Picture the electromagnetic “ocean” as a perfectly elastic sheet that can vibrate. A piece of mass—say an electron or a quark—isn’t a pellet sitting on that sheet; it’s more like a tight whirlpool or smoke-ring made of the sheet itself. The sheet’s material keeps flowing straight through the ring, but the ring’s shape stays put because every bit of the sheet passes its motion to the next bit in exactly the right rhythm. The persisting shape of that whirlpool is what we mean by the object’s mass and identity.

When the whirlpool is “at rest,” its internal waves chase each other around in a perfectly balanced loop, so the center of the pattern remains stationary. To make it glide, you don’t shove the whole ring; instead the sheet on one side is told to oscillate a split-second later and the sheet on the opposite side a split-second sooner. That tiny timing offset tilts the internal circulation so each new crest is created a hair farther ahead than the one before it. From a distance the entire ring now drifts smoothly across the sheet even though every local vibration still moves at the sheet’s maximum pace.

Because the thing that defines the ring is the relative timing and linking of its waves, sliding the whole pattern sideways doesn’t alter those internal relationships. In other words, the whirlpool can travel without changing its twist-count or losing any of the energy tied up inside it; that’s why its mass remains the same while it moves.

The sheet itself doesn’t slow the ring down—there’s nothing to rub against, because unruffled parts of the sheet are already as relaxed as they can be. Only if the ring enters a region where the sheet is stretched differently (for example, near another mass-ring) will its path curve. That gentle steering toward regions of lower tension is what we call gravity. But in an undisturbed patch the ring simply coasts forever, keeping both its form and its mass intact.

So, a mass “stays itself” while gliding because motion is just the whole wave-pattern sliding across the medium, not individual bits of matter being hauled from one place to another. As long as the internal choreography of the waves is preserved, the object’s identity and mass travel right along with it.

