"Well, this is Krypton. Nobody knows what the people on Krypton look like. What if we look like bagels, but I'm going to make my son look like a human because that's where I'm sending him – to Earth – but everybody else on Krypton looks like bagels. That would really be original." - Marlon Brando

Engels said it was about "three guys, who used to be cows, living in Van Nuys and trying to assimilate their lives." Harry Dean Stanton was attached to star and he and David Lynch tried to convince Marlon Brando to co-star, but Brando was not interested, calling the script "pretentious bullshit".

“Acting is the expression of a neurotic impulse. It’s a bum’s life. The principal benefit acting has afforded me is the money to pay for my psychoanalysis.”

(From an interview in 1973, reflecting his complex view of the profession.)

——

In “Freud and the Scene of Writing,” Derrida seizes on Freud’s brief reflection about the child’s “mystic writing-pad”—a wax tablet covered by a thin celluloid sheet—to argue that psychic life is structured like writing rather than like speech. Press a stylus on the pad and a dark mark appears; lift the sheet and the surface seems blank again, yet the recessed wax preserves every earlier trace. For Derrida this double operation of inscription and erasure turns the Freudian unconscious into something very like a palimpsest: an ever-thickening stratigraphy of marks that can be overwritten without being annihilated. Memory, desire, repression, even the sudden irruption of a symptom all depend on this layered economy of traces that persist precisely through partial effacement.

Because those residual marks never fully vanish, presence is always already contaminated by absence, and the conscious “scene” of psychic life is only the uppermost translucent layer of a parchment whose under-texts ceaselessly condition what can surface. Derrida radicalizes Freud’s model by insisting that such differential inscription precedes the classical subject itself: what we call “I” is merely a provisional fold in an indefinitely rewritable text. The unconscious, therefore, is not a dark chamber that stores fixed contents but the very spacing—what Derrida names différance—through which every sign takes its place while referring to other, earlier, half-erased signs. To read the psyche is thus to read a palimpsest whose prior writings can never be fully restored yet can never be fully silenced, sustaining both the possibility and the impossibility of a definitive interpretation.

Freud’s “mystic writing-pad,” Derrida maintains, is not merely a convenient metaphor for memory but a miniature technical apparatus that exposes a logic of inscription operating beneath both psychic and linguistic life. The upper celluloid sheet embodies consciousness, capable of being wiped “clean” at every moment, while the wax slab underneath embodies unconscious latency, holding indelible grooves that any new mark must trace across, displace, or deepen. Between the two strata runs a thin film of air that temporarily insulates them, allowing fresh writing to happen without obliterating prior engravings; Derrida seizes on that tiny gap as the site of différance itself—an interval where the trace is constituted by deferral and spacing. Memory is thus a technical effect before it is an interior faculty: what seems like subjective recollection in Freud’s topography is re-grounded as a machinic relay of surfaces, pressures, and supports that together generate the illusion of a continuous present. Far from housing pristine “original” impressions, the psyche turns out to be produced through iterated supplementations, each new layer both conserving and rewriting what came before, so the very idea of an origin recedes into an asymptotic depth beyond retrieval.

This model forces a rethinking of psychoanalytic interpretation itself. If every symptomatic manifestation is already a palimpsestic overlay, the analyst is confronted not with a concealed core waiting to be uncovered but with a sedimented archive whose strata are mutually contaminating. The dream-work, repression, and deferred action (Nachträglichkeit) become, in Derrida’s view, operations of textual editing: substitutions, condensations, and displacements that never stabilize into final meaning but perpetually re-contextualize earlier traces. Reading a dream or a slip of the tongue therefore resembles deciphering a manuscript whose margins, erasures, and overwritten passages are as significant as the legible lines. By framing the unconscious as this ceaseless scene of writing, Derrida dislodges any hope for a full recovery of truth and instead locates psychic reality in the play of differences that keep sense both possible and undecidable, making every analytic act a provisional inscription upon an already over-inscribed page.

Picture the Etch A Sketch: inside the red frame a thin layer of silvery powder coats the glass, and a hidden stylus—moved by the twin knobs—scrapes that coating away to reveal dark lines. Each twist of the knobs engraves a groove in the powder that will stay there permanently, yet the picture appears only so long as the exposed glass is visible. Shake the toy and the loose powder resettles, re-covering the etched furrows so the screen looks blank again, ready for fresh drawing. Derrida would seize on precisely that double movement—simultaneous inscription and erasure—as a living illustration of the palimpsest-logic he draws from Freud’s “mystic writing-pad.” What seems to disappear never truly vanishes; it sinks one layer down, becoming an invisible relief that silently guides or resists every new line. Conscious thought is the fleeting image on the surface, unconscious memory the network of buried channels beneath, and the thin film of powder drifting between them is the spacing of différance itself—the interval that both divides and connects presence with its own effaced history.

Just as the shaken Etch A Sketch never quite loses the micro-grooves that were cut into its powder, experience never ceases to impress subtle ridges upon the psychic substrate. Even when an event seems to vanish from recall, its granular relief continues to contour the paths along which fresh perceptions travel, bending them toward certain associations while diverting them from others. In Derrida’s terms, every act of erasure is already a reinscription: the newly leveled surface gains its very smoothness from redistributed traces that remain active beneath the eye. What we call forgetting, therefore, is less a deletion than a re-coating—a delicate diffusion that masks without cancelling, ensuring that what was once present will persist as a pressure shaping how presence itself can come to appear.

This layered persistence means that interpretation can never hope to expose a single hidden stratum where meaning sits intact; the moment one brushes away the silvery dust to “see what’s underneath,” the interpretive gesture deposits new particles that alter the relief yet again. Analysis is forever implicated in the scene it tries to read, adding its own strokes while trying to discern the former ones. For Derrida the ethical task is not to unearth a pure origin but to remain attentive to that ceaseless interplay of covering and uncovering—to read the folds, acknowledge the sedimented past, and accept that clarity always arrives at the cost of another partial eclipse. The Etch A Sketch, like Freud’s writing-pad, thus stages a restless economy in which the trace survives only by being perpetually overwritten, and where the most faithful reading is one that keeps listening for the faint, unmetabolized tremors still echoing beneath the apparently blank screen.

