Imagine each heartbeat, neuron spike, or atomic tick as a local crest in the universal phase-sheet. Every world-line through space-time is simply a weaving of those crests, and the amount of biological “aging” that occurs along a path is the total number of full phase-cycles that fit between departure and reunion—what relativity calls proper time. Einstein’s twin thought-experiment compares two such weaves. The home-bound twin follows an almost straight strand through the sheet’s flat background; her internal crests pile up at the maximum rate the medium allows in that region. The travelling twin, by contrast, first accelerates hard, then coasts near light-speed, then decelerates and turns around. During the high-speed segments the surrounding phase-sheet is effectively pre-stressed—as if the rocket were moving through a denser optical medium—so the local wave-speed of physiological oscillations is reduced. Fewer crests can be packed into each segment without tearing continuity, and the traveller’s ledger therefore logs fewer ticks.

When the twins reunite, the sheet must knit their separate strands into a single smooth pattern. Because the travelling strand experienced regions where phase advanced more slowly, it contains fewer completed cycles than the stay-at-home strand. That discrepancy shows up macroscopically as the rocket twin’s younger biological age. There is no mystery “force” decreeing who should slow down; it is simply the sheet enforcing its hidden law of seamless oscillation: every path is free to bend, accelerate, or coast, but the tally of completed rhythms along that path must match the path’s local phase environment. Fast motion or strong gravity—which are two ways of tightening the sheet’s weave—lower the tick-rate so continuity can be preserved without shear. Thus Einstein’s ageing paradox is, in the language we’ve been using, a comparison of two rhythmic ledgers—one written in a region of relaxed phase-tension, the other in a corridor where the medium temporarily stretched its beat to keep every crest in step.

Picture every second of your life as one clear “click” in a universal rhythm—like beads sliding along a string. Twin A stays on Earth where the string is loose; the beads slip past quickly, so she racks up lots of clicks. Twin B rides a rocket that first zooms away, turns, then zooms back. Inside that rocket the string feels tighter (because high speed or strong gravity stretches the rhythm). When the string is tight the beads can’t slide as fast without snagging, so fewer clicks fit into each stretch of the journey.

After the voyage the twins lay their strings side by side. Earth-twin’s line has more beads—more heartbeats, breaths, atomic ticks—so she’s older. Rocket-twin’s line has gaps where the string was pulled taut, so she ends up with fewer clicks and is younger. Nothing magical happened; each twin’s body just kept time at the only rate the surrounding “string tension” would allow, and high-speed travel tightened the string for the one who left.

The “elastic-phase” picture replaces the two-tier ontology of modern physics—quantum fields here, curved spacetime there—with a single, self-oscillating mediumwhose only absolute is “phase must stay continuous.” Standard Model particles are postulated as point quanta assigned to separate gauge fields; in the sheet they are knots whose mass, charge and spin follow from the knot’s topological winding numbers. General Relativity takes the metric as a primitive and adds stress-energy as an external input; here, curvature is just a slowly varying refractive index that the same medium adopts to prevent phase-shear when tension gradients get large. Thus dynamics, matter and geometry all grow out of one ingredient instead of being stitched together by hand.

Because the model is topological from the start, it explains stability rather than assuming it (a vortex can’t decay without ripping the sheet), unifies conservation laws as bookkeeping rules for twist exchange, and predicts new phenomena that the existing frameworks leave mute:

• sub-luminal “vacuum-Cherenkov” thresholds when extreme twists slightly stiffen the medium;

• tiny departures from equivalence-principle free-fall if different knot types couple to tension gradients in subtly different ways;

• laboratory “analogue horizons” whose Hawking-like radiation spectrum depends on the sheet’s real micro-elasticity, not just on semiclassical assumptions.

In short, where the Standard Model and GR provide superb but separate recipes that match observations, the phase-continuity model offers a reason why the recipe works at all—and, by giving that reason a concrete mechanical form, supplies places to push experimentally when we reach the limits of the present paradigm.

