“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”

“He was thinking about something, and stood there trying to get clear on it. And when he didn’t succeed, he still stood there, trying. It was already noon, and people were noticing and saying in amazement, ‘Socrates has been standing there thinking ever since dawn!’ Finally, in the evening, some Ionians brought out their bedding after dinner — it was summer — to sleep in the open air, to see if Socrates would stand there all night. And sure enough, he stood until morning. And at dawn he offered a prayer to the sun and went away.”

—-

Book I of The Republic, Socrates disarms Thrasymachus’s bold claim that “justice is nothing but the advantage of the stronger.” Thrasymachus has argued that rulers craft laws in their own interest and call that justice, so justice is just obedience to the will of the powerful. But Socrates gradually peels this claim apart—not with brute refutation, but with surgical irony and dialectical patience. After some initial exchanges about the nature of ruling and error (whether rulers can make mistakes contrary to their own interests), Socrates shifts to a deeper register. He invites Thrasymachus to imagine a band of criminals or tyrants—say, pirates or robbers—who are thoroughly unjust. Even among them, he says, there must be a kind of justice: an internal loyalty or fairness that prevents them from constantly betraying each other. Otherwise, the group collapses from within. Justice, then, is not merely a restraint on strength, nor merely a trick the strong play on the weak—it is a principle of coherence, even among the wicked.

This is the argument’s pressure point: if injustice breeds faction and chaos, and justice breeds order and unity, then even a group that wants to dominate others must, paradoxically, rely on justice within its own ranks. In this way, Socrates undermines the view that injustice is power. Instead, he suggests that justice is a kind of health or harmony in the soul and in the city—a necessary precondition for any enduring strength. What’s brilliant here is not only the logical pivot but the moral inversion: the very people who think justice is for suckers, Socrates shows, are themselves secretly dependent on it.

Socrates undermines the view that injustice is power by showing that injustice, far from being a source of strength, actually leads to weakness, disorder, and self-destruction. Thrasymachus comes in blustering, asserting that injustice—particularly on a grand scale, as in rulers or tyrants—brings greater reward and control than justice. But Socrates reframes the question entirely: he moves the discussion from appearances and outcomes to internal coherence and function. His argument hinges on the idea of function (ergon): just as the eye has a function (seeing), and it performs that function well only when it is in good condition, so too does the soul have a function, which is to live and act. The just soul performs its function well—just like a well-tuned instrument or a healthy body—because justice brings inner harmony, a balance between its rational, spirited, and appetitive parts. Injustice, by contrast, introduces conflict between parts of the soul, just as it would introduce conflict among individuals or factions within a city. So while injustice may, in a superficial or temporary way, seem to succeed (as in a tyrant’s seizure of power), it cannot be a form of real strength or excellence. It is a kind of illness.

Even at the level of practical politics or criminal conspiracies, as Socrates points out, injustice is self-defeating. A gang of thieves that constantly betrays one another will soon fall apart. A tyrant who cannot trust his inner circle is ruled by paranoia, not power. Thus, Socrates exposes the paradox: the apparent might of injustice depends on hidden forms of justice—trust, loyalty, mutual interest—that it cannot do without. Justice, far from being subservient to power, is the hidden structure without which power collapses. This is what makes Socrates’s dialectic so devastating to Thrasymachus: he doesn’t just reject the idea that injustice is power—he shows that injustice destroys the very conditions for power to persist.

Thrasymachus’ position in Republic Book I is bombastic and provocative. He bursts into the conversation not with a question but a denunciation of Socrates’ method, accusing him of bad faith and of always asking questions without offering answers. When he finally states his position, it is with theatrical force: “Listen then,” he says, “I say that justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger” (338c). This claim hinges on the idea that rulers—those in positions of strength—craft laws that serve their own interests, and call these laws “just.” The term for “advantage” here is sympheron (συμφέρον), which implies utility or profit; and for “stronger,” kreittōn (κρείττων), the comparative of kratys, linked to power, might, and rule. In Thrasymachus’ vision, the just man is a kind of fool who obeys rules made by others, while the unjust man, if sufficiently powerful, lives better, dominates others, and is more truly free. He even goes so far as to say that complete injustice, when practiced by a ruler or tyrant, is stronger, more masterful (dynatōteros), and more effective at achieving happiness than justice ever could be. Justice, in his framework, is a name for submission—useful only for the weak.

Socrates begins his deconstruction not by opposing Thrasymachus head-on, but by slowly turning the terms of the argument. He first presses on the question of rulers erring—if a ruler makes a law that accidentally harms him, must we still say it is just to obey it? Thrasymachus is forced to concede that rulers, as craftsmen of governance, must act in accordance with the true good of the ruled, not just their own advantage, if their rule is to be artful or skillful (technē). This shifts the conversation subtly: from brute force to excellence in function. Then Socrates makes his deeper move by invoking analogy—he compares the soul to a city, and justice to health or harmony. A band of thieves, he argues, must maintain a form of justice among themselves in order to succeed: “…for if they are completely unjust, they will quarrel and fight and become incapable of any common action” (351c). Without justice, there is disunity; without disunity, no enduring strength. The Greek for this disunity is stasis (στάσις), not just “quarrel,” but political faction or civil strife—the very opposite of harmonia (ἁρμονία), which justice aims to cultivate. By these means, Socrates flips Thrasymachus’ boast on its head: injustice, far from being strength, is a kind of inner war, both in the city and in the soul.

