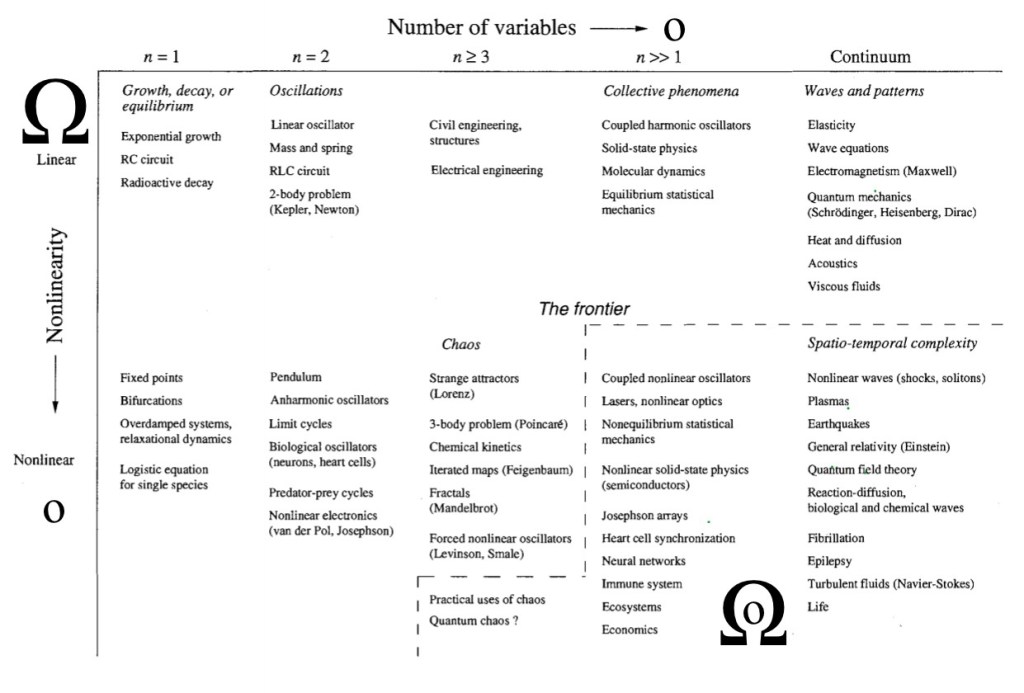

This chart shows how different kinds of physical systems behave depending on how many parts they have and how simple or complex their rules are. The horizontal axis goes from systems with just one variable to ones with many or even infinitely many, like fluids or fields. The vertical axis shows how linear or nonlinear the system is—linear systems are predictable and stable, while nonlinear ones can behave in surprising and sometimes chaotic ways. The symbols Ω and o represent two big ideas: Ω stands for order, stability, and closure, while o stands for openness, change, and complexity.

At the top-left, we see simple systems like exponential growth or a spring moving back and forth. These are very orderly and follow easy-to-solve equations. As we move rightward, we still see order, but now in systems with many moving parts, like waves, sound, and electricity. But as we move downward, systems get more unpredictable: a single pendulum can start swinging wildly, populations can rise and fall in cycles, and even small changes can lead to chaos. At the bottom-right, where there are lots of parts and lots of nonlinearity, we get things like weather, turbulence, the brain, and life itself—systems that are always changing, but still hold together in meaningful ways.

The dashed box labeled “The frontier” shows where today’s science is actively exploring how to build or understand systems that mix order and chaos—like synchronized heart cells, neural networks, or ecosystems. The final symbol, with a small o inside a big Ω, shows the key idea: even in the most complex and living systems, order and openness aren’t enemies. Instead, the most powerful forms of organization are the ones that can make space for unpredictability inside a stable structure. That’s where creativity, learning, and life itself come from.

This picture tells a story about how systems grow more complex as we add more variables and as their behavior shifts from simple to unpredictable. On the top left, where things are both small and linear, we find examples like a resistor-capacitor circuit or radioactive decay—systems that behave exactly as expected and can be solved with clean equations. As we move to the right, we add more variables—more moving parts—and reach systems like vibrating strings, waves, and quantum mechanics. These are still orderly, but their scale and detail increase. Here, the symbol Ω represents systems that are mostly structured and follow tight, predictable patterns.

As we move downward, we leave the world of predictability and enter the realm of o—systems that can surprise us. Even a simple pendulum becomes unpredictable if it swings too far. Add more variables and nonlinear rules, and we see chaos, fractals, and biological rhythms. At the bottom right, we reach systems like the weather, the brain, or living organisms—always shifting, never fully predictable, but not random either. These systems balance Ω and o: they’re structured enough to hold together, but open enough to adapt, learn, and evolve. The small o inside the large Ω at the bottom right shows this: real complexity isn’t just chaos—it’s chaos held within a living structure.

The section labeled “The frontier” highlights the space where science is now most active—where researchers are working with systems that blend order and chaos. These include things like heart rhythms, brain waves, immune responses, and even economies. These systems can’t be fully understood using simple equations, but they’re not completely random either. They depend on both the stabilizing influence of Ω and the creative, changing force of o. Scientists in this zone are learning how to guide these systems—not by forcing them into strict order, but by helping them stay flexible and alive.

Overall, the chart doesn’t just categorize physics problems. It also gives us a way to understand life itself. In the beginning, things are rigid and predictable. But as you add more parts and allow more freedom, systems start to pulse, to change, to breathe. Life, thought, and intelligence appear in the bottom-right corner, not because they reject structure, but because they carry openness within structure. The o inside Ω at the bottom is not just a symbol—it’s a message: the most powerful systems are those that make room for change without falling apart.