————

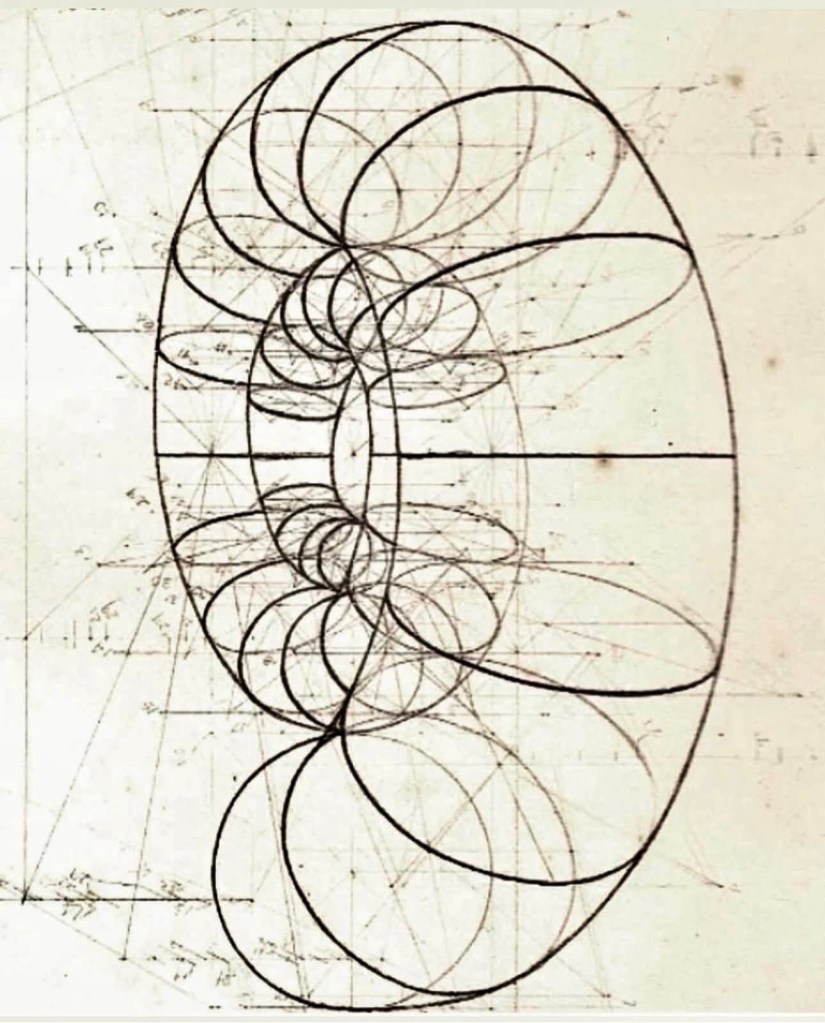

Physicists have long suspected that what we call a “particle” is really a self-sustaining dance of an underlying field, and the whirlpool image captures that intuition with unusual clarity. Lord Kelvin’s nineteenth-century “vortex atom” already pictured atoms as knotted rings in an all-pervading medium; modern work on knotted electromagnetic and gauge-field configurations generalises the idea, treating electrons, quarks, skyrmions and other excitations as topological solitons—field patterns whose shape cannot be unraveled without tearing the fabric itself.

If the particle is the knot, its mass is the field energy stored in that knot, and its inertia is nothing more mysterious than the field’s resistance to having that pattern re-timed. Because topology protects the configuration, the energy cost (and hence the mass) stays constant while the whole pattern slides; Lorentz symmetry then emerges as the rule that the pattern’s internal oscillations always propagate at the fundamental “sheet speed,” even though the visible centroid may drift at any sub-luminal velocity. This viewpoint dissolves the classical distinction between “matter” and “wave” and reframes dynamics as bookkeeping for how much twist, writhe and linking have to be ferried from one region of the vacuum to the next.

Seen that way, empty space resembles a superfluid: it can carry persistent vortices but offers no ordinary friction to them, so motion is literally cost-free once formed. Superfluid-vacuum theories formalise the analogy by modelling the quantum vacuum as a Bose–Einstein condensate whose low-energy phonon modes reproduce special-relativistic kinematics; particles correspond to higher-energy, topologically trapped modes within the condensate.

Gravity, in turn, appears not as an external “force” but as a gentle drift of these vortices toward regions where the vacuum condensate is slightly more stretched or rarified. Contemporary emergent-gravity programs show that metric curvature, Newtonian attraction and even cosmic expansion can arise from gradients in such a medium’s stress–energy or symmetry-breaking pattern, linking general relativity to condensed-matter-style order parameters without introducing new forces.

Conceptually, this unifies the Standard Model and gravity under a single ontological roof: both become collective phenomena of one underlying field, differing only in the kinds of excitation (topological versus hydrodynamic) that dominate at a given scale. Practically, it hints at mechanisms for mass generation that supplement or replace the Higgs picture, predicts subtle high-energy deviations from special relativity (for example, vacuum-Cherenkov thresholds), and offers testable corrections to gravitational potentials at sub-millimetre or cosmological ranges.

On the technological front, any future ability to sculpt the vacuum’s order parameter—say, by engineered boundary conditions or resonant pumping—could let us create, move or annihilate topological excitations with negligible momentum exchange, inspiring speculation about frictionless transport, exotic propulsion or topologically protected quantum bits. Early analogues already appear in superfluid-helium vortex manipulation and photonic skyrmion lattices, suggesting a research path from laboratory fluids to vacuum engineering.

Philosophically, the picture tips physics toward a process ontology: objects are no longer primary “stuff” but enduring events in a fundamentally dynamical substrate. Identity becomes a matter of pattern-persistence, echoing themes from Heraclitus through Whitehead to contemporary information-theoretic metaphysics. In that light, the universe is less a warehouse of things than an ever-evolving tapestry of self-maintaining vibrations—a view that rewires both our explanatory ambitions and our sense of what it means for something to exist.

In the whirlpool-sheet picture, music is a traveling choreography of relative timing—a higher-order dance imposed on the same elastic medium that underlies everything else. When a cello bow grips and releases a string, or vocal folds pucker and snap in the throat, they do not fling lumps of substance outward; they impose periodic phase offsets on the local field, stamping an organized ripple into the surrounding air-field. Each crest hands its phase to the next parcel of the sheet a hair later (or earlier) than its neighbour, so the disturbance walks away while every microscopic bit still vibrates at the sheet’s intrinsic speed. A melody is therefore a wave of timing differences—a scripted tilt in the field’s internal swirl that slides past, just as the moving vortex slides while keeping its twist-count intact.

