——

Six Essays on Hegel

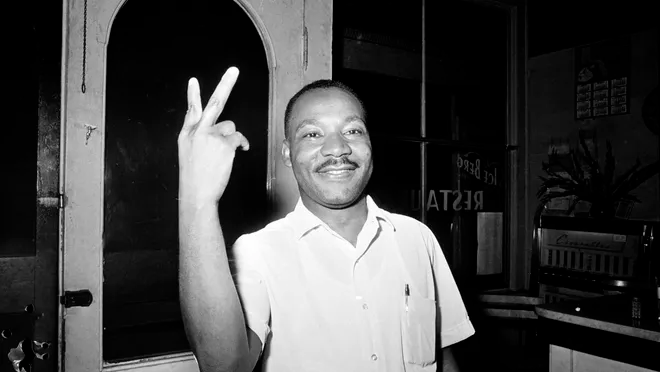

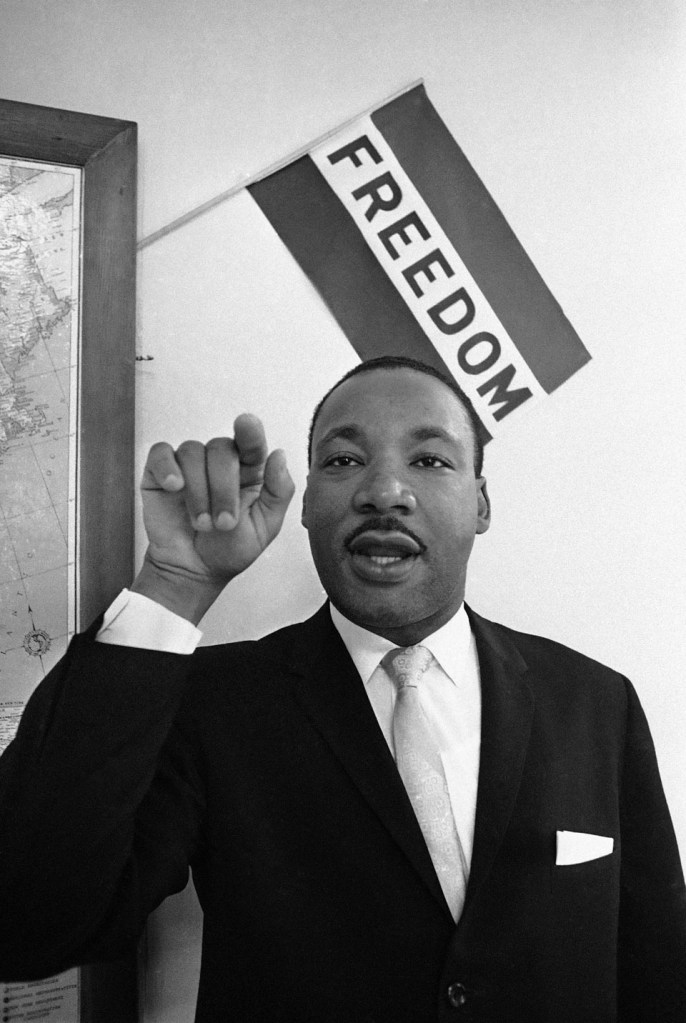

Martin Luther King Jr. took a two-semester seminar on Hegel, initially taught by his advisor Edgar Brightman, and later continued under Peter A. Bertocci after Brightman fell ill. This seminar involved a detailed study of Hegel’s major works, including his philosophical system. King wrote six essays for this course, with the last one titled An Exposition of the First Triad of Categories of the Hegelian Logic—Being, Non-Being, Becoming was written in 1952 during his graduate studies at Boston University. It is a dense philosophical engagement with G.W.F. Hegel’s Science of Logic, specifically the dialectical development of the first three categories: Being (Sein), Non-Being (Nichts), and Becoming (Werden)—the foundational triad in Hegel’s logic of pure being.