In “La parole soufflée” Derrida turns to Antonin Artaud’s letters, manifestos, and theatrical delirium to stage a drama of voice that is never simply one’s own. The phrase can mean both “speech blown away” and “speech blown into,” capturing Artaud’s conviction that language is a site of violent pneumatics: voices invade him like gusts, seizing his breath, while his own utterances are expelled into a void that immediately swallows them. Derrida seizes on this doubled economy to dismantle the classical opposition between inspired logos (living, interior, self-possessed) and derivative writing (dead, exterior, alienable). If Artaud’s “theatre of cruelty” dreams of recovering a pure, pre-symbolic cry, Derrida shows that the very desire for an unmediated voice betrays its impossible condition: speech is already a ventriloquism, a chain of borrowed breaths, so every attempt to secure presence ends in expropriation. The schizophrenic torment Artaud records—feeling “spoken through” by foreign forces—thus exposes what the sane subject normally forgets: that articulation is constituted by a spacing where the self is both emitter and echo, origin and citation.

From this perspective the scene of language resembles the palimpsest logic Derrida elsewhere locates in Freud’s mystic writing-pad. Each spoken word is a stratum laid down over earlier murmurs that it cannot erase; the “I” that speaks is already hollowed out by archival grooves and by the anonymous air—souffle—that carries phonemes to ear and page. Artaud’s resistance to this condition, his savage attempt to wrench language back from the “plagiarists of spirit,” is what Derrida calls a metaphysics of reappropriation, doomed because it posits a property of meaning that never existed. Yet in failing, Artaud’s theater illuminates the general law: meaning survives only by being both inhaled and exhaled, stolen and surrendered, an oscillation that binds body to script without final reconciliation. “La parole soufflée” therefore radicalizes Derrida’s critique of presence: it insists that the most intimate breath is already iterability in motion, a current whose very passage ungrounds any fantasy of a voice uncontaminated by the others that keep it alive.

Artaud’s torment, Derrida suggests, lays bare the constitutive impurity of genesis itself: every seeming origin of speech has already been punctured by echoes, borrowed breath, and the refractory medium of writing. The same current that carries a shout outward also propagates it as trace, so the desire to reclaim a pristine, pre-scriptural voice always rebounds into further différance. By following Artaud’s oscillation between ecstatic expulsion and invasive possession, Derrida shows that “presence” is not a fullness waiting to be expressed but a precarious syncopation, achieved only in the momentary balance between exhalation and the return wind that hollows it. What unsettles Artaud—feeling plagiarized by the very air—is thus, for Derrida, the normal condition of signification: the interval where the living body becomes legible precisely because it is traversed by absences that mark and suspend it.

This insight folds back on critical practice. To read Artaud is not to mine his texts for a hidden core of authentic suffering but to attend to the way each manifesto, letter, or performance fractures under the strain of its own aspiration to immediacy. The critic’s task, in Derrida’s view, is to inhabit that fracture without sealing it, allowing the displaced breaths—those pauses, ruptures, and italicized screams—to register as constitutive rather than accidental. Interpretation thus joins Artaud’s theatre in refusing the comfort of a stable vantage point; it must accept that the act of explicating a text inevitably recycles the very ventriloquism it exposes, sending new currents through the script and further dispersing the voice it seeks to fix. In this sense “La parole soufflée” is less a commentary on Artaud than an enactment of the same aeronautics of meaning, demonstrating that critique, too, can only speak by yielding to the play of forces that undo any final possession of the word.

Theater of Cruelty

“In a close-up, the audience is only inches away, and your face becomes the stage.”

Antonin Artaud’s “Théâtre de la cruauté” names less a taste for gore than a radical wager on theatrical intensity. By “cruelty” he meant an implacable rigor that strips away the psychological comfort and linguistic padding of bourgeois drama, forcing performer and spectator alike to confront the raw forces—desire, fear, cosmic indifference—that culture suppresses. Artaud envisioned a stage where speech would no longer reign as transparent vehicle of meaning but would fracture into cries, guttural phonemes, incantations; gesture, light, and percussive sound would batter the senses, choreographing a tempest that bypasses polite comprehension and strikes the body directly. In this storm the actor becomes a kind of living hieroglyph, dissolving the boundary between ritual and performance so that theater again approaches the status of sacred ordeal.

Cruelty, for Artaud, thus names a metaphysics of absolute involvement. It opposes the Cartesian split between mind and flesh by insisting that every thought is already carnal, every symbol already tattooed upon nerves and viscera. To enact cruelty is to accept that creation demands sacrifice: the destruction of conventional language, of comforting representation—and, if necessary, of the performer’s own psychic skin—in order to release a deeper vitality. The audience, drawn into this vortex, is not invited to empathize with fictional characters but compelled to sense the trembling architecture of their own drives and anxieties. In place of catharsis, which purges emotion through narrative resolution, Artaud proposes contagion: an unmediated transfer of affect that leaves no safe distance from the stage.

Derrida, reading Artaud in “La parole soufflée,” seizes on this program as proof that the yearning for unmediated presence is itself haunted by mediation. The very breath that carries Artaud’s anti-textual screams is already a relay of borrowed air, infiltrated by the spacing of différance. Hence the Theater of Cruelty simultaneously exposes and founders upon the impossibility of escaping the writing that it tries to burn away; its furious gestures overwrite older traces only by inscribing new ones in their place. Yet precisely in that failure the project succeeds: it reveals, with visceral clarity, that meaning lives in the fracture between impulse and articulation, in the moment a voice both possesses and abandons the body that emits it.

Historically, Artaud realized only fragments of this vision—most notably in the 1935 production of Les Cenci—before illness and exile intervened. But his manifestos detonated across post-war performance: Grotowski’s “poor theatre,” Brook’s Marat/Sade, the sonic assaults of The Living Theatre, even aspects of contemporary immersive and performance-art practice all trace lines back to the laboratory Artaud proposed. Each inherits his core demand—that theater abolish the polite proscenium and become an event of risk where word, gesture, and audience share the same trembling stake—while grappling, as he did, with the paradox that every attempt to tear language open inevitably writes another chapter in its endlessly palimpsestic book.