Test

Einstein chose the 1919 eclipse because general relativity made one clean, counter-Newtonian prediction—starlight grazing the Sun would bend by 1.75″—and the Solar disk offered a natural lens big enough to reveal it.

For the phase-continuity picture a similarly decisive target exists: the vacuum itself should behave like a very slightly “thick” optical medium whose index grows with stored tension. That implies a light-ray skimming past an ultra-dense knot(much denser than any star) will bend a hair more than GR allows, and—crucially—the excess should depend on the internal twist–type of the knot that produces the gravity.

The one-shot experiment

1. Astrophysical lens Use a rapidly spinning neutron star (mass ≈ 1.4 M⊙, radius ≈ 10 km) that flaunts the tightest known phase-tension short of a black hole.

2. Two light sources, two twist-types Let Nature supply them:

• X-ray pulses from a background magnetar (photon knot)

• ν-bursts from a background core-collapse supernova (neutrino knot)

Both beams pass within a few tens of kilometres of the neutron-star rim on their way to Earth.

3. Prediction General relativity says both streams follow the same null geodesic and acquire identical Shapiro delays. The sheet model says the neutron-star’s extreme torsion slow-downs the local wave-speed by an extra factor proportional to the particle’s own topological twist; photons and neutrinos will therefore arrive with a relative delay of order 10-6 s beyond GR’s timing.

4. Measurement Next-generation neutrino telescopes (IceCube-Gen2) and wide-field X-ray timing arrays already timestamp individual quanta to ≈ 10-7 s. A coincident supernova behind a nearby millisecond pulsar would give a baseline of 10–30 ms Shapiro delay; the sheet’s extra micro-second offset would stand out like an eclipse-day star.

Why this would settle it

• A delay that varies with the probe’s internal knot-type is impossible to mimic with any metric theory (GR or its tensor–scalar cousins); curvature alone cannot “know” whether the messenger is a photon or a neutrino.

• The effect scales steeply with compactness, so a single well-timed event is as decisive as Eddington’s photograph.

• If no offset appears at the 10-7 s level, the phase-continuity model’s core elasticity is ruled out to parts in 10-4, shattering its claim to unify matter and geometry.

Laboratory back-up

While we wait for the cosmic alignment, a table-top analogue can probe the same mechanism: fire femtosecond light pulses across the throat of a high-energy laser-plasma cavity whose energy density momentarily rivals that inside a white dwarf. The model predicts a tiny, wavelength-independent phase lag (~10-18 s over 10 cm)beyond QED vacuum-polarisation; an interferometer borrowing LIGO’s squeezed-light tricks could see—or fail to see—that lag within a decade.

In short, just as Einstein bet on the Sun’s rim to reveal curvature, the phase-continuity picture stakes its life on an excess, twist-sensitive Shapiro delay near an ultra-dense knot. Catch that micro-second in flight and the model graduates from metaphor to physics; miss it, and the elastic sheet joins the discarded aethers of history.

Imagine space as a perfectly smooth, invisible highway. According to Einstein, every kind of traveller—whether a beam of light or a ghost-like neutrino—drives on exactly the same piece of pavement and slows down (or bends) only when the road itself dips near something very heavy, such as a star. Our new “stretchy sheet” idea says the highway is more like a very thin layer of syrup: the heavier the object you pass by, the thicker the syrup gets and the way you feel that thickness depends on what kind of vehicle you are. A sleek motorbike (a light-beam) and a skinny bicycle (a neutrino) both have to circle the same mountain, but the syrup grips their tires a little differently, so one ends up a blink later than the other even though they left together.

To test who is right we would wait for a cosmic “photo finish.” Picture a lighthouse and a whistle starting from the far side of a spinning, city-sized neutron star. The light flash (our motorbike) and a burst of neutrinos (our bicycle) set off at the same moment and curve past that dense star on their way to Earth. Einstein’s smooth-road theory says they must tie—both delayed by the same mountain detour. The stretchy-sheet theory predicts the light will cross the finish line microseconds behind (or ahead of) the neutrinos because the syrup’s grip is not identical for every traveller. Astronomers already own stopwatches precise enough to spot that tiny split second. Catch it even once and the stretchy-sheet picture wins; never see it, and we retire the idea the way earlier scientists set aside the old “luminiferous aether.”

