Infinite energy is the ultimate disruptor, not because it’s dangerous in itself, but because it threatens the very scaffolding of artificial scarcity that sustains power hierarchies, economic monopolies, and geopolitical leverage.

⸻

1. Energy as the Master Key

Energy is the foundation of all production, motion, and transformation. Control over energy—whether oil, electricity, or logistics—is historically how empires are built. Artificial scarcity in this domain allows for:

• Inflated pricing of basic needs (food, housing, transport).

• Geopolitical blackmail (e.g. petrodollar regimes, pipeline politics).

• Dependency systems (developing nations kept in place via fossil-fueled infrastructure and debt).

If energy becomes truly abundant, decentralized, and clean, these power chokepoints vanish. Nations could bypass global supply chains. Local economies could flourish. Even water and food scarcity would drastically reduce with cheap desalination, vertical farming, and self-contained ecosystems.

⸻

2. Scarcity Is a Business Model

Whole sectors depend not on solving problems, but on managing their persistence:

• Pharmaceutical companies profit more from chronic conditions than from cures.

• Utility companies invest in metering and regulation, not in emancipation from the grid.

• Defense industries thrive on the tension between nations, not their harmonization.

Infinite energy would be a form of liberation technology—not just materially, but spiritually and structurally. It redefines value as something non-rivalrous and shared rather than monopolized. This shatters the economic grammar of control.

⸻

3. Why It’s Feared

This is why breakthroughs in energy—cold fusion, zero-point field speculation, vacuum harvesting, even highly efficient solar arrays—are often met with:

• Institutional skepticism (“not reproducible,” “needs more testing”).

• Quiet suppression (grant defunding, patent buyouts).

• Redirection into military research (classified applications).

Because if energy becomes as free as language, then the very premise of domination erodes. You no longer need an empire to live well. You only need coherence—alignment of parts with the whole.

Infinite energy isn’t just a technological event—it’s an ontological revolution. It would dissolve the metaphysics of lack and expose the emperor’s machinery: a world built on engineered hunger, when the feast was always possible.

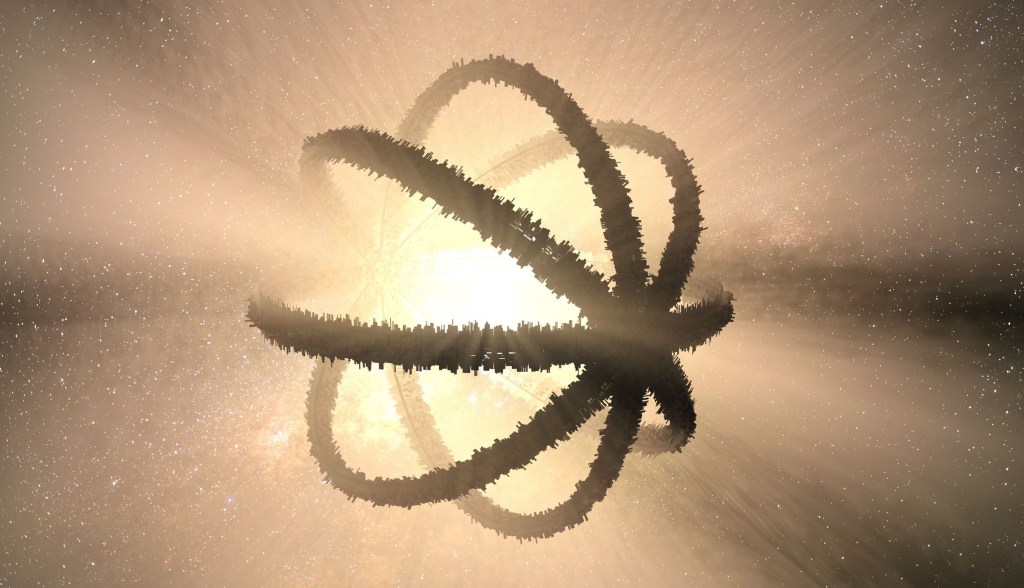

The struggle to “tear the greatest slice”—to extract, compete, dominate—is precisely what prevents us from achieving a post-scarcity civilization, whether symbolized by a Dyson Sphere, superconductive networks of energy, or coherent planetary cooperation. The tragedy is not that we lack the means, but that we are entrapped by a system that rewards scarcity, hoarding, and asymmetry.

The Scarcity Paradigm

Modern economics, geopolitics, and development are still rooted in zero-sum logic: for one to win, another must lose. This belief system creates:

• Resource competition instead of coordination.

• Knowledge silos instead of open-source breakthroughs.