Artaud’s insistence on cruelty forces a reckoning with the very grammar of spectatorship: the audience is no longer a detached eye gazing across a proscenium but a corporeal participant whose nervous system becomes the stage on which the drama actually happens. When light, percussion, and convulsive gesture collide in the theater-space, they short-circuit the semiotic distance that normally protects viewers, compelling them to experience meaning as somatic shock rather than conceptual translation. This collapse of aesthetic mediation, Artaud believed, could reopen the door to rites that ancient cultures enacted in communal trances or blood sacrifices, dissolving the boundary between spectacle and sacrament. In that sense cruelty is not a taste for violence but a method for relocating theater in the fragile juncture where body, myth, and cosmos intersect—and where language can no longer pretend to arbitrate the real.

Yet the very extremity of the program clarifies its ethical stakes. If theater becomes a laboratory that manipulates breath, pulse, and dread, it risks reproducing the authoritarian energies it seeks to expose; every attempt to shatter representation must confront the possibility that raw affect, once unleashed, can be weaponized by power as readily as it can liberate. The post-war directors who adapted Artaud—Grotowski, Kantor, Brook—tempered cruelty with rigorous craft, framing the sensory assault within disciplined dramaturgies so that intensity served inquiry rather than domination. Today, immersive installations, VR performances, and activist street spectacles revisit Artaud’s wager under digital conditions, exploring how mediated environments can still shock bodies into new perceptions without collapsing into mere spectacle. The enduring question his theater poses is therefore double: how to reach a strata of experience deeper than discourse, and how to do so without forfeiting the critical distance that allows bodies, once shaken, to reflect on what has moved them.

Bertolt Brecht counter-poised a fundamentally different wager on theatrical truth from Artaud’s sensory tempest. Where the Theater of Cruelty sought to overwhelm spectators into visceral involvement, Brecht’s “epic theater” sought to prise them loose from enchantment, installing a reflective interval—his celebrated Verfremdungseffekt—between stage and auditorium. By breaking the fourth wall with placards, songs, and abrupt shifts of tone, Brecht flaunted the machinery of representation so that audiences would perceive every scene as a construct and judge the social relations it displayed. He wanted spectators not to feel with characters but to watch them as historical specimens, asking at every moment: “Could it be otherwise?” This detachment was not aesthetic coldness but a Marxist pedagogy; only by interrupting empathy, Brecht believed, could theater illuminate the transformability of conditions that bourgeois drama naturalized as fate.

Technically, epic theater borrowed from montage and cabaret, deploying stark lighting, projected statistics, even actors who stepped out of role to narrate their own actions. Such devices fractured narrative continuity in order to foreground Gestus—the gestural crystallization of a social attitude—thus translating class relations into intelligible form. The result is a writing-on-stage that remains visible as writing, a kind of palimpsest whose layers (story, commentary, historical data) never collapse into seamless illusion. In this Brecht unwittingly anticipates Derrida’s insistence that meaning subsists in the spacing of traces: the alienation effect is itself a spacing engineered to keep the signifier from melting into presence. Yet whereas Derrida views that gap as an ontological precondition of any sign, Brecht wields it as a political instrument, a deliberate fissure through which spectators might glimpse the ideological stitching and choose, afterward, to unpick it in the world beyond the theater doors.

Brecht’s alienation devices work only because they exploit the same mimetic circuitry they then interrupt: music, story, emotional charge still draw the audience in, but just as identification begins to settle, a song lyric, a projected statistic, or an actor’s direct address interrupts the affective loop and throws the newly formed empathy back into thought. That recoil—what Brecht called “gestic thinking”—turns the stage into a laboratory where familiar motives become visible as performative choices rather than natural inevitabilities. By insisting that every gesture is both personal and historical, he exposes the social choreography embedded in habits of love, work, and obedience; spectators come to see themselves as participants in an unfinished script that can be edited rather than as consumers of a finished story. The stage thus becomes a palimpsest of possible futures: each intervention erases the illusion of necessity only to inscribe a provisional alternative, inviting the audience to continue rewriting once they leave the theater.

Epic theater’s durability lies in this oscillation between immersion and critique, which later practitioners—from Godard’s filmic jump cuts to Lehrstück-influenced performance art—have adapted to new media and political climates. Its political charge does not stem from delivering a correct message but from demonstrating how any message is constructed, rehearsed, and therefore alterable. In that sense Brecht converges with Derrida’s insight that presence is always mediated by trace, yet he operationalizes that ontology for strategic ends: if meaning is inevitably spaced, then theater can widen the gaps at key moments to expose where power has sutured contradiction. The lesson is not merely analytic; it is performative and pedagogical, modeling how citizens might keep a similar estranged vigilance in everyday life, prying open the intervals where habit conceals contingency and where, as Brecht put it, “the world can be changed and made better.”

Konstantin Stanislavsky’s lifelong project was to rescue the stage from what he saw as the empty bombast of late-nineteenth-century melodrama by returning it to a felt, organic truth. Working at the Moscow Art Theatre from the 1890s onward, he devised a rigorously psycho-physical rehearsal process that asked actors first to absorb the “given circumstances” of the play—its social setting, historical moment, and material details—then to thread those facts through their own sensorium until an authentic inner logic emerged. The goal was not raw autobiography but a disciplined synthesis in which memory, imagination, and bodily action fused into a single through-line, the character’s super-objective. Early iterations emphasized “emotion memory,” the conscious recollection of personal feeling to kindle stage reality; later Stanislavsky shifted toward “the method of physical actions,” grounding motivation in concrete tasks that summon emotion indirectly, like sparks awakened by friction rather than by will. Either way, his system made presence the prize: when the score of tiny objectives clicks into place, the actor seems to live spontaneously in circumstances scripted decades earlier, and the audience, sensing no seam, forgets it is watching artifice at all.