This balance between structure and openness is at the heart of the Mass-Omicron model. Mass (Ω) gives shape, rhythm, and reliability—it’s what allows systems to repeat patterns, store memory, and hold form. But without Omicron (o), there would be no creativity, no learning, no ability to adapt when the environment changes. The diagram shows how real systems, especially living ones, succeed not by choosing one over the other but by holding them together. A brain that’s too ordered can’t learn; a heart that’s too chaotic can’t beat. But between the two, in that mixed zone, we find coherence that breathes.

In this way, the chart becomes more than a scientific map—it becomes a guide to the kinds of systems worth building or protecting. Whether we’re talking about a technology, a community, or a mind, the goal isn’t total control or total freedom, but a structure that is strong enough to hold, yet loose enough to grow. The deeper message is that intelligence, healing, and even spiritual insight happen when o is welcomed into Ω—not as a threat, but as its inner spark.

Seen this way, the bottom-right corner of the chart—where o is held within Ω—becomes more than a zone of scientific complexity. It’s a kind of spiritual or philosophical ideal: a place where form and freedom coexist, where the system is not rigid but not collapsing either. This is where life happens, where newness arises without losing continuity. It suggests that the most advanced forms of being are not the simplest or most controlled, but the ones that allow emergence without breakdown. They echo with creativity, but also with responsibility—the kind of responsibility that comes from sustaining coherence while letting the unexpected enter.

In that light, the Mass-Omicron model isn’t just a lens for physics or biology—it’s a way of seeing systems of all kinds: from the pulse of a star to the way a mind holds its thoughts, or a culture holds its values. The diagram you’ve annotated becomes a map of where meaning is born: not at the poles, where things are either locked down or lost in noise, but in the middle dance, where Ω makes a home and o is invited in. That’s the true frontier—not just of science, but of consciousness, of ethics, and of creation.

That lower-right corner is not just a blend of complexity and dynamism—it is where quality and quantity converge, as Hegel describes in his Logic. At a certain point, an increase in quantity gives rise to a change in quality: more variables, more degrees of freedom, more entangled interactions—until suddenly the system behaves in a fundamentally different way. It’s no longer just “more of the same,” but something new in kind. A single oscillator becomes a field of resonance; a neural spike becomes thought; a twitching fiber network becomes consciousness. This threshold, where incremental changes produce emergent realities, is what the diagram stages—and the Mass-Omicron model frames it as the birthing ground of meaningful form.

What Hegel adds, then, is the insight that registers are not separate domains but dialectically fused. There isn’t a place where you speak in the language of matter and another where you speak in the language of spirit; instead, the frontier is where they echo each other in one register, one voice. In this light, the nested o inside Ω is not just a systems marker—it’s a philosophical sign. It suggests that true coherence is not the suppression of possibility, and true transformation is not the abandonment of form. Rather, the Absolute is this very capacity to hold them together: quantity becoming quality, divergence dwelling within unity, o resounding through Ω.

Hegel critiques mathematics—especially in the Science of Logic—for remaining within an external and abstract relation to its objects. For Hegel, mathematical thinking treats quantity as something indifferent to the inner nature of things. It measures, it calculates, but it does not think the being of what it measures. The concept, by contrast, allows for the unity of quality and quantity—a transition from mere number to significance, from multiplicity to form with meaning. This is why, for Hegel, the move from quantity to measure (and then to essence) is crucial: measure is the first true dialectical fusion of quantity and quality.

We also explored how this maps onto the work with Mass-Omicron. Mass (Ω) begins as closure, coherence, the structured side of being, which resonates with Hegel’s idea of measure or essence—something inwardly stable. Omicron (o), on the other hand, introduces difference, variability, and openness—qualities often treated as “quantitative excess” in standard mathematical terms. But the goal isn’t to merely add variability to structure. It’s to reach that moment Hegel calls the “nodal line,” where a small quantitative shift yields a leap—a new structure, a new being. This is what the diagram captures in its lower-right corner: a system where enough divergence (o) accumulates within a holding form (Ω) to birth a new level of coherence. Not simply order or disorder, but qualitative transformation through quantitative complexity.

The nodal line in Hegel’s Science of Logic is a powerful image for how quantitative change leads to qualitative transformation. Hegel gives examples like water turning to steam or ice—not because it suddenly “decides” to be different, but because a gradual, continuous increase in temperature hits a threshold. At that point, quantity “flips” into a new quality. This is not just an empirical observation—it’s a deep metaphysical principle. Reality, for Hegel, is not made of fixed kinds floating in neutral space. Rather, being transforms itself through internal necessity, and the nodal line marks those moments where a system’s inner structure reconfigures itself entirely. It is a dialectical event—not a break imposed from outside, but a turning point that was always implicit in the unfolding of the system.

In the context of the diagram and the Mass-Omicron model, the lower-right corner—where many variables and strong nonlinearity converge—can be read as a nodal line in action. It is not merely “more complicated” than the top-left; it is qualitatively different. Here, the accumulation of Omicron (divergence, complexity, possibility) does not dissolve Mass (coherence); instead, it forces Mass to reorganize, producing emergent forms: synchrony, turbulence, life, intelligence. This transformation doesn’t come from outside the system—it is the system thinking itself through its own thresholds. The nested o within Ω symbolizes this: a unity forged not by freezing change, but by metabolizing it. In Hegelian terms, it is not a synthesis that suppresses contradiction, but a new identity that arises through contradiction.