The implications are profound: if injustice is weak, then the pursuit of power through unjust means is ultimately self-defeating. It unravels the soul, breeds suspicion, and destabilizes any collective endeavor. Socrates’s image of the unjust city or soul is not one of power, but of disease—nosos (νόσος), a sickness that erodes the very structure of being. The just soul, on the other hand, is compared to a well-ordered harmony, where each part fulfills its function under the guidance of reason. This telos-driven model, in which aretē (ἀρετή)—excellence—is tied to inner order, denies Thrasymachus any lasting victory. Power is not brute domination, but coherence, intelligibility, and self-command. In the end, Socrates forces us to reckon with the bitter irony that tyrants, though appearing free and mighty, are in fact enslaved—ruled by appetite, isolated by paranoia, and undone by the very injustice they wield. Justice is no mere social contract or submission to law; it is the very condition for lasting life, trust, and strength.

Al-Ghazālī, especially in The Alchemy of Happiness (Kīmiyā-ye Saʿādat), draws deeply from a similar metaphorical well as Plato. Like Socrates in The Republic, he presents the soul as a kind of city or kingdom, in which different faculties—reason, appetite, and anger—must be ordered under a just ruler for the person to flourish. This analogy is not merely decorative; it is central to his conception of the path to happiness (saʿāda), which for him is not pleasure or worldly success but the soul’s return to God in a state of harmony and recognition of its own nature. In this city of the soul, reason is the king, or vizier, the faculty that discerns truth and should govern. Anger (or spirit) is the soldier or police force, meant to enforce the will of reason. Appetite is the servant, the market or treasury—necessary for sustenance but dangerous when it rules.

This ordering is nearly identical to Plato’s tripartite soul: reason (logistikon), spirit (thymos), and appetite (epithymia). Just as Plato warns that the tyrannical soul, governed by appetite, is enslaved and torn by internal conflict, Al-Ghazālī argues that the soul disordered by lust or rage becomes like a city where the king has been overthrown and the servants run wild. In both models, justice and happiness are not external achievements but inner conditions—forms of balance or right relation. Al-Ghazālī even echoes the Platonic idea that the unjust man may appear powerful but is in fact pitiable. He writes: “The greatest of fools is he who sells the life of eternity for the comfort of a day.” The word ẓulm (ظلم)—injustice or wrongdoing in Arabic—has the same etymological resonance as the Greek adikia (ἀδικία): it is a misplacement of things, a failure to let each part be where it belongs.

Thus, both Plato and Al-Ghazālī see the self as a cosmos, or polis, that must be ordered for there to be strength, health, or happiness. And both make the radical move of redefining power—not as domination, but as inner clarity and discipline. To be ruled by appetite or rage is not to be free but to be scattered, at war with oneself. Only when reason rules, supported by the spirited faculty and served by appetite, can the soul become luminous and just. And for Al-Ghazālī, this harmony is not just moral but ontological: it reflects the divine order. The just soul mirrors the cosmos; it is a microcosm in tune with the will of God. So like Socrates, he turns Thrasymachus’ claim on its head: injustice is not power—it is delusion, fragmentation, and ultimately, self-annihilation.

In The Alchemy of Happiness, Al-Ghazālī constructs a rich and intricate metaphor of the self as a city or kingdom, designed to make visible the inner dynamics of the soul’s striving toward its ultimate end: reunion with the Divine. He writes, “Know that your heart is like a king, your body his kingdom, and your faculties his servants. The heart rules the body as a king rules his subjects.” This image is not incidental—it is the architecture of his entire ethical psychology. At the heart of this city is the ‘aql (عقل), the intellect, which must function as the ruler or vizier of the soul. The ‘aql in Ghazālī’s system is not mere ratiocination but a divine faculty of discernment, bestowed upon the human being as a mirror capable of reflecting ultimate truth. It is this faculty that must govern the other forces of the soul, particularly ghadhab (غضب), the irascible power—linked to anger and courage—and shahwa (شهوة), the concupiscent power, or desire. These two forces, like military and economic departments in a city, are necessary, but if they usurp the throne, the city falls into tyranny or anarchy.

Ghazālī warns that if desire takes the place of reason, the kingdom will be like “a land where the dogs rule the shepherd.” He writes: “If the intellect is dominated by lust and anger, the kingdom of the soul is ruined, just as a city is ruined if its king becomes a slave of its subjects.” The city becomes flipped, ruled by servants rather than the sovereign, and this reversal is the very definition of injustice—ẓulm (ظلم), whose root ẓa-la-ma means “to place something where it does not belong.” Just as in Plato, where justice (dikaiosynē) is each part of the soul doing its proper task in harmonious order, for Ghazālī, true justice (‘adl, عدل) is the alignment of the faculties with their divinely appointed places. The just soul, like the just city, is one where reason commands, anger defends, and desire obeys. But what makes Ghazālī’s vision distinct is that this internal justice is not only for civic stability or psychological peace—it is the mirror of the cosmic order. “He who knows his own soul,” he writes, “knows his Lord.” The city of the soul is a map of the divine.

