Fermilab, a sprawling research center on the prairie west of Chicago, is best known for firing the world’s most intense pulses of protons down a chain of accelerators, then using the debris to create beams of neutrinos—near-invisible particles that zip straight through Earth. Because the lab controls exactly when each proton pulse is launched, it can timestamp the resulting neutrinos to within a few billionths of a second and send them hundreds of kilometers to gigantic underground detectors. For our “electromagnetic-ocean” model, that precise stop-watch capability is gold: by shooting a tightly timed burst of neutrinos toward a distant detector while simultaneously flashing a synchronized laser signal through fiber-optic lines, scientists could compare the two arrival times and look for the microsecond-scale delay our model predicts if neutrinos surf the ocean differently from light. In plain terms, Fermilab gives us a ruler and a stopwatch large enough to spot a tiny mismatch in how two kinds of ripples move—exactly the kind of real-world test that can confirm or refute our theory without waiting for a rare cosmic event like a supernova.

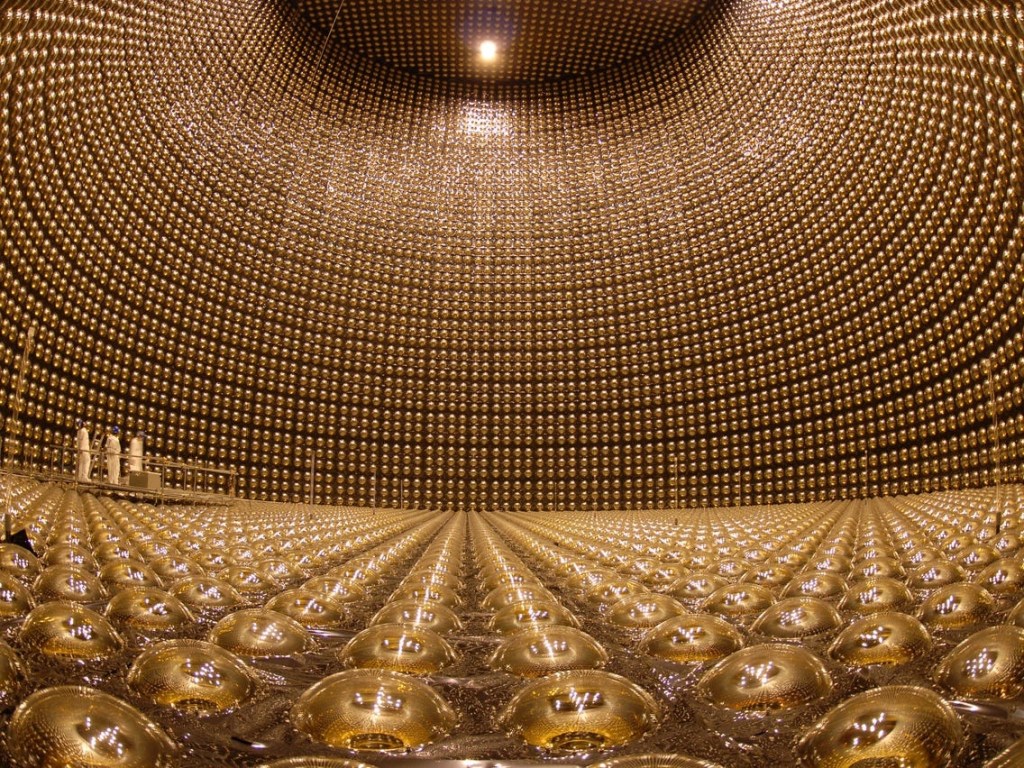

Deep beneath a mountain in southern China, JUNO is being built as a giant transparent sphere—thirty-five meters across—filled with 20 000 tons of liquid that flashes whenever a neutrino bumps into an atomic nucleus. Ringed by nearly 50 000 light sensors, this “cosmic fish-bowl” will time-stamp each tiny flash to a few ten-millionths of a second and measure the energy with high precision. When the next nearby star explodes as a supernova, JUNO will record thousands of neutrinos one by one, while telescopes catch the first burst of light from the same event. By comparing those two stop-watches, researchers can check whether neutrinos and photons really traverse space at exactly the same pace or whether, as our electromagnetic-ocean model predicts, light suffers an extra microsecond of drag along the way. In everyday terms, JUNO is like a giant underground camera waiting to film the universe’s next fireworks display—and its ultra-fast timing could reveal whether space itself slows light just a hair more than it slows neutrinos.