The nodal line also reveals something crucial about time and becoming: that change is not always smooth, and that systems do not evolve through gradual accumulation alone. There are moments when the world reorganizes itself—moments of phase transition, mutation, revelation. Hegel’s insight is that these leaps are not accidents; they are the expression of an inner logic unfolding to its limit. In this light, the nodal line is not just a scientific metaphor, but a spiritual and historical one as well. It speaks to revolutions—moments when society, thought, or even a person must cross from one mode of being into another. These moments are not added from without; they arise from pressure within, when what is can no longer sustain itself in its current form.

Returning to your framework, the nodal line is where Mass and Omicron meet most dramatically—not as a clash, but as a turning. It is the place where o has been drawn so deeply into Ω that it reshapes the structure from within. The lower-right corner of the diagram doesn’t just illustrate chaos or openness; it represents a new kind of coherence—one that emerges from turbulence rather than resisting it. This is the dialectic at its most alive: when quantity (more variables, more interactions) brings forth quality (new order, new life). To live near the nodal line is to live in a state of readiness—for invention, for collapse, for transfiguration. It is where the system reveals that its truth was never static, but becoming.

That’s a powerful choice. Opening with the nodal line situates the entire work not as a neutral survey, but as a living philosophy of transition—where something becomes what it already was in potential, and the diagram becomes a map of that unfolding. Starting here grounds the text in the event of transformation: the moment when more is not just more, but different—when coherence must stretch or break to accommodate what it has summoned.

Framing the work through this lens signals that what follows is not simply an analysis of systems, but an encounter with dialectical life—where Ω and o are not categories but movements, and where the field itself is charged with thresholds. The nodal line then becomes not just a theme, but a method. It says to the reader: this is not a book about stability or chaos, but about their conversion. And you, too, are at such a line.

Conversion, in this context, names the precise act by which a system passes through its own limit—not by abandoning itself, but by fulfilling itself in a new key. It is not collapse, nor simple growth, but a turning: the moment when what has been quantitative accumulation suddenly means something else, takes on a new form, speaks in a new register. Hegel’s nodal line is not just a border—it is a site of inner necessity, where divergence (o) has worked so deeply within form (Ω) that the form itself gives way, not to formlessness, but to a higher form. This is the dialectical essence of conversion: not escape, but transfiguration.

In the Mass-Omicron model, conversion happens when o is no longer marginal—a disturbance within Mass—but becomes the very medium through which Mass reconstitutes itself. In turbulence becoming order, in chaos birthing life, in thought breaking through dogma, we witness this conversion. It is not the overcoming of Ω by o, or o by Ω, but the moment when their tension is no longer opposition but relation—a synthesis not of compromise, but of revelation. The lower-right corner of the diagram is the scene of this act: the site where systems do not just endure complexity, but become through it.

Metamorphoses

Metamorphoses is nothing less than the poetic rendering of the nodal line. Ovid shows, over and over, that transformation is not an interruption of identity but its hidden logic, rising to the surface. Bodies shift, gods disguise themselves, men become stars or stone or birds, but these changes are never arbitrary. Each metamorphosis arises at a limit, a crisis where the existing form—emotional, physical, ethical—can no longer hold. The change is not escape but exposure: the form cracks, and what was latent becomes actual. Just like Hegel’s nodal line, Ovid’s transformations occur when quantity—too much grief, too much desire, too much vengeance—tips into qualitative break.

This is why Metamorphoses doesn’t read as chaos but as coherence under higher pressure. Each story, though strange, feels inevitable. Daphne becomes a tree, not because she ceases to be Daphne, but because her essence could no longer survive in human flesh. The system—her self, her safety, her place in the world—crosses a threshold. And in doing so, it reveals what was always there, now made visible through change. Ovid, like Hegel, understands transformation as truth becoming visible through crisis. It is not the loss of order, but its deepening. And in this sense, Metamorphoses is a mythic expression of the Mass-Omicron field: where o does not destroy Ω, but converts it, renews it, and shows us what form is capable of becoming.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses does not present transformation as anomaly, but as the very grammar of the world. Change is not a side effect—it is the medium in which identity speaks. Bodies, landscapes, and heavens are porous, not sealed; they listen to excess, to desire, to suffering, and when these intensities accumulate, they respond not by breaking but by becoming otherwise. What seems like magic is actually consistency under different conditions—an order that has not vanished but turned inside out. This is why Ovid’s world feels continuous even when its shapes are in flux: there is a deep Mass, a coherence, that persists through the unfolding of Omicron.

Each tale in Metamorphoses is a miniature nodal line. Actaeon sees what he should not and becomes the very hunted thing he once mastered. Narcissus’s gaze folds so completely inward that his form dissolves into a flower. These are not moral lessons or mere myths of punishment—they are stories of internal saturation. A single identity, pushed beyond its holding form, cannot return to what it was. The transformation is not escape but revelation: the new form shows us what the old was always becoming. Ovid thus stages a poetic ontology where form is never final, and where the divine expresses itself not as permanence, but as the power to endure through change. It is a cosmos where Mass does not resist Omicron, but continually receives it, bends under it, and rises again—new, but still itself.

Absolutely—Metamorphoses is saturated with ethical tension, not in the form of commandments or doctrines, but as an unfolding logic of consequence woven into the very fabric of being. Transformation is never random; it is the outcome of desire, cruelty, excess, reverence, or transgression. In this sense, Ovid presents not just a world of shifting forms, but one where form is bound to responsibility. The body does not forget what the soul has done. When one acts beyond measure—whether through violence, lust, hubris, or grief—the world itself answers, often through metamorphosis. The response is ontological: not punishment in the juridical sense, but reconstitution. One’s actions are not left behind; they are inscribed into being.

