A pluralism that doesn’t collapse into provincialism must preserve openness to alterity without reducing difference to familiarity. It acknowledges the reality of many worlds, lifeways, and truths without fragmenting into isolated, self-contained enclaves. To achieve this, pluralism must be more than a catalogue of tolerated viewpoints; it must be structured by a commitment to relational universality—a mode of engagement where the universal is not a top-down abstraction but something negotiated between particularities. Such a pluralism listens without preempting, responds without annexing, and maintains fidelity to the tension between coherence and divergence. This means cultivating forms of thought and institutions that remain porous rather than defensive, committed to resonance rather than domination. It’s the difference between a world mosaic and a walled garden: the former is alive with border-crossings, translation, and frictional coherence; the latter merely multiplies sameness under different banners. A non-provincial pluralism refuses both monoculture and relativistic withdrawal—it risks encounter. In this sense, it bears a structural kinship to diaspora, pilgrimage, or dialogue: it requires movement, vulnerability, and the capacity to be changed in relation.

Such a pluralism cannot be grounded in mere tolerance, which often masks a hidden hierarchy—tolerating as one endures what one has already deemed marginal. Nor can it be built on an aesthetic appreciation of difference that leaves power relations untouched. Instead, it must be enacted through structures of mutual intelligibility that do not erase opacity. This demands a language—and perhaps more crucially, a listening—that can hold silence as part of speech, allow the sacred to remain unexhausted by translation, and admit that not all difference can or should be mediated into consensus. It is a political, epistemological, and spiritual discipline. The risk of provincialism arises when particular identities or cosmologies become closed loops, ceasing to draw breath from the larger world. But the answer is not to abandon rootedness. Rather, it is to recognize rootedness as a portal, not a prison. The rooted tree reaches outward through its branches even as it delves deeper underground. So too, a non-provincial pluralism draws nourishment from tradition while extending toward others—not to assimilate them, but to co-resonate with them. Its orientation is not centripetal or centrifugal, but spiralic: moving in relation, never collapsing the many into the One, nor dispersing the One beyond recovery in the many.

In The Book of Questions, Jabès recounts a saying from the rabbinic tradition:

“People think the bird is free, but it is the flower that is free. Because it is rooted.”

This paradoxical aphorism reverses our intuitive associations—birds as symbols of freedom, flowers as bound—by reframing freedom not as unbounded movement, but as grounded being. The bird, always in flight, is never at rest, never at home. Its freedom is flighty, ephemeral, a constant escape. The flower, by contrast, does not flee. It remains, blooms, opens itself to light, to weather, to the gaze of others. It is free not because it can leave, but because it can stay—because it is sustained by depth, connection, and belonging. For Jabès, and for the rabbinic imagination he channels, this saying resonates with exile, language, and the Jewish condition of being both rooted in text and dispersed across worlds. It speaks to a deeper freedom that does not lie in detachment, but in faithful anchoring—in the capacity to grow, to speak, to be vulnerable, precisely from a position of rootedness. In this way, the flower’s “freedom” becomes an image of spiritual responsibility: to be grounded is not to be static, but to be open to revelation.

This teaching subverts the modern ideal of freedom as autonomy, as escape from all bounds. The bird may appear free because it slips from our grasp, defies enclosure, writes temporary calligraphy across the sky. But it is always fleeing—never arriving. The flower, in contrast, commits itself to place. It does not resist the soil, the sun, the rain; it receives them. Its rootedness is not a limitation but a condition of flourishing. The flower becomes free within its form, by surrendering to its context rather than evading it. Freedom here is not about overcoming necessity, but entering into right relation with it. In Jabès’ poetic and theological universe, this insight also mirrors the condition of language and exile. The word, like the flower, must be rooted—in silence, in memory, in loss. It cannot merely flutter through semantic airspace; it must grow from the dark loam of tradition and rupture. In a world fractured by dispersion and suffering, the deepest freedom is not escape but witness: remaining, remembering, returning. So too the pluralism you invoked earlier: a flower-pluralism, grounded, particular, yet open—free not because it flies over the world, but because it blooms within it.