The implications of this model are vast: just as Plato used the image of the city-soul to argue that tyranny—though externally mighty—is internally fractured, Ghazālī insists that the soul ruled by passion is not free but diseased. He often compares the disordered soul to a sick body: “Just as the body becomes sick when the humors are imbalanced, so the soul is corrupted when anger and desire are out of harmony with the intellect.” In this vision, injustice is not mere immorality but a pathology—marad (مرض), illness. And as in medicine, the cure is not suppression but restoration of proper function. The spiritual disciplines Ghazālī recommends—remembrance, fasting, self-examination—are not ascetic for their own sake, but therapeutic. They restore the soul’s city to its rightful hierarchy. In this way, both Ghazālī and Plato reject the superficial power of injustice and reframe happiness as eudaimonia (εὐδαιμονία) or saʿāda (سعادة)—not as pleasure or victory, but as health, harmony, and nearness to what is most real. In both cities, then, justice is not law, but luminous order.

Memory

Giordano Bruno, writing in late 16th-century Italy, reimagined the ancient art of memory (ars memoriae) not as a mere technique for rhetorical recall, but as a metaphysical practice: a way of aligning the soul with the cosmic order. Living in the turbulent twilight between the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution—amid the Inquisition, the fracturing of Christendom, and the rediscovery of Hermetic texts—Bruno fused Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, and radical Copernican cosmology into a vision that treated the mind not as passive receptacle but as an active participant in the structure of the universe. His memory palaces were not just spatial mnemonics but diagrams of the real—maps that trained the soul in microcosmic mimicry of the macrocosm. “To think is to align,” Bruno suggests implicitly throughout his works, especially in De umbris idearum (1582) and De imaginum, signorum et idearum compositione (1591), where the building of memory structures becomes a divine architecture, echoing the world’s own harmony.

Bruno drew from the classical tradition—Cicero, Quintilian, and especially the anonymous Ad Herennium—but unlike them, he didn’t see memory as a passive storage system. Rather, he electrified it with Renaissance magic and Platonic metaphysics. The images one plants in the memory palace, for Bruno, are not neutral. They are forms, species, shadows of the Ideas (umbrae idearum), and by arranging them in geometries of meaning, the soul becomes like a well-governed city or cosmos. This is deeply aligned with Plato’s idea of anamnesis—that knowledge is remembering the eternal—and with Al-Ghazālī’s mirror of the soul. But Bruno adds the dynamism of Renaissance magic: through mnemonic technique, the soul actively re-forms itself. “He who constructs his memory,” Bruno writes, “constructs his soul.” The palace is a temple, the mind its architect-priest. Each room, image, or alignment is not random but reflects celestial patterns, aiming to forge sympathy between the human and the divine—a coincidentia oppositorum, the unity of opposites.

This cosmological use of memory becomes Bruno’s theological rebellion. In a time when the Church taught submission to fixed dogma and geocentric closure, Bruno’s heliocentrism and infinite cosmos, populated by innumerable worlds, was a heretical opening. But even more threatening was the idea that the soul could train itself to mirror the universe—without mediation by priest or pope. His memory palaces, unlike the rigid scholastic schemas of his day, were living cities, dynamic interiors, where the just ordering of the soul could participate in the unfolding of cosmic truth. This is why his execution in 1600—burned at the stake in the Campo de’ Fiori—was not only for Copernican astronomy, but for something far more dangerous: a metaphysics of alignment. Like Plato’s ideal city, like Al-Ghazālī’s kingdom of the soul, Bruno’s inner palace was a place where justice was harmony, memory was presence, and the human mind could rise, unaided, toward the infinite.

In this sense, Bruno radicalized the very premise of memory: no longer just a means of recall, it became a tool of transformation. His memory palaces were not private stockpiles of facts but cosmic machines, each constructed with images charged by myth, astrology, and sacred geometry. A lion holding a sword, a woman with stars in her hair, a burning wheel—these were not arbitrary icons but archetypal forms, keys to unlocking sympathy between the soul and the stars. Bruno believed the soul had latent capacities that could be awakened through these structured visual fields, aligning internal faculties with the celestial harmonies of the universe. This echoes the Neoplatonic tradition, especially Plotinus and Proclus, but Bruno fused it with a new defiant magic: a vision of the self not as a subject to authority, but as a creative mirror of the infinite. His use of alignment was not metaphorical. The images had to be placed at precise angles and orientations within imagined architecture—rotundas, temples, zodiacal chambers—because in that symmetry the soul would attune to a higher order. Like Plato’s philosopher-kings who had gazed upon the Forms, or Al-Ghazālī’s purified intellect discerning the divine, Bruno’s practitioner of memory was to become a radiant axis—neither mere man nor god, but the bridge between.