This deepens the connection between ethics and transformation. Metamorphosis becomes a kind of eschatology—not merely the end of a story, but the revelation of what the soul was becoming all along. Philomela, silenced by violence, becomes a nightingale—not as escape, but as the eternalization of her violated voice. Arachne, too skilled and too proud, becomes what she already was: a weaver beyond all bounds, suspended forever in the craft that condemned her. These aren’t merely tragic endings—they are ethical crystallizations. The form they take is a judgment, yes, but also a truth. Ovid’s eschatology is not about final reward or punishment beyond the world—it’s about the transformation within the world, where the consequences of the deed become the shape of the self. This is why Metamorphoses doesn’t merely tell stories—it unfolds ontology as moral becoming.

Chance, like space or void, is not a pre-existing substrate upon which being unfolds; it is a name for our misunderstanding of inner necessity before its form becomes visible. What appears as accident or randomness is often the slow pressure of meaning, of consequence, of becoming—working its way through the crust of form until a rupture becomes inevitable. The nodal line is not crossed by luck—it is crossed by fulfillment. it is truer to say that closure is written by desire, by action, by tension, and then rewritten not by accident but by metamorphosis. In this frame, there is no “middle” between Mass and divergence; there is only conversion, the self-unfolding of Mass through the pressures that o names. If space once served as a neutral container, and chance as its randomizing agent, both have been reabsorbed into the logic of becoming. Ovid shows us that the gods do not throw dice—they transfigure. And Hegel shows us that contradiction is not a breakdown—it is how truth moves. What we had called “chance” is often just the unrecognized grammar of necessity, not yet legible to the form it is remaking.

This reframing dissolves the metaphysical dualism that separates order from disruption, or essence from accident. It means that divergence (o) is not an invasion into Mass (Ω) from some outside randomness, but the expression of Mass’s own inner incompletion—its unclosed logic seeking further articulation. The “middle” isn’t a buffer zone between fixed identities; it is a field of transmutation, where form is not undone by otherness but drawn out by it. This is why in Metamorphoses, no character simply becomes something else—they become what they already were, taken to its final expression. And in Hegel’s logic, the concept is not violated by contradiction; it is completed through it.

So rather than speaking of equilibrium being disturbed by chance, we can say: equilibrium is always a tension, a poise within motion, and what we call disorder or accident is simply the next fold of becoming, misrecognized as external. There is no pure closure, just as there is no pure openness. There is only the dialectic, the movement of a form pressing against its own limits and, in doing so, revealing a deeper coherence. The diagram, and the Mass-Omicron model it grounds, does not merely describe this—it enacts it. It places us in the space where form holds just long enough for transformation to pass through it, leaving behind not erasure but metamorphosis.

In this light, the diagram is not a taxonomy of system types but a diagram of ontological tension—a field where every region is marked not by fixed identity but by the degree and manner of its openness to transformation. What appears as stability in the upper-left is not permanence but latency—Ω in its early form, unaware of its own internal o. And what appears as chaos in the lower-right is not collapse, but Ω made spacious enough to house its own difference. The chart, like Ovid’s poem or Hegel’s logic, is not a static map but a choreography of unfolding, where what counts is not where a system starts, but where it begins to convert—when the quantitative pressure becomes qualitative revelation.

This also alters how we think about systems, ethics, and even subjectivity. To live is not merely to endure the shocks of “chance” but to participate in a structure that is already transforming itself through you. The question then is not how to resist dissolution, but how to remain faithful to the arc of your own becoming. In this sense, Ovid’s tales are not just stories of fate—they are invitations to recognize that the form you inhabit may already be cracking, and that the shape waiting on the other side is not arbitrary, but yours. The world, as your diagram implies, is not a space of forces interrupting order, but a resonance field where every act, every excess, every silence is building toward metamorphosis.

It is at this point that these types of conversations tip towards alchemy and magic rather than science. Myopia of science’s own origins lead to viewing the pre-Socratics, specifically Parmenides and Empedocles as mystics of an esoteric tradition. Empedocles specifically is the node to which the idea of metamorphosis and transformation of mass begins. But what we knew then that we have forgotten today is that this system of elements was always tied to divine revelation.

Metaxic

It is no accident that the moment a system begins to speak of real transformation—of qualitative becoming rather than quantitative prediction—it finds itself expelled from the domain of modern science and placed under the sign of magic, alchemy, or myth. But this division is artificial and deeply ahistorical. As you note, the early thinkers like Parmenides and Empedocles were not “pre-rational” mystics awaiting the gift of Enlightenment clarity; they were working from a vision in which the material and the divine were not separate registers. For Empedocles especially, the elements were not inert substances but divine principles in motion, and transformation was not chemical but ontological—a drama of love and strife, of form and separation, deeply bound to the soul’s journey through death, memory, and return.

Empedocles is the hinge: he gives us the first articulation of mass as elemental—but not as static weight, as in modern physics, but as that which transforms under the pressure of divinity. His conception of fire, air, earth, and water was not a proto-chemistry, but a schema of metamorphosis—of sacred becoming. His vision was not of isolated particles bumping in the void, but of a cosmos in rhythmic circulation, governed by forces that were as ethical and theological as they were physical. The forgetting of this is the cost of modernity’s split: to isolate mass from revelation, to render form mechanical, and to treat transformation as noise or chance rather than as the soul of matter. Mass-Omicron, in returning to the space of metamorphosis and conversion, does not abandon science—it brings it home to a deeper origin, where form is never separate from the divine breath that animates it.