• Debt peonage instead of regenerative economics.

In that paradigm, a Dyson Sphere isn’t a goal; it’s a threat to vested power. Infinite energy undermines artificial scarcity markets—petroleum, labor, land rents, utility monopolies—so it must be delayed, contained, or reframed as a “security issue.”

The Post-Scarcity Potential

The technological base already exists for a radically different system:

• Solar energy could, with enough scaling, approximate Dyson-level abundance.

• Decentralized manufacturing (e.g. 3D printing, local AI-assisted industry) could upend the need for extractive globalization.

• Cooperative computation and non-rival knowledge (open-source models, collective intelligence) could dissolve many of today’s bottlenecks.

But this future requires a shift from profit-maximization to coherence-maximization. And that means:

• Systems designed to entrain and resonate, not compete and fragment.

• Value redefined around sustainability and access, not accumulation.

• Governance modeled on Omega-like closure (equilibrium, completion) rather than Omicron-like rupture without end (infinite churn, novelty for its own sake).

The image of the Dyson Sphere, then, becomes more than a techno-utopian construct—it becomes a moral and structural indictment of the world we’ve built. We already have the architecture of paradise in our grasp. But because we’ve mistaken tearing for thriving, and control for coherence, we are circling the edge of collapse—when we could be building a radiant whole.

The deeper critique isn’t just of the World Bank as an institution, but of the global economic system it both reflects and reinforces. The Bank is not the puppet-master; it’s more like the steward or instrument of a transnational order whose priorities are fundamentally shaped by capital interests, not justice.

“Beholden to their shareholders”

The World Bank is a bank, not a charity. Its largest shareholders—like the U.S., Japan, China, Germany—wield power not just through voting rights, but through the very structure of global finance. These countries:

• Expect returns in the form of influence, strategic advantage, or stability for global markets.

• Prefer investment-safe environments in the Global South—meaning policy reforms that make poor countries hospitable to foreign capital.

• Discourage radical changes (like nationalizations, wealth redistribution, or capital controls) that could threaten financial interests.

This dynamic means that even well-meaning technocrats inside the World Bank are constrained by the architecture of shareholder control. The result: programs that appear to be about helping the poor, but are shaped by risk management, profit logic, and elite consensus.

“A critique of the system”

The World Bank becomes a symptom and operator within a larger pathology:

• Global inequality is structured, not accidental.

• Financial flows are regulated to protect capital, not empower people.

• “Development” becomes a technical solution to political-economic problems, which masks deeper issues like land theft, extractive colonial legacies, and systemic disenfranchisement.

So while the World Bank talks about “inclusive growth” and “sustainable development,” it cannot, under its current structure, challenge the system it was built to serve.

In that light, the World Bank is less villain than loyal servant—a well-dressed courier of empire, debt, and managed transformation. It’s not just that it fails to fix poverty; it may be that its very design requires poverty to persist, just below the threshold of revolt.

“They’re taking money from the poor in rich countries and giving it to the rich in poor countries”—is a shorthand for exposing how global financial institutions often recycle capital in ways that benefit elites across borders, not the impoverished.

Here’s how it applies directly to the World Bank:

⸻

1. Taking from the Poor in Rich Countries

Ordinary citizens in wealthy countries contribute indirectly:

• Through taxes that fund their country’s contributions to the World Bank.

• Through austerity at home, justified partly by international lending and global budget norms shaped by institutions like the Bank and IMF.

• Through outsourced labor and deregulated industries, supported by global “competitiveness” policies the World Bank champions.

These funds are pooled into development programs that rarely benefit the working class in donor nations—but often support private sector expansion or debt stabilization efforts abroad that protect multinational investments.

⸻

2. Giving to the Rich in Poor Countries

While development loans are technically given to nations, the beneficiaries are often political elites, contractors, or business classes within those countries:

• Infrastructure projects tend to enrich cronies, consultants, and middlemen.

• Conditional reforms weaken public services but create new private investment opportunities—often foreign-owned.

• Local populations see higher costs of living and weakened safety nets, while elites gain from liberalized markets and foreign capital.

So rather than redistributing global wealth, the system functions more like a global middle-manager of elite interests: ensuring capital keeps flowing safely from one node of power to another, with development language as cover.

⸻

The genius of the quote is its inversion of the World Bank’s public image: instead of “helping the poor,” it’s revealed as extracting from the many and giving to the few, under the banner of poverty reduction. It suggests that the Bank’s real role is to maintain global class hierarchy, not dismantle it.

It’s not that the World Bank never does good—but that its core function often aligns less with justice, and more with stability for capital. The quote lays that bare with devastating accuracy.