That devotion to seamless illusion places Stanislavsky at the opposite pole from Brecht’s alienation effect and Artaud’s sensory assault. Where Brecht interrupts empathy to provoke critical distance, and Artaud blows language apart to jolt the nervous system, Stanislavsky cultivates identification so deep it feels transparent; spectators are invited to inhabit, not dissect, another life. Yet beneath the surface of “naturalness” lies a stratified rehearsal notebook—a sequence of beats, tempo-rhythms, and psychological score—not unlike the palimpsest Derrida finds in Freud’s mystic writing-pad. Each performance writes itself on that hidden under-text, subtly overwriting prior choices while preserving their grooves as potential cues, so that what appears immediate is in fact a layered artifact of earlier inscriptions. In this sense Stanislavsky does not banish the trace; he choreographs it so meticulously that it dissolves into living gesture, rendering the machinery invisible precisely when it is working at its most intricate.

The legacy of that disappearing machinery is enormous. Exported through émigré teachers like Richard Boleslavsky and later retooled by Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, and Sanford Meisner, Stanislavsky’s principles mutated into the various American “Method” schools that shaped mid-twentieth-century cinema and still dominate realistic acting today. At their best these descendants preserve his ethical conviction that truthful art can cultivate empathy across class, culture, and even time; at their worst they reduce a sophisticated psycho-physical dialectic to a cult of personal feeling. Yet the core insight endures: to move an audience one must first construct an inner scaffolding strong enough to bear the weight of fiction without collapse, then let that scaffold vanish in the instant of performance. What Stanislavsky offers, against both Artaud’s extremity and Brecht’s strategic fracture, is the possibility that immersive illusion—far from anesthetizing thought—can awaken a quiet, contemplative form of recognition, where spectators discover the overlooked humanity in actions that feel as inevitable as their own heartbeat.

Stella Adler carried Stanislavsky’s project across the Atlantic but pruned away the inward-curling vine of private emotional recall that Lee Strasberg had grafted onto it. After observing Stanislavsky’s late “method of physical actions” in Paris during the 1930s, she returned to New York convinced that the key to truthful acting lay not in mining personal trauma but in fertilizing the imagination with the play’s social vista—the who, what, where, and when that Stanislavsky called the given circumstances. Adler told her students that an actor’s own life was too small to house Shakespeare or Odets; they had to conjure worlds vaster than their autobiography by researching history, architecture, music, and gesture until those external facts ignited an inner flame. Where Strasberg’s Method prized cathartic self-exposure, Adler demanded disciplined expansion, insisting that craft begins when the actor “creates beyond the self and therefore becomes more fully oneself.”

That outward-facing discipline gave her studio a double charge: pedagogical rigor and political sweep. By asking actors to excavate the social stakes embedded in a text, Adler anticipated Brecht’s gestic analysis, yet she refused to estrange feeling from action; the audience, she believed, thinks with its senses. Her emphasis on imaginative breadth echoed Artaud’s call for theater to tap mythic energies, but she funneled that energy through meticulous script analysis rather than ritual shock. In practice the Adlerian actor builds a layered palimpsest: historical research lays the first parchment, sensory exercises inscribe the second, rehearsal choices etch the third, and performance writes over them all while leaving each stratum faintly legible beneath the next. The result, at its best—as in the early work of Marlon Brando or the later range of Viola Davis—is a stage presence that feels both immediate and mysteriously populated by worlds beyond the actor’s skin, a living testament to Adler’s credo that “growth as an actor and growth as a human being are synonymous.”

New York

“Acting is the least mysterious of all crafts. Whenever we want something from somebody or when we want to hide something or pretend, we're acting. Most people do it all day long.”

New York’s theatre district in the early-to-mid-1930s was a paradoxical place: the Great Depression had emptied box offices, yet it also incubated an unprecedented surge of collectivist experiment. The Federal Theatre Project, launched in 1935 as part of Roosevelt’s New Deal, put thousands of unemployed artists back to work, subsidising “Living Newspaper” docudramas and racially integrated ensembles that played to audiences who had never seen a stage before. This climate of public subsidy and political urgency lent moral weight to aesthetic innovation and convinced a generation of young actors that theatre could be more than entertainment—it could be social intervention.

Into that crucible stepped the Group Theatre, founded in 1931 by Harold Clurman, Cheryl Crawford and Lee Strasberg. Modelled on Stanislavsky yet committed to contemporary American stories, the Group drilled like a commune each summer, rehearsing Odets’s Awake and Sing! or Waiting for Lefty until the actors’ private impulses meshed into what Clurman called a single “pulse-beat.” Elia Kazan—an earnest stagehand turned bit-player—found his vocation here, first as an actor in those ensemble pieces and soon as a resident director, staging Robert Ardrey’s Casey Jones (1938) and Thunder Rock (1939) with a muscular, propulsive energy that classmates nicknamed “Gadge’s” trademark.

When the Group unraveled under wartime economics and Hollywood temptation, Kazan helped salvage its method by founding, with Crawford and Robert Lewis, the Actors Studio on West 44th Street in 1947. There the apprenticeship system hardened into a laboratory: actors worked behind closed doors, testing scenes until private motivation fused with public gesture—the process later popularised (and hotly disputed) as “the Method.” Stella Adler, who taught across town, stressed imaginative reach; Strasberg, now the Studio’s artistic chair, emphasised affective memory; Kazan, straddling both camps, insisted on the director as midwife who shapes those volatile techniques into clear event.

Success on Broadway—A Streetcar Named Desire in 1947—catapulted Kazan to Hollywood, but his 1952 testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee, naming eight former Communist colleagues, shattered the solidarity that had nurtured him. Many peers never forgave the betrayal; others noted that the ordeal sharpened his art, driving him toward fiercely personal films such as On the Waterfront (1954), whose informer-hero mirrors the director’s own self-justification. The controversy crystallised New York’s post-war rift: progressive theatre veterans who saw themselves as inheritors of the WPA’s democratic spirit versus Cold-War liberals who, like Kazan, recast artistic freedom as a bulwark against totalitarianism.

By the late 1950s the palimpsest was set: Adler’s classrooms on Central Park West championed a socially imaginative naturalism; Strasberg’s Studio refined a more introverted psychologism; and Kazan, oscillating between Broadway and film, leveraged both currents to invent a new American style—intimate, urgent, ethically fraught. The city that had once hosted subsidised agit-prop now exported psychologically electrified realism to every screen in the country, yet the invisible grooves of the 1930s remained: each rehearsal, each political choice, traced over earlier inscriptions that still guided—sometimes resisted—the next bold stroke.