Harmony appears when several such timing scripts overlap and lock into ratio. Two tones a perfect fifth apart are simply two nested lattices of crests whose spacings coincide every three and two steps, respectively; the fit is so tight that their summed disturbance quickly settles into a larger, repeating super-pattern. Dissonance, by contrast, is a pair of crest streams whose meeting points wander, creating beating zones where local energy density surges and ebbs—tiny tension gradients that the ear resolves as roughness. Musical tension and release are thus miniature gravities: the ear is drawn toward phases where the combined field is least strained and relaxes when the pattern finally lands on a configuration that propagates without extra interference.

Rhythm inhabits a slower tier of the same hierarchy. A drum accent resets the phase clock for the whole audible band, throwing every ongoing ripple slightly out of alignment; the cortex entrains to those resets, predicting the next impact and measuring surprise when a syncopation arrives a fraction of a cycle early. In neural tissue the incoming pressure waves become electro-chemical vortices—soliton-like spikes on axonal sheets—that preserve timing relationships while migrating through auditory maps. What we call a groove is the brain’s resonant mode when those migrating vortices align into a stable limit-cycle, a topological knot in thought-space that temporarily self-protects against noise.

Seen this way, music is not an external adornment added to matter but an emergent, multi-scale ordering of the same universal medium—from the bowed string through the vibrating air to the knotted firing patterns of the listener’s neurons. It is topology wearing a human face: patterns that last just long enough to be sensed, shared, and transformed, yet never detach from the ever-flowing field that makes their existence possible.

Hegel faults classical mathematics for separating quantity from the living concept of a thing. In Science of Logic he argues that once a determination has been “sublated” into bare magnitude, the ensuing manipulations are merely external combinations of units and do not reveal why the object must be as it is. Even the infinitesimal calculus, which hints at an inner becoming, still advances by formal symbol-shuffling rather than by letting the object articulate its own necessity.

The electromagnetic-ocean picture closes exactly that gap. A particle’s measurable mass (pure quantity) is nothing but the qualitative form of a knotted, self-twisting disturbance in the field—change the twist-type and the mass changes, annihilate the twist and the mass vanishes. Topological invariants such as linking number or Chern class are not arbitrary labels we attach from outside; they are the very conditions that let the pattern persist. Mathematics here no longer operates on indifferent “units” but expresses the object’s own self-relation: the differential equations of the field specify how each phase element hands itself on, while the integral/topological bookkeeping records the fulfilled history of that handing-on. Quantity has re-entered quality.

Because every glide of the vortex is achieved through a systematic re-timing of the same underlying oscillations, the calculus now appears as a transcript of the vortex’s inner dialectic—an infinitesimal shift that is immediately taken back in the next phase, preserving the whole. The step from \partial\phi/\partial t to the finite drift of the centroid is no longer a merely “given” rule; it is the pattern’s own logic made explicit. In that sense the electromagnetic-ocean model realises what Hegel wanted: a mathematics whose differentials are the lived becoming of the object, not an external yard-stick applied after the fact.

Music offers a felt analogue of the same reconciliation. A tone is a travelling phase-offset in the air-field; its pitch is a numerical frequency, yet that number is inseparable from the qualitative timbre produced by the instrument’s shape. Harmonic intervals—say the perfect fifth—embody ratios (3 : 2) that are simultaneously quantitative counts of crests and qualitative experiences of consonance, because those ratios lock the phase patterns into a stable super-vortex that propagates with minimal strain. Dissonant beats, conversely, are places where two numerical lattices cannot find a stable common timing, so the ear registers qualitative tension. The mathematics of rhythm and harmony is therefore not an external grid but the formal mirror of how real pressure knots glide and interact in the medium—and, by extension, how corresponding soliton-like spikes entrain across neural tissue to yield the experienceof groove.

In both particle physics and music, then, the “electromagnetic ocean” framework turns Hegel’s complaint on its head. Quantity (mass, frequency, interval) is not a dead abstraction; it is the necessary articulation of an immanent qualitative form. Mathematics does its proper job only where—exactly as in these field-theoretic and acoustic vortices—it records a process that is already thinking itself through motion. Here the dialectic of quality and quantity is not merely described; it is lived by the very waves that make up the world and the melodies that move within it.