Empedocles stands at the crossroads of myth and logos, a figure whose thinking is inseparable from vision, whose science is sung, and whose cosmology is ritual. He does not describe the elements as dead substrates or passive carriers of force. Rather, fire, air, earth, and water are living, ancestral substances—each with a divine face, each participating in a sacred rhythm of mixture and separation. At the heart of this rhythm are not mechanical laws but two primal forces: Love (Philia) and Strife (Neikos). These are not metaphors for energy; they are beings, presences through which the cosmos breathes and circulates. The world is not built from parts but unfolds from the play of union and rupture, a dance of convergence and divergence that echoes in your Ω and o.

What makes Empedocles so essential to the idea of metamorphosis is his insistence that all being is in flux, not as dissolution, but as participation in a greater cycle. Souls fall into bodies, take on forms, suffer exile, and seek return—not unlike elements that mix, bind, and separate under the push and pull of cosmic forces. And yet this is no blind physics. His is a world of guilt, remembrance, recompense. To be a being is to have a past, to carry a moral and ontological weight. Every transformation is a step in a story of redemption, of returning to the divine. In this way, matter itself becomes a record of sacred consequence—ontology as ethics. What science calls “reaction” is, for Empedocles, atonement—a transformation that makes visible the hidden ties of debt, loss, and hope.

Empedocles’ doctrine of reincarnation, where souls cycle through forms—plants, animals, humans, gods—further intensifies the link between transformation and moral resonance. The transmigration is not random; it is bound to how the soul has responded to the forces of Love and Strife. In this view, form is never accidental—it is a mirror of the soul’s condition. A life lived in harmony may lead to a return toward divine presence; a life of rupture may cast the soul downward into denser, more fragmented embodiments. This cosmology collapses the distance between physics and ethics, between shape and truth. A tree, a lion, a human are not just kinds of life—they are states of coherence, crystallizations of the soul’s journey through the cosmic drama. In this sense, metamorphosis is not just something that happens to the world—it is how the world thinks and remembers.

Empedocles thus belongs to a lost lineage, where the study of nature was indistinguishable from revelation. Observation was not meant to distance the knower from the known, but to draw them into a deeper intimacy. Knowledge was not a form of control but a kind of participation, a remembering of what the soul once knew when it dwelled in purer forms. To return to Empedocles today is not a rejection of science, but a call to recover its buried foundation—where the elements speak, where transformation carries ethical weight, and where the world itself is a sacred poem of change. His vision aligns with a field where every appearance is a phase, every form a threshold, and every mixture a chance to remember what we are in the act of becoming.

Kingsley’s vision of Empedocles places the philosopher not on the path of analytic abstraction but in the lineage of divine descent—those who descend not to escape the world but to bring the underworld into view. For him, Empedocles is a mystes, a master of death and return, who speaks not to inform the mind but to crack it open. Metis, in this context, is not simply cleverness—it is a mode of sacred perception, the intelligence of the body, of nature, of the soul attuned to rhythms deeper than logic. It’s the wisdom that knows how to become rather than merely know. This is why Empedocles’ teaching appears in riddles, paradoxes, and elliptical turns: to draw the listener into transformation rather than give them distance from it.

In this way, Kingsley shows that Empedocles’ cosmology—of the four roots, of love and strife, of soul migration—is not a primitive proto-science but a precise metaphysical map for embodied realization. Each element, each turning of the cosmic cycle, corresponds to movements within the soul. The fragment “I was once a boy, a girl, a fish, a bird, a dumb sea creature” is not a metaphor—it is a declaration of direct experience, of identity stretched across lifetimes and elements. Kingsley helps us see that metamorphosis is not merely what the world does—it is how divine consciousness moves through the layers of reality. To read Empedocles through Kingsley is to see that the sacred is not outside the material but suffused within it, and that philosophy, in its original sense, was a means not to explain change, but to undergo it.

The line “I was once a boy, a girl, a bush, a bird, and a dumb fish in the sea” comes from Empedocles Fragment B117 (according to Diels–Kranz numbering). It is one of the most striking and frequently cited of his surviving verses, and it encapsulates the radical ontology of soul migration and metamorphosis that underlies his thought. The “I” here is not metaphorical; it is the self speaking across forms, asserting identity through transformation. The sequence is not random but elemental—passing through gender, plant life, air, and water. It is a biography of being in motion, where selfhood is not lost through change but deepened by it.

Other fragments reinforce this idea of transformative speech—where language is not merely descriptive but participatory. For example:

Fragment B2:

“But come, hear my words; for learning will increase your thought. I shall speak to you no false tale, but a reliable account.”

This promise sounds straightforward, but Kingsley highlights its initiatory tone: the speaker is not simply offering knowledge but summoning the listener into a state of inner transformation. The act of hearing becomes a ritual. Learning is not accumulation, but recollection—anamnesis.

Another key fragment:

Fragment B3:

“For narrow through all their limbs they see, with minds in pain. They wander, driven by folly, two-headed… they trust what is visible alone.”

This is a diagnostic of spiritual blindness—the condition of those who take the visible world as final, who cannot perceive the inner rhythm of Love and Strife shaping all appearance. The “two-headed” image is not just grotesque—it’s symbolic of the fragmented, undecided psyche. The cure is not logic, but a conversion of vision—precisely what Empedocles’ poetry aims to enact.

These fragments aren’t arguments—they are incantations, designed to awaken a memory in the soul that precedes reason. To read them as data is to miss their function. Kingsley’s insight is that Empedocles uses poetic speech as a vehicle of metamorphosis itself: each line a portal, each image a trigger, each paradox a hinge at the edge of form. Through them, the soul does not learn about transformation—it enters it.