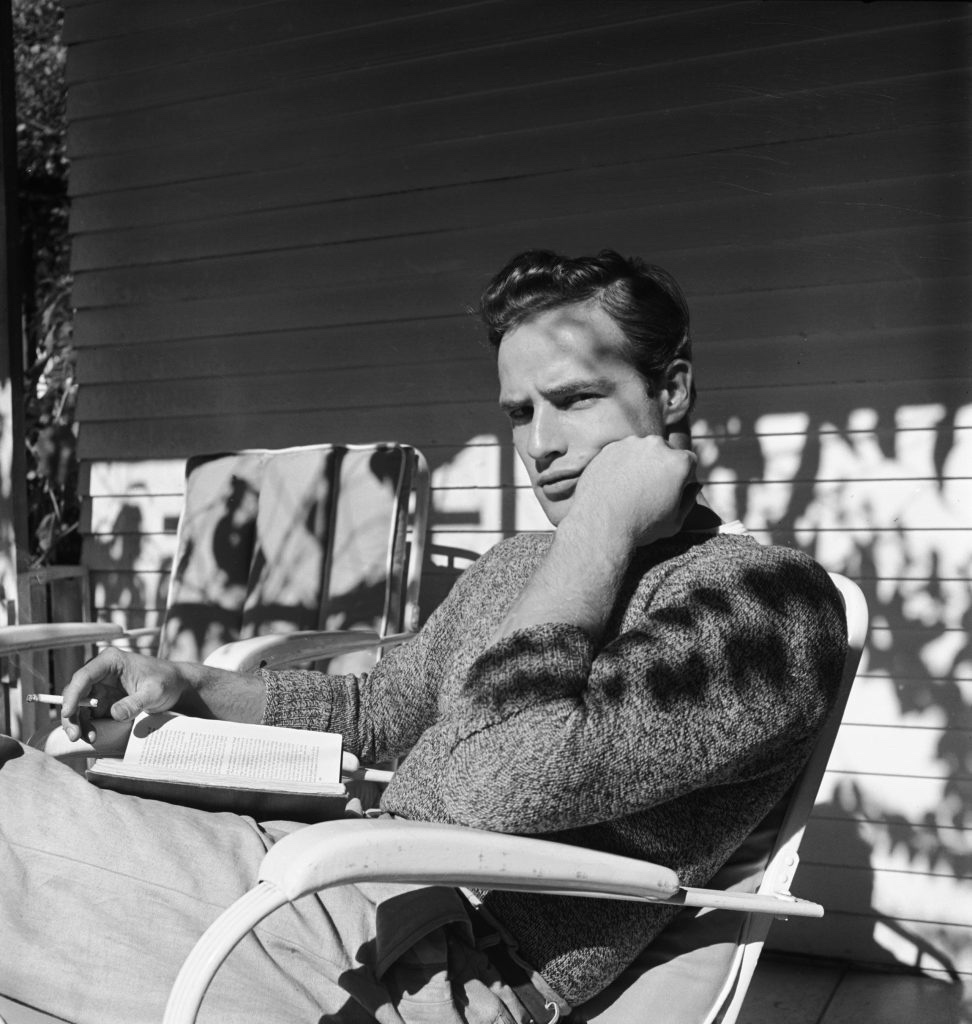

Late in August 1947 Elia Kazan put a penniless 23-year-old Marlon Brando on a bus—Brando spent the fare on food and hitch-hiked instead—to Tennessee Williams’s rented cottage in Provincetown. Three days after he was expected, the actor banged through the door to find the house dark and the toilet overflowing. Without saying a line he replaced a blown fuse, unclogged the drain, and only then read a scene from A Streetcar Named Desire. Williams, half-drunk and skeptical of so young a Stanley, needed barely half a minute: he later called it “the most magnificent reading I ever heard” and pressed bus money into Brando’s hand so he could race back to New York and sign the contract .

That Provincetown audition reshaped the play itself. In a letter to his agent Audrey Wood two days later (29 August 1947) Williams exulted that they had found “such a God-sent Stanley in the person of Brando.” Casting a man still in his early twenties, he explained, “humanizes the character… it becomes the brutality of youth rather than a vicious older man,” turning the drama into “a tragedy of misunderstandings and insensitivity” rather than a simple clash between villain and victim . The playwright, who had first imagined Stanley as a heavier, middle-aged brute in the John Garfield mold, now trimmed dialogue and stage directions to let Brando’s physical grace and sexual volatility register; Stanley’s swagger, sudden tenderness toward Stella, and even the famous “Stella!” eruption were calibrated around the actor’s feline energy.

Brando’s presence continued to guide rehearsals with Kazan. His restless movement, muttered asides and half-swallowed lines persuaded Williams to leave many expository moments implicit, sharpening the play’s erotic undertow and making Stanley as compelling as Blanche. After the Broadway opening the fusion of Williams’s revised text and Brando’s animal vitality fixed the role so indelibly that later critics would say actors had to work “under the ghost of Brando” whenever they approached the part . In short, the plumber’s-handed hitch-hiker from Omaha did more than win a role; he shifted Williams’s vision of the Kowalski-DuBois battle from cardboard brutality to a dangerously seductive collision of youth, sex, and class, leaving the script forever scored with the grooves of that first incandescent reading.

Brando

“At Field Elementary School in Omaha, I'd been the only one in my class to flunk kindergarten; I don't remember why”

Born on April 3 1944 in Omaha, Marlon Brando grew up wrestling with an alcoholic mother, a domineering salesman father, and a restless streak that got him expelled from Shattuck Military Academy. Unable to enlist because of a knee injury, he followed his actress-sisters to New York in 1943 and plunged into the Dramatic Workshop at the New School, where Erwin Piscator drilled students in political naturalism and Stella Adler introduced him to Stanislavsky’s imaginative method. Adler’s demand that actors “create beyond the self” electrified Brando; classmates already spoke of the burly Midwesterner who mumbled through scenes until some inner fuse lit and the room went very still.

