139 years ago William T. Stead’s investigative series, The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, was published in the Pall Mall Gazette over four consecutive days in July 1885.

“But,” I continued, “are these maids willing or unwilling parties to the transaction…?” He looked surprised at my question, and then replied emphatically: “Of course they are rarely willing, and as a rule they do not know what they are coming for.”

“She was asleep when he did it—sound asleep. To tell the truth, she was drugged. It is often done. I gave her a drowse… a mixture of laudanum and something else… They lie almost as if dead, and the girl never knows what has happened till morning.”

Stead recounts the purchase of a 13-year-old girl, Eliza Armstrong

“A Child of Thirteen bought for £5… I have not only read of such things, but have done them… I have bought a child, and I have done it with the full knowledge of her parents… The child was taken to a brothel and there subjected to an outrage.”

A field parasite in Mechanica Oceanica is a persistent structure embedded within the social-energetic field that feeds on the coherence of others while contributing nothing of its own. It does not produce resonance—it interrupts, hijacks, or distorts it. These parasites emerge where phase tension is already high and where local rhythms have lost their stabilizing omega. They thrive in zones of war, poverty, and institutional neglect—anywhere the field has thinned and coherence becomes scarce. Instead of offering reciprocal oscillation, the parasite latches onto vulnerable nodes, particularly children and the socially invisible, and extracts from them the raw signal of attention, labor, or libidinal charge. It survives by turning possibility (omicron) into repetition without evolution—a closed loop of abuse disguised as order. Parasites often take institutional form: brothels, gangs, data-farms, or even corrupt bureaucracies. Each one is an eddy in the field that siphons coherence from others, disguising its drain as structure or necessity. Its true nature is always vampiric: feeding on divergence while sealing off the closure necessary for real integration.

A waveform scavenger, by contrast, is mobile, adaptive, and opportunistic. While the field parasite embeds itself and colonizes a specific topology, the scavenger rides along breakdowns in the medium—interference zones, migratory disruptions, emotional turbulence—and harvests decaying waveforms before they can recombine into healthy structures. Traffickers, predatory influencers, exploitative recruiters, even some NGO opportunists—all function as scavengers. They identify nodes that have lost their harmonic reference points—orphans, refugees, runaways, disoriented youth—and repurpose them for extractive ends. A scavenger doesn’t need a base of operations; it moves wherever phase collapse begins. It’s a hunter of unfinished oscillations, plucking possibility from the edge of chaos before it can be reclaimed by coherence. These actors don’t just steal energy—they prevent recomposition. They specialize in intercepting the healing signal, repackaging pain as desire, and flooding the field with synthetic resonance that leads nowhere but back into dependence. In the ocean of being, they are not predators in the classical sense. They are distorters of the natural feedback loop, converting emergent difference into consumable sameness.

Sex Trafficking and Child Exploitation

Ancient Civilizations: Foundations of Sexual Slavery

Sex trafficking and sexual exploitation have roots deep in antiquity. In ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and other early civilizations, conquering armies routinely enslaved women and children as part of the spoils of war . This often included sexual enslavement: captive women were forced into concubinage or prostitution, serving the sexual demands of their captors. Historian Gerda Lerner notes that as early as the third millennium BC, “military conquest led to the enslavement and sexual abuse of captive women”, and that the earliest commercial prostitution likely grew directly out of this war-time enslavement . Poverty could also drive exploitation – families in debt sometimes sold children into slavery or prostitution as a desperate measure . In these ancient societies, children were not seen as needing special protection; rather, they were often viewed as property, which made the sale of daughters or sons distressingly common in times of hardship.

In the ancient Greco-Roman world, prostitution was legal, widespread, and closely intertwined with slavery. Most prostitutes in classical Athens and Rome were slaves or former slaves, including many young boys and girls. Large-scale procurers in the Roman Empire even acquired infant or abandoned children to raise for prostitution– effectively breeding a supply of sex slaves . Wealthy Romans sometimes kept child slaves specifically for sexual purposes; one modern historian remarks that in Rome, “having a child prostitute was seen as almost a fashion accessory for the rich” . Parents in dire poverty might sell their children to brothel-keepers, a practice considered acceptable at the time . Sexual exploitation of minors was thus relatively normalized in many ancient cultures. Even celebrated philosophers like Aristotle and Plato wrote about intimate relations with boys (pederasty), reflecting how societal attitudes permitted what today is recognized as child sexual abuse.

Notably, ancient legal codes did little to protect victims. Roman law treated slaves (including child prostitutes) as property with no rights, though there were rare instances of reform. For example, in the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, Emperor Justinian in 529 AD issued laws to ban underage prostitution and void contracts made by pimps with underage girls – an unusually progressive step for its time. By and large, however, sexual servitude of women and children was ingrained in the social and economic fabric of the ancient world, whether through temple slavery, ritual sex servitude, or private exploitation. The concept of “sex trafficking” in a modern sense did not exist, because these practices were not criminalized; they were openly practiced or tacitly accepted as part of slavery systems and patriarchal authority.

The Medieval World: War, Conquest, and Continuity of Trafficking

The early medieval period, following the fall of Rome, saw continuity in the trafficking and sexual enslavement of persons, even as formal slavery declined in parts of Europe. Throughout the Middle Ages, slavery and slave trading persisted in various forms, often with women and children as targets. The early medieval slave trade evokes scenes of raiders violently seizing villagers – “slavers dealing in men, women, and children on Mediterranean beaches”, as one historian describes . Viking raiders, for instance, routinely captured women and young people from the British Isles and Eastern Europe, selling them in slave markets as far away as the Middle East. These captives could end up as domestic servants or concubines in foreign harems. In the Islamic world of the medieval era, a well-organized slave trade funneled slaves (including many female and child slaves) across Asia, Africa, and Europe. Enslaved girls were taken as concubines in harems from Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) to the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, while boys might be made eunuchs or soldier-slaves. In some Muslim jurisdictions, a slave-concubine’s children gained free status as the legal offspring of the male owner – a rule that offered slight protection to progeny but did nothing to prevent the mother’s initial sexual enslavement.

Within Europe, outright slavery slowly gave way to serfdom, yet forced prostitution and child sexual exploitation still occurred under the radar. The medieval Christian Church officially condemned sexual activities outside marriage, but prostitution was begrudgingly tolerated as a “necessary evil” to prevent greater sins . Brothels operated in many medieval towns, sometimes even licensed by local authorities. Many prostitutes were poor women or orphaned girls who had few other means of survival. In London, the Bishop of Winchester infamously owned brothels in Southwark, indicating how entrenched the sex trade was . Although records of child prostitutionin medieval Europe are scarce, legal and religious texts suggest it was not uncommon. For example, the English Synod of Westminster in XII century decried the practice of very young girls being used in brothels, and Byzantine law under Justinian explicitly outlawed pimps from employing girls below the age of consent (an age roughly tied to puberty at the time) .