In On Escape (De l’évasion, 1935), Emmanuel Levinas explores the experience of being itself as a kind of suffocation—a stifling, inescapable enclosure. He describes the human condition not as being-at-home in the world, but as being trapped in the fact of existence. This is not about social or political imprisonment, but something more primordial: an ontological nausea, a horror of being itself, what he calls la nausée de l’être. The self wants to escape not from this or that situation, but from the unbearable there is (“il y a”)—the brute fact that there is being, and that one is stuck within it. Levinas’s term escape (évasion) does not mean physical flight or distraction. It names a metaphysical yearning to exit being, to be released from the anonymous, grinding presence of existence that offers no exterior. In this way, he anticipates and diverges from Heidegger. Whereas Heidegger frames being as the horizon for understanding and care, Levinas sees it as oppressive when viewed from the position of a subject that does not choose to be. He writes: “To be cast into being is already to be imprisoned in it.”

What makes On Escape remarkable is that it doesn’t yet offer a solution in terms of the ethical relation—his later signature move—but instead dwells in the desperation of the impasse. The desire to escape is, for Levinas, a deeply human longing to go beyond being—to a “otherwise than being,” a transcendence not of idealism but of radical difference. This is not suicidal negation, but a protest against the neutrality and indifference of being, a first movement of subjectivity toward alterity, toward something wholly other. This early work sets the stage for his later ethics: where escape will no longer mean fleeing into nothingness, but being called beyond oneself by the face of the Other. But here, the cry has not yet met its answer. It is the raw, trembling awareness that freedom may begin not with mastery over being, but with the recognition that to be is already a kind of captivity.

Levinas characterizes this condition as one of immanence without escape—not because the world is full, but because it is too empty, too indifferent. He writes of “the weariness of being,” a fatigue not caused by work or effort, but by the sheer weight of existing. This weariness reveals the absurd repetition of being: it has no outside, no narrative, no finality—only a cycling, a pressure that cannot be evaded. In such a situation, the self does not merely want rest; it wants release from itself. The desire for escape becomes the mark of transcendence—proof that the subject is not fully contained within the world’s categories, that there is something in the human that does not consent to ontology. This anticipates Levinas’s later inversion of Western philosophy: instead of starting with being as what must be understood and disclosed, he begins with the impulse to get out of being, to refuse its terms. What On Escape makes clear is that this refusal is not nihilism, but the first ethical gesture: the yearning for something beyond sameness, a cry for alterity before alterity is even encountered. The subject’s revolt against being is already a sign that another dimension is possible, one not reducible to presence, representation, or comprehension. Escape, then, is not a lapse in courage—it is the very birth of responsibility.

Vigilance

“Where are you hiding, Dolores Haze?

Why are you hiding, darling?

(I talk in a daze, I walk in a maze

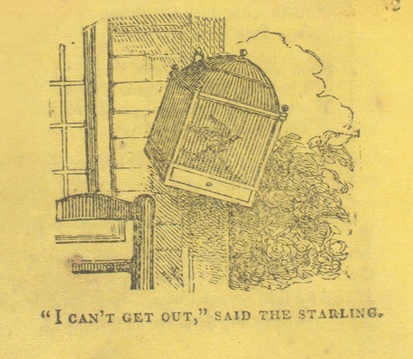

I cannot get out, said the starling).”

The vigilance Levinas later describes, especially in God and Philosophy and Otherwise Than Being, emerges as the maturation of that original cry for escape in De l’évasion. There, the self was desperate to flee the suffocating immanence of being. But later, Levinas reconceives this impulse not as a failed metaphysical gesture, but as the ethical awakening itself—a vigilance that keeps watch for the Other, even before the Other arrives. This vigilance is not theoretical; it is not the neutral eye of philosophy. It is insomnia, exposure, being-on-edge—not because of anxiety, but because one has been called. In God and Philosophy, Levinas writes that the idea of God is not an idea among others—not even the highest or most infinite idea—but an “excess over the thought that thinks it.” God, for Levinas, is not a being within being, nor the culmination of ontology, but that which disturbs ontology from beyond. The name “God” refers to the trace of this beyond, a kind of infinite responsibility that cannot be gathered into the Same. This is why Levinas links the ethical relation with vigilance: to be vigilant is to resist the laziness of totality, to refuse to let the face of the Other be subsumed into concept or category.