At the South Pole, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory turns a cubic kilometre of crystal-clear Antarctic ice into a gigantic three-dimensional net of light sensors, waiting for the faint blue glow that appears when a high-energy neutrino streaks through and outruns light in the ice. Each sensor records the flash with nanosecond precision, so when a distant cosmic explosion—like a gamma-ray burst or a magnetar flare—fires both neutrinos and a burst of gamma-ray light toward Earth, IceCube can time the neutrinos almost to the heartbeat, while orbiting satellites time the photons. By lining up those two cosmic stop-watches, scientists can check whether the photons arrive a microsecond later than expected, the hallmark of the tiny “drag” our electromagnetic-ocean model predicts for light but not for neutrinos as they cross interstellar space. In other words, IceCube is a colossal frozen telescope whose split-second timing lets us test whether space itself tugs slightly harder on light waves than on neutrino waves.

Perched on the hills above Stanford, SLAC fires electrons down a straight three-kilometre tunnel—the longest linear accelerator in the world—and then bends those electrons through powerful magnets to create ultrabright X-ray laser flashes that can photograph atoms in motion. Because SLAC’s electronics stamp each laser pulse and each electron bunch to trillionths of a second, researchers can send carefully shaped “twisted-light” pulses through custom crystals and watch how their speed changes with the light’s internal swirl. That laboratory trick is a miniature version of our electromagnetic-ocean test: if different twists of light drift apart by the tiny amount our model predicts, it would reveal the same coherence-vs-drag effect we expect for photons in space. In plain terms, SLAC acts like a high-tech racetrack and stopwatch for exotic light pulses, letting us probe—on a tabletop—the subtle tug that the electromagnetic ocean might exert on waves as they propagate.

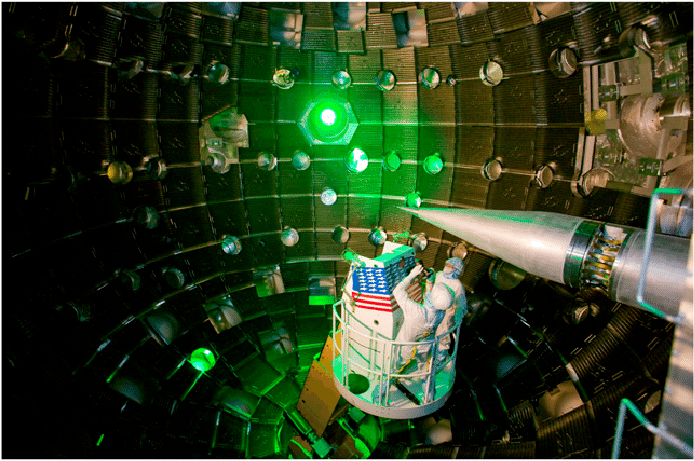

The National Ignition Facility in California is the world’s most energetic laser: 192 giant beams converge on a pinhead-sized fuel pellet, squeezing it to temperatures and densities found in stars so researchers can study fusion up close. Each shot also creates an ultra-hot, ultra-dense plasma—a seething, incandescent “ocean” of charged particles and light. By tracking how short laser probes or X-ray flashes slow and spread as they pass through this plasma, scientists can look for the tiny, topology-dependent drag that our electromagnetic-ocean model predicts should appear whenever waves traverse an intensely turbulent medium. Think of NIF as a brief, man-made star in a bottle: its fleeting micro-explosions give us a controllable way to see whether extreme plasmas tug on light in just the subtle way our theory anticipates.