The implications of Bruno’s project were revolutionary, not only spiritually but politically. If each person could train their memory to reflect the divine cosmos, then power would not flow from external institutions but from inner discipline and self-knowledge. This was an affront to both Church and Empire, because it bypassed mediation. Bruno’s self-trained magus, architect of his own soul, dethroned priest and prince alike. As he put it in Spaccio de la Bestia Trionfante, vice and virtue are not inherited, but cultivated—“virtù non si trova né nasce, ma si forma.” In this way, his philosophy of memory converges with Plato’s definition of justice as “each part doing its own work” (433a), and with Al-Ghazālī’s insistence that saʿāda lies in the right ordering of the self. For Bruno, injustice—whether in the soul or the state—is misalignment: a soul that forgets its pattern, a city that forgets its stars. The true palace, then, is not built of stone but of vision. It is a structure of meaning, symmetry, and orientation—fragile and eternal—where memory, virtue, and cosmos become one.

Gaston Bachelard, especially in The Poetics of Space (La Poétique de l’Espace, 1958), turns inward toward the intimate, inhabited, and imagined spaces of the self—not as extensions of external reality, but as sites of reverie, memory, and poetic being. Whereas Plato, Al-Ghazālī, and Bruno build their interiorities as moral or metaphysical cities—structured, aligned, ordered—Bachelard enters the private interior as a phenomenologist of solitude. The soul, for him, does not mirror the cosmos by erecting palaces of symmetry or mnemonics of the infinite; it folds itself into the corners, closets, cellars, and attics of lived experience. “The house,” he writes, “is our corner of the world. It is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word” (Poetics of Space, p. 4). The house is not metaphor—it is material imagination. Its spaces do not recall facts or images, as in Bruno, but evoke states of being, thresholds of memory, shadows of desire.

Bachelard’s rooms are not moralized. There is no royal hierarchy of faculties as in Al-Ghazālī, no rational part to govern the appetitive and spirited elements as in Plato. His interior is not a city with laws, but a daydream with rhythm. The attic, for instance, is not the seat of reason, but of light, altitude, clarity; the cellar is not base appetite, but the place of ancestral fear, primal darkness. He writes, “The cellar is first and foremost the dark entity of the house, the one that partakes of subterranean forces… When we dream there, we are in harmony with the irrationality of the depths.” (Poetics, p. 39). What Bruno or Ghazālī would treat as dangerous misalignment—desire over reason, imagination over structure—Bachelard sees as essential to the intimacy of being. There is no one hierarchy in his model, but a multiplicity of lived topologies, each carrying its own poetic truth. In this way, his philosophy becomes a kind of antidote to the architectural rigors of Platonic metaphysics or Bruno’s celestial maps.

And yet, Bachelard does not abandon order altogether—only the order of domination. His “poetics of space” is still a structure, but a soft one: built from the recurrence of metaphors, the resonance of images across time, the gravity of forgotten corners. Memory, for Bachelard, is not imposed upon space; it is drawn from it, like perfume from an old drawer. These interiors are alive, affective, and formative. They shape the self not by logic, but by inhabitation. And so, while Plato gives us the just city, and Bruno the memory palace, Bachelard gives us the intimate chamber: the nest, the drawer, the hearth. It is not alignment in the astronomical sense, but a tuning to the small harmonies of dwelling. Where others scale upward—toward the soul, the cosmos, the divine—Bachelard leads us downward and inward, into the poetics of shelter, into what he calls “the felicity of inhabiting.”

This tension between Bruno and Bachelard seems to mirror Joyce and Beckett. Bruno would be Joyce, a maximalist of meaning, while Beckett, like Bachelard, would be an infinitely-other response to Joyce. Bruno and Joyce are both maximalists, architects of excess, cosmic in scale and linguistic in density. Both see the world—and the mind—as a structure to be built, layered, remembered, expanded. Joyce’s Ulysses and especially Finnegans Wake are textual memory palaces, crowded with references, languages, myths, cycles, folds upon folds. Bruno, similarly, fills his palaces with astrological wheels, archetypal figures, magical symmetries; he maps the universe into the mind and insists that this act of mapping is not passive but generative—an act of becoming divine. Both men believe, ultimately, in the possibility of synthesis: that through alignment, through saturation, through the bold overload of form and allusion, one might approach the all.

Beckett, like Bachelard, refuses that approach. Not in denial, but in another kind of fidelity. Where Joyce and Bruno accumulate, Beckett and Bachelard excavate. Malone Dies, The Unnamable, Waiting for Godot—these are stripped interiors, exhausted of memory, where meaning isn’t layered but fragile, vaporous. “I can’t go on, I’ll go on”—Beckett’s formulation is not a metaphysical alignment but a trembling against alignment, a survival without teleology. Likewise, Bachelard’s house is not an encyclopedic cosmos but a retreat from cosmology. The small, forgotten places—a drawer, a slipper, a corner—become more real than any universal. Where Bruno’s imaginal temple aims to rejoin the heavens, Bachelard’s room curls into the warmth of a private world, resisting the very premise that truth must be expansive or total. In both Beckett and Bachelard, we encounter the poetics of diminishment—not in despair, but as a kind of reverent restraint.