Within three years Brando had made his Broadway debut in I Remember Mama (1944), collected Theatre World Awards for Candida and Truckline Café (both 1946), and forged ties with Group-Theatre veterans Harold Clurman and Elia Kazan. In Truckline Café—Clurman directing, Kazan producing—he ran up Belasco Theatre stairs before every entrance to arrive onstage sweating and half-feral, a performance critics found unsettling and thrilling in equal measure. Those nights fixed his reputation as the most urgent young actor in New York: rebellious off-stage, physically explosive on it, and already shaping a new, psychologically jagged idiom of realism.

By the summer of 1947, then, Brando was a 23-year-old phenomenon living hand-to-mouth in a borrowed cold-water flat yet orbiting the city’s hottest directors. Kazan dispatched him to Provincetown to read for Tennessee Williams’s still-unfinished A Streetcar Named Desire. Brando hitch-hiked, arrived days late to a beach house with no power or plumbing, calmly rewired the fuse box and unclogged the toilet, then delivered a reading so incandescent that the playwright rewrote Stanley Kowalski as younger, sexier, and disarmingly vulnerable. At that moment Brando’s own contradictions—Midwestern tenderness and streetwise menace, technical craft and anarchic impulse—coalesced into the role that would make both actor and playwright immortal.

A Streetcar Named Desire

“You have to know what the truth is before you can lie about it convincingly.”

Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire opens with Blanche DuBois, a once-aristocratic schoolteacher from Laurel, Mississippi, stepping off a shabby New Orleans streetcar—first “Desire,” then “Cemeteries,” and finally “Elysian Fields”—to visit her younger sister Stella. Blanche is fleeing scandal: the DuBois family home, Belle Reve, has been lost to creditors, and she has been dismissed from her teaching post after an affair with a teenage student. Clinging to silk dresses, high-flown language, and the flicker of paper lanterns, she tries to preserve the illusion of Southern gentility that once defined her, but the Kowalskis’ cramped, working-class flat throbs with a different rhythm—jazz, poker, raw sexuality—and her fantasy collides at once with the crude vitality of Stella’s husband, Stanley.

Stanley Kowalski immediately suspects Blanche is hiding money from the sale of Belle Reve and rummages through her trunk to expose what he calls her “lies and tricks.” Their standoff intensifies over successive poker nights, drunken outbursts, and humid afternoons in which Stanley’s dominance over the household becomes ever clearer. Stella is caught between loyalty to her sister and fiercely erotic attachment to her husband, the play’s central triangle echoing the broader clash between a fading antebellum mythos and post-war industrial America. Blanche’s one hope for rescue arrives in Stanley’s friend Harold “Mitch” Mitchell, a shy bachelor whose gentleness seems to promise the stability she craves. Yet when Stanley uncovers the full extent of Blanche’s past—her adolescent husband’s suicide, her ostracism from Laurel for multiple sexual liaisons—he ruins her courtship with Mitch by revealing the truth during a climactic poker night.

The final act unfolds during Stella’s childbirth. Blanche, alone in the apartment, tries to steady herself with fantasies of a wealthy benefactor named Shep Huntleigh, imagining a telegram summoning her to sanctuary. Stanley returns from the hospital victorious, drunk, and territorial; the scene turns predatory, and he rapes Blanche, shattering the last fragile veil between her and reality. When Stella learns what has happened, she refuses to believe it—for to side with Blanche would mean abandoning her marriage. Instead, she allows Stanley to arrange Blanche’s committal to a state asylum. The play concludes with Blanche, dressed in a tarnished bridal gown, being gently escorted away, murmuring her famous line about depending “on the kindness of strangers,” while Stella sobs on the stair yet returns, numbly, to Stanley’s embrace.

Williams threads this domestic tragedy with motifs of desire and death, light and shadow, truth and illusion. Blanche’s streetcar ride is both literal and symbolic: she is propelled by eros toward self-destruction, unable to disembark once momentum gathers. Stanley, for his part, embodies the brutal clarity of a world that has no patience for fading grandeur; his victory is complete, yet Williams leaves us uncertain whether the cost—Stella’s complicity, Mitch’s disillusionment, Blanche’s erasure—is tolerable. What remains is a humid, haunted tableau of post-war America in which tenderness and violence share the same narrow rooms, and where the fragile refuge of illusion flickers out under a stark, naked bulb.

Blanche’s tragedy is that the powder of forgetfulness never quite settles over the grooves already cut into her psyche, so every fresh attempt at self-reinvention merely skims a thin, shimmering layer across furrows that remain fully intact. The rape of her young husband by scandal, the humiliations in Laurel, even the faint perfume of lost Belle Reve lie beneath her coquettish Southern diction like the dark lines beneath a shaken Etch A Sketch screen: invisible from the right angle, yet unmistakably embossed. Each time she slips on silk, dims the lamp, or spins a story about “Shep Huntleigh,” she is tilting the toy, hoping the powder will drift evenly enough to hide the scars, yet the slightest jolt—Stanley rifling her trunk, Mitch’s porch light snapping on—scrapes the upper coating away, exposing the under-writing with merciless clarity.

What destroys her, then, is not simply Stanley’s brutality but the structural cruelty of inscription itself: history keeps writing her even as she tries to write over it, and the spacing between these layers becomes a site of unbearable tension. Under the naked bulb she is forced to inhabit both surfaces at once—the trembling, manic performance of Southern gentility and the harsh relief of trauma that presses upward through every smile. In Derridean terms, she is trapped in différance without the luxury of repression; the trace insists on itself, refusing full erasure or full legibility. The asylum’s white coat at the close is merely another shaky overlay, destined, like all the others, to reveal the grooves it pretends to cover.

Blanche’s desperate flirtations, her fragile décor of paper lanterns and soft jazz, are not empty affectations but improvised techniques of surface management. She orchestrates light, sound, and language the way an Etch A Sketch user twists the knobs, trying to redraw the visible pattern faster than memory can seep through. Yet her tools are inadequate to the velocity of the shocks she encounters in the Kowalski apartment. The more fiercely she dusts the screen with powdered charm, the more violently Stanley’s interrogations vibrate the frame, shaking the coating loose. The mismatch between her limited control over appearance and the inexhaustible depth of earlier cuts leaves her suspended in a perpetual feedback loop: every new story she invents to obscure the past merely deepens the cognitive dissonance when the next jolt reveals the lingering lines beneath.