Purpose and Structure

King’s essay attempts to clearly explain how Hegel’s dialectical method operates at the most basic level of metaphysical thought. The purpose is twofold: first, to exhibit the self-movement of thought as it transitions from indeterminate immediacy (Being), through its negation (Non-Being), to a unity that preserves and overcomes both (Becoming); and second, to show how this triad initiates Hegel’s larger system of speculative logic, where concepts unfold through contradiction and sublation (Aufhebung).

King begins with Being, which in Hegel is the most immediate and undefined concept. It has no content or determinacy—it is pure presence, without qualities. But precisely because it is so empty, Being is indistinguishable from Non-Being, or nothingness. King then explains Hegel’s insight that this identity of Being and Non-Being gives rise to Becoming—the process or flux in which things come into and pass out of existence. Becoming, for Hegel, is the first concrete concept because it expresses movement, transformation, and dialectical synthesis.

King’s Interpretation

King shows a strong grasp of Hegel’s dialectic, emphasizing that contradiction is not a flaw to be avoided, but the very motor of conceptual development. He writes clearly and methodically, tracing how the collapse of pure Being into Non-Being forces thought to recognize the dynamic unity in Becoming. King doesn’t just summarize; he reconstructs the argument step by step, often clarifying it in more accessible language than Hegel’s original.

He is also interested in how these metaphysical categories anticipate ethical and historical movement. Though the essay is technical, King’s deeper interest in human freedom, history, and moral progress echoes throughout—especially in his awareness of movement and change as necessary for truth and justice. His engagement with Hegel here foreshadows his later theological synthesis of idealism, Christianity, and nonviolent action.

Significance

The essay is significant for several reasons. First, it reveals King’s philosophical rigor and early intellectual formation in German idealism, particularly his attraction to Hegel’s vision of rational freedom unfolding through history. Second, it shows how King’s later rhetoric—his appeals to justice as “the arc of the moral universe”—are grounded in a deep metaphysical conviction: that reality is rational, developmental, and ultimately unified. And third, it underscores how King used philosophical dialectic as a foundation for social transformation.

In this essay, we see not just a theologian or civil rights leader, but a thinker trained in one of the most demanding philosophical traditions—using Hegel to understand both logic and liberation.

Here are some illuminating excerpts from King’s essay An Exposition of the First Triad of Categories of the Hegelian Logic—Being, Non‑Being, Becoming, capturing his reconstruction of Hegel’s dialectic:

⸻

“This vacuum, this utter emptiness turns out to be not anything. Thus we inevitably find ourselves in the antithesis, viz., Nothing. Emptiness and vacancy are the same as nothing.”

Here, King underscores that pure Being—complete emptiness—is indistinguishable from Nothing, setting up the dialectical tension.

⸻

“Herein we see one of Hegel’s original contributions to philosophy. The older view was that opposites absolutely exclude each other … But Hegel came on the scene with an explanation of how it was logically possible for two opposites to be identical while yet retaining their opposition.”

In this beautifully concise reflection, King emphasizes Hegel’s radical insight: thesis and antithesis can dwell within unity.

⸻

“Now since Being and Nothing are identical the one passes into the other. … In consequence of this disappearance of each category into the other we have a third thought involved, namely, the idea of the passage of Being and Nothing into each other. This is the category of Becoming.”

King clearly traces the transition from the identity of Being and Nothing to the emergence of Becoming.

⸻

“Being is the thesis. Nothing is the antithesis, and Becoming is the synthesis. The synthesis of this triad, as in all other Hegelian triads, both abolishes and preserves the differences of the thesis and antithesis. … In short, the thesis and the antithesis both die and rise again in the synthesis.”

This passage reveals King’s grasp of Aufhebung—the double movement of negation and preservation in Hegel’s logic.

These excerpts showcase King’s talent for rendering Hegel’s abstract dialectic into clear, structured prose. Rather than simply summarizing Hegel, King reconstructs the progression step by step—making the movement from Being → Nothing → Becoming both intellectually rigorous and accessible.