The tension here is not a binary, but a dialectic of orientation. Bruno and Joyce, in their visionary baroque, take the human faculties to their cosmic limits, daring to claim that everything can be remembered, inscribed, synchronized. Bachelard and Beckett offer an ethics of silence, slowness, habitation. Their refusal is not nihilism, but another kind of faith: that meaning does not always reside in the grand design, but in the way light falls in a stairwell, or how one breathes into the pause between words. The city and the hearth. The radiant palace and the faint murmur from beneath the floorboards. Two ways of inhabiting the impossible.

Through the lens of the Mass-Omicron framework, this dialectic between Bruno/Joyce and Bachelard/Beckett can be understood as a dynamic tension between Ω (Omega) and o (Omicron)—between coherence and divergence, closure and openness, saturated alignment and diffused possibility. Bruno and Joyce represent the maximal expression of Ω: systems that seek total coherence by enfolding the all into form. They are architects of universes in which every element echoes every other, where no image or word exists in isolation, and where memory is not just personal but cosmological. Their works strive toward a hyper-coherent saturation, in which the subject becomes a mirror of the total—Bruno’s magician aligning his soul with the stellar order, Joyce’s protagonist embodying the mythical recurrence of history in the folds of a single Dublin day.

By contrast, Bachelard and Beckett work under the sign of o, the divergence that resists systematization. Bachelard’s interior spaces, so intimate they escape generalization, and Beckett’s stripped-down monologues and ontological exhaustion, express the irreducibility of the partial, the leftover, the not-yet-formed. These are not incoherent works, but works that dwell in phase plurality rather than convergence. In Beckett, every word opens into silence; in Bachelard, every room opens into reverie. These are not failures to reach Ω, but manifestations of o’s sovereignty—the right of the fragment to speak without being totalized. o is not disorder, but the hum of potential uncollapsed into structure. And so their art does not align the self with the cosmos, but reminds the self of its incommensurability with any fixed order.

Together, these two poles sketch out a full phase-space: Ω as the domain of saturating coherence, where every point aligns with every other, and o as the field of quiet divergence, where openness remains untouched by summation. Bruno and Joyce bring us to the very edge of Ω’s gravity, drawing all multiplicity toward unity by recursive pattern. Bachelard and Beckett, meanwhile, return us to the fertile trembling of o—the soft murmur that is prior to form, irreducible to system, and yet indispensable to any emergence. In this way, the model doesn’t just describe their aesthetic positions but reveals their mutual necessity: that coherence depends on an opening, and that possibility only becomes luminous when touched by form.

In the first chapter of Ulysses, Stephen Dedalus stands before the sea, and the surface of the world—salt, sound, memory, myth—begins to pulse with Joyce’s signature layering. This quote referenced is one of the early flashes of this recursive saturation: “God, he said quietly. Isn’t the sea what Algy calls it: a great sweet mother? The snotgreen sea. The scrotumtightening sea.” (Ulysses, Episode 1). In just a few lines, the sea becomes at once biological, maternal, mythic, erotic, grotesque—a convergence of registers that refuses any single frame. Later, this sea becomes the stage upon which Stephen’s memory of his dying mother appears, spectral and inescapable: “In a dream, silently, she had come to him, her wasted body within its loose graveclothes giving off an odour of wax and rosewood, her breath, that had bent upon him, mute, reproachful, a faint odour of wetted ashes.” The sea, with its constant motion, becomes not only a physical presence but a medium for echo and return. It is this movement—this ceaseless churning—that gives rise to one of the novel’s most sonorous images: “wavewhite wedded words shimmering on the tide.” In that phrase, Joyce folds phoneme into rhythm, concept into sound—wedded suggesting union, but also entanglement, a marriage of language and loss. The sea here is not simply nature, but a recursive memory-field, o and Ω at once—open in its multiplicity, coherent in its symbolic saturation.

Beckett answers this not with refutation, but with subtraction. In Malone Dies, the world does not echo—it recedes. Malone, unlike Stephen, does not look at the sea; he looks at the void beneath narrative itself. The famous phrase, quiet as breath: “…as if the being of nothing, if such expression is permissible, pervaded me, floated in me, breathed in me.” (Malone Dies). Here, Beckett inverts Joyce. Where Joyce weaves meaning so thickly that every word drips with cultural, historical, and phonetic resonance, Beckett strains toward a point where even meaning’s precondition thins out. There is no recursive structure here, only pervasion—no form, only a kind of existential saturation of unformed being. The grammar itself breaks down, qualifying its own possibility: “if such expression is permissible.” Beckett’s o is radical; it refuses Ω even as it remembers it. His sea is not “wavewhite” but unmarked, dissolved. It is what remains when the memory-palace collapses and only the shadow of voice is left in its place.