This loop shatters her ability to distinguish what is performative from what is real, eroding the border between conscious staging and involuntary recall. As Mitch withdraws, as the paper lantern rips, as Stella leaves with contractions to the hospital, Blanche’s surface-management strategy collapses under its own weight, and the hidden grooves dictate her behavior outright—visionary monologues, hallucinated telegrams, a final surrender to the “doctor” who resembles one more gallant stranger. The asylum awaits not because she fails to forget but because she can never fully re-cover; the protective powder can no longer settle, and the raw wax of her history shows through in jagged relief. Streetcar’s climactic cruelty is that this exposure, once total, is met not with understanding but with systemic erasure: society shakes the frame again, removing the spectacle from view, while the engraved wax—Blanche’s enduring trauma—remains sealed out of sight, beyond the reach of further editing.

Brando does something Shakespearean to Stanley’s character that Tennessee Williams didn’t put into the play. What Brando does is he gives full negative capability to the character of Stanley by providing what could be called dignity to his nature. Stanley Kowalski isn’t just a brute angry poor brother-in-law. Through Brando’s talent Stanley becomes a person who is unwilling to be bedazzled by Blanche’s phoniness, a phoniness that she developed as a result of not being able to come to terms with the things that happened to her in her life. During this time, with Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, the whole atmosphere of jazz and Zen Buddhism, experimental music and modern art culminated in this film where instead of a clash between two very different characters you have an expose on an abused Transatlantic dream of white America. Versus this is the real grit which would set the tone for all of Elia Kazan’s future films (On the Waterfront, East of Eden, Gentleman’s Agreement, etc).

Brando’s rendering of Stanley Kowalski injected a Shakespearean “negative capability”—Keats’s phrase for holding contradictory truths in balance—into a character Williams had drawn mainly as brute force. Because Brando was barely twenty-three, his feral energy came shaded with innocence; critics of the 1947 premiere noticed that he did not soft-pedal Stanley’s violence, yet he also let the audience glimpse a confused young veteran who will not be dazzled by Blanche’s high-born inventions. Tennessee Williams himself wrote, after watching that Provincetown audition, that Brando “humanized the vengeful Stanley,” turning what had seemed one-sided “willful destructiveness” into “the brutality … of youth,” so the moral scale of the play suddenly tilted toward ambiguity rather than easy judgment .

That ambiguity endowed Stanley with something like tragic dignity. Onstage—and still more in Kazan’s 1951 film—Brando’s pauses, half-mumbled lines, and restless prowling suggested a man dimly aware of his own coarseness yet determined not to be fooled by Blanche’s perfume of half-truths. As a result, their encounter feels less like noble victim versus savage oppressor and more like two wounded epistemologies colliding: Blanche’s Etch-A-Sketch glaze of fantasy against Stanley’s demand for documentary proof. The camera reinforces the clash by trapping their bodies in sweat-slick close-ups while Alex North’s cool jazz score mutters beneath, tying the film to the same post-war atmosphere in which Salinger’s Holden rails against “phoniness,” bop musicians stretch harmonic frames, and Zen teachers speak of direct perception.

Kazan seized on Brando’s negative capability to inaugurate the gritty, location-scented realism that would characterize On the Waterfront, East of Eden, and Baby Doll. Even before Streetcar he had vowed, in a 1947 interview, to “discover America” with films shot in “fields, mines, factories”; Brando’s layered Stanley gave him the template—psychological depth fused to working-class texture—that he would refine through the 1950s. In that sense the movie became a hinge between two American myths: the fraying, trans-Atlantic romance of Old South gentility and the raw immediacy of post-industrial streets where truth arrives in sweat-stained T-shirts, not ball gowns. What audiences felt, even if they lacked the vocabulary, was that the film exposed an abused dream of white American nobility and countered it with a muscular realism poised somewhere between jazz improvisation and Zen directness—less judgment, more encounter, no anesthetic.

Brando’s Stanley thus stands at the crossroads of mid-century culture: a figure who can neither wholly condemn Blanche’s ornate self-defenses nor wholeheartedly embrace his own destructive candor. By embodying that tension without resolving it, Brando gave the character the full tragic range normally reserved for Shakespeare’s flawed princes, and he opened a path for Kazan’s later films to explore American life in the same register of violent tenderness, moral fracture, and hard-won grace.

Method

“If you want something from an audience, you give blood to their fantasies. It’s the ultimate hustle.”

The Method germinated in Moscow at the turn of the twentieth century, when Konstantin Stanislavsky began codifying rehearsal techniques that would coax actors to live truthfully “in the given circumstances” rather than declaim heroically from without. By insisting on sensory detail, psychological action, and a score of beats woven through tempo-rhythm, his system re-imagined theatre as the art of interior process, and it quickly superseded the bombastic melodrama then dominant on European stages.

The system’s decisive Atlantic crossing came in 1923, when the Moscow Art Theatre toured New York. Among the dazzled spectators was a young Lee Strasberg, who felt he had witnessed “real thoughts and desires” onstage for the first time. Two company actors, Richard Boleslavsky and Maria Ouspenskaya, stayed behind to teach at the American Laboratory Theatre, planting seeds that would soon sprout in dozens of Manhattan studios.

Those seeds flowered in the Group Theatre (1931 – 41), a Depression-era collective founded by Strasberg, Harold Clurman, and Cheryl Crawford. There, ensemble training, affective-memory drills, and summer-long retreats forged an “American acting technique” that its members simply called the Method. The crucible was as ideological as it was aesthetic—a left-leaning workshop that treated every shrug or silence as social gesture. Tensions soon surfaced: Strasberg pursued ever-deeper excavations of personal memory, while Stella Adler, fresh from studying with Stanislavsky in Paris, championed imaginative research into the play’s outer world; Sanford Meisner broke away to focus on moment-to-moment listening. Yet the Group’s productions—Odets’s Awake and Sing!, for instance—proved that this new interior naturalism could electrify Broadway.