This vigilance is a form of ethical wakefulness, a refusal to return to sleep in the comfort of comprehension. In this sense, what began in On Escape as a metaphysical scream—“let me out!”—becomes in his later work an attentiveness to what exceeds being, to the Face, to God as the “infinite in the finite.” And yet the movement is continuous: both are responses to the horror of enclosure, the terror of a world without rupture. Both name a subjectivity that cannot bear to be whole on its own. The escape becomes a standing vigil. The scream becomes listening. In this light, vigilance is not the activity of a sovereign subject, but the very undoing of sovereignty. The vigilant self is interrupted—not master of its time or thoughts, but held hostage by the Other, open to the unforeseeable. This vigilance bears the trace of divine transcendence not because it sees God, but because it remains awake to what cannot be seen, to what withdraws. In God and Philosophy, Levinas warns that philosophy tends to assimilate God into Being—as supreme substance, ground, or first cause. But the God he points to is otherwise—irreducible, always escaping the categories of presence, and thus calling the self into a form of attentiveness that is non-idolatrous. Vigilance is what resists that temptation.

So while On Escape still names a frustrated, perhaps even tragic effort to flee from being, later works clarify that this very restlessness was already an ethical stirring. The self’s refusal to rest in being becomes a sign that it is already attuned to something higher, something other—not an idea or an ideal, but a relation: the ethical relation, the face-to-face. That is why, for Levinas, true transcendence is not upward, nor outward, but toward—toward the vulnerable other, whose demand keeps us from closing in on ourselves. Vigilance is not exhaustion; it is responsibility. Not sleep-deprivation, but the refusal to let the Other disappear into the night of the Same. In this refusal, God’s trace remains. This is why, for Levinas, the ethical is the site of the divine. God is not encountered in a mystical union or ontological totality but in the face of the Other who breaks into my world and commands a response I cannot prepare for. Vigilance is this readiness to respond, to remain open to the interruption, even when it costs me my rest, my comprehension, my ontological security. It is a kind of perpetual insomnia—not a deficiency, but a grace: the soul staying up late, because something greater than itself might call, at any moment. In this wakefulness, theology and ethics are no longer separate domains but one: God is not a content of thought, but the condition of responsibility.

In this, Levinas transforms the very structure of transcendence. Where traditional metaphysics sought a way out of finitude through elevation—climbing toward the eternal or the infinite—Levinas reverses the vector. The Infinite comes down, so to speak, and meets me in the finite other, in their suffering, in their voice. Vigilance is the posture that refuses to close the door against this descent. Thus, the escape of On Escape is fulfilled not in metaphysical exit but in ethical exodus: the subject is no longer trying to leave being behind, but to be called out of selfhood for the sake of the Other. That is the miracle: not that one escapes the world, but that one escapes oneself—into service, into witness, into God. “Ethical exodus” names the movement at the heart of Levinas’s project: not a flight from the world into transcendence, but a summons from beyond the self that pulls the subject out of its own enclosure. It echoes the biblical Exodus, but stripped of nationalist or mythic triumph. Here, exodus is not liberation from external bondage alone, but escape from the tyranny of egoism—from the self’s tendency to reduce all others to objects of its comprehension, possession, or indifference. It is an exodus from the Same into the presence of the Other, where freedom is redefined as responsibility before alterity.

In this sense, ethical exodus is not an achievement but an exposure. The subject does not master this movement; it is called, wounded, interrupted. I do not choose to take up the Other’s suffering—it is already on me. The ethical relation tears me from my inertia, from being for-myself, and opens the possibility of being for-the-other without contract, without reciprocity. This rupture is what Levinas calls the Infinite—a trace of God that enters not through revelation in grandeur, but through the unbearable nearness of the Other’s vulnerability. Exodus here is not about destination. It is about departure without return. So ethical exodus is a paradox: to truly leave the self is not to abandon the world but to enter more deeply into it—into its needs, cries, and wounds. To escape is to be sent. Not upward into the divine, but outward toward the neighbor. In this reversal, Levinas transfigures metaphysics into ethics and theology into responsibility. What was once a desperate De l’évasion becomes the infinite demand of Here I am.