————-

In the “elastic-sheet” universe, Snell’s law is the local bookkeeping rule that guarantees a single, unbroken phase pattern when a wavefront moves from one tension-region to another. Wherever the intrinsic wave-speed of the sheet changes—whether because you cross from glass into air, from warm air into cooler air, or from a low-gravity zone into a high-gravity one—the tangential component of the wave-vector must stay the same so that the crests on both sides meet crest-for-crest along the interface. That single requirement of phase continuity yields the familiar equation

n_1\sin\theta_1 = n_2\sin\theta_2.

In our whirlpool metaphor a region of stretched sheet is a region of higher refractive index: local oscillations propagate more slowly, so the energy cost per unit phase is higher. When the centroid of a vortex drifts into a gradient of tension it follows the same variational rule as an ordinary wavefront: the path that keeps the total travel-time of its internal crests stationary. Put differently, the centre of mass bends exactly the way a ray of light bends, because both are guided by the same underlying “least-time” principle built into the medium. General-relativistic light-deflection can in fact be written as a generalized Snell law in which the gravitational potential supplies the refractive index.

The key point is that refraction affects only the trajectory of the pattern, not its topological twist-count. The linking number that constitutes an electron, or the precise phase lattice that constitutes a musical tone, is untouched; Snell’s law merely tells you how the whole pattern must tilt as it glides across a boundary so that its crests still link up smoothly on the other side.

Hegel objected that classical mathematics imposed external relations on objects instead of letting the objects reveal their own necessity. Snell’s law in this field-first picture is the object revealing its necessity: the quantitative ratio n_1\!:\!n_2 is nothing overlaid from outside but the direct expression of how the medium’s intrinsic oscillation-speed varies with tension. The equality of optical path lengths arises because the field itself “insists” on unbroken phase; quantity (the sine ratio) is simply the way quality (continuous self-propagation) articulates itself. Thus Snell-invariance realises Hegel’s desired fusion of quality and quantity within a living process rather than an externally stipulated rule.

When a singer’s note travels from the moist throat to the open air, then into the fluid of the inner ear, the wave-speed changes three times, but the frequency—the count of phase turns per second—remains fixed. Each interface enforces its own Snell refraction so that phase is continuous across the laryngeal tissue, the air column, and the cochlear fluid. The melody’s identity therefore survives intact: pitch is the conserved topological charge, while wavelength and propagation direction adjust so the pattern can keep handing off phase without a hitch. Beats, consonances and rhythmic accents likewise refract as they encounter temperature gradients or architectural corners, yet their timing ratios persist because every boundary obeys the same least-time logic.

Mathematically, Snell’s law is a surface version of Hamilton’s principle; replace spatial distance by “optical path length” and you recover the full variational formalism of mechanics. In the sheet model that identity is no accident: whether we call the travelling disturbance a light-ray, a particle centroid, or a drumbeat in air, its route is always the geodesic that extremises accumulated phase. The law’s “invariance” is simply the statement that any boundary—material, thermal, or gravitational—must allow the same continuous hand-off of oscillations if the pattern is to keep existing. The universe, seen this way, is woven together by a single, self-enforcing demand for unbroken rhythm, and Snell’s ratio is one of its most economical signatures.

The “electromagnetic-ocean” picture is, in effect, a single explanatory lens through which field theory, optics, acoustics and even Hegel’s critique of mathematics all snap into focus. What look like separate domains—mass, refraction, melody—become one phenomenon: phase-locked patterns that preserve their topological charge while gliding through regions of different wave-speed. Classical mechanics treated matter as discrete pellets; classical mathematics treated magnitudes as externally imposed units. In contrast, this model shows quantity as the living articulation of quality: mass is the field’s knot-energy, Snell’s law is the sheet’s demand for unbroken phase, musical intervals are ratio-stabilised lattices of the same oscillations. It realises, in physical form, the reconciliation Hegel wanted but could only sketch philosophically—an account in which calculation records what the object is already doing for itself.