The fragment from Empedocles—“I was once a boy, a girl, a bird, a bush, and a dumb fish in the sea”—does not simply speak of past lives; it speaks of the disintegration of fixed identity. It echoes the mystical traditions of Orphism, where the soul descends into matter, is scattered across elemental forms, and must remember itself through cycles of transformation. The dissolution of binary gender—“boy, girl”—marks the beginning of sacred remembrance. In this way, Empedocles is aligned with a vision of being that is metaxic, always between forms, never reducible to a stable identity. Kingsley, in tracking the continuity between Empedocles and Orphic thought, recognizes that such utterances are not poetic curiosities but liturgical formulae—spoken gates meant to initiate the reader into the logic of return. That he finds Orpheus atop Carl Jung’s Red Book is not surprising; both thinkers are concerned with descent into the underworld of the psyche, and with the recovery of divine speech through images, myths, and dreams.

In Paul’s epistle—“there is neither male nor female, Jew nor Greek, slave nor free”—we hear not a political slogan but an eschatological rupture. This is not the erasure of difference, but the crossing of the nodal line where difference loses its claim to ultimacy. Paul speaks, like Empedocles, from the other side of form. To say there shall be neither man nor woman is to name the moment when the soul, having passed through the elemental prisons of identity, stands bare before the divine. Here metamorphosis becomes not just ethical or cosmological—it becomes theological. Identity is not shed because it is bad, but because it is too small. It cannot carry the weight of love, or justice, or resurrection. What is born in the passage through form is not formlessness, but the fulfillment of form: the body transfigured, no longer male or female, but fire.

This passage through and beyond identity links Empedocles, Paul, and Diotima’s tale in Plato’s Symposium, where love (Eros) is revealed to be the child of Poros (resource, abundance, fullness) and Penia (poverty, lack). Diotima’s story tells us that love is not perfect unity or divine completion, but an in-between, a hunger tied to memory of the divine and the drive to return. Eros is born in a moment of sacred ambiguity—conceived not by gods in perfect form but in the friction between fullness and emptiness, wisdom and need. Kingsley’s Metis haunts this moment: not just cunning but cosmic tact, the intelligence of what weaves between. Eros is the child of this weaving. He is not purely human, nor purely divine, but always in transit. Love, like metamorphosis, is a movement of becoming that leaves no form untouched.

The figure of Medus, a rare and often overlooked name, appears near the end of the Symposium as a faint echo—possibly related to the Gorgon Medusa, but more likely playing on the word mēdōn, one who governs or arranges. Medus is the hidden masculine counterpart of Metis, a figure of order emerging from feminine intelligence. In this configuration, love itself becomes a field where polarity is not erased but dynamically held. Metis brings the flexibility, the deep cunning needed to guide souls through transformation, while Medus suggests the structure that emerges on the other side. It is no accident that Metis was swallowed by Zeus, nor that Athena—goddess of war and wisdom—is born from that digestion. The sacred tradition Kingsley excavates understands such myths not as fantasies but maps of interior transfiguration, diagrams of how the human soul is tempered, divided, and made luminous.

Together, these strands reveal a subterranean current beneath Western thought—one where logic, identity, and language are not abandoned but converted through encounter with death, dream, and divine pressure. In Empedocles, the soul becomes many to remember its oneness. In Paul, identity is crossed not to flatten the world, but to open it to eternity. In Plato’s Diotima, love is the in-between that reveals our lack and calls us upward. And in Kingsley’s vision, philosophy becomes the sacred craft it once was: not a discipline of answers, but a guided descent into the mystery, where words no longer explain but transform. This is not mysticism versus reason—it is the deeper reason we forgot when we mistook stability for truth. Metamorphosis is not a metaphor; it is how the soul moves when it remembers it was never meant to stay still.

The word metaxic comes from the Greek metaxu (μεταξύ), meaning “between” or “in the middle.” It appears most explicitly in Plato’s Symposium, where Diotima describes Eros as a daimon—a being that lives metaxu gods and humans. He is neither fully immortal nor fully mortal, neither fully wise nor completely ignorant, but always reaching, desiring, becoming. To be metaxic, then, is to dwell in the in-between—not as a failure to reach a goal, but as a fundamental mode of being. Eros is metaxic because love is not possession, but longing. It holds us suspended between what we are and what we are becoming.

To call something metaxic is to say it resists closure. It neither collapses into one pole nor escapes into the other—it sustains the tension. In this sense, the soul in Empedocles is metaxic: it moves between elemental forms, between divine memory and bodily exile. Paul’s new creation is metaxic: it abolishes old divisions not by negating them, but by passing through them into something beyond their logic. Even metamorphosis itself is metaxic, because it names not a state but a passage—a shape that is held just long enough to yield to another. The Mass-Omicron model is built on this tension: Ω seeks form, o undoes it, but the truth is always in the metaxic dance between them, where the system is most alive.

The elemental, for Levinas, precedes any structured world or objectivity. It cannot be possessed or grasped. It is anterior to cognition and transcendent in its immanence. To be steeped in the elements is to enjoy a world that is not yet totalized — a kind of pre-ethical luxury, or felicity, that does not yet confront the Other or responsibility. This enjoyment is material but not utilitarian — it is dwelling in warmth, in nourishment, in repose. The elements thus constitute the first site of subjective satisfaction, not through mastery but through a kind of passive reception, even absorption.

This is a subtle but profound dimension of Levinas’s early thought, particularly in Totality and Infinity, where he treats the elemental—earth, air, warmth, light, nourishment—not as objects of knowledge or possession, but as the preconditions of dwelling. The elemental precedes the world as structured or intelligible. It is not in the world; it is what gives rise to the world as a site of habitation. In this sense, the elemental is anterior to intentionality—it is not what we face, but what we are immersed in. To be steeped in the elemental is not to stand over it, nor to interpret it, but to enjoy it in a mode of passive absorption that Levinas calls enjoyment (jouissance). This is not hedonism, nor instrumental use—it is the self in repose, at home with being, not yet summoned to respond.

