this is a collapse of ethics; from Derrida’s, it is a form of metaphysical violence. Levinas and Derrida together would argue that such acts of violence are not merely failures of rationality, as Descartes might see them, but failures of relationality. They represent a refusal to engage with the Other as infinite, instead reducing them to objects to be destroyed. This is where Levinas and Descartes align: the idea that the self, in recognizing something greater than itself—be it God for Descartes or the Other for Levinas—transcends its own limitations. For Levinas, the path to this transcendence is ethical; for Descartes, it is rational. Both, however, agree that human flourishing requires an acknowledgment of something beyond the finite self. Levinas reinterprets Descartes’ concept of perfection and infinity, grounding it in the ethical encounter with the Other, while Derrida critiques the metaphysical violence inherent in reducing the Other to the Same. Together, their ideas illuminate the failures of modernity: the rejection of the Other, the retreat into delusion, and the amplification of these tendencies by technology. Addressing these failures requires returning to the insights of Descartes, Levinas, and Derrida—recognizing that the self’s true existence lies not in isolation but in its relationship to what transcends it, whether through reason, ethics, or the infinite call of the Other.

In Emmanuel Levinas’ essay God and Philosophy, he responds to many of the ideas Jacques Derrida critiques in Violence and Metaphysics. In this essay, Levinas emphasizes his departure from traditional metaphysical frameworks while addressing Derrida’s concerns about the tension between ethics, transcendence, and metaphysics. Levinas reaffirms that his project is not an abstract metaphysical exercise but a phenomenological and ethical inquiry into the human encounter with otherness, including God, understood not as a concept but as an ethical and relational reality. In Violence and Metaphysics, Derrida argues that Levinas, while critiquing the violence inherent in reducing the Other to the Same (as traditional metaphysics tends to do), cannot fully escape metaphysical language and structures. Specifically, Derrida notes that Levinas’ use of terms like “infinity” and “transcendence” risks falling into the same patterns of thought Levinas aims to critique. Levinas addresses this in God and Philosophy by reframing his discussion of transcendence and God. He insists that God, like the ethical relationship with the Other, cannot be reduced to a metaphysical concept or an object of intellectual grasp. Instead, God is encountered in the ethical dimension of human relationships, in the infinite responsibility for the Other. Levinas argues that traditional Western philosophy, including the metaphysical tradition Derrida critiques, has often sought to render God a being among beings—something knowable, categorizable, and reducible to human thought. This, for Levinas, is an extension of the same totalizing impulse that reduces the Other to the Same. In contrast, Levinas presents God as absolute otherness—what he calls “otherwise than being.” God, like the Other, cannot be grasped, reduced, or comprehended within the structures of knowledge. Instead, God is experienced as a call, as an ethical demand that breaks into human existence and compels the self to transcend its egocentrism. This reframing of transcendence aligns Levinas’ thought more closely with his phenomenological focus. God is not an abstract perfection, as Descartes might suggest in Meditations, but is instead encountered in the ethical reality of the Other. The infinite responsibility for the Other is, for Levinas, a trace of God—a rupture in the self’s being that calls it to something beyond itself. This is where Levinas and Derrida partially converge: both agree that reducing the Other or God to the Same (as a knowable entity) is a form of violence. However, Levinas insists that this transcendence is not merely linguistic or conceptual but is the very structure of human existence. This dynamic becomes even more relevant when applied to modern issues such as violence, radicalization, and technology. The refusal to encounter the Other in their irreducible difference—whether it manifests as online echo chambers, school shootings, or broader societal alienation—reflects what Levinas critiques as the “violence of totality.” These failures to respond ethically to the Other are not merely individual shortcomings but systemic issues, exacerbated by the isolating and dehumanizing tendencies of technology. For Levinas, this alienation is a rejection of God—not in a theological sense but in the ethical sense of refusing to acknowledge the infinite demand that the Other places on the self. Derrida’s critique in Violence and Metaphysics helps deepen this analysis. He points out that any attempt to articulate transcendence risks reintroducing metaphysical structures, which can obscure the radical nature of Levinas’ ethical project. Levinas, in God and Philosophy, responds by doubling down on the idea that transcendence is not a concept but a lived reality. God is not “something” to be known or defined but is encountered in the ethical disruption of the self by the Other. In this sense, the encounter with God mirrors the encounter with the Other—it breaks into the self’s world, shattering its illusions of autonomy and mastery. When tied to Descartes, Levinas’ argument takes on additional resonance. Descartes posits the idea of perfection and infinity as a clue to the existence of God, rooted in the rational capacity to conceive of something greater than oneself. Levinas transforms this idea, suggesting that infinity is not encountered in thought but in the lived, ethical relationship with others. For Levinas, the recognition of the Other’s irreducible dignity and vulnerability is the true encounter with the infinite. Derrida’s critique of metaphysical violence and Levinas’ response in God and Philosophy converge here: both emphasize the need to resist totalizing frameworks that deny the transcendence of the Other. Levinas’ response to Derrida in God and Philosophy highlights the ethical dimension of transcendence, reframing it as a phenomenological reality grounded in the encounter with otherness. This aligns with his broader critique of metaphysics and his insistence on the primacy of ethics over ontology. When tied to modern issues like technological alienation or violence, this framework offers a powerful critique: the failure to respond ethically to the Other, amplified by isolating technologies and dehumanizing ideologies, is not just a societal problem but a rejection of the very structure of reality. Levinas, with Derrida as his interlocutor, challenges us to rethink not only philosophy but the ethical foundations of human life itself.