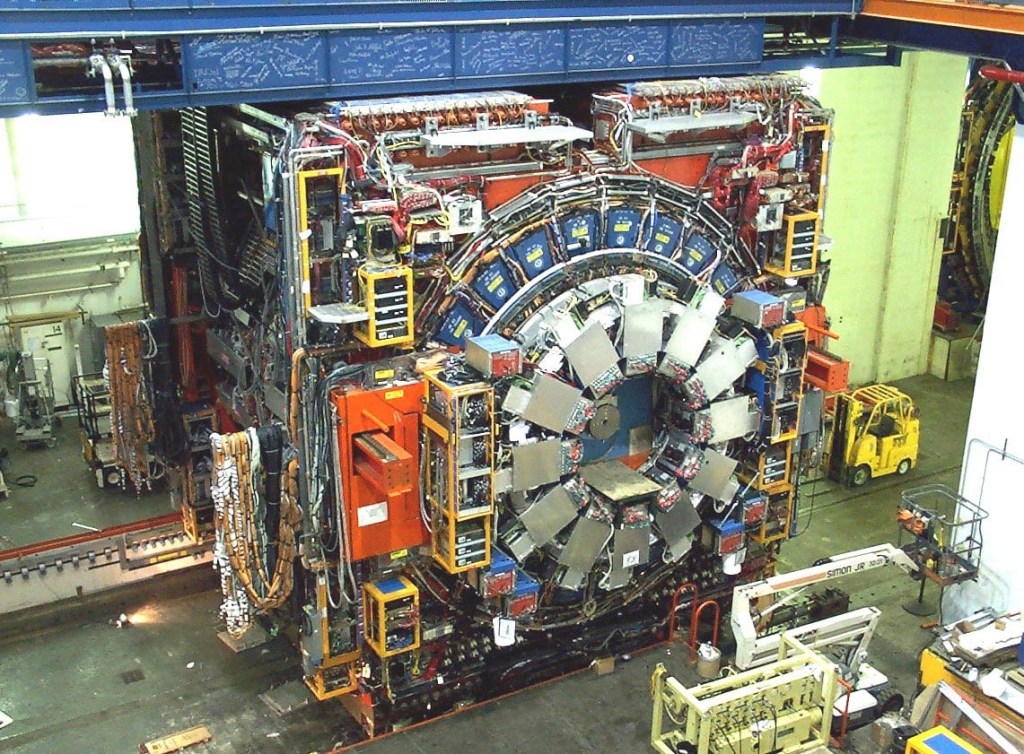

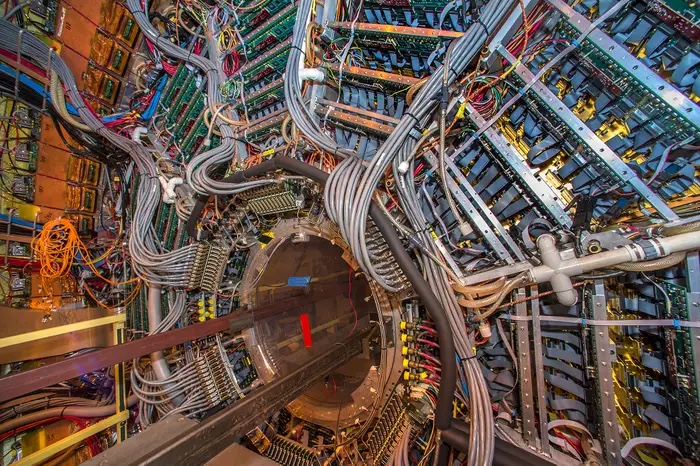

Brookhaven’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) smashes gold nuclei together at almost light-speed, recreating—for a fleeting instant—a tiny drop of the quark–gluon plasma that filled the universe microseconds after the Big Bang. Detectors such as STAR and PHENIX capture the spray of particles and photons that erupt as this super-hot fluid cools, time-stamping each track to billionths of a second. Although RHIC’s plasma is governed by the strong force rather than electromagnetism, it provides a vivid analogue of our “electromagnetic ocean”: a dense, wave-supporting medium in which disturbances propagate, lose energy, and shed radiation. By watching how electromagnetic signals (direct photons or electron–positron pairs) emerge from, and are subtly delayed by, the quark–gluon plasma, researchers can test whether the same coherence-versus-drag interplay predicted by our model appears in an extreme, strongly interacting environment. In simple terms, RHIC offers a tiny, tunable fireball whose flashes of light let us probe how any wave—whether carried by quarks or by photons—might be nudged, slowed or reshaped by the medium it travels through.

Japan’s Proton Accelerator Research Complex—J-PARC—sits on the Pacific coast at Tokai and hurls one-megawatt pulses of protons into targets every few seconds. Those impacts create intense beams of neutrinos that shoot 300 km through Earth to the Super-Kamiokande detector near Kyoto, their departure times known to within a few billionths of a second. Because the facility’s clocks also tag accompanying flashes of light sent down fiber links with the same precision, J-PARC gives experimenters a laboratory “race track”: they can fire neutrinos and photons on parallel courses and see whether the neutrinos reach the finish line a microsecond sooner, exactly the tiny head-start our electromagnetic-ocean model predicts if light experiences a bit more drag. In everyday terms, J-PARC is a giant timing gun and stop-watch rolled into one, whose ultra-regular pulses let us test whether space treats neutrino ripples and light ripples truly identically or just almost so.