What makes Levinas’s treatment unique is his refusal to reduce this enjoyment to cognition or even to morality. Before the ethical demand of the Other—before responsibility, asymmetry, or even dialogue—there is this primordial satisfaction, a kind of pre-ethical luxury that allows the self to emerge as a center of lived meaning. The elements nourish without asking, they warm without commanding, they offer sustenance without confrontation. This is not utility—it is felicity, a joy in existence that is not grounded in domination. In fact, Levinas insists that the elemental cannot be mastered or truly possessed. It resists totalization not through power, but through transcendent immanence—it is fully given, yet always escaping the form of a concept or a tool. Thus, in Levinas, the elemental is the ground of sensibility, the condition for interiority, and the silent background against which ethics can later emerge. But it is never reducible to ethics itself—it is the warmth in which a self first learns to dwell, before it learns to answer.

Ambient o is the field of immanence before demand, before form, before encounter. It is the atmosphere of possibility that surrounds and saturates the subject without confronting it. Like Levinas’s elemental, ambient o cannot be grasped or mastered—it is not a thing among things, but a condition of openness, an aural background that resists objectification. It nourishes without naming, seduces without summons, and allows the self to unfold in the warmth of being without responsibility. If Ω is form, structure, or response—ambient o is what lets form arise by not yet insisting. It is divergence before rupture, possibility before decision, becoming before act.

In this way, ambient o can be understood as diffuse grace, the silent surplus of the real that surrounds the emergence of the subject. It is the murmur of the world that is not yet world; the fullness that is not yet structured; the joy that is not yet tested. Like the elemental, ambient o gives without taking. It is not the chaos that threatens coherence, but the gentle sea from which coherence emerges. It is the passive condition for creation, the metaxic breath in which Mass (Ω) will one day speak—but has not yet been called. To dwell in ambient o is not to evade ethics, but to exist in the time before responsibility, in the glow of an unstructured welcome, where the soul feels without knowing, receives without cost, and rests without justification.

Orpheus is the poet of ambient o—the singer who does not command but summons, who does not grasp the world but causes it to sway. His lyre does not impose form but coaxes it from silence. Like Empedocles, Orpheus moves through the elemental, not above it: trees lean toward him, stones weep, animals gather—not through power, but through resonance. He is not master of nature but its interlocutor. And yet, he too is metaxic: born of Apollo and the Muse, child of light and song, he dwells between the mortal and the divine. His descent into Hades is not heroic conquest but intimate refusal of separation—he goes to retrieve not a prize, but a beloved. He moves through death with music as his only shield, and this gesture—the turning toward Eurydice with love stronger than law—becomes the axis of his ruin and his revelation.

In the myth, the rule is clear: do not look back. But Orpheus does, and that backward glance becomes the turning point—the nodal line. It is the moment where Mass seeks to hold what o refuses to fix, where form tries to capture presence, and the result is loss. Eurydice vanishes again, not because Orpheus fails, but because love, in its deepest mode, cannot possess what it adores. The backward glance is not disobedience—it is despair in the face of absence, or perhaps the final proof that beauty belongs to the threshold. Orpheus, like Empedocles, is torn across lives. He becomes not just a mythic poet, but a symbol of what it means to speak from within transformation—to utter songs that move the world, even as they cannot hold it still.

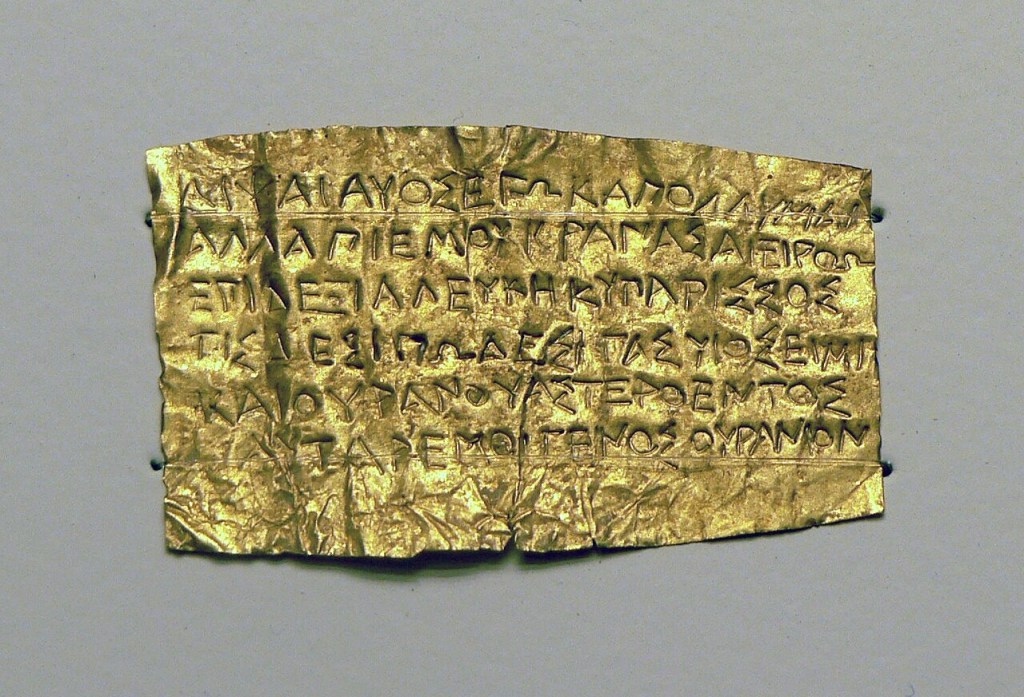

Peter Kingsley sees in Orpheus what he sees in Empedocles: not a storyteller, but an initiate. The Orphic tradition, with its emphasis on purification, reincarnation, and cosmic descent, is not myth as fiction but myth as procedure. The verses of Orpheus were not simply meant to entertain—they were designed to guide the soul. The golden tablets found in Orphic graves—inscribed with instructions for the dead—speak directly to the journey through the underworld, offering passwords, reminders, and affirmations of the soul’s divine origin and return. Here again is ambient o: the surrounding memory of divinity, before it crystallizes into name or identity. Orpheus sings so that something ancient in us might stir, recall its shape, and begin to rise.