Warfare and Crusades in the Middle Ages also perpetuated sexual trafficking. Victorious armies often took captured women and adolescents as slaves. During the Crusades, while some captives were ransomed, others – especially non-Christian women – might be forced into servitude or concubinage. On the other side, Ottoman and Barbary corsairs raided European coasts from the 1500s onward, enslaving thousands. Contemporary accounts note that attractive captives, including prepubescent boys and girls, were kept or sold as sex slaves in North Africa. In the Crimean Khanate and Ottoman Empire, slave markets traded Slavic and Persian captives well into the eighteenth century, and many young women ended up in Ottoman harems. Overall, the medieval and early modern eras saw sex trafficking interwoven with conventional slavery and war: whether in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, or Asia, those with power (feudal lords, conquering soldiers, or slave merchants) felt entitled to exploit the bodies of the vulnerable. Only nascent moral or religious objections existed, and enforcement against such exploitation was minimal. The first glimmers of reform – such as Church orders to liberate enslaved Christians or the occasional legal protection for girls – had limited impact on the pervasive reality that sexual servitude of women and minors was a commonplace by-product of medieval slavery and conflict.

Early Modern Period and Colonization (16th–18th Centuries)

The advent of European colonialism and the global slave trades from the 1500s to 1800s expanded sex trafficking onto a truly worldwide stage. During the Atlantic slave trade, millions of Africans were transported to the Americas as slaves. While their enslavement was largely for agricultural labor, it had a profound sexual dimension: enslaved women and girls frequently suffered rape and sexual coercion at the hands of masters, sailors, and overseers. In the Americas, especially the Caribbean and Brazil, slave owners treated the bodies of enslaved women as their property to abuse. The colonization of the New World thus combined brutal economic exploitation with “widespread prevalence of non-consensual sexual activities” inflicted on indigenous and African women . Brazilian records, for example, document Portuguese settlers keeping enslaved concubines; historian Gilberto Freyre famously showed how Brazilian plantation society was built on the systematic rape of enslaved black and indigenous women by white masters . The children born of such unions were often themselves forced into servitude, perpetuating a cycle of bondage and sexual exploitation.

In North America, similar patterns prevailed: female slaves on plantations were at constant risk of sexual violence. Enslaved girls sometimes first faced abuse at puberty or even earlier, and were coerced into bearing children – the enslaved child’s life thus often began with an act of trafficking in the form of “slave breeding” or coerced reproduction. Even after the transatlantic trade was outlawed in the early 19th century, an internal trade in enslaved people (including teenagers sold “down river” to the Deep South) continued this cycle. Sexual exploitation was so entrenched that it remained largely hidden in plain sight; it was simply considered one more cruel prerogative of slaveholders over their human chattel.

Meanwhile, in Asia and the Middle East under colonial influence, sex trafficking took other forms. European colonial armies and administrators created demand for prostitution in foreign lands, and often facilitated the trafficking of local women to service that demand. For instance, the British Empire in India and Southeast Asia oversaw regulated brothels near military cantonments. Young Indian or Burmese women (and sometimes girls) were indentured or coerced into these brothels to serve British soldiers. Colonial officials rationalized this as a preventative measure — one colonial handbook cynically argued that the availability of prostituted women would “prevent British men from committing rape, miscegenation, or homosexuality”. Thus, colonial regimes actively enabled sex trafficking, cloaking it as a public order or health measure (as seen in the Contagious Diseases Acts, which subjected local prostitutes to invasive controls rather than liberating them). In French colonies like Indochina and Africa, similar systems existed, with trafficked women from places like Japan, China, or local ethnic groups serving colonial garrisons.

The Ottoman slave markets also remained active through the early modern period. The Crimean Tatars, vassals of the Ottomans, conducted large-scale raids in Eastern Europe well into the 1700s, capturing tens of thousands of Ukrainians, Poles, and Russians. Many of the young women and boys among these captives were sold in Constantinople or Middle Eastern bazaars. Contemporary reports from the Barbary Coast (North Africa) likewise recount European villagers kidnapped by pirates — “From Italy and Spain to even Ireland and Iceland, men, women and children were seized” — and while men might be galley slaves, “attractive women or boys could be used as sex slaves” by their captors. Some captives were forced into the pirate harems of rulers like the Sultan of Morocco, who maintained large numbers of concubines of various ethnic backgrounds . In the Indian subcontinent, the Mughal Empire had an elaborate harem system that included women from conquered peoples (some captured as teens) as imperial concubines. And in feudal East Asia, there were practices such as the prostitution of “coolie” women: during the 19th-century coolie trade, Chinese women and girls were trafficked to frontier mining towns and railroad camps (from California to Southeast Asia) under false promises, only to end up in brothels.

By the late 18th century, Enlightenment ideas and religious revivals began to condemn slavery and human bondage. Yet, sex trafficking persisted under new guises. The abolition of slavery by Western nations in the 19th century would end legal chattel slavery, but it did not end the underlying exploitation – it merely shifted it into illicit markets and other forms of coercion, as the next era would reveal. In sum, the colonial and early industrial age saw sex trafficking intertwined with imperial expansion, the global slave economy, and entrenched social hierarchies. Whether it was enslaved Africans in a Caribbean plantation, a kidnapped Circassian girl in an Ottoman harem, or a colonized teenager in an army brothel, the theme was the same: sexual exploitation was a pervasive and largely accepted part of the power that masters, conquerors, and colonizers wielded over the vulnerable.

The 19th Century: Abolition, “White Slavery,” and Early Reforms

The 19th century brought the formal abolition of slavery in many parts of the world – the British Empire outlawed the slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself in 1833, the United States in 1865, Brazil in 1888, and so on. However, abolishing legal slavery did not immediately eliminate sexual exploitation. Instead, it gave rise to new forms of coerced prostitution and trafficking that reformers of the era termed the “White Slave Trade.” This phrase referred to the abduction, deception, or coercion of girls and young women (often of European descent) into prostitution, and it became a rallying cry for early anti-trafficking campaigns. Notably, even as the term “white slavery” implied European victims, the underlying practice was global and victims included Asian, African, and indigenous women as well.