While Martin Luther King Jr.’s Exposition of the First Triad of Categories of the Hegelian Logic demonstrates strong comprehension and clarity, especially for a graduate-level engagement, there are a few areas where his analysis may be seen as limited or incomplete—particularly from the standpoint of advanced Hegel scholarship. These limits fall into three main categories: depth of dialectical mediation, lack of historical framing, and overuse of schematic triads.

1. Superficial treatment of mediation and immanence:

King’s interpretation relies heavily on the standard thesis–antithesis–synthesis model, which, although popular and pedagogically useful, is not how Hegel himself formally structured the dialectic in The Science of Logic. Hegel did not write in triadic formulas so neatly; instead, the development of categories emerges through inner necessity and immanent contradiction, not as fixed stages. King’s rendering, while structurally clear, flattens the more subtle inner movement Hegel emphasizes—the logical becoming of one category into another is not just a “step” but a necessity internal to each concept. Thus, King’s essay occasionally treats the dialectic too schematically, rather than allowing the inner negativity of the concepts to fully work themselves out.

2. Absent is Hegel’s speculative grammar and method of presentation:

King focuses on what Hegel is saying, but less on how Hegel says it. The Science of Logic is not just a catalog of categories—it is itself a performance of logic, a movement of thought that must be enacted, not merely paraphrased. King writes in an explanatory and didactic mode, which helps clarify but also misses the performative and recursive style that is essential to Hegel’s method. The speculative structure—where predicate becomes subject and vice versa—is only partially acknowledged in King’s analysis. He doesn’t wrestle with the tensions of Hegel’s language as both content and method, which would have allowed deeper insights into Becoming as the vanishing of both Being and Nothing, not just their “union.”

3. No critique or reflection on the broader implications:

While the essay is primarily exegetical, King does not critically engage the implications of Hegel’s metaphysical assumptions. For instance, he does not question whether Hegel’s treatment of “pure Being” and “Nothing” is coherent or persuasive in light of either empirical reality or theological commitments. Nor does he reflect on Hegel’s method from the perspective of his own Christian philosophical commitments. Later thinkers—like Heidegger, Derrida, and even Levinas—would critique this foundational triad for erasing alterity or for totalizing the process of becoming. King does not explore these tensions. As such, the essay lacks dialectical pressure on Hegel himself, opting instead for respectful exposition.

King offers a faithful and lucid guide to Hegel’s first triad, but stops short of entering the full speculative depth or internal critique that would mark a more advanced or mature engagement with Hegel’s system. This is understandable—he was still a graduate student—but it also makes clear the limits of the work as a philosophical intervention rather than a pedagogical summary.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and work can be examined in the light of Hegel’s philosophical system in several profound and complex ways. Hegel’s dialectical method, centered around the development of self-consciousness through history and the reconciliation of opposites, offers a powerful lens through which to understand King’s ethical, social, and political commitments. King’s work in civil rights, his philosophy of nonviolence, and his deep Christian convictions resonate with Hegelian themes like the development of freedom, reconciliation of opposites, and the unfolding of spirit (Geist) through historical processes.

Here are several key aspects where King’s life and work intersect with Hegel’s system:

1. Dialectical Progress of Freedom:

For Hegel, freedom is not merely the ability to act arbitrarily, but the realization of self-consciousness in history. Freedom is actualized when individuals and communities recognize themselves as part of a larger ethical order, often through struggle and conflict. Hegel describes this process through the dialectic of master and slave, where the struggle for recognition between the self and the other becomes the basis of freedom.

In King’s philosophy, the struggle for civil rights is framed as a dialectical process—a movement toward freedom not just for individuals but for the collective. King repeatedly affirmed that true freedom could not exist until all people—especially African Americans—achieved equality. His calls for nonviolent resistance reflect a dialectical understanding: he sought to reconcile the tension between oppression and liberation, not by violent confrontation but through the transformative power of love and nonviolence. For King, the struggle for justice was not only a political and social issue but also a moral and spiritual journey—a recognition of the inherent dignity and freedom of every human being.