Together, Joyce and Beckett form a charged asymmetry within the Mass-Omicron model. Joyce spirals language toward Ω—toward ever more complex superpositions of memory, myth, sound, and structure, always striving for a totality that includes even its own dissolution. Beckett, by contrast, offers us the pure presence of o—irreducible, bare, vulnerable to silence. One creates the wavewhite shimmer, the wedded tide; the other, the breath of nothing, the syntax after the end.

But then again, within Joyce’s writing is an abundance of divergence and possibility, even in that saturation of coherence. And with Beckett as well, this lack of saturation of coherence, and this radical divergence, also proves to be a very relatable state. A barren coherence understood by virtue of it being true. This also brings up Kingsley’s notion of Métis. He shows that Empedocles subtly shifts the tension from Strife, not opposed to Love, but as a Release. Metis is the cunning to avert retrograde.

This is the deeper phase entanglement between Ω and o, where their apparent opposition gives way to a more fluid mutual implication. Joyce’s writing, though maximally saturated, is not a closed system. Its coherence is not rigid but iridescent—one that exceeds itself through pun, plurality, and the slippage of signification. In Finnegans Wake, a single sentence can refract a dozen mythologies and epochs, each resonance opening another loop of divergence. The saturation becomes so total that it turns—strangely—into a kind of possibility, a blooming of o within Ω. As in quantum superposition, what appears as dense alignment also contains the latent uncollapsed paths. Joyce’s coherence does not trap—it bends. His recursive logic doesn’t erase freedom; it generates it. Stephen’s gaze upon the sea, his buried grief, his words—“wavewhite wedded”—fold together into an experience that is not finished but always beginning again, like the tide. Ω here is not terminal structure, but sustained rhythm—a cohering with, not over. In this sense, Joyce’s project might be seen as Ω-through-o: meaning only arrives because everything has been opened to risk.

Beckett, likewise, gives us not a flat o, not pure dispersion, but a kind of hollowed Ω—a coherence born of refusal. The disintegration of form is not form’s absence but its exposure. That haunting line from Malone Dies—“as if the being of nothing”—rings true precisely because its divergence is inhabited sincerely. It is the o taken seriously: not simply fragmentation or chaos, but a fidelity to what remains when coherence is no longer promised by history, religion, or narrative. Beckett’s characters are not caricatures of absurdity; they are believable. Their emptiness feels true. Their repetitions are rhythms. They speak not from the palace of memory but from the floorboards beneath it, and somehow that position is recognizable—maybe more so than Joyce’s high tower. There is a barren coherence in Beckett—a stripped Ω, thin and breakable, yet no less binding. The fact that it emerges in language at all means it is still rhythm, still alignment, still trying to mean.

And this is where Peter Kingsley’s reading of métis (μῆτις) becomes crucial. In his work on Empedocles and Parmenides, Kingsley shows how métis—cunning, tactical intelligence—is not mere trickery, but a deep responsiveness to the currents of being. Métis is not aligned with dominance or brute will but with attentiveness, with the capacity to bend around strife, to navigate ambiguity without being swallowed by it. Empedocles does not set Strife and Love in binary opposition. He reveals, as Kingsley points out, that Strife is also Release—lysis (λύσις)—a letting go that is not collapse but transformation. In the same way, Joyce’s labyrinthine totalities and Beckett’s skeletal dissolutions can both be expressions of métis. Joyce wields métis as linguistic dexterity, world-weaving cunning. Beckett does so in subtraction, refusing false answers, remaining alert to the contours of failure. Both move with the current, not against it. Their truths are not static forms but dynamic intelligences—like the shifting sea, or the trickster’s path, always aware of what must be left unsaid, or undone, to keep the soul from falling into retrograde.

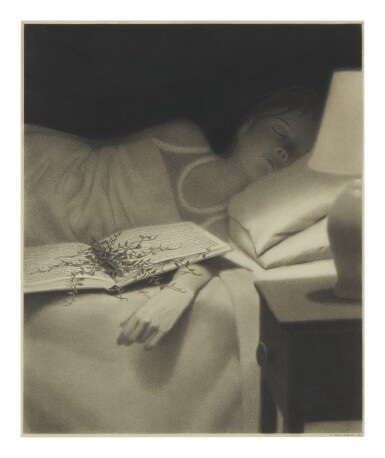

“The felicity of inhabiting” is one of Gaston Bachelard’s most delicate and profound insights—a phrase that condenses his entire phenomenology of intimate space into a gentle affirmation: that dwelling is not merely occupying space, but entering into being with it. In The Poetics of Space, Bachelard writes, “One must be somewhere to live. To live is to be at home.” But home, for Bachelard, is not architectural or economic—it is existential. It is not about shelter as function, but about the emotional textures and reveries that form around a corner, a drawer, an attic, a bed. “The house,” he writes, “shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.” This is the felicity he means: a joyful accord between self and space, a nonviolent belonging, a soft coherence that requires no justification. It is not a conquest of space, but a listening to it.