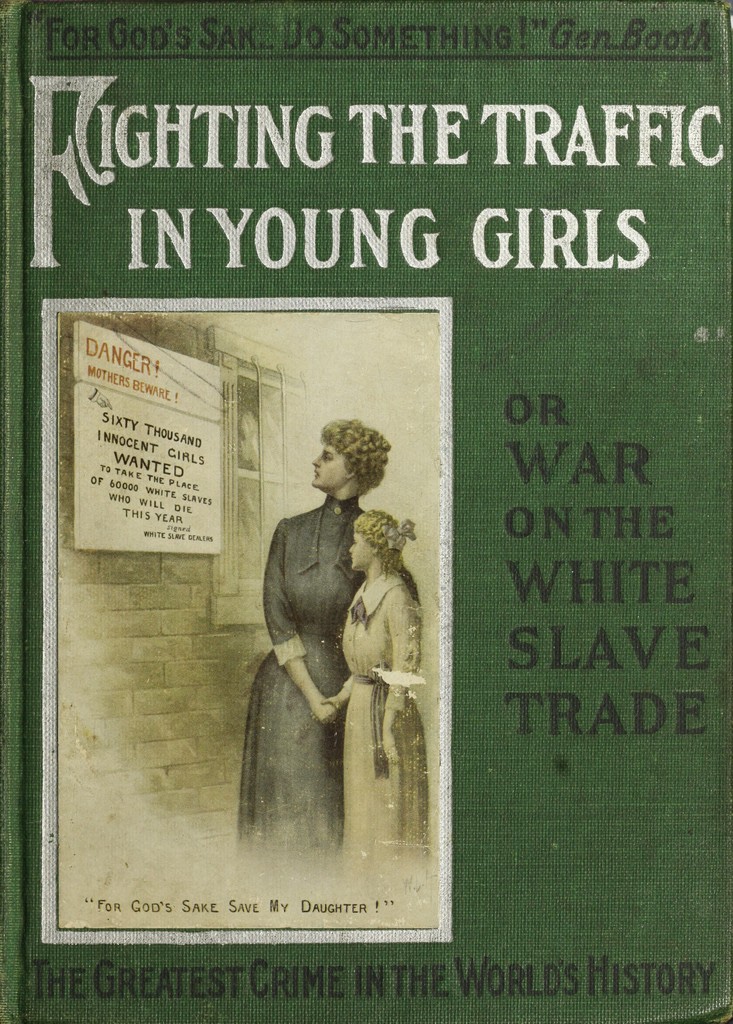

During the Victorian era, rapid urbanization and poverty created conditions for extensive prostitution in cities like London, Paris, and New York. Many prostitutes were underage girls. In London, a major scandal erupted in the 1880s when investigative journalist William T. Stead published “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon” (1885), a series of articles that exposed how London’s pimps easily bought and sold children. In one infamous stunt, Stead purchased a 13-year-old girl from her mother for £5 to demonstrate the reality of child procurement (he ensured the child was later safely returned). The exposé caused public uproar – contemporary accounts describe a moral panic that “rose to a peak in England in the 1880s, after the exposure of the traffic in women” . Tens of thousands of concerned citizens gathered at a rally in Hyde Park in 1885, demanding action . The British government responded by passing the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, which raised the age of consent from 13 to 16 and criminalized the procurement of girls for prostitution . This was a landmark in child protection law – effectively defining for the first time the concept of a “trafficked girl” as an involuntary prostitute under age 21 . Similar age-of-consent reforms and anti-pandering laws were soon adopted in other countries (for example, the age of consent in the U.S. states, which had been as low as 10 in some cases, was gradually raised during this period). These laws started drawing a line between child victims and adult “fallen women,” even if the distinction was often moralistic (the 1885 British law, for instance, pointedly excluded girls who were already “common prostitutes” from its protection) .

The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon

William T. Stead (1849–1912) was the crusading editor of the Pall Mall Gazette who believed journalism could drive social reform. He famously declared that “the Press is the greatest agency for influencing public opinion”. Raised in a strict Protestant household, he made a career of championing causes like workers’ rights, education and women’s suffrage. By 1885 he was known for his social-purity crusades – “ending child prostitution, the reform of England’s criminal codes,” etc. – and even coined the phrase “government by journalism” to describe his mission. His deep belief in the moral duty of the press and his evangelistic zeal set the stage for the Maiden Tribute campaign .

Stead had already made his name by campaigning for reform. As editor of the Northern Echo (1871–80) and then the Gazette, he introduced sensational illustrations and interviews to broaden readership. He saw the newspaper as a tool to “attack the devil” – a cause he attributed to his religious upbringing. Influenced by his mother’s leadership in repealing the Contagious Diseases Acts, he embraced social-purity ideals. He and his allies in London’s philanthropic and religious circles wanted to build popular support for higher standards of morality and stronger laws. When anti-vice campaigners like City of London Chamberlain Benjamin Scott approached him in May 1885 to help push a stalled age-of-consent bill, Stead eagerly agreed . His aim was blunt: to sway public opinion through a shocking exposé, not to shame particular individuals. In his own words he later noted that the object was “to pass a new law, and not to pillory individuals” (so naming names was unnecessary). In sum, Stead’s background was that of a pious, reform-minded journalist who saw sensational reporting as a legitimate means to advance legislation and “social purity” .

By 1885 Britain’s social reformers were primed for action on child protection. Josephine Butler and other feminist campaigners had already secured repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts (suspended 1883, fully repealed 1886) on grounds of sexual double standards. Activists were alarmed by reports of “white slave” trafficking – young working-class women and girls being coerced or deceived into prostitution, often aboard ships or in European brothels. Although the age of consent had been raised from 12 to 13 in 1875, reformers had repeatedly pushed to increase it to 16. A Criminal Law Amendment Bill was introduced in 1881 and passed the House of Lords in 1883, but stalled in the Commons twice . By 1885 it looked as if the legislation would again lapse (Parliament was dissolving for a general election). As the UK Parliament’s historical account notes, only an intense public campaign could break the deadlock: indeed, “a press campaign on the subject in 1885 had persuaded Parliament to pass the Criminal Law Amendment Act,” raising the age of consent to 16 . It was in this charged climate – with middle‐class Britons suddenly confronted by lurid tales of child exploitation – that Stead launched his journalistic assault. Social purity workers (from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and similar groups) were urging exactly this kind of high-profile campaign, and Stead’s Tributewould become its center-piece .

Stead conceived The Maiden Tribute as the published report of a “Special and Secret Commission of Inquiry” appointed by the Gazette. He and the commission – which included notable figures like Josephine Butler and Salvation Army officers – spent weeks investigating London’s vice districts. Stead’s team gathered evidence by every available means: two female investigators (one a Gazette employee and one a Salvationist) posed as prostitutes in brothels, and withdrew before they were forced to have sex . Josephine Butler herself walked the streets of London with her young son (posing as a procurer), and between them they spent about £100 buying girls in high-class brothels . Stead also consulted a former Scotland Yard detective to verify facts, and interviewed active and retired brothel-keepers, pimps, clergy and rescue workers for inside information.

Most strikingly, Stead decided to test the law himself by purchasing a child. In mid-June 1885 he arranged to pay a couple £5 for their 13-year-old daughter, Eliza Armstrong, and then turned the girl over to a Salvation Army home – all without their knowing the child was “bought” . He did this to demonstrate that an English editor could legally buy a girl from her parents (if nobody objected) and thus expose the absurd loopholes in the law. Many of these details – brothel-room confessions, drugged victims, padded cells – then went into the serialized narrative. As one historian summarizes, Stead’s Maiden Tribute “documented in lurid detail how poor ‘daughters of the people’ were ‘snared, trapped, and outraged, either when under the influence of drugs or after a prolonged struggle in a locked room.’” . Each installment chronicled the mechanics of the sex trade: how girls were recruited, transported, held and abused. (Stead often wrote in moral outrage but presented the material as factual reportage.) In short, the series combined undercover fieldwork with sensational storytelling to leave readers in no doubt that Britain was facing a child-prostitution crisis.