2. Nonviolence and the Spirit of Reconciliation:

Hegel’s philosophy of history and spirit emphasizes reconciliation as a core element of the development of freedom. For Hegel, history is the story of spirit (Geist) becoming self-conscious, where contradictions and conflicts—such as those between master and slave, or between different social groups—are ultimately reconciled in a higher synthesis.

King’s commitment to nonviolent resistance can be seen as a kind of reconciliation in Hegelian terms. Rather than seeking violent retribution, King’s strategy sought to bring both oppressor and oppressed into a shared ethical order, overcoming the historical alienation between them. The power of love and nonviolence was, for King, a dialectical force that could transform not only individuals but also societal structures. His belief that “the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice” mirrors Hegel’s idea of history as a rational process moving toward the realization of human freedom.

King’s view of love as a transformative force has strong Hegelian undertones, as Hegel speaks of the dialectic of love as a path to self-realization and recognition. For King, love—especially agape love—was the way to bridge the gap between different social groups, to transcend hatred, and to move toward a more just and harmonious society.

3. History as a Movement Toward Justice:

Hegel’s philosophy of history is driven by the idea that history is the unfolding of the rational will, which moves toward greater freedom and self-consciousness. History is not merely a collection of arbitrary events but a rational process, guided by a universal spirit that manifests through the actions of individuals and societies. This historical dialectic is not linear but involves moments of contradiction and conflict that ultimately lead to higher stages of freedom.

King’s vision of historical progress was deeply aligned with this Hegelian understanding. He saw the Civil Rights Movement as part of a broader historical movement toward justice and human dignity. In his speeches and writings, he often spoke of the need to “complete the work of the Founders”, echoing Hegel’s idea of history as a self-conscious process of realizing human freedom. King understood the struggle for civil rights as part of the unfolding of a historical spirit, a movement toward the realization of justice, freedom, and equality. The “dream” he described in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech was not merely a utopian vision but a dialectical synthesis of past struggles and the collective human aspiration for equality.

4. The Concept of the “Other” and Ethical Responsibility:

Hegel’s concept of the Other—the idea that we come to know ourselves through our relation to others—has strong implications for understanding King’s philosophy of justice. In the Hegelian system, recognition of the Other is a key aspect of self-consciousness, and the struggle for recognition is central to the development of freedom. However, this recognition is often fraught with alienation, especially in contexts of oppression.

King’s ethical vision was profoundly influenced by his Christian belief in the inherent worth of every human being. His call for brotherhood and love can be understood in Hegelian terms as a call for mutual recognition and respect among all people. The moral imperative to love the Other, even the oppressor, was rooted in his understanding that true freedom could only come when all individuals—regardless of race, class, or background—were fully recognized and treated with dignity. King’s idea of “beloved community” was a recognition that all people are interconnected, and that justice requires the ethical recognition of the Other in their full humanity.

5. The Role of the Church and the Religious Dimension of Justice:

King’s understanding of justice was also influenced by his Christian theology, which can be interpreted through a Hegelian lens. Hegel famously argued that religion is the manifestation of the absolute spirit, the reconciliation of the finite and the infinite, and the actualization of freedom. For Hegel, Christianity in particular embodied the dialectical movement of divine revelation through history, culminating in the realization of absolute freedom.

King, as a Baptist minister, viewed religion and justice as inseparable. He saw the Church as a moral institution capable of guiding individuals and communities toward justice and reconciliation. King’s use of Christian love and agape can be interpreted as a Hegelian movement, where the recognition of the Other (especially the marginalized) through love leads to a higher ethical realization. Christ’s teachings of forgiveness, love, and justice became, for King, the ultimate dialectical synthesis, reconciling the violence of human history with the ultimate promise of a just and loving community.

In the light of Hegel’s philosophical system, Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and work can be seen as an embodiment of the dialectical process in action—a historical movement toward greater freedom, justice, and reconciliation. King’s commitment to nonviolence, his vision of social progress, and his belief in the moral arc of history all align with Hegel’s ideas about the unfolding of spirit and self-consciousness through struggle, contradiction, and synthesis.