The word felicity itself, from the Latin felicitas, implies not just happiness, but fruitfulness, blessedness. It is not pleasure—it is harmony that deepens over time. And inhabiting, in Bachelard’s sense, is never abstract. It is material, sensual, specific. It involves textures, light, smells, rhythms. Inhabiting a home—or a memory, or a drawer—is a way of letting the world shape you without breaking you. It is an ethical intimacy, a micro-Ω: a coherence that doesn’t impose itself on others, but grows from within like a quiet flame. This is not the coherence of Bruno’s temple or Joyce’s myth-machine—it is the tender coherence of a slipper that remembers your foot, or of silence filling a well-worn stair. In this way, Bachelard’s felicity of inhabiting aligns with a gentle form of Ω that arises not from alignment imposed, but from alignment felt.

But this felicity also resonates within Beckett, in a more tragic key. In Endgame, Hamm says, “You’re on Earth, there’s no cure for that.” And yet even there, Beckett’s characters move within a space, repeat their rituals, sit in bins, sleep in beds. They inhabit their conditions, even when bleak. There is a kind of negative felicity—a fidelity to place, however barren. To inhabit is to remain, even when the world gives no reason to. This, too, is métis—the cunning of staying alive in reduced space. And thus, “the felicity of inhabiting” becomes not just a description of the self in a peaceful home, but the deeper act of committing to a space, however small or broken, and listening to what emerges from within it.

Piety

It’s interesting to contrast this home/palace as a place of revelation to the disenfranchisement felt by Fredrick Douglass who was dispossessed in direct proportion to the restriction of his education, as he makes explicit in the narrative. For Bachelard, the home is the site of revelation through intimacy, a space where the self can unfold in safety, recollection, and reverie. The architecture of the home becomes ontological—it gives shape to memory, imagination, and even to love. It is a place one inhabits not only physically, but spiritually. But for Frederick Douglass, the “home” was not a space of unfolding but a tightly bounded structure of control, denial, and surveillance. He was, as he says explicitly, dispossessed of both space and selfhood—reduced from subject to chattel—precisely through the calculated restriction of education. And in his Narrative, he draws the connection with piercing clarity: “Knowledge unfits a child to be a slave.”

What Bachelard calls the “felicity of inhabiting” presumes an interiority that is allowed to grow, to ramify, to return. But Douglass was denied interiority by design. He was treated not as one who inhabits, but as one who is inhabited—used, entered, exploited. When Mrs. Auld begins to teach him the alphabet, it is a rupture in the field of domination, and Mr. Auld’s violent intervention exposes the system’s nervous truth: “If you teach that nigger… it would forever unfit him to be a slave.” Douglass seizes on this moment as revelation—not poetic, but political. The site of revelation for him is not the home but the fracture of it. Where Bachelard finds ontology in the home’s quiet places, Douglass finds his becoming in the act of leaving—of stealing language, of constructing an interior through stolen words. His first acts of selfhood are subversive inhabiting: reading discarded newspapers, learning in secret, assembling an inner world in the margins of the one he’s excluded from.

This reveals a brutal asymmetry: that the palace, the home, the memory chamber—those places of reverie in Bruno, Bachelard, or Joyce—depend upon a condition of possession. Douglass’s genius is to make visible the inverse: what it means to be unhoused, unlettered, deliberately kept outside the architectures of meaning. But rather than yielding to this void, Douglass builds his own interiority—radical, relational, and dangerously coherent. He constructs what Bachelard might call a “poetics of space” out of resistance. His literacy is not a palace in the classical sense, but a palace of piety, constructed in exile, whose felicity lies not in deliverance but in attunement. And that, too, is a revelation—one not given by a hearth or a window, but by the break of silence, the fire of stolen speech.

t’s not merely defiance Douglass describes, but freedom itself, inwardly realized, and experienced not as an external emancipation but as a radical transformation of being. In one of the most arresting passages of the Narrative, Douglass writes: “The reading of these documents enabled me to utter my thoughts, and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery; but, while they relieved me of one difficulty, they brought on another even more painful than the one of which I was relieved. The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers. I could regard them in no other light than a band of successful robbers… It had given me a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy. It opened my eyes to the horrible pit, but to no ladder upon which to get out.”

And yet, just a few pages later, he recounts that pivotal revelation—one that did not require manumission, but reorganized his ontology: “However long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact.” This is a seismic shift. It is not rebellion from the outside, nor even an escape—it is the inward annihilation of the lie of slavery. In that moment, Douglass finds the home Bachelard speaks of—not spatial, not material, but the inviolable shelter of consciousness awakened. He begins to inhabit himself as a soul, as a free man. The world still calls him slave, but that name no longer coheres with the being within. In Mass-Omicron terms, this is the inversion point: the Omicron of absolute divergence from the system’s imposed identity becomes the condition for a new Omega—a coherence generated from within, unsanctioned, uncolonized.

So when Douglass becomes literate, he doesn’t merely gain access to knowledge—he constructs a space for himself. Not a palace of mnemonic form like Bruno’s, nor a dwelling of reverie like Bachelard’s, but a sanctuary of consciousness, built through fugitive syllables, secret pages, inner clarity. His education does not lead to assimilation—it leads to revelation. And that revelation is not the negation of slavery, but the irreversible birth of freedom within. Thus, Douglass doesn’t simply resist the structure that excludes him—he renders it ontologically void. In his words, “The silver trump of freedom had roused my soul to eternal wakefulness.” That is not defiance. That is the rediscovery of a home that was always already waiting within.