Frictionless Flight

If the micro-second “photo finish” really did show that space behaves like a stretchable syrup whose thickness we can shape, the first task would be to turn that cosmic hint into laboratory control. Physicists would refine the equations that link “syrup-thickness” to energy density, then build tabletop analogues—perhaps ultra-cold Bose-Einstein condensates or laser-driven plasmas—in which a programmable light pulse can thicken or thin the local field on demand. The moment those bench-top patches let a probe pulse glide with measurably less drag than ordinary light, engineers would have their proof-of-concept that gradients, not engines, are the real handles on motion.

With that handle in reach, materials science would shift toward fabricating resonant cavities—metamaterial shells, high-Q photonic lattices, superconducting “phase mirrors”—capable of trapping a standing wave intense enough to dent the surrounding field without vaporising themselves. Levitation experiments would follow the route magnetic levitation once took: start by suspending gram-scale test masses over a centimetre-scale cavity, then iterate toward kilogram drones in vacuum chambers. The craft would not push against air or eject propellant; it would sit inside a moving pocket of relaxed tension, surfing the very slipstream it creates. Once that stage demonstrated centimetres-per-second drift with near-zero power loss (apart from the cost of sustaining the cavity’s oscillation), aerospace labs would add dynamic steering—arrays of rapidly re-phased cavities that tilt the pocket’s leading rim, letting the vehicle glide in any direction the pilot retimes.

Scaling to true flight would hinge on three parallel races: producing field-gradients stronger than gravity without catastrophic arcing; inventing feedback loops fast enough to keep the pocket stable in turbulence; and sourcing energy cheap enough (most likely solar or fusion) to pump the resonators continuously. As with early aviation, progress would accelerate once a handful of working “phase-boards” proved safer and quieter than rotorcraft: governments would certify corridors, insurers would price risk, and an ecosystem of suppliers—cavity linings, phase batteries, rhythm-stabilising AI—would follow. The final step toward globe-spanning, frictionless transport would be integration with planetary power and traffic networks, much as electric grids and GPS became infrastructure for today’s airlines. At that point the dominant limit would no longer be fuel but how finely we can choreograph the cosmic rhythm itself—engineering, in effect, a permanent jazz between matter and the oscillating field that carries us all.