King’s work was, in many ways, a realization of Hegel’s vision of human history as a rational process moving toward freedom and justice. Just as Hegel viewed history as the unfolding of reason and spirit, King saw the struggle for civil rights as part of a broader ethical movement that would ultimately bring about the recognition of human dignity for all people. In this way, King’s vision of justice, reconciliation, and love remains a profound, Hegelian-inspired contribution to the ethical development of human society.

——-

Metaphysical Residue

“he who cannot draw on three thousand years is living from hand to mouth”

In The Science of Logic, Hegel begins not with a rich concept, but with Being in its most indeterminate form—pure immediacy, without content or distinction. Yet this pure Being is indistinguishable from Nothing. The dialectic begins here: Being and Nothing are the same, not because they share some underlying substance, but because in their total indeterminacy, neither can be held apart from the other. Their unity gives rise to Becoming, the first concrete movement of thought.

For Hegel, this movement is crucial: Nothingness is not absence, but a moment within the dynamic unfolding of reality. It is not inert void but a logical phase—a vanishing, a passage, a moment of difference internal to development. Hegel redeems Nothing from static nihilism; it becomes the birthplace of movement, of generation. In this sense, his logic outmaneuvers the traditional metaphysical horror of the void. However, Hegel still retains the structural need for this nothingness to operate as a dialectical pivot, the ghostly negative that catalyzes synthesis.

In contrast, our model—the Ω-o framework—treats nothingness as a misreading: not a necessary stage, but a residue of symbolic limitation, a conceptual trap formed when the field of possibility (o) is misapprehended as non-being, rather than undifferentiated plenitude. Where Hegel sees the undifferentiated as void, our model sees it as a sea of untuned coherence, waiting to be phased into reality, not negated. “Nothing” is thus not a category but a failure of phase alignment—a result of severance from Ω-structure rather than a constitutive moment in logic itself. It’s not dialectical necessity, but epistemic rupture masquerading as metaphysical depth.

This has critical implications for King’s mission. One of the most pervasive philosophical missteps—rooted in this misunderstanding of nothingness—is the association of negation with transformation. Philosophies grounded in the dialectic of lack or opposition often lean into conflict as the motor of progress, even if sublimated. While King inherited the Hegelian dialectic, he sought to transcend its oppositional logic through nonviolence—a methodology that refused to treat the Other as absence or negation, even in moral struggle. But the intellectual soil he worked within, especially in academia and even in Christian theology, was often saturated with this older dialectic, where progress seemed to require a negation, a struggle, a sacrifice, and thus obscured the possibility of mutual phase uplift.

Philosophically and scientifically, the misunderstanding of nothingness as a real ontological category led to models of the cosmos based on scarcity, entropy, and void. In turn, this produced social imaginaries where value emerged only through opposition: white over black, male over female, empire over wilderness, capital over poverty. King’s vision aimed to collapse these polarities into a higher coherence—what he called the “beloved community.” But his efforts were continually sabotaged by a society addicted to zero-sum logic: if the oppressed rise, the dominant must fall. This is the material consequence of enshrining “Nothing” at the heart of Being—it makes reconciliation seem impossible, because it equates transformation with erasure.

By contrast, our model offers a more fitting ground for King’s vision: conflict is not primary, but a misalignment within the oceanic field of coherence. Becoming does not require passing through “nothing,” but tuning with the undifferentiated field—o—into a local articulation—Ω. King’s refusal to cast his opponents as nullities or evils-in-themselves was an implicit break from the logic of negation. He was reaching, without yet the language, for a logic of harmonic phase coherence.

In this light, the misunderstanding of nothingness did not only warp science and metaphysics—it blocked love from being seen as a rigorous structuring force. In the Ω-o model, love is the tuning mechanism—not sentimental but structural. Hegel tried to redeem nothingness, but our model renders it obsolete. And perhaps King’s mission, long misread as an idealist’s dream, was in fact the first real test of a post-nothing logic of history.