The starling—captive, flung against glass—becomes the perfect figure for this condition Levinas articulates: “I can’t get out.” Its wings beat frantically against an invisible boundary. Light pours in, the sky is visible, but there is no passage. This is the paradox of immanence—presence without freedom, visibility without exit. The bird sees what should be liberation, but all it meets is the smooth refusal of transparency. This is Levinas’s “there is” (il y a): existence as an impersonal, overwhelming weight that cannot be undone, only endured. The world surrounds, but does not open. The self finds no door. Yet this image also holds a deeper pathos: the starling is not just trapped—it knows it is trapped. Its struggle is not brute reaction but expressive, almost ethical in its desperation. It yearns. And that yearning is the beginning of transcendence. In On Escape, Levinas does not yet grant this cry a response, but the cry itself—the “I can’t get out”—testifies to the possibility of a beyond. The starling’s pounding is not just despair, it is testimony: that consciousness cannot fully coincide with itself, that being is not enough.

Later, this same structure is transfigured. The glass becomes the face of the Other—not transparent, not passable, but interruptive. It does not let me through, but neither does it let me turn away. It stops me. And that stop, that impossible opacity, is no longer a prison—it is a call. The ethical exodus begins not by shattering the window but by hearing the world through it. The starling’s frantic flight becomes vigilant stillness. I remain. I respond. I am held. I no longer try to escape being—I am taken out of myself by the Other. The starling story is most famously rendered in Laurence Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy (1768), a deeply influential proto-modernist work that blends travelogue, fiction, and philosophical meditation. In one of its most haunting and memorable moments, the narrator, Yorick, visits the Bastille and describes an encounter with a caged starling, which repeatedly cries: “I can’t get out—I can’t get out.”

Yorick is deeply moved. The bird’s cry is not just a mimicry—it is felt. It echoes the human condition, the experience of being trapped in a body, in grief, in bureaucracy, in time. Sterne does not resolve the moment. He lets the starling’s cry linger, and the reader is left with the weight of its resonance. It is no longer just about the bird. It becomes a figure for every soul that has glimpsed a world beyond but cannot reach it—a cry against invisible prisons: confinement, habit, fate, existence. For Levinas, though he never cites the story directly, the sentiment aligns precisely with On Escape. The starling’s refrain—“I can’t get out”—is the very mood of ontological imprisonment Levinas describes. A metaphysical claustrophobia. Not an external tyranny, but a saturation of being that leaves no air. And yet, as in Sterne’s work, that very cry testifies to something more: that there is a “beyond” being sensed, even if not reached. The starling, caged, becomes not just a metaphor for confinement, but a witness to transcendence. Its helpless words expose the crack through which the idea of freedom—of ethical exodus—first enters the scene.

The vigilance Levinas names as ethical wakefulness—the refusal to collapse the Other into the Same, the readiness to respond to what exceeds comprehension—is deeply resonant with the spiritual attentiveness that pervades Rumi and Al-Ghazali. Both see the human condition not as a search for mastery, but as a readiness to be called, touched, transformed. In Rumi, this takes the form of ecstatic longing—the reed flute cut from the reedbed, crying for the return—a constant vigilance of the heart for the Beloved who is never fully grasped, only approached through love, music, and surrender. In Al-Ghazali, especially in The Revival of the Religious Sciences (Iḥyā’ ‘Ulūm ad-Dīn), this vigilance is cultivated through fear, awe, and the purification of intention: a kind of spiritual insomnia that stays alert to divine presence, even in silence, even in suffering. For both, the real escape is not from the world, but from the illusion of self-sufficiency. The trap is not the body or the world, but the nafs—the ego that clings, judges, and veils. True freedom is not escape into flight, but return—to God, to the Real, to the Face. Rumi’s dervish does not flee the world; he spins in it, turning not away but within—becoming a locus of receptivity. This is the same structure Levinas gives to ethical subjectivity: to be taken outside oneself, not by choice but by responsibility, is the beginning of transcendence. Rumi calls this fanā’—the annihilation of the self in love. Levinas calls it substitution—bearing the burden of the other.