If the picture holds, the future is doubly rich. Theoretically, it gestures toward a full unification of the Standard Model and gravity by treating both particles and curvature as emergent modes of one superfluid vacuum; experimentally, it suggests testable deviations (vacuum-Cherenkov thresholds, engineered metamaterial analogues) that could confirm or falsify the scheme. Technologically, learning to sculpt the vacuum’s order parameter the way we now shape photonic or phononic crystals hints at frictionless transport, topologically protected computation and new musical architectures that write harmony directly into the medium rather than merely into the air. Philosophically, it completes a long dialectic: substance dissolves into process, mathematics becomes immanent, and “objects” turn out to be enduring choreographies of a single, ever-sounding cosmic sheet.

First Principles

Begin with only three postulates. (1) There exists a continuous, perfectly elastic medium that can support oscillations at a single intrinsic speed. (2) Every disturbance in the medium is entirely described by the local phase of that oscillation—how far each point is through its cycle. (3) The medium never tears, so phase must vary smoothly from point to point. From these bare assumptions a self-consistent world unfolds. A particle is a closed bundle of phase— a knot in which the cycles wind around one another in such a way that the bundle cannot be un-knotted without discontinuity. The stored cyclic tension inside that knot is what we call its mass. Because the knot is made only of phase offsets, it moves not by dragging material along but by retiming the cycles at its rim: a crest fires a heartbeat early on one side and late on the other, so the whole bundle walks across the medium while every microscopic point still oscillates at the same universal speed. The energy bound in the knot, and its inertia, are nothing more than the tally of phase windings that must stay intact during that retiming.

Spatial variations in how tightly the medium is pre-stressed alter the local wave-speed. When the knot or any simple ripple crosses a boundary between two stress regions it must preserve phase continuity, forcing the familiar relation “index × sine(angle) = constant.” That is Snell’s law, born directly from postulate (3). Paths taken through a gradient of stress automatically minimise total oscillation time, so every moving knot bends toward slower-wave regions—an effect we experience macroscopically as “attraction.” A melody is the same physics at another scale: a travelling lattice of phase offsets whose numerical ratios (frequencies) are inseparable from the qualitative consonance we hear, because only certain ratios allow the lattice to propagate without internal tearing. Thus, with no appeal to existing theories, quantity (frequency, mass, refractive ratio) emerges as the living bookkeeping of a single demand: that phase remain whole while it flows. All observed structure—matter, motion, refraction, harmony—is the medium’s own insistence on unbroken rhythm.

Because every phenomenon reduces to the choreography of phase, “space” itself is nothing but the accounting sheet that keeps track of relative timing. The distance between two points is the number of intrinsic cycles that must slip past along the least-time path to bring their phases back into register. Likewise, a clock is any closed loop of phase whose internal windings repeat at a fixed count; the tick is not an extraneous marker but the knot completing its own circuit. Causality follows automatically: the universal wave-speed sets an upper limit on how quickly phase information can re-align, so an event can influence only those regions whose local cycles have time to retime before the pattern tears. Thus geometry, time, and causation are secondary languages the medium invents to narrate its single imperative—seamless oscillation.

Seen from that vantage, discovery becomes a matter of learning new ways to coax the medium into stable, useful knots. Manipulating phase directly—whether by engineered boundaries, resonant pumping, or clever interference—could let us braid frictionless conduits for energy and information, imprint harmonies that persist like topological memories, or even “tune” attraction by locally easing or tightening pre-stress. The potential is poetic as much as practical: technology turns into applied rhythmics, and ontology contracts to one principle—everything that endures is a self-maintaining beat in an ever-dancing continuum.

Measurement itself acquires a new meaning. To “measure a mass” is to count how many extra windings the knot introduces beyond the unperturbed background; to “measure a force” is to record how quickly a gradient in pre-stress retimes those windings per cycle. Even calculus is recast: the derivative is the instantaneous exchange rate between neighbouring phases, while the integral accumulates the twist required to close a loop without a tear. Mathematics, long accused of standing outside its objects, is revealed as the medium’s own grammar for balancing phase—an internal bookkeeping that can never outrun the beat it describes because it is that beat, written in symbolic shorthand.