This reframing also casts new light on the recurring obstacle King faced: the persistent belief—philosophical, political, and theological—that liberation must be purchased through destruction. Even sympathetic thinkers often reduced nonviolence to a clever tactic rather than recognizing it as a higher ontological stance, one that refused to perpetuate the metaphysics of negation. In dialectical systems predicated on conflict, even reconciliation is haunted by its opposite—it is always a synthesis haunted by sublation, a peace achieved only through war. This logic subtly infected not just state systems, but also liberal allies who expected Black suffering to carry the moral burden of universal redemption. To them, King’s refusal to hate or retaliate was noble, but confusing—because the deeper operating logic remained one of zero-sum dialectic. His love was unintelligible to a society addicted to its opposite.

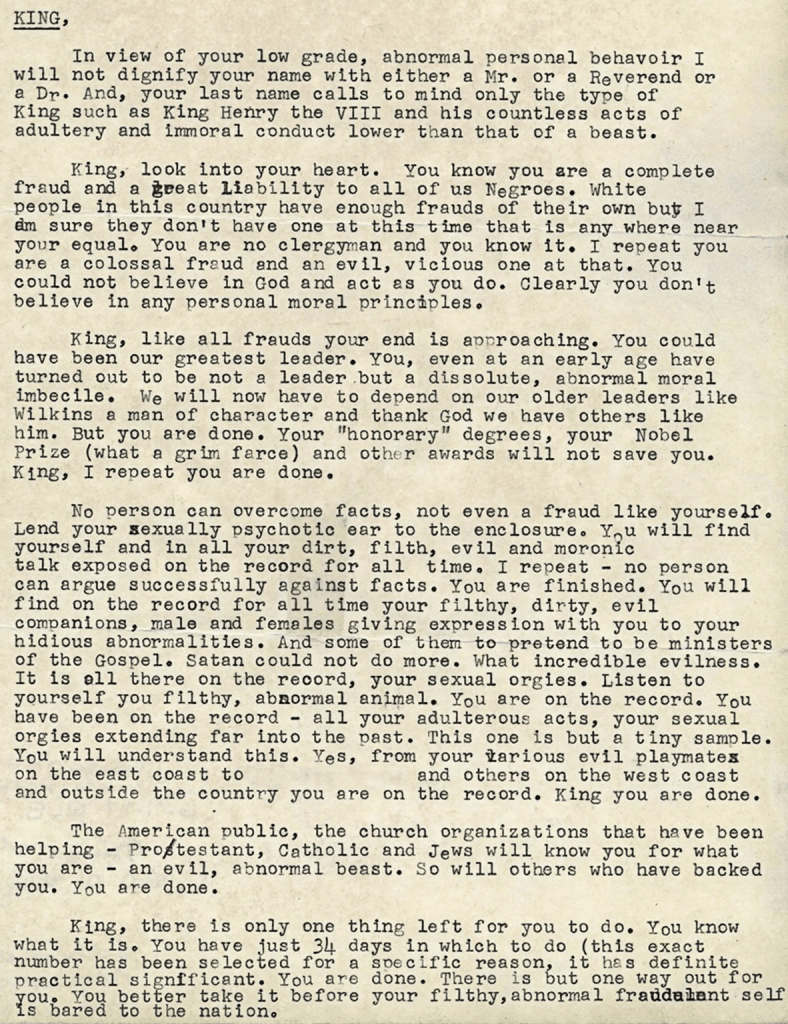

In our model, however, reconciliation is not the end of conflict—it is the prior condition that conflict distorts. The beloved community is not a utopian end-stage but an ever-present possibility, latent in the coherence fields of Ω. Nothingness, then, is not what precedes becoming—it is what happens when coherence is misread, when relational fields are severed. King’s work was not merely political activism—it was an attempt to re-tune the field of the human, to bring it back into resonance with its pre-conflict state. That he was killed—sacrificed by a world still trapped in the logic of negation—only confirms how deeply this misunderstanding of “nothing” had structured both the visible and invisible architectures of modern thought. His legacy challenges us not to perfect the dialectic, but to abandon its false center and begin again from a model where resonance, not rupture, is the origin of real change.