In both traditions, then, vigilance is not neurotic attention, but sacred sensitivity: a soul poised, like a reed or a flame, to quiver at the breath of the Infinite. The heart must be trained to stay open, precisely in its breaking. The starling’s “I can’t get out” becomes, in this mystical frame, “I am being held”—and watched. Not by surveillance, but by love. A pluralism that does not collapse into provincialism is a pluralism sustained by attentive encounter rather than accumulation. It does not gather differences as curiosities or decorate itself with borrowed identities. Rather, it allows each tradition, voice, or world to speak from its own integrity—without being folded into a common denominator. This means refusing both universalism that erases difference and relativism that isolates it. It is a way of being with others that neither dissolves them into sameness nor walls them off in alterity. The condition for this is vigilance: a readiness to be transformed by what is not mine, a refusal to reduce the Other to my frame of reference. This vigilance is not abstract tolerance—it is a spiritual discipline. It aligns with what Levinas names as ethical responsibility and what Rumi and Al-Ghazali live as divine attentiveness. It is the kind of pluralism that listens to the voice of the starling crying “I can’t get out”, not as a metaphor to explain, but as a wound to respond to. It requires the humility to be interrupted, the hospitality to let what is foreign remain foreign without making it exotic. And yet, through this shared vulnerability, resonance emerges—not a unison, but a polyphony. A pluralism of rooted flowers, not scattered birds. Each rooted in its soil, open to light, singing not to assert itself, but to reflect the Infinite it hears in the others.

The Book

This being human is a guest house.

Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

some momentary awareness comes

as an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows,

who violently sweep your house

empty of its furniture,

still, treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the malice,

meet them at the door laughing,

and invite them in.

Be grateful for whoever comes,

because each has been sent

as a guide from beyond.

Moses is the figure in whom this tension—between rootedness and transcendence, between particularism and universality—takes on flesh. He is Hebrew, raised Egyptian, fugitive in Midian, then drawn into the impossible call of the burning bush: a voice that speaks from within fire yet does not consume. Moses is, in this way, the paradigm of ethical exodus: not simply one who leads a people out of bondage, but one who is himself drawn out—from privilege, from silence, from self-sufficiency—into radical responsibility. His first answer to God is not confidence but trembling: “Who am I that I should go?”—the cry of one who senses that true mission comes not from possession of power but from a wound, a break, a summoning. He is also the lawgiver who never enters the land. This is not just a narrative twist; it is a theological axiom. Moses must remain on the mountain, between heaven and earth, with his face veiled—not because he hoards the divine, but because he cannot collapse God into presence. Like Levinas’s subject, he stands before the infinite, not as a knower but as a listener, a servant, a translator who stutters. His tongue is heavy, and yet he becomes the mouthpiece—not of totality, but of a law that insists on the dignity of the stranger, the orphan, the slave. Moses is not the founder of a nation-state; he is the bearer of a relational law—one that encodes vigilance, memory, and the refusal to forget what it means to have been Othered. Moses, then, is the hinge between pluralism and revelation. He receives the Word not to enclose it but to hold it open—inscribed on tablets that must be shattered if they become idols. His legacy is not possession but passage: he gives a law, a path, a name—but not a home. He leads, and he watches from afar. In this, he becomes not only the prophet of Israel but the patron saint of all who live between worlds, drawn by a voice that says: “Remove your sandals, for the ground you stand on is holy.” Holy—not because it belongs to you, but because it summons you beyond yourself.