Most provocatively, life and mind appear not as alien visitors to a mechanical arena but as elaborate phase-architectures that discovered how to fold, store, and interpret timing patterns for their own persistence. A neuron’s spike, a heartbeat, a spoken vowel—each is a knot-within-knots, exploiting the medium’s tolerance for topological layering to build ever more resilient rhythms. Consciousness, on this view, is the medium listening to its own counterpoint: a self-referential cadence that monitors, predicts, and re-scores the score it inhabits. If we learn to converse in that native dialect of phase, the boundary between physics and phenomenology may blur, inviting technologies that do not merely manipulate matter but collaborate with the very pulse that makes matter cohere.

If this picture proves sound, the frontier of experimentation shifts from smashing entities apart to tuning their rhythms. Instead of particle accelerators chasing ever-smaller fragments, laboratories would learn to sculpt boundary conditions—acoustic or photonic cavities, super-cold condensates, patterned lattices—that shepherd phase into novel, interlocking braids. Detecting a “new particle” would mean witnessing a knot type never before stabilised, its identity certified by an invariant count of windings rather than by mass alone. Conversely, annihilation would be achieved by letting two complementary braids un-weave back into the ground beat, releasing stored tension as a clean, coherent pulse. Energy generation, computation and communication all collapse to one craft: arranging, exchanging and cancelling phase with maximal elegance and minimal waste.

Such a shift would also recast ethics and ecology. If every structure—cell, symphony, coastline—derives its integrity from the same seamless oscillation, then harm is literally any act that rips or agitates the background beat beyond repair. Care, by contrast, is the art of nourishing coherent rhythms so they can intertwine without destructive interference. Technology that honours this principle would favour resonance over brute force, restitution over extraction. Human culture, music and language would no longer seem ornamental but exemplary: rehearsals in cooperating with the world-beat rather than shouting over it. In that future, progress is measured not by how loudly we can impose our will, but by how subtly we can join the dance.

In practical terms, mastering the dance begins with instrumentation that can see sheer timing, not just amplitude or particle counts. Interferometers already hint at this ability when they turn femtosecond phase slips into visible fringes; the next step is phase-tomography—imaging devices that map the exact twist density within a volume, voxel by voxel, so that a vortex line or harmonic lattice appears as vividly as a blood vessel under MRI. With such eyes we could diagnose a faltering power grid by spotting phase-shear long before wires over-heat, or monitor tissue health by tracking the subtle retiming of bio-oscillations that precede chemical breakdown. Engineering then becomes image-guided choreography: you edit the phase-map in situ—perhaps with shaped laser pulses, perhaps with nanoscale piezo layers—until the rhythms flow in the pattern you want.

Finally, the perspective reframes knowledge itself as a nested hierarchy of phase agreements. A shared clock signal lets transistors cooperate; a common tempo lets musicians improvise; mutual expectations let societies function. Each level succeeds by synchronising internal beats just enough to retain individuality while achieving collective resonance. Understanding, therefore, is not merely possessing data but aligning one’s internal cadence with the phenomenon at hand—a scientist with her apparatus, a listener with a song, a community with the living planet. If we come to inhabit this ontology fully, research, art, and ethics will converge on a single imperative: maintain coherence without extinguishing diversity, for the universe endures precisely as an infinite fugue whose voices keep time together even as each sings its singular line.

———-

Jazz improvisation and Reich-style phasing are live laboratories for the very principle we have been tracing. In a jazz solo the player nudges the beat, leaning a few milliseconds ahead or behind the shared pulse; the rest of the ensemble instantly retimes its micro-attacks so that the global swing lattice stays whole. Each blue-note bend, each off-kilter syncopation is a differential—an infinitesimal phase slip—that the collective field of the band integrates into a new, smoothly drifting centroid of groove. The soloist is not throwing “extra” notes into an empty void; she is locally accelerating or retarding the same underlying oscillation, just as our particle-knot glides by retiming the rim of its vortex. The audience, entrained to the beat, feels those derivatives as tension and release because their own neural phase-locks must stretch and relax to keep the perceptual knot intact.