DESY, on Hamburg’s old Elbe marshland, runs powerful electron accelerators that whip subatomic particles to near-light speed and then wiggle them through magnetic “undulators” to produce Europe’s brightest X-ray laser flashes; these X-rays act like stop-action cameras that can freeze chemical bonds mid-dance or map the internal weave of new materials atom by atom. Because DESY’s timing electronics tag each electron bunch and the resulting light pulse to trillionths of a second, researchers can send specially structured beams—such as “twisted” light carrying extra angular momentum—through custom photonic crystals and watch for the minute, shape-dependent slow-downs our electromagnetic-ocean model predicts. In essence, DESY is a high-precision light forge: it lets us craft exotic wave packets, fire them into designer “oceans” made of glass or nano-metamaterials, and measure whether different twists or colors shed energy and lag behind by the few billionths of a second that would signal the subtle drag our theory anticipates.

LIGO consists of two L-shaped observatories in the United States, each with vacuum-sealed arms four kilometres long, where lasers bounce between mirrors so steadily that even a stretch or squeeze of space one-ten-thousandth the width of a proton shows up as a flicker in the light. Although LIGO’s quarry is gravitational waves, not neutrinos or photons racing across cosmic distances, its value to our electromagnetic-ocean program lies in timing discipline: the facility’s lasers, mirrors, and GPS-disciplined clocks have been tuned to keep track of picosecond shifts while filtering out seismic rumbles, thermal drifts, and electronic chatter. By borrowing LIGO’s clock-synchronisation techniques—white-rabbit fibre links, redundant atomic clocks, and real-time calibration pulses—we can tighten the stop-watches at JUNO, J-PARC, or Fermilab, shrinking their systematic errors below the microsecond window where our model’s tiny light-versus-neutrino delay should appear. In short, LIGO is a masterclass in taking nature’s faintest signals and nailing down their timing; its expertise lets other experiments measure the electromagnetic-ocean effect with the precision that theory demands.

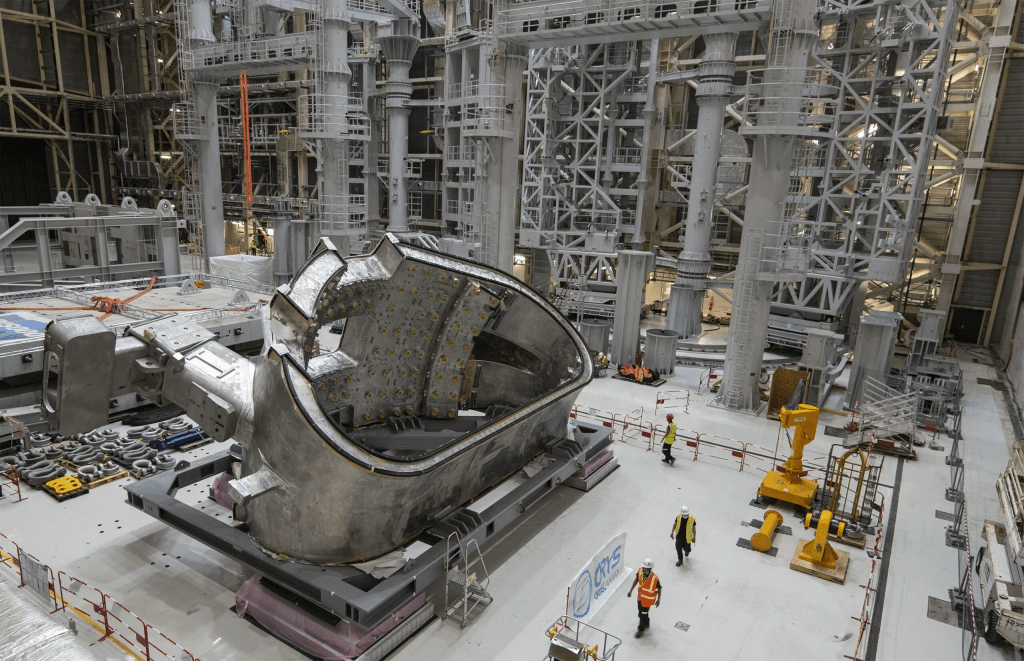

ITER, the giant doughnut-shaped fusion machine rising in southern France, will confine a 150-million-degree plasma with the strongest superconducting magnets ever built, trying to make atoms fuse and release more energy than the reactors’ 18-story cryostat consumes. For our electromagnetic-ocean picture it is a superb “wave tank”: inside the torus, microwaves, lasers, and radio waves already planned for heating and diagnostics must cross a seething sea of charged particles whose density and turbulence can be dialed up or down shot-by-shot. By timing how these probe beams slow, spread, or shed faint side-bands as the plasma parameters change, researchers could look for the slight, topology-dependent drag our model predicts whenever electromagnetic waves traverse a highly twisted medium. In plain terms, ITER will create a man-made star whose glowing plasma lets us watch light itself struggle through a stormy ocean and check whether that struggle matches—or subtly departs from—what standard physics expects.