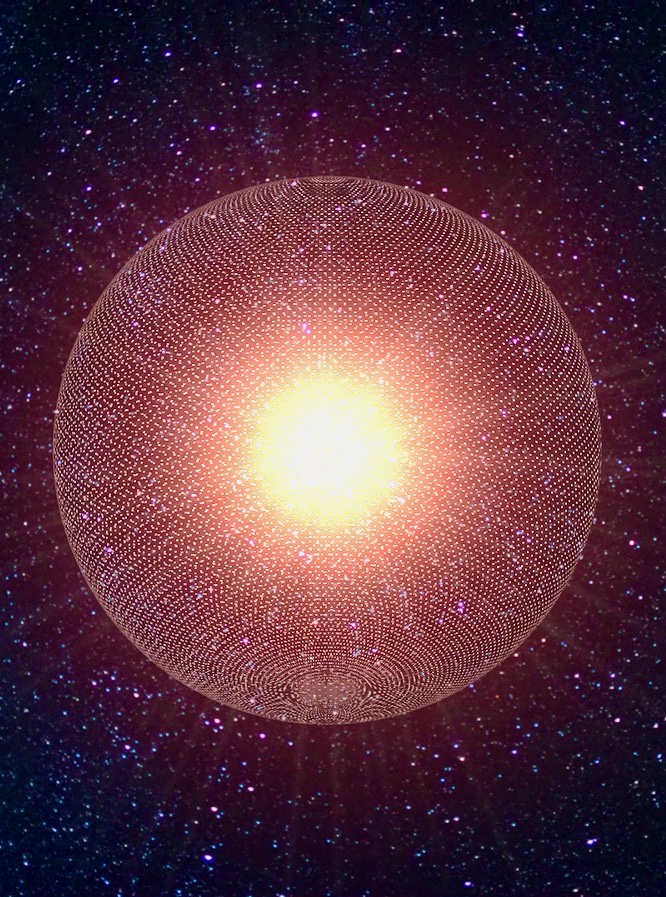

The Dyson sphere, a grand vision to encase the Sun and harness its vast energy, faces a gauntlet of challenges that make its completion by 2050 a Herculean task. The scale alone is mind-boggling—a structure spanning 150 million kilometers in radius demands materials beyond our current grasp, capable of enduring relentless solar radiation and cosmic wear. Construction in space, far from Earth’s comforts, requires robotics and manufacturing techniques we’ve barely begun to explore, while keeping such a behemoth stable against gravitational tugs and distributing its energy back to us poses riddles we’re nowhere near solving. Yet, faint glimmers of progress flicker in today’s world: space-based solar power experiments hint at capturing starlight, reusable rockets slash the cost of reaching orbit, and asteroid mining dreams tease the resources we’d need. To pull this off by 2050, we’d need a relentless, all-in push—think Manhattan Project urgency fused with SpaceX audacity—and even then, we’d be racing against physics itself.

The challenges are daunting but not insurmountable with a singular focus. Scale demands we think beyond Earth, tapping asteroids or even Mercury for raw materials, a feat requiring leaps in space mining tech already nascent in firms like Planetary Resources. Materials must evolve fast—carbon nanotubes and graphene, still lab curiosities, need to become industrial realities, tough enough to shrug off solar storms. Construction means mastering in-space assembly, scaling up from the International Space Station’s modest frame to a swarm of solar satellites, a concept more feasible than a solid shell. Stability could lean on AI-driven orbital corrections, while energy distribution might hinge on microwave beams, a tech Mitsubishi has tested over short distances. These aren’t pipe dreams but steep climbs, each needing breakthroughs in the next 25 years.

Today’s signs of progress offer a shaky foundation. NASA’s 2024 OTPS report pegs space-based solar power as viable by 2050, a stepping stone to Dyson’s dream. SpaceX’s Starship slashes launch costs, making mass deployment conceivable, while lunar base plans signal a foothold for resource extraction. Asteroid mining, though embryonic, aligns with the material hunger a Dyson swarm would have, and material science inches toward the strength we’d need. These threads suggest we’re not starting from zero, but the gap to a functioning sphere—or even a partial swarm—is vast, requiring a sprint where we’ve only begun to crawl.

To make this work by 2050, we’d need a brutal prioritization of effort. Start now, in 2025, with a global coalition—governments, tech giants, and spacefaring nations—pooling resources to flood low Earth orbit with infrastructure. By 2030, perfect reusable launch systems and deploy prototype solar satellites, testing energy transmission to Earth. Concurrently, ramp up asteroid mining, targeting near-Earth objects with robotic fleets to harvest metals and silicates, refining them in orbit by 2035. Materials science must hit overdrive, mass-producing advanced composites by 2040, while AI and robotics evolve to assemble a growing swarm of energy collectors. From 2040 to 2045, scale this swarm exponentially, launching thousands of units yearly, each beaming power back via microwave or laser. By 2050, aim for a partial Dyson swarm—perhaps capturing 1% of the Sun’s output, a staggering 3.8 x 10^24 watts—enough to prove the concept and fuel Earth’s needs.

The blueprint borrows from Tesla’s robotics playbook: iterate fast, scale hard, and integrate vertically. Begin with SpaceX-style launch cadence, firing off payloads daily to build orbital factories by 2030, churning out solar panels from asteroid feedstock. Robotics, akin to Tesla’s Optimus, must mature into autonomous builders, assembling structures in microgravity by 2035. Energy tech, like wireless power, needs DARPA-like funding to leap from lab to orbit, hitting efficiency targets by 2040. Materials follow a Moore’s Law trajectory, doubling strength yearly until they’re Dyson-ready. AI orchestrates it all, optimizing orbits and maintenance, reaching maturity by 2045. This crash course leaves no room for error—every step must hit its mark, fueled by a wartime-scale budget and willpower.

Finishing by 2050 is a long shot, but not impossible. The physics checks out; the bottleneck is human ambition and execution. If we treat it as a species-level priority—ditching incrementalism for a moonshot mentality—we could see a skeletal Dyson swarm glowing faintly around the Sun, a testament to what we’re capable of when we stop dawdling and start building.