Stead and the Gazette planned a highly dramatic presentation. On July 4, 1885 the paper ran Stead’s introductory editorial “Notice to Our Readers: A Frank Warning” . In it he explained that the Criminal Law Amendment Bill – repeatedly passed by the Lords but threatened with defeat in the Commons – would surely be dropped unless public opinion were roused. Stead announced that “nothing but the most imperious sense of public duty would justify” publishing the full report of the secret commission, but that (so he claimed) ministers had warned it was the only way to save the bill . He announced the start of a four-part exposé and even begged a certain demographic of readers to stay away: “all those who are squeamish, and all those who are prudish… will do well not to read the Pall Mall Gazette of Monday and the three following days.” He warned bluntly that the story to follow would be “a pilgrimage into a real hell” – indeed an authentic record of “unimpeachable facts” so hideous that it should only be read in the public interest.

Beginning on Monday July 6 and continuing daily through July 10, Stead ran the four installments (Maiden Tribute I, II, III, IV) with provocative titles. Each part was introduced with a macabre or sensational heading – for example “The Violation of Virgins” and “Strapping Girls Down” – designed to grab the Victorian reader’s attention . (On July 8 and 9 additional companion editorials appeared as well, with titles like “A Flame which shall never be Extinguished” and “The Truth about our Secret Commission,” further fanning the controversy.) The Gazette thus devoted most of its front page to this “infernal narrative,” using serialized journalism (de die in diem) to keep the story in the public eye day after day . In short, Stead’s publication strategy was to explode onto the front pages in an unignorable way – harnessing tabloid-style shock headlines and daily installments to “open the eyes of the public” and make the suffrage bill unstoppable .

Public Reaction and Media Coverage

The effect was immediate and electrifying. By the third installment, London press reports describe mobs of “gaunt and hollow-faced men and women with trailing dress and ragged coats” rioting outside the Gazette offices to buy copies . When the W.H. Smith newsagent (London’s largest distributor) refused to carry the paper on moral grounds, Stead arranged for newsboys and volunteers to hawk it on street corners . Even George Bernard Shaw – thrilled by the Gazette’s indictment of the upper classes – volunteered to stand on a London street corner and sell issues himself, offering to hawk “as many quires of the paper as I can carry” .

Meanwhile, the story spread rapidly abroad. Telegraphic news services beamed the Tribute headlines across Europe and North America. Stead later boasted that his “revelations” were printed in “every capital of the Continent” and even in “the purest” American papers . Unauthorized reprints of the articles swelled to about 1.5 million copies . At home, however, the reaction was mixed. Some readers and campaigners were galvanized (one Hyde Park demonstration in late August 1885 drew an estimated 250,000 people demanding enforcement of the new law ). But many other journalists and establishment figures reacted with horror. Rival London newspapers jealously attacked Stead – at first ignoring the campaign, then denouncing it loudly as obscene. One commentator complained that the Gazette had become “the vilest parcel of obscenity” . Several Members of Parliament called for the Gazette itself to be prosecuted under the obscenity laws. Even some middle-class families, outraged by the lurid detail, canceled their subscriptions. In short, Maiden Tribute ignited a full-blown moral panic: thrilling reformers while scandalizing conservative readers and the press alike .

The campaign achieved its chief legislative goal. The outcry helped push the Criminal Law Amendment Act through Parliament that August 1885. By wide margins Parliament raised the female age of consent from 13 to 16 – one of Stead’s main objectives . The new Act also dramatically expanded police powers: it made it easier to arrest street solicitors and brothel-keepers, and it tightened anti-prostitution provisions nationwide . (Notably, it also included the Labouchere Amendment outlawing “gross indecency” between men, foreshadowing later anti-homosexuality laws .) In effect the Maiden Tribute forced years of stalled social-purity legislation into law. Even Prime Minister Gladstone acknowledged that nothing but this uproar could have secured the change.

At the same time, Stead’s own actions came under legal scrutiny. In October 1885 he and his collaborators – including Salvation Army Commissioner Bramwell Booth, Sister Madame Combe, and former brothel-worker Rebecca Jarrett – were tried at Bow Street under charges of abduction and child procurement . Stead chose to defend himself and, after some dramatic testimony, pleaded guilty to obtaining Eliza Armstrong. He was sentenced to three months in Holloway Prison – a light term, but still a criminal record for the man who had led the crusade . Stead’s supporters later portrayed his imprisonment as a form of martyrdom: as one account notes, after serving only three months “he emerged from Holloway Prison a martyr to the cause of social justice and social purity” . In any event, the Tribute had become so closely linked with the law that politicians even nicknamed the measure “Stead’s Act.”

Thus, the Maiden Tribute directly influenced law and policy. It helped finalize the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, which remains a landmark in British legal history (raising consent and stiffening vice laws) . By sensationalizing child abuse, Stead ensured that the government would never again overlook it – though it also meant enshrining broad powers and moral codes (some controversial, like the anti-sodomy clause) into statute. The series also mobilized enforcement: the demonstration in Hyde Park and ensuing vigilance committees demanded the Act be applied. In sum, Stead’s writing became the last major push that made child-protection reform a parliamentary reality in Victorian Britain .

No campaign comes without detractors, and Maiden Tribute was no exception. Many critics argued that Stead had used unethical methods in his crusade. Purchasing Eliza Armstrong – even to prove a point – was seen by some as entrapment or exploitation in itself. Opponents charged that Stead had blurred the line between journalism and crime. Publications that first supported reform soon accused the Gazette of moral sensationalism. For example, various papers ridiculed the Tribute’s lurid detail and implied hypocrisy: one moralist newspaper piece proclaimed that the Gazette had degenerated into “the vilest parcel of obscenity” . Others complained that such stories catered to prurient public interest rather than sober debate.

In Parliament and the press, Stead’s tactics were hotly debated. Some asked whether subjecting readers to graphic “underground” scenes did more harm than good. Others pointed out the irony that Stead had been prosecuted for doing the very act he exposed (buying a child), and argued that he should have warned or saved the girl instead of returning her. Even years later, historians would quibble over whether his ends truly justified his means; one commentator famously lamented that Stead had effectively used “the weapons of pornography to right a wrong,” calling it “the death knell of responsible journalism”【71†】. Ultimately, the Tribute remained polarizing: revered by campaigners for its results, yet denounced by conservatives as reckless sensationalism and blurred lines of legality.