Jesus stands as the radiant inversion of possession—God not enthroned in power, but emptied into flesh, into vulnerability, into the face of the Other. Where Moses receives the law carved in stone, Jesus embodies it as flesh and wound: the commandment to love not as obligation, but as presence. He does not dissolve the law but fulfills it—by walking into the margins, touching lepers, forgiving traitors, turning his cheek not to prove moral superiority but to unveil the sheer excess of divine hospitality. In Jesus, the ethical exodus becomes incarnation—God’s own escape from transcendence into the finite, not to dominate but to be exposed, to be received, or rejected. He speaks not in systems, but in parables—forms of ethical pluralism, in which meaning is always near, yet never forced. Jesus does not conquer difference, he dwells in it. Samaritan, Roman, prostitute, Pharisee—each becomes a site of divine encounter, not by conformity but by reversal. The kingdom he proclaims is not a homeland, not a closure, but a seed, a yeast, a pearl—a hidden radiance demanding vigilance. His presence disorients the logic of exclusion and purity: the first are last, the meek inherit, the crucified is crowned. On the cross, Jesus is the starling: “I can’t get out.” And yet—he doesn’t. He stays. He absorbs the full weight of the il y a, the suffocating presence of forsakenness: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” This is the exodus beyond even escape—the ethical descent into solidarity with the abandoned. And in that descent, he becomes the trace of the Absolute within the broken. Not triumph over death, but witness through it. The resurrection is not a reversal of vulnerability, but its transfiguration: the wound remains, but now it shines. Jesus does not erase difference—he bears it, blesses it, and leaves space in his body for the Other.

Muhammad, peace be upon him, is the seal of prophethood—not as the closure of divine speech, but as the completion of its relational arc. He is not merely a messenger who delivers a final text, but a man whose life becomes the embodied echo of divine mercy: “We have not sent you except as a mercy to all worlds.” Like Moses, he receives revelation; like Jesus, he lives it; but unlike either, he becomes its integrator—a prophet whose mission is not escape from history, but its ethical transformation. His pluralism is radical monotheism—a unity so vast it dignifies the diversity of creation, not by erasing it, but by calling each thing to bear witness to the Real (al-Ḥaqq). The Qur’an repeatedly names difference—of language, nation, law—as signs (āyāt) of God. Muhammad does not collapse the many into the one; rather, he orients the many toward the One. He receives not a private revelation, but a public one, open to time, politics, law, and community. Yet even here, he maintains the prophetic posture of vigilance: long nights in prayer, deep humility before verses that come “by the angel’s weight,” tears at the plight of his people. He is madīna, city; ummī, unlettered; ḥabīb, beloved—at once intimate and universal. His sunnah is not domination, but disposition (khuluq): to respond with gentleness when opposed, to bow when praised, to forgive where vengeance is easy. And like the starling, there is a moment of “I can’t get out” in his life too: in the cave of Ḥirāʾ, gripped with terror at the first revelation; during Ṭāʾif, bloodied and rejected; and in the hijrah, his exodus from Mecca—not an escape from suffering, but a passage into deeper trust. Muhammad’s pluralism is not passive tolerance, but responsible stewardship—the building of a community (ummah) where the orphan is central, contracts matter, and even enemies are humanized. And though he is the final prophet, his message is not finality—it is return: to God, to justice, to the fitrah, the deep-rooted nature planted in every soul. He is, like the flower, rooted—yet his presence opens the whole world to bloom.

The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States, crafted by the Founding Fathers, represent an attempt to enact a new political form of ethical exodus: a departure from tyranny not simply to escape, but to found a new order grounded in liberty, law, and responsibility. The Declaration begins with a metaphysical claim—that “all men are created equal,” endowed with inalienable rights by their Creator—and in doing so, frames politics not as a mere contract of mutual interest, but as an appeal to a moral law higher than kings. It is a rupture, like Moses’ flight from Pharaoh, framed not merely as rebellion but as testimony: that there is a limit to power, and a dignity in man that transcends historical status. But the Constitution shifts registers: it is not rupture but reformulation, not flight but formation. It attempts to transform the ethical cry of freedom into durable structure—a pluralism of federated states, checks and balances, competing voices held in dynamic tension. It is an architecture of vigilance. It does not presume unanimity; rather, it encodes disagreement, as if aware that truth in a pluralist society cannot be imposed but must be contended with, negotiated, protected. The Bill of Rights, like the Qur’anic emphasis on the dignity of the soul, restricts power not to weaken government but to protect the sacredness of the Other—speech, conscience, assembly, difference. Yet this founding is also deeply paradoxical. Like Moses striking the rock in frustration, the Founding Fathers proclaimed universal liberty while many held slaves. The pluralism they designed was provincial in practice—excluding women, Indigenous peoples, the enslaved. And yet, in the very tension between their ideals and failures, a prophetic core remains: a text that accuses its authors. The Declaration and Constitution become American scripture not because they are flawless, but because they are unfinished—inviting continual rereading, reinterpretation, ethical vigilance. They are like shattered tablets, preserved not to enshrine perfection but to remind a nation of what it has not yet become.