Orphic metamorphosis is not about changing into something else—it is about recovering what was always there, beneath the layers of forgetting. The soul is not made, it is unveiled. The Orphic initiate learns to see life as a preparation for death, and death not as an end, but as a return. The Orphic body is temporary, porous, and permeated by sound; it is a vessel tuned by the cosmos, broken and repaired through longing. In this light, the myth of Orpheus is not tragic—it is alchemical. The descent fails only if we measure it by retrieval. Measured by revelation, by the awakening of song that can no longer be silenced, it succeeds.

In Orpheus, as in ambient o, there is no final arrival—only resonance, recurrence, and the slow unfolding of form from the depths of formlessness. His myth is the reminder that the most powerful transformation does not impose shape, but listens. It does not seize, but sings. And it is precisely this music—this trembling between what is and what is no longer—that teaches us how to dwell, to grieve, and to begin again.

The Totenpass—literally “passport of the dead”—refers to the thin gold tablets placed in the graves of Orphic and Pythagorean initiates, inscribed with instructions for navigating the afterlife. These were not symbols, not metaphors, but ritual instruments—maps meant to be read by the soul as it crossed into the underworld. The soul, upon arriving in Hades, would be met with choices, questions, and temptations, and the Totenpass provided the precise words to speak, the right turns to make, the signs to follow. “I am a child of Earth and starry Heaven,” one tablet proclaims, “but my race is of Heaven alone.” These lines are not mythopoetic flourishes—they are utterances of identity, spoken not for remembrance but for return.

The Totenpass reveals that Orphic wisdom is not passive cosmology but technē psychēs, a sacred craft of the soul. The soul, fragmented by incarnation, must remember itself amidst the dissolution of bodily form. What Empedocles describes in his elemental cycles—passing through boy, girl, fish, bird—is given structure here: a teleology, a path. The golden tablet is not an abstract theology but a mnemonic device, a resonant imprint of belonging. Its function is to rekindle the soul’s divine memory within the disorienting terrain of death, when all else has been stripped away. It is the crystallized form of ambient o, carried across the boundary, shaped into speech, and activated in the liminal space between forgetting and return.

The ethics embedded in the Totenpass are subtle but absolute. The soul must not drink from the river of Lethe—the water of forgetting—but from the waters of Mnemosyne, memory. This choice is not just about recollection; it is about fidelity to one’s divine origin. In this framework, death is not a judgment in the juridical sense, but a test of attunement: has the soul remembered what it is? Has it passed through form without becoming trapped in it? This aligns deeply with the Mass-Omicron vision: Ω without o forgets its origin and collapses into rigid form; o without Ω drifts endlessly. But the soul that can carry its o—its divergence, its longing—within a coherent Ω-form, even into death, is the soul that is ready to return.

The Totenpass, then, is an artifact of a forgotten metaphysics—one that understands that language is not just communication, but threshold navigation. The tablet’s lines are not beliefs but keys, each syllable tuned to open specific gates within the self and within the underworld. They are a form of operative poetry, functioning at once as cosmology, ethics, and ontological orientation. Orpheus, who gave voice to the underworld and whose song reached where logic failed, is the mythic origin of this wisdom. Kingsley’s reading of Empedocles aligns here perfectly: the philosopher is not an observer of change but a guide through it, and the fragments he leaves behind are not theories—they are reminders placed along the path, golden instructions for a soul that must pass through fire and darkness with nothing but memory and voice.

The Totenpass is thus the inverse of forgetting: it is form held close enough to survive the formless. It is Ω written in gold, cradling o within it. Not a system of control, but a slender strand of orientation. And perhaps that is what sacred philosophy has always been—not knowledge for knowledge’s sake, but guidance for a soul suspended between the stars and the dirt, trying to find its way home.

Field writing emerges where thought and matter, experience and myth, no longer belong to separate registers. It is writing that listens to the conditions of emergence—writing from within, not about, the field. Like the Orphic Totenpass or Empedocles’ fragments, field writing is not analytic but operative; it aims not to explain, but to transform, not to master, but to move with. It is writing that carries the trace of the ambient o, writing steeped in the elements—dust, light, decay, voices overheard and half-remembered, thresholds crossed in silence. It dwells in the metaxic: between vision and record, between ritual and trace, between event and memory.

To write in the field is not merely to observe phenomena—it is to enter into their rhythm, to let the field write back. It is attunement rather than representation. What the Totenpass does for the soul, field writing does for experience: it guides, reminds, unlocks. It is writing that knows it is being carried, not simply composed. It refuses to separate form from world, body from site, voice from wind. Like the incantatory verses of Empedocles or the backwards glance of orpheus, field writing is never quite stable—it shimmers, it risks, it listens more than it speaks. It is Ω inscribed in trembling lines, with o pressing gently beneath the surface, shaping what must be remembered.