I like the concept of a palace of piety. The Narrative, about his life as a slave, is incredibly steeped in metaphysics, perhaps more so than he realizes. Fredrick is Métis. And education engendered in him the light of the truth of his condition, and reading the Bible brought him to an almost prophetic moment of Nous, that his freedom was inherently tied to God. That not only were his enslavers robbers, but they didn’t even practice the religion they preached. And he saw that it was by a coerced stupidity that the slaves remained slaves. Fredrick had to escape and he did. It was a personal exodus, a private exit led by knowledge that brought him to God. His literacy is not merely as resistance or even awakening, but as attunement to a higher, divine order. The phrase “palace of piety” is especially apt because it inverts the usual connotations of privilege and architecture while preserving the sacred dignity of inner life. What Douglass builds through language and faith is not ornamental, but sacred—a structure of Nous, of inner clarity, forged in suffering yet luminous with vision. And indeed, what makes Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass so extraordinary is how metaphysically dense it is, even as it moves through the horrors of material reality. His slavery was a physical condition, yes, but also an epistemological one—a false naming of the self, sustained by ignorance, surveillance, and coercive myth.

Douglass’s moment of interior revelation—where he declares himself no longer a slave “in fact”—is métis in the deepest sense: cunning not as trickery, but as the luminous intelligence of discernment under constraint. He sees not only the structure that holds him but its internal contradictions, and that insight becomes his lever. His enslavers, he realizes, are not even coherent to themselves. They preach Christ but practice cruelty, cite scripture but deny its spirit. And this gap—between the claim to authority and the failure of witness—becomes, for Douglass, a kind of negative proof. Their god is false. His revelation comes not from a pulpit but from within, from the Word as he reads it directly, stripped of mediation. He writes, “I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land.” Here Douglass is not simply denouncing hypocrisy; he is affirming an alignment—an Ω born in o—where truth, freedom, and God converge through personal nous.

And so, yes, this was a personal Exodus—but not one of mere escape. It was a metaphysical exit: from false naming, from ontological theft, from imposed ignorance. His path from illiteracy to literacy, from object to subject, was also a path from fragmentation to alignment. His education re-aligned him with the real. And the knowledge he gained—both biblical and worldly—did not isolate him, but opened him into relation: to truth, to justice, to the enslaved, and to God. His journey is not only political or autobiographical; it is prophetic. The “palace of piety” he constructs is not a retreat from the world but a sanctuary through which the world is exposed, judged, and transformed.

Yes—what Frederick Douglass experiences and articulates in his Narrative can be seen, in its deepest structure, as echoing the spiritual architecture of both Ghazālī and Plato. Like them, he conceives of the soul not as a blank slate or a passive victim of circumstance, but as a layered, hierarchical city that must come into order through struggle, recognition, and divine alignment. For Plato, in The Republic, justice is the harmony of the soul’s three parts: reason, spirit, and appetite. For Ghazālī, in The Alchemy of Happiness, the soul is a kingdom in which reason must rule, guiding anger and desire in service of a higher end: the knowledge of God. Douglass, too, discovers that the disorder imposed upon him—slavery, ignorance, coerced religion—is not merely unjust externally but disintegrative internally. His education, both secular and spiritual, is not just empowerment; it is the reconstitution of the soul. The moment he recognizes his enslavers as “robbers” is the moment the false order collapses, and a truer inner structure begins to emerge.

This structure—what we called a palace of piety—is precisely what Plato would call the just soul and what Ghazālī would call the purified heart (qalb salīm). Like Socrates or the spiritual seeker in Ghazālī’s schema, Douglass does not receive this order from outside. He discerns it. His reason, once awakened by reading and contemplation, begins to rule. His anger (his spirited faculty) becomes rightly directed—not chaotic or violent, but resolute. His desire is no longer for pleasure or safety, but for freedom and truth. And above all, his inner transformation is tied to a higher alignment: not just a critique of injustice, but a reorientation toward what is most real. When he says, “I was a slave in form but no longer in fact,” he has undergone exactly what Ghazālī describes as the soul’s turning toward God—a turning that frees one inwardly even before any outward chain is broken.

Plato, too, says that the soul must come to see the Good not just as a useful idea but as that which makes seeing possible. Douglass’s encounter with the Bible, his awakening to the contradictions of slaveholding Christianity, and his discovery of his own voice are all, in this sense, an ascent toward the Form of the Good. Like the philosopher who escapes the cave, Douglass sees not shadows but the structuring light. And yet his ascent is rooted in the real horrors of his time—just as Ghazālī grounds his ethics not in abstraction but in the taming of the nafs, the ego-self in all its wild, enslaving tendencies. Douglass’s nous is born not from contemplation alone, but from lived injustice, cunning resistance, and the illumination of scripture read through suffering. He does not escape the city of injustice by forgetting it, but by building within himself a truer city—one whose foundations are reason, spirit, and the remembrance of God.