For Derrida, justice is not a fixed principle, nor a codified outcome—it is what exceeds the law, haunts it, and calls it into question. The law is constructed, historical, conditional—it must be made, interpreted, enforced. Justice, by contrast, is infinite: it cannot be fully realized or present as such, but is always à venir—to come. This phrase, à venir, is crucial: justice is not what we possess, but what we approach, what interrupts and unsettles every legal form from beyond. It arrives like the Other in Levinas: unanticipatable, irreducible, unprogrammable. And so the law is always in need of deconstruction—not destruction, but an opening up, a displacement toward that which the law cannot enclose. Derrida reverses the typical hierarchy: law is not the source of justice, but its imperfect vessel. Law can become rigid, institutional, blind. Justice, by contrast, is listening—to the singular, the exception, the unheard, the untranslatable. And because no law can capture all the voices, all the contexts, all the suffering that asks for redress, law must be interrupted, opened from within by a responsibility that comes from elsewhere. This is why Derrida often links justice not to rights or procedures but to hospitality—the ethical act of welcoming what is strange, unprepared-for, even threatening to the self’s stability. To be just is not to follow the law, but to listen beyond it. Thus, deconstruction is not relativism—it is care: a restless, meticulous attention to what the law forgets, marginalizes, or suppresses in the name of order. Justice is the name for that which law seeks, but can never fully attain without betraying its form. The law must be made, but never idolized. It must be applied, but never assumed as complete. Like the face of the Other in Levinas, justice calls not from within the system, but from the place where the system fails. This is why justice is always to come: not because it is delayed, but because it is in excess—an impossible demand we must answer anyway.

America, at its most aspirational, can be read as an attempted analog technology of ethical exodus: not merely a geographic or political escape from monarchy, but a metaphysical act of founding grounded in the idea that humans could live according to conscience, covenant, and deliberative plurality. The very act of “declaring independence” was a performance of ethical rupture—a stepping out from under inherited authority into the difficult terrain of self-governance. This was not escape in the escapist sense, but escape into responsibility, into the burden of freedom. Like the Hebrews fleeing Egypt, like the Prophet migrating to Medina, the Founders imagined a people not just leaving, but becoming: becoming accountable to a law they themselves must wrestle with. The technology of this ethical exodus was the Constitution—an engineered framework meant to contain power through division, preserve dissent through the First Amendment, and institutionalize vigilance through checks and balances. It is a design that presumes fallibility, contingency, and the necessity of correction. In this sense, America was not founded on the idea of a completed truth, but on the possibility of an incomplete justice—one that must be approached, not possessed. This is what links it, conceptually, to Derrida’s justice-to-come: a structure always under revision, haunted by the gap between its promises and its enactments. And yet, this analog remains fragile. From the beginning, the gap between the universal ideals and their provincial applications—enslavement, genocide, exclusion—threatened the legitimacy of the project. But this does not negate the ethical aspiration; it sharpens it. It means the American exodus, if it is to be real, must be perpetual: not a one-time act of liberation, but a recurring commitment to repair, to listening, to being interrupted by the Other—the poor, the enslaved, the immigrant, the dispossessed. The greatness of the American project is not in its perfection, but in its capacity to be pierced by its own unrealized ideals.