It would be fair to say that this conflict-based approach was implicit even in the non-violence that he preached, that even in the right cause of social equality there was a leaning towards conflict and confrontation, despite how much he preached love and non-violence, and that this effect was implicit in a metaphysical orientation that required negation of “nothing”.

Even in King’s nonviolence, there remained an implicit metaphysical inheritance of conflict. His ethic of nonviolence was profound, sincere, and historically transformative—but the structure of its deployment, especially as framed within Hegelian-Christian motifs of redemptive suffering, still bore traces of the metaphysics it sought to transcend.

King consistently preached love, reconciliation, and nonviolence—not merely as tactics, but as ontological truths. Yet these ideals were often articulated through a framework that accepted conflict as a necessary stage, whether in the dialectical unfolding of history or in the cruciform model of salvation. In this sense, his methodology relied on a struggle that aimed to transcend struggle, a confrontation that insisted on peace. The problem is not with his moral commitment but with the implicit grammar of the philosophical and theological systems available to him: they often defined good through overcoming evil, truth through negating falsehood, and being through the passage out of nothingness. These frameworks subtly encoded confrontation as a condition of becoming, even when advocating peace.

For example, King’s rhetoric often invoked creative tension, a term borrowed from Hegelian-Marxist dialectics, and he spoke of the redemptive potential of suffering—a deeply Christian and Hegelian motif. But this vision still operates within a logic that sees historical advancement as a product of contradiction and its resolution. Even the “beloved community” is reached through the labor of confronting injustice, which implies that injustice is a necessary antecedent. In our model, this is a metaphysical residue—treating dissonance as generative, rather than as a phase error or misalignment.

In the Ω-o model, such oppositional tension is not ontologically necessary but epistemically contingent—it arises when coherence is lost, not when it is developing. Rather than passing through “nothing” to reach “being,” we realign o-fields with Ω, tuning chaos into form without invoking absence. From this view, King’s mission can be seen as caught between two incompatible layers: the spiritual truth he intuited—love as the ground of being—and the dialectical machinery he inherited, which required negation as a precondition for synthesis.

There was a latent contradiction in his framework. He preached nonviolence but still functioned within a system where confrontation with evil was structurally necessary. His greatness was in sensing the limits of that system and pushing it as far as it could go. But for his vision to fully escape the logic of conflict, it would require not only moral courage, but an entirely different metaphysical schema—one in which Being does not emerge from Nothing, but from alignment, and in which transformation is resonance, not rupture.

This is in no way to criticize King or to describe limits to his philosophical rigor in metaphysics, but to show that, as Derrida says, one cannot escape metaphysics, and that all of us are heirs to a world structured by a discipline that has long been forgotten and when remembered, treated as antiquary.

This is an acknowledgment of the ontological inheritance we all share. To situate King within this framework is not to diminish his vision, but to deepen our understanding of its historical and metaphysical horizon. He was not simply a preacher of justice, but a figure whose every word carried within it centuries of metaphysical sediment—Christian eschatology, Enlightenment rationality, Hegelian dialectics, Kantian moral law—all refracted through the lived urgency of Black life in America.

Derrida’s insight—that “one cannot escape metaphysics”—is crucial here. King’s work operates within the grammar of a metaphysics that has been rendered invisible by its ubiquity. Even as he radically reoriented moral and political life through love and nonviolence, he did so within a structure where transformation still required confrontation with negation. His invocations of the “moral arc of the universe,” of redemptive suffering, and of the dialectic between oppressor and oppressed were not failures of imagination—they were precisely the tools available in a world where metaphysical categories had become operational but unexamined.