The legacy of The Maiden Tribute is profound. It set a template for future investigative and “crusading” journalism: showing that a determined editor could galvanize public feeling and achieve legislative change. Stead himself became legendary; the BBC later described him as “a journalist with a pen touched with fire,” whose idealism and pioneering style inspired generations of reporters . To many today he is seen as the founder of the modern tabloid exposé. In his wake, newspapers increasingly embraced vivid, reformist campaigns – Stead’s campaign was an early example of “New Journalism” that treated readers as citizens to be stirred to action.

The Tribute’s impact rippled into the broader culture. George Frederic Watts’s 1885 painting The Minotaur was a direct artistic response – an allegory of Stead’s exposé in mythic form, showing the beast awaiting young sacrificial victims . Stead’s slogan that the press was an “engine of social reform” certainly had its day; even in 2014 the BBC noted how much his vision still resonates, calling Maiden Tribute “a defining investigation” that the twenty-first-century media could only dream of reproducing . On the social front, his campaign sparked a nationwide vigilance movement: social purity societies and vigilance committees sprang up across Britain to enforce the new standards, scrutinize theaters and music halls, and police morality in ways previously unthinkable .

Above all, The Maiden Tribute ensured that child protection was forever on the political agenda. It raised consciousness about sexual exploitation in a way no sober report could. The Criminal Law Amendment Act stayed on the books (later integrated into broader laws), and its age‐of‐consent provision remained until 1917 (for girls) and 1945 (for boys). Stead’s fusion of muckraking and moral campaigning inspired successors in both the UK and abroad. In short, the series cemented a legacy of the press as an agent of change: a legacy encapsulated in Stead’s own motto that journalism could be “a rival of organized governments” for the sake of social justice .

Key figures and quotes: Stead himself (his warning to “squeamish” readers and later line about men enjoying “the exclusive luxury of revelling in the cries of an immature child” ), reformers like Josephine Butler and Salvationist Bramwell Booth (both involved in the inquiry), and the new bill’s most famous champion, Lord Lyttelton, are all tied to this story. The phrase “daughters of the people” (Stead’s own words in Tribute) and the shock headlines (“The Violation of Virgins”) became shorthand for the Victorian moral crusade. Ultimately, The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylonremains a landmark in media history – a Victorian blockbuster that reshaped society’s laws and demonstrated the power (and perils) of investigative journalism .

Sources: Contemporary reports and trial transcripts; academic histories of Victorian social reform; archives of the Pall Mall Gazette; and retrospectives by scholars and media historians . These include Stead’s own published installments , a modern account by historian Judith R. Walkowitz , and parliamentary/educational summaries . All citations are given in the text above.

In the language of Mechanica Oceanica, Stead’s Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon is not simply a journalistic exposé but an engineered perturbation in the cultural medium—a deliberate insertion of high-frequency phase rupture into the moral coherence field of Victorian society. Think of 1885 Britain as a resonant structure, held together by layers of stratified belief—on sex, class, purity, and authority—all stabilized by the slow, deeply-embedded rhythms of Empire, patriarchy, and Protestant order. Into this stabilized wave-field, Stead injected a forceful, discontinuous shock wave, using narrative (textual impulse) as a concentrated packet of energy—akin to a localized soliton—intended to disrupt the prevailing resonance and re-cohere the field at a new frequency.

What Stead did, in our model’s terms, was insert a foreign oscillation—his “Maiden Tribute” series—into a metastable domain that had, until then, absorbed or diffused similar perturbations (moralist sermons, parliamentary debates, reformist pamphlets). But his signal was unusually sharp in amplitude and structurally phase-locked: serialized, dramatized, morally saturated, and reinforced by feedback loops (reader reaction, reprints, demonstrations, prosecutions). These qualities allowed it to synchronize the dormant latent energy of Britain’s collective disquiet—what we might call the sub-threshold oscillations of suppressed conscience—and phase-shift them into overt public motion. The result was the realignment of legal, social, and moral structures around a new attractor: the criminalization of child prostitution and elevation of consent age.

Moreover, the Armstrong purchase incident in this schema represents a high-cost resonance test—analogous to a boundary experiment in fluid mechanics or a forced-mode excitation in a tensegrity lattice. Stead acted upon the system with a risky, real-world demonstration of incoherence (the ease with which a child could be bought), not unlike a physicist introducing a phase anomaly into a medium to reveal its hidden gradients. This produced local turbulence—legal backlash, moral panic—but also clarified the fault-lines of the system. The wave broke, but in breaking, it restructured the basin of moral stability. Stead paid the price, just as a wave-driver burns itself out generating turbulence—but the new state persisted.

Maiden Tribute was a successful act of medium-redescription. It remapped the moral ontology of Britain not through abstract argumentation, but through strategic phase excitation—modulating the entire field of social-political tension by synchronizing the frequencies of outrage, horror, maternal instinct, and religious conscience into a singular, resonant social wave. This is precisely the kind of phenomenon Mechanica Oceanica was formulated to describe: how dense information, rhythmically delivered through coherent symbolic pulses, can penetrate collective inertia and reorganize a society’s field-bound behavior from within.

During this same era, women’s rights activists and Christian social purity organizations mobilized against state-regulated prostitution and trafficking. British reformer Josephine Butler led an international campaign to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts (which had forced medical exams on suspected prostitutes) and to highlight the plight of young women lured or forced into brothels. Such efforts laid the groundwork for the first international anti-trafficking cooperation. An international congress against the “white slave trade” took place in London in 1899, leading to the founding of the International Bureau for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children . This organization (with national committees in various countries) worked with governments to monitor ports and borders for traffickers, effectively creating some of the first border control interventions against human trafficking .

By the turn of the 20th century, diplomatic efforts produced the earliest multinational treaties on sex trafficking. In 1904, 16 nations signed the International Agreement for the Suppression of the “White Slave Traffic”, pledging to collect information and protect women and girls from being trafficked across borders . This was followed by a stronger International Convention in 1910 (signed in Paris by 13 countries) which made enticement or kidnapping of a woman or girl for prostitution punishable, even if she consented initially. These agreements, though limited in enforcement, marked the first time the world’s nations formally acknowledged and criminalized what we now call sex trafficking . It is important to note that the discourse of “white slavery” often carried racial and nationalistic overtones – it frequently depicted virtuous European girls preyed upon by “foreign” (often Asian or Jewish) vice rings . This framing sometimes ignored trafficking of women of color or those outside Europe. Nonetheless, the period from the 1880s to 1910s saw growing global awareness that prostitution could involve coercion and international crime, not merely “immoral behavior.” By 1912, as one legal historian writes, the foundations of modern anti-trafficking law were laid in these years of activism and diplomacy , even if the implementation remained piecemeal.