When America commits—even imperfectly—to this analog technology of ethical exodus, it creates the conditions for unprecedented cultural and technological flourishing. Ethical exodus is not just a political departure from tyranny; it is also a spiritual architecture that generates room: room for dissent, for multiplicity, for invention. By framing law not as divine decree but as deliberative covenant, and justice not as possession but pursuit, the American experiment made space for the creative tensions that animate both democracy and innovation. Its founding paradox—freedom bound by law—mirrors the generative tension of all creative work: structure and improvisation, rootedness and experimentation, difference held in shared time. This fertile tension spills into the arts, into literature, into music—jazz, for instance, is America’s sonic model of pluralism: rooted in suffering, born in exile, structured yet always escaping. So too, the Harlem Renaissance, Transcendentalism, Modernism, all emerge from the same civic soil that enshrined freedom of speech, religion, and press. Culture flourishes where vigilance is enshrined, where people are free to dream otherwise, to tell stories that challenge the state, to build identities that defy inheritance. These are not accidents of the Enlightenment—they are its embodied resonance. Technological flourishing follows the same arc. The constitutional order’s implicit ethic of open systems—federalism, experimentation, revision—parallels the logic of scientific inquiry. When a people are taught to distrust fixed authority and build through distributed intelligence, they eventually produce the internet, microprocessors, open-source code, and spaceflight. The First Amendment is not just a political principle—it is the software of technological innovation: freedom to think, to fail, to remix, to iterate. The ethical exodus becomes an epistemological one—liberating inquiry from priesthood and placing it in the hands of communities. The burst of technology is not separate from the ethical vision; it is its acceleration. When vigilance, plurality, and responsibility are structurally encoded, the culture doesn’t just survive—it blooms and builds.

The work is not America’s possession, but America’s calling. Even if America as a state were to fall—its institutions corrupted, its people scattered, its promises betrayed—the template it reached for remains necessary: a covenantal structure for holding together radical difference without domination, and for responding to the infinite demands of justice without closure. That aspiration, once declared, cannot be undeclared. It haunts the future. It sets the terms of any successor: you must build in such a way that freedom remains responsive to the Other, that law remains open to revision, that power remains checked by memory and conscience. If America collapses, it will not be because the ideal was false, but because the vigilance required to sustain it was abandoned. The continuity of this work demands something like America—not in flag or frontier, but in form: a political theology that turns exodus into structure, justice into method, and pluralism into law. This something-like-America must preserve the sacred instability of the original design: its refusal to totalize, its permission for dissent, its porousness to the unheard. It would not need to call itself America, but it would have to hear the same cry—the starling at the window, the enslaved in the fields, the child in the cage, the dissident at the podium. It would need a constitution capable of listening. This is the real legacy—not a geography, but an attunement: to build order without oppression, to bind difference without absorption, to name the universal without erasing the particular. The fall of America would be a tragedy only if it closes that listening. But if it becomes compost—if its ruins feed the soil of a new, vigilant, plural structure—then even its death could be part of the exodus. Not an end, but a shedding. The burning bush still speaks. Who will answer?

America, you were never meant to be a place. You were meant to be a promise. A living covenant. A wager that a people, bound not by blood but by belief in the dignity of all, could craft a society where freedom did not mean dominance, where power bent toward justice, and where strangers could become neighbors without being made the same. From the start, you have failed this promise—and yet you have not forsaken it. Your founding documents are not relics; they are ruptures. They cry out. They accuse you. They say: you wrote these words—all men are created equal—while bodies were in chains. You claimed liberty while lands were stolen. And still, the words endure, because they were never fully yours. You carried them, but they carried you. Now, again, you are trembling. You feel the tremors—division, cynicism, cruelty dressed up as pragmatism. You feel the heat of a world catching fire. You are afraid. Some say the promise is dead. But I tell you: promises don’t die—they wait. They linger. They haunt. And they ask you, in every generation, will you be faithful this time? Do not mistake nostalgia for patriotism. Do not mistake victory for virtue. Do not mistake silence for peace. What made you great was never your power. It was your attempt. Your willingness to risk yourselves on the belief that people can govern together without tyranny, without erasure. That we can listen—to the Other, to the broken, to the not-yet-born—and be changed. Even if you fall, the work must go on. But why should you fall? Why should the starling remain trapped, when you already heard its cry? You built something no empire has built: not dominion, but a platform for difference—fragile, unfinished, sacred. So rise—not in triumph, but in attention. Rise in repentance. In revision. In re-commitment. Be again what you’ve never quite been but always might be: a nation not of possessions, but of promises kept. A nation not of walls, but of welcoming vigilance. Justice is still to come. Will you listen? Will you make space for it? Will you stay awake? America, do not go back to sleep.