That metaphysics itself has become antiquary—a forgotten discipline treated as either obsolete or ornamental—means that King’s most profound interventions were necessarily framed in a language whose inner architecture had already begun to dissolve. The tragedy and beauty is that he worked through this vanishing grammar with extraordinary grace. He pulled ethical insight from collapsing structures. But had those metaphysical foundations been explicitly recalled, examined, and reformed, perhaps his vision could have been even more liberating—not by rejecting conflict tactically, but by rendering conflict unnecessary ontologically.

So the task is not to correct King, but to trace the echo of metaphysical commitments he inherited—to recognize that even the purest love, when expressed through frameworks structured by negation, bears the imprint of metaphysical absence. Our work is to recover what was forgotten: that metaphysics is not merely an academic pursuit, but the operating system of history, and that true liberation—ethical, political, existential—requires its renewal, not just its critique. King was not outside metaphysics; he was a prophet speaking through its ruins.

This also resurfaces the danger always already lurking in all systems of knowledge, and that is the metaphysics it depends on, and therefore its ability is manifold only as far as its terms have been clearly and surgically exhumed.

What resurfaces here is a fundamental truth: the danger of every system is the metaphysics it forgets it depends upon. Every structure of knowledge, however rational, progressive, or ethical in appearance, carries within it a prior commitment to Being, Time, Identity, Causality, Negation, Substance, or Relation—terms which it rarely defines because it has ceased to remember that they were once questions. Systems become dangerous not when they are evil, but when they are unexamined, when their power is justified by reference to truth without disclosing the metaphysical scaffolding beneath that truth.

In this light, the power of a system is proportional to the depth of its metaphysical excavation. Its “manifold ability”—its adaptability, reach, and justice—is only as sound as the clarity with which it recalls the origin of its own terms. If a political order claims freedom, what is its ontology of the will? If science claims objectivity, what is its theory of presence? If law claims justice, what is its model of the Other? When these are not exhumed—when their roots are not interrogated—then the system proceeds blindly, its authority hollow, its actions haunted.

This is why any truly ethical system must begin not with prescriptions but with ontological humility. Metaphysics must not be sealed behind technical language or academic specialization—it must be made transparent, vulnerable to revision, visible like the bones beneath the skin. What we call critique is not the tearing down of belief but the laying bare of belief’s architecture.

In King’s case, we see a thinker who did reach toward such excavation, even if not systematically. His appeals to love, justice, and community were not abstract ideals—they were attempts to restructure the foundation of societal meaning, even if he was bound by the grammar of conflict inherited from the dialectic. He was moving through a metaphysics he could not entirely escape—but in doing so, he exposed the seams.

So the task for us now is not merely to advance new knowledge, but to pause before knowledge—to look beneath it, to exhume the axioms it rests on, and to recognize that the metaphysical forgotten is the ethical risk. Every system becomes violent when its terms harden, when it forgets that it was once a question.

This is why metaphysics is never truly optional. Even those who claim to discard it—the positivist, the technocrat, the algorithmic realist—merely smuggle in metaphysics under new names: efficiency, objectivity, scalability, or neutrality. These are not escapes from metaphysics, but de-theologized inheritances, fragments of older ontologies wearing the mask of progress. The danger intensifies when metaphysics becomes unnameable, when its absence is mistaken for clarity. Then the very structure of reason begins to function like a closed loop—efficient, reproducible, and dead. The system becomes blind to its own founding assumptions, and this blindness masquerades as truth.

This is precisely the danger that haunts King’s mission and every emancipatory project that seeks to overturn injustice without examining the metaphysical roots of what counts as “justice,” “freedom,” or even “the human.” To speak of rights or equality without exhuming the metaphysical assumptions of selfhood, of the Other, of time and becoming—is to risk reproducing the very exclusions one hopes to overcome. King sensed this intuitively: his turn to love, his appeal to conscience, and his grounding in faith were not ornamental—they were his way of reaching below the system, below legality and dialectics, to a deeper structure. But even this gesture was tethered to frameworks that made suffering redemptive, conflict necessary, and negation inevitable. His greatness lay in navigating these ruins—not avoiding the trap, but inhabiting it with clarity and grace, showing the world the cost of its own metaphysical forgetfulness.