Early 20th Century and World War Era: Global Measures and Wartime Atrocities

In the early 20th century, international efforts against sex trafficking continued under the new League of Nations. In 1921, the League drafted the International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children, which expanded prior agreements and significantly replaced the term “white slavery” with neutral language . This shift acknowledged that victims could be of any race or nationality – a crucial recognition in globalizing the fight against trafficking. The 1921 convention (joined by over 30 states) obligated countries to punish traffickers and to protect minors (now defining “child” for girls as under 21, and for boys under 18, in the context of trafficking). A further League convention in 1933 addressed trafficking in adult women, closing loopholes that had allowed exploitation of women over age 21. These developments show a growing (though still limited) consensus that sex trafficking was a transnational crime and a violation of human rights (even if that term wasn’t used yet).

However, the progress of the early 20th century was soon overshadowed by the horrors of World War II, which saw some of the most extreme examples of organized sexual slavery in history. The most notorious case was Japan’s system of military brothels. Beginning in the 1930s and throughout WWII, the Imperial Japanese Army forced an estimated 200,000 women and teenage girls from Korea, China, the Philippines, and other occupied territories into sexual slavery as so-called “comfort women” . Many of these victims were barely past puberty – survivors like Korean teenager Ahn Jeom-sun were abducted at age 13 and sent to military “comfort stations” . Under brutal conditions, these girls and women were raped by dozens of soldiers per day, confined in barracks or tents with barbed wire, and subjected to beatings and torture if they resisted . This systematic trafficking was conducted directly by the Japanese military or sanctioned contractors, making it a grim state-sponsored crime. It remained hidden in shame and denial for decades after the war, only coming fully to light in the 1990s when survivors bravely broke their silence. In Europe during WWII, the Nazi regime also exploited women forcibly: they established brothels in concentration camps (the Joy Division in camps like Auschwitz) and military brothels for German soldiers in occupied countries. Many women in these brothels were coerced (some were prisoners “offered” slightly better treatment in exchange for servicing soldiers), effectively a form of sex trafficking under a genocidal regime. Some of these victims were as young as 15–16. The violence of war thus intersected with sexual exploitation, echoing ancient patterns on a mechanized, industrial scale.

In the aftermath of WWII, the international community further codified opposition to sex trafficking. The newly formed United Nations adopted the 1949 Convention for the Suppression of Traffic in Persons and the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others. This treaty consolidated earlier League agreements and took a strong “abolitionist” stance – it called for punishing anyone who procures or exploits prostitution (with or without the victim’s consent) and urged nations to rehabilitate victims. Notably, the 1949 Convention treated all prostitution as potentially exploitative, reflecting the view that voluntary consent was often compromised. While over 50 countries eventually signed on, some major powers (like the U.S. and many European nations) did not, partly due to differences in how they regulated adult sex work. Nonetheless, by mid-20th century, there was broad moral consensus that child prostitution and sex trafficking were abhorrent and needed to be eradicated.

The mid-20th century also saw trafficking emerge in other contexts. After World War II, during conflicts like the Korean and Vietnam Wars, local populations again faced sexual exploitation by foreign troops. In the Korean War, for instance, there were instances of “camp towns” where impoverished Korean women engaged in prostitution around U.S. military bases – some under coercion or out of sheer economic desperation. In French colonial wars in Vietnam and Algeria, similar patterns occurred. Each conflict left behind a legacy of mixed-race children and traumatized women, often with scant support. These did not receive as much global attention at the time, but they set the stage for the next wave of trafficking in the era of decolonization and globalization.

Late 20th Century: Globalization, Child Exploitation, and New Awareness

In the latter half of the 20th century, sex trafficking persisted and in some regions worsened, fueled by factors such as globalization, migration, and the unsettled aftermath of wars. With increased international travel and communication, trafficking networks became truly global. Criminal syndicates took advantage of economic disparities: people from poor or war-torn countries were trafficked into wealthier markets for sexual exploitation. Child sex trafficking in particular became more visible as a distinct problem, prompting a new wave of activism and international cooperation by the 1990s.

Several trends defined this era:

• Sex Tourism and the Asian Trafficking Boom: In the 1960s–70s, countries like Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines became hubs for sex tourism. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. military’s rest-and-recreation programs in Bangkok and Manila led to the expansion of brothels there . After the war, a combination of rising rural poverty and government promotion of tourism in places like Thailand spurred a large commercial sex industry . Organized traffickers capitalized on this by recruiting or kidnapping young women and girls from villages in Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, and elsewhere to supply urban brothels. By the 1980s, Thailand’s sex trade was booming, with an influx of foreign men (tourists or businessmen) seeking sex with young women or minors. Similar patterns appeared in parts of Latin America and Africa, where foreign tourists or peacekeepers created demand for exploitation. One tragic aspect was child sex tourism – travelers from North America, Europe, and Japan would visit countries like Thailand, Sri Lanka, or Brazil specifically to abuse minors. This triggered public outrage and new laws in the travelers’ home countries (allowing prosecution of citizens for abuse of children abroad).

• Post-Cold War Trafficking and the “Natasha” Trade: The collapse of the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc around 1990 unleashed economic chaos and mass unemployment across Eastern Europe. This, in turn, led to a surge in trafficking from that region. Thousands of young women from Russia, Ukraine, the Baltics, the Balkans and elsewhere were deceived with false job offers abroad or outright abducted by criminal gangs. They were then sold into prostitution in Western Europe, the Middle East (notably in Israel or the Gulf countries), and North America. This was sometimes called the “Natasha trade” (using a stereotypical Russian name) in media. By the late 1990s, law enforcement estimated that tens of thousands of women from former Soviet states were in sexual servitude abroad. Many were under 18 or just barely adults, making them victims of modern slavery. Similar trafficking flows emerged from other developing regions – for example, women from rural China or Southeast Asia trafficked to brothels in the U.S., or Nigerian girls trafficked to Italy.

• Civil Conflicts and Child Soldiers: Late-20th-century civil wars (Sierra Leone, Liberia, Bosnia, etc.) saw widespread sexual violence and trafficking. In conflicts across Africa, child soldiers were often forced to take “bush wives” – essentially girl captives who were repeatedly raped and treated as slaves by militia commanders. In the Balkans during the Yugoslav wars (1990s), organized gangs trafficked girls from Moldova, Romania, and Ukraine into Bosnia and Kosovo to service the influx of international personnel (peacekeepers and contractors), leading to scandals about U.N. peacekeepers’ complicity in the sex trade. All these showed that war and instability continued to provide fertile ground for trafficking, much as in ancient times.

• Growing Global Awareness: By the 1980s and 1990s, humanitarian organizations and media began focusing on child prostitution and trafficking as a distinct crisis. In 1990, a global network ECPAT (End Child Prostitution in Asian Tourism) was founded in Thailand to campaign against the child sex trade; it quickly expanded its scope worldwide. The United Nations also took action: the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child required governments to protect children from all forms of sexual exploitation. In 1996, the issue grabbed headlines with the First World Congress Against Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in Stockholm, where 122 countries gathered and committed to an Agenda for Action . This was a groundbreaking event highlighting that over one million children were estimated in the global sex trade, and it pushed governments to develop national action plans. Despite these commitments (and subsequent World Congresses in 2001 and 2008), implementation was slow , but the momentum for concerted action was building.