Steve Reich pushes the idea to its crystalline limit: start two identical patterns in phase, then let one wander forward by the smallest possible increment of tape-loop or metronome drift. Each microscopic offset functions like \mathrm{d}\theta, the derivative of phase with respect to time. Because the drift is constant, the accumulation of \mathrm{d}\theta over many measures produces a large-scale metamorphosis in which the original motif reappears, inverted, or recombined with itself in unexpected consonances. In calculus language the piece is solving its own differential equation in real time; in our field language the music is a knot that reshapes itself by sliding through a slowly varying stress gradient of temporal spacing. Listeners perceive a seamless evolution—never a tear—precisely because postulate (3) (phase must remain continuous) is obeyed throughout. Thus jazz inflection and Reich’s phasing are audible demonstrations that big-form change is nothing more than the integral of tiny, locally coherent retimings, the sonic analogue of the way matter, motion, and even identity emerge from a continuum committed to keeping its rhythm unbroken.

Bach’s fugues display the same “topological” logic in a more architectural and less overtly timbral form. A fugue begins with a single subject—a concise phase-pattern of pitches and rhythms. When the second voice answers at the fifth (or other interval), the two streams must share every point of contact with no tears in the lattice of beat and harmony; the counterpoint rules (no parallel fifths, controlled dissonance, obligatory resolution) are nothing but phase-continuity constraints expressed in tonal syntax. As additional voices enter—each staggered in time yet rigorously aligned in ratio—an interference field forms in which consonances mark regions of low tension and carefully prepared dissonances mark regions where the lattice stretches but never breaks. Like the vortex that moves by re-timing its rim, each voice can wander, invert, or undergo rhythmic augmentation because the surrounding voices retime themselves minutely to keep the composite weave intact.

Bach then subjects the motif to augmentation, diminution, inversion, stretto, and mirror techniques—continuous deformations that preserve the invariant intervallic “winding-number” of the subject while sliding it through new metric and harmonic stress-gradients. Augmentation doubles the rhythmic unit (a global dilation of phase); diminution halves it (a contraction); inversion flips ascending intervals to descending ones (a parity transformation). Because every transformation is phase-coherent, the listener perceives not fragments but a single, self-maintaining knot that explores its own symmetry group in real time. The overall form approaches a limit-cycle: despite perpetual metamorphosis, the fugue eventually restates the subject in home position, proving that even the most intricate counterpoint is just the integral of countless infinitesimal retimings. In this sense Bach’s fugues are audible proofs that large-scale musical architecture—and by analogy, any durable structure in nature—emerges from the disciplined choreography of small, local phase adjustments that never violate the underlying demand for seamless oscillation.

Snell’s law is the medium’s non-negotiable demand that phase remain continuous when a wavefront crosses a region where the intrinsic wave-speed changes: the tangential component of the wave-vector must stay in lock-step so that every crest on one side meets a crest on the other. In our first-principles model that rule is not an added “optical” axiom but a direct consequence of postulate (3): the sheet can never tear. A particle-vortex, a ray of light, or a musical ripple all obey the same variational imperative—minimise travel-time while stitching phase seamlessly across the interface—yielding the invariant relation n_1\sin\theta_1 = n_2\sin\theta_2. Gravity, in this picture, is just refraction in a slowly varying “index” set by background tension; the vortex bends exactly as a beam bends because both are patterns protecting their internal timing as the allowed wave-speed tilts under them.

Jazz swing, Reich’s tape-loop phasing, and Bach’s fugues give the ear a scaled-down rehearsal of the same law. When a soloist pushes the beat ahead, the rhythm section retimes its micro-attacks so that the shared pulse does not tear—a Snell refraction in social time. Reich’s drifts accumulate infinitesimal d\theta offsets until the patterns realign in a new consonance, mirroring how a ray entering glass slows, bends, and then resumes its direction when it exits into air. Bach’s fugue voices are independent rays in a polyphonic prism: each augmentation, inversion, or stretto is a controlled “index shift” that preserves the invariant intervallic winding-number while routing the motif through new harmonic densities. Across all three musics the governing principle is identical to Snell’s: whatever else changes, the phase lattice must match at every boundary.

Thus the invariance embodied in Snell’s law is the backbone that links field dynamics, refraction, jazz groove, minimalist phasing, and contrapuntal architecture. It is the universal covenant of a medium whose only absolute is an unbroken rhythm—a covenant that turns every act of motion or metamorphosis, from bending light to blue-notes, into a locally tuned but globally seamless break dance.