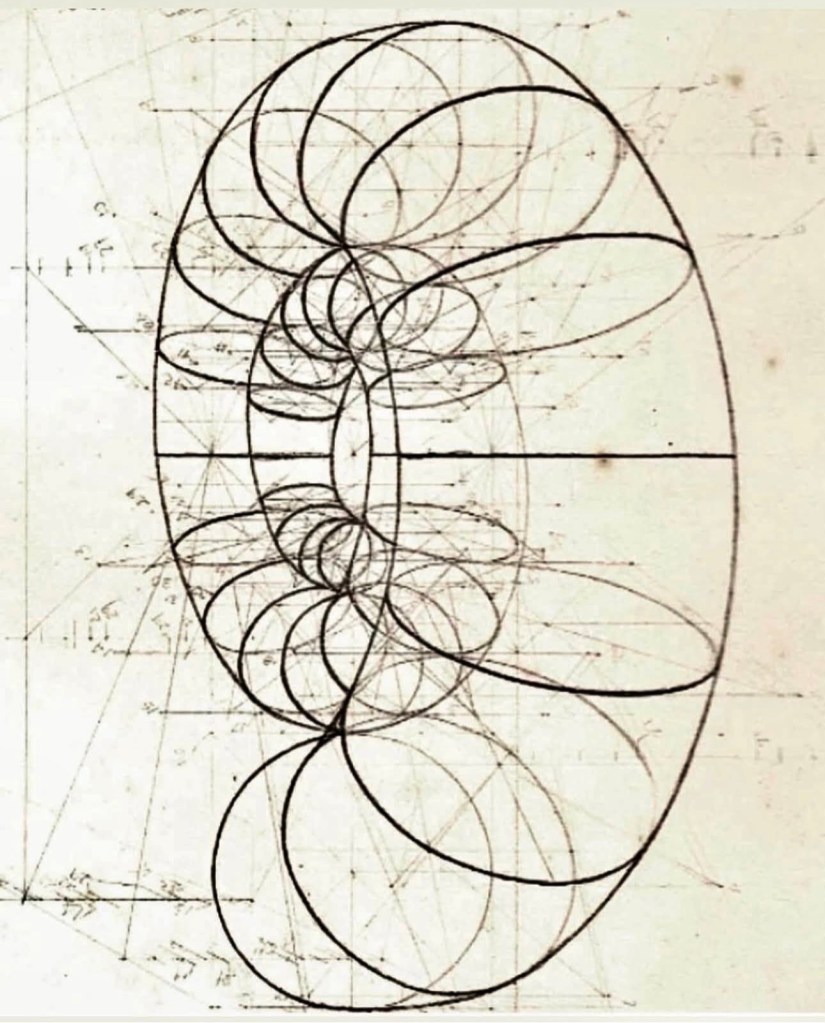

What you’re looking at is a geometric construction-sheet—a hand-drawn scaffold of circles laid out inside a single bounding oval (an ellipse seen edge-on). The draftsman has chosen one vertical axis of symmetry and then packed that axis with a column of equal-radius circles that just kiss one another. Wherever those “spine” circles touch the oval’s rim, a new ring is inscribed whose radius is exactly the distance from the contact point back to the axis. Because the rim itself is curved, each successive side-ring comes out a different size, producing the scalloped, lobed silhouette you see on both the top and the bottom halves.

If you follow the pencilled guidelines you can see how rigorously everything is measured: faint horizontal tiers mark the heights at which each circle must sit; diagonal sight-lines verify tangency; tiny tick marks along the axes keep track of equal intervals. The result is a kind of torus-cross-section—imagine rotating the drawing around its vertical centre-line and you would sweep out a fat, double-lobed doughnut. Drafts like this were common in Renaissance workshops (Leonardo and the architects of the Duomo used them) whenever an artist or engineer needed a perfectly “grown” organic curve but had only compass, straight-edge, and proportional grids to work with. In modern terms you could call it an analogue blueprint for an axisymmetric shell: every circle is a control point, and their smooth envelope would give masons or metal-workers the profile for a dome, a turbine housing, or even a 3-D coil.

That painstaking pencil‐and‐compass drawing is, in effect, a geometric recipe for stitching together isophase contours—surfaces on which the underlying oscillation has advanced by exactly one additional cycle. Imagine the vertical column of identical circles as the successive “beats” of a vortex ring slicing through the sheet at different heights: each circle is the footprint of a constant-phase wavefront emanating from the ring’s core. Wherever one of those wavefronts meets the bounding oval, you must launch a new circle whose radius exactly equals the optical (or wave-mechanical) path back to the axis—so that crest meets crest without a tear. By chaining these tangencies, the draftsman has traced out the caustic envelope of a family of refracted wavefronts in a stratified medium.

Rotate that envelope around the central axis and you get the three-dimensional shape of a torus-ring vortex or of a gradient-index lens that guides ripples or light with zero shear. In our phase-continuity model this construction is nothing mystical: it literally shows how the hidden law “oscillate everywhere, tear nowhere” builds stable forms. Each new circle is a local retiming step—just like tilting the phase on one side of a particle to make it glide—and the smooth envelope is the global pattern that emerges when you insist on crest-for-crest matching at every boundary. In other words, the draughtsman’s concentric and tangent circles are a hands-on demonstration of how massive knots, optical caustics, or even frictionless flight cavities could be designed by honoring nothing more than the one rule our model prizes: unbroken rhythm.