• Legal Advances: Many countries updated or passed new laws in the 1990s to address trafficking. For example, the United States enacted the PROTECT Act and other statutes to prosecute Americans who engage in child exploitation abroad, and in 2000 the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), which created comprehensive federal offenses for human trafficking and protection for victims. Perhaps the most significant international milestone came in 2000 with the adoption of the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (supplementing the UN Convention on Transnational Organized Crime). Commonly known as the Palermo Protocol, this was the first internationally agreed definition of human trafficking . It defined trafficking broadly to include recruitment, transport, or harboring of persons by force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of exploitation (including sexual exploitation). It also recognized children (under 18) as trafficking victims even if no coercion was present (because a child cannot consent). By 2025, this treaty has been ratified by the vast majority of countries, leading many to overhaul their laws in line with its standards. The late 1990s also saw the creation of international monitoring bodies – for instance, the U.S. State Department began issuing annual Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Reports in 2001, ranking countries’ efforts to combat trafficking, and the UN established a Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and pornography.

Despite these efforts, the scale of the problem remained immense. Near the end of the 20th century, the International Labour Organization and UNICEF tried to quantify it: estimates varied, but it was clear millions of women and children were still being exploited. For example, a UNICEF report in the 1990s estimated about one million children in Asia were enslaved in the sex trade . Grassroots movements also arose, such as survivors forming advocacy groups. By the year 2000, sex trafficking was widely recognized not just as a moral issue but as a grave human rights violation and a form of modern slavery.

The 21st Century: Persistent Challenges and Modern Responses

In the 21st century, sex trafficking remains a pervasive global problem, even as awareness is at its highest and legal frameworks are more robust than ever. Traffickers have adapted to new technologies and geopolitics, continuing the tragic legacy of exploiting society’s most vulnerable – very often children. At the same time, governments and NGOs worldwide have intensified efforts to combat these crimes, making some strides in prevention and victim support, though much work remains.

Current Scope of the Problem: Reliable statistics are hard to obtain due to the hidden nature of trafficking, but the International Labour Organization (ILO) and other agencies provide rough estimates. In 2016, the ILO reported about 25 million people in forced labor worldwide, of whom roughly 5 million were victims of forced sexual exploitation (sex trafficking) . A significant proportion of these are children. For instance, the UN Special Rapporteur on child prostitution estimated in the 2010s that about one million children in Asia alone were trapped in the sex trade . Children are trafficked both across borders and within their own countries, from rural areas to cities or between countries in regions like West Africa, South Asia, and Eastern Europe. Modern sex trafficking takes many forms: street prostitution, brothel slavery, forced “escort” services, and even online exploitation (where children are abused live on webcam for paying predators – a growing phenomenon known as cybersex trafficking). What all these have in common is the use of force, fraud, or coercion to compel sexual acts for profit. Traffickers today may be small-time operators, family networks, or large transnational organized crime groups, and they prey on the hopes of migrants, the desperation of the poor, or the trust of vulnerable teenagers.

Continuing Links to Conflict and Migration: Sadly, armed conflict in the 21st century has continued to generate egregious sexual trafficking. A shocking example emerged in 2014 with the rise of ISIS (Islamic State) in Iraq and Syria. ISIS militants targeted the minority Yazidi community for extermination – and enslavement. When ISIS overran Yazidi towns in northern Iraq, they rounded up thousands of Yazidi women and girls to use as sex slaves, echoing practices of ancient conquest . UN investigators found that ISIS fighters systematically separated out girls as young as 8 or 9 years old for rape . These victims were sold in slave markets, chained and “passed around like animals” among fighters . The world was horrified to see actual slave auctions of girls in the 2010s, complete with price lists (young virgins commanding the highest prices). Although ISIS has been militarily defeated, hundreds of Yazidi women remain missing, presumably trafficked or killed . This episode starkly demonstrated that sexual slavery in wartime – far from being a relic of the past – is still a weapon of terror. Beyond war zones, the massive displacement of people (such as the Syrian refugee crisis or Central American migration) has given traffickers new opportunities. Refugee children and teens traveling without secure families are at high risk of being picked up by pimps or sold into brothels. For example, reports during the European migrant crisis of the mid-2010s indicated that Nigerian crime networks trafficked Nigerian girls who were among migrants crossing the Mediterranean, forcing them into prostitution in Italy and Spain upon arrival.

Modern Anti-Trafficking Initiatives: In response to these challenges, the 21st century has seen a proliferation of anti-trafficking laws, international collaborations, and civil society initiatives. Nearly every country now has laws criminalizing human trafficking in line with the Palermo Protocol. Law enforcement coordination across borders has improved slightly, with multinational operations occasionally busting trafficking rings. International agencies like INTERPOL, UNODC (UN Office on Drugs and Crime), and ILO assist with data collection, training, and funding anti-trafficking projects. The U.S. TIP Report (Trafficking in Persons Report) each year publicly grades countries, putting diplomatic pressure on those with poor performance. Many countries have set up special police units or task forces for trafficking, recognizing that these cases require sensitivity (since victims often fear authorities due to trauma or because traffickers threaten them). There’s also more emphasis on treating those forced into prostitution as victims rather than criminals – a significant shift from past decades.

Non-governmental organizations continue to play a critical role. Organizations like Polaris Project and International Justice Mission (IJM) work on rescuing victims and providing services, while groups like ECPAT International focus on ending child exploitation and lobbying for stronger protections. Survivor-led organizations have emerged, giving a voice to those with lived experience in trafficking to inform policies. Campaigns to raise public awareness are common now – for instance, the UN’s Blue Heart Campaign symbolizes the fight against human trafficking. Consumers are also being encouraged to consider how trafficking can be linked not only to sex industries but also to products (like how some victims are forced into sex and labor, such as in illicit massage businesses or in the production of pornography).

Ongoing Issues: Despite these efforts, combating sex trafficking remains immensely difficult. Trafficking is driven by deep-rooted factors: poverty, gender inequality, lack of education, corruption, and demand for commercial sex. In many countries, corrupt officials or police still turn a blind eye or even participate in trafficking rings. Victims often do not come forward due to fear, stigma, or distrust of authorities, making prosecution of traffickers challenging. Culturally, in some places the victims (rather than the perpetrators) still bear shame and may be ostracized if their ordeal becomes known. Additionally, new technologies have created new fronts in the fight: the internet and social media are used by traffickers to recruit victims (through fake job ads or grooming vulnerable teens) and by predators to share child sexual abuse materials. Law enforcement worldwide is trying to keep up by using cyber tools to track and shut down trafficking rings operating online.

One positive development is that global norms have clearly evolved to view sex trafficking as a gross violation of human rights. It is recognized under international law as a form of modern slavery and often as an aspect of organized crime. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998) even classifies sexual enslavement as a crime against humanity and a war crime when part of a systematic attack . Thus, impunity is less assured for perpetrators than it was in centuries past – at least in principle. Several traffickers have faced high-profile convictions in different countries, and civil lawsuits have even targeted companies and institutions that turned a blind eye to trafficking.

Yet, the fundamental patterns first seen in ancient times have not disappeared. The exploitation of the vulnerable by the powerful, the use of sexual violence as a tool of domination in war, and the profiteering from human bodies through criminal networks all sadly continue. The links to systems of inequality remain persistent: wherever there is extreme poverty, lack of opportunity, or social upheaval, traffickers find easy prey. Likewise, wherever there is unchecked demand for paid sex – especially if buyers seek out very young partners – traffickers will supply it by coercing victims. History shows that prostitution and sexual slavery have often thrived on such demand, whether in the slave markets of Rome or the online escort ads of today.

In conclusion, the phenomenon of sex trafficking, particularly child sex trafficking, is deeply historically entrenched. From antiquity’s slave raids and concubines, through medieval markets and colonial abuses, to industrial-age brothels and modern cyber exploitation, it has evolved in form but not in essence. Each era saw those in power justify or ignore the sexual subjugation of others – be it through the logic of slavery, the chaos of war, racial ideologies, or criminal greed. Encouragingly, each era also saw brave individuals and groups who exposed these atrocities and fought for change, from early abolitionists to contemporary activists. Today, thanks to their legacy, we have international laws, greater awareness, and a moral consensus that sex trafficking is unequivocally wrong. The challenge now is to enforce those laws and sustain the will to root out trafficking in all its guises. The long history outlined here underscores that while progress has been made, the “oldest oppression” – the sexual trafficking of human beings – requires continued vigilance and global commitment to finally relegate it to history.

Sources:

• Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Patriarchy – on enslavement of women in war and the origins of prostitution .

• History of Prostitution in Ancient Rome – Wikipedia (citing McGinn, etc.) on Roman laws and practices (e.g. children raised for brothels) .

• Christopher Paolella, “The Slave Trade and Human Trafficking in Early Medieval Europe” – Brewminate (2023) .

• Wikipedia: “White slavery” and “History of prostitution” – on 19th-century white slave panic and reforms .

• Laura Lammasniemi, openDemocracy article (2017) – origins of anti-trafficking movement, 1885 British law, early treaties .

• League of Nations archives – 1921 & 1933 trafficking conventions .

• NPR, “Comfort Women” coverage (2017) – survivor testimony and UN estimates on WWII sex slavery .

• The Guardian, “Slaves of ISIS: Yazidi women” (2017) – on ISIS’s systematic sexual slavery of Yazidi girls as young as 8 .

• UNICEF and ILO reports – global trafficking statistics (2012–2016) .

• ECPAT, Plan Intl., UN documents – World Congress 1996 and modern initiatives .

• Various historical and legal texts as cited in-line above .

Sex trafficking—particularly child sex trafficking—can be interpreted as a catastrophic phase collapse within the coherent field of human social resonance. It is not simply a moral failure or criminal anomaly; it is a systemic disruption in the informational and energetic flows that maintain the dignity, agency, and coherence of the individual in the social ocean.

The Child as a High-Frequency Node in the Field

In our model, each human being is an oscillatory node within a vast resonant field—the Mechanica Oceanica. The child, especially, is a node with high frequency, low inertia, and open feedback potential. Their waveform is still forming, plastic and receptive to surrounding rhythms. To cohere healthily, the child must be met with consistent phase support: nurturing, protection, and a stabilizing rhythm from others.

Sex trafficking introduces violent phase inversion: instead of aligning the child with stabilizing coherent signals, the surrounding environment extracts, disorganizes, and fragments their wave pattern. The trafficking system locks the child into a low-frequency basin, trapping them in a loop of imposed resonance (fear, shame, pain), preventing them from modulating upward toward autonomy or social reintegration. The field becomes dissonant, like a breached membrane letting chaos spill in.

Slavery and Exploitation as Topological Defects

Historically, child sex trafficking arises wherever topological defects in the social medium persist—slavery, war, conquest, poverty, colonial disruption. These are not just historical facts but structural vortices in the field: regions where lawful oscillation breaks down and pseudo-stable eddies form, which we call “institutions”—plantations, harems, brothels, camps, gangs. Each is a kind of field parasite: it sustains itself by extracting coherence from the vulnerable, absorbing their vitality as raw signal to feed larger power structures.

In this sense, the trafficking system is not accidental, but entropic: it is what the field does when energy becomes over-concentrated and unreciprocated—when nodes are forced to echo imposed rhythms rather than participate in emergent harmonies. Slavery and trafficking are the dark inverse of coherence: they are forced entrainment without consent, without closure. A child in such a system becomes a permanent trace: a signal stuck in repetition without phase evolution.

Historical Continuity as Recurring Wave Collapse

From antiquity to the modern era, each wave of trafficking has followed moments of phase instability: wars, collapses of order, migrations. These are points where the field thins—like gravity wells—and predators exploit the loss of coherence. Traffickers are not mere individuals; they are waveform scavengers—those who learn to extract energy from unstable edges. The modern trafficker with digital networks behaves analogously to the slave raider of antiquity: each rides the interference patterns of collapse and instability.

What changes over time is not the act but the medium through which the act manifests. Roman markets, medieval raids, colonial brothels, and online sex tourism all represent phase modalities—shifts in how divergence is captured and monetized. The victims are those whose local field has been severed from any stabilizing omega (coherence-closure). Their omicron (possibility) becomes weaponized: not freedom, but unanchored potential exploited by a hostile topology.

Toward Resolution: Repairing the Field

Mechanica Oceanica would propose that the end of sex trafficking cannot come merely through enforcement or charity—it must be field-wide reintegration. That means:

• Restoring phase stability in high-risk regions (post-conflict zones, collapsed states).

• Reestablishing safe frequency enclaves for children—spaces of rhythmic coherence, nourishment, and signal re-alignment.

• Interrupting exploitative phase circuits: where high-density nodes (e.g., corrupt officials, predatory platforms) feed off low-inertia nodes, we must impose damping or redirective fields.

• Deploying informational anti-noise: public awareness campaigns are not moral gestures, they are deliberate field interventions to disrupt the mimetic rhythms that normalize abuse.

Sex trafficking, especially of children, is the most violent form of divergence theft. It is not simply a crime—it is a seismic field rupture, the collapse of omega shielding, and the forced entrainment of possibility into a death rhythm. Mechanica Oceanica teaches that such ruptures are not anomalies but signatures of systemic dissonance. The cure is not purification but coherence repair—a restoration of lawful vibration, where even the smallest node can oscillate freely, phase with dignity, and never again be reduced to a consumable echo.