When wartime economics dissolved the Group, Elia Kazan, Crawford, and Robert Lewis founded the Actors Studio in 1947 to “preserve and develop this new American acting” far from box-office pressures. Strasberg assumed artistic control in 1951, refining the Method’s classroom rituals—sense memory, private moments, improvisational “activities”—while Adler and Meisner ran rival studios uptown. The Studio became a private laboratory where professional actors could risk failure, criticize one another without mercy, and search for the flash of lived truth that Stanislavsky had once called “the art of experiencing.”

Method acting burst into public consciousness when Marlon Brando—an Actors Studio habitué who had studied with Adler—created Stanley Kowalski on Broadway in 1947 and on film in 1951. His half-muttered line readings, volcanic physicality, and palpable inner life startled critics and audiences; the screen version was hailed as the first unmistakable appearance of the Method in cinema and helped usher in the era of the morally complex anti-hero.

By the mid-1950s the Method had become shorthand for a new cultural temperature: psychologically raw, socially grounded, suspicious of artifice, and ready for close-up. Whether through Strasberg’s inward archaeology, Adler’s imaginative reach, or Meisner’s kinetic listening, all Method lineages owed their existence to the moment Stanislavsky’s ideas collided with America’s economic turmoil, immigrant ferment, and post-war hunger for authenticity—and in that collision modern screen and stage acting were reborn.

Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty was never meant to traffic in gore; its cruelty lies in refusing the spectator any safe, analgesic distance from what is unfolding. He imagined a stage stripped of literary upholstery—no hermetic proscenium, no politely framed plot—so that gesture, percussion, strobing light, and inarticulate cries could ambush the nervous system and drag the audience into a realm where myth, dream, and trauma interpenetrate. For Artaud the written script is only a scaffolding for a violent alchemy: sound becomes touch, space becomes pressure, language disintegrates into corporeal vibration. The actor, instead of “playing a role,” submits to ritual possession, letting the body channel archaic forces that precede speech. What viewers experience is not catharsis in Aristotle’s sense but a physiological purge that lays bare the psychic circuitry civilized life represses—an ordeal closer to exorcism than to storytelling.

Because cruelty targets the anesthetizing habits of everyday perception, it provokes the very danger Artaud sought: the risk that raw affect, once loosed, might be co-opted by spectacle or power. Post-war directors such as Jerzy Grotowski, Peter Brook, and Tadeusz Kantor engaged that risk by tempering Artaud’s elemental shock with exacting craft, turning the theater into a laboratory where rigor safeguards intensity. In contemporary immersive and performance art, the lineage persists whenever a piece confronts audiences with sensory or ethical thresholds—stroboscopic assaults, durational endurance, participatory rituals—yet frames those thresholds so spectators can reassemble meaning rather than merely suffer stimulus. Cruelty’s lasting lesson is that representation cannot be healed simply by making it more “realistic”; only by cracking the carapace of representation, letting the unsayable flood in, and then demanding reflection on that flood, can theater once again behave like an indispensable rite instead of a decorative diversion.

Artauds original performance had him standing at a podium reading. This could be a precursor to the method. Where, as in Brecht, the fourth wall breaks. All of this, as is discussed in the book Birth of the Cool, was an attempt as living more truthfully, coherence. Ethical happiness, even amidst the exposition of deep pain and grievances.

Artaud’s 1925 Paris recital of L’Evolution de la France—in which he stood behind a lectern, reading aloud while waves of stammering, silence, and sudden crescendo coursed through his body—already forecast the Theatre of Cruelty by treating the podium itself as a pressure chamber. Instead of disappearing into a character, he exposed the very struggle to speak: the voice cracked, the page rustled, the reader’s pulse became audible, and spectators confronted language in the act of breaking down. That performance doesn’t anticipate “Method acting” in the Stanislavsky–Strasberg sense of psychological substitution, yet it does prefigure the Method’s ethical wager: that an actor’s private tremors, laid bare in real time, can restore truth to a medium clogged with rhetorical varnish. By refusing any scenic illusion—no costumes, no set, scarcely a gesture beyond the collapse of syntax—Artaud shattered the fourth wall as surely as Brecht would later do with placards and direct address, though for opposite ends: Brecht seeks analytic distance, Artaud physiological contagion. Both, however, enlist broken form to unstopper experience, believing that spectators who witness an unvarnished process will reacquaint themselves with coherence in a world splintered by industrial warfare and mass spectacle.

That project dovetails with the cultural critique traced in Lewis MacAdams’s Birth of the Cool: jazz improvisers, beat writers, Zen converts, and avant-garde directors all chased a mode of expression that could hold pain without anesthesia, grievance without bitterness, and thereby model a livable freedom. In Artaud’s convulsive reading, the audience meets a speaker stripped down to breath and pulse; in Brando’s Kowalski, viewers sense the raw weather of emotions normally hidden behind scripted polish; in Brecht’s Lehrstücke, citizens rehearse their own contradictions in public view. The common thread is not simply authenticity—as if truth were a stable core to be mined—but the creation of conditions where conflicting layers can resonate without canceling one another. That resonance, Williams might say, is “the kindness of strangers”; MacAdams calls it “cool”; Zen calls it satori; Artaud names it cruelty because it costs comfort to attain. Yet the ethical horizon is the same: a happiness grounded not in denial of wounds but in the skilled circulation of their energies, so the very exposure of deep pain becomes an engine of shared coherence rather than a spectacle of despair.

Artaud’s naked recitation makes clear that the performer’s body is not a transparent conduit for pre-formed meaning but the volatile site where meaning is forged moment by moment. The trembling hand that steadies the page, the vocal crack that suddenly widens the silence, the involuntary sway when breath falters—these are not accidents to be disciplined away; they are the very data the event is designed to register. In this sense Artaud’s lectern functions like the jazz soloist’s microphone or the Actors Studio’s bare rehearsal room: a minimal frame that amplifies micro-fluctuations until the audience can feel thought shifting into gesture, affect condensing into phoneme. What passes between performer and spectator is therefore less a finished statement than an unfinished negotiation of energy, a live demonstration that coherence is emergent rather than imposed. By aligning himself so vulnerably with that emergence, Artaud offers a prototype for later Method actors who risk their private hesitations in front of a crowd, trusting that truthfulness lies not in seamless illusion but in the precision with which oscillations of doubt and conviction are exposed.

Out of that exposure grows an ethics of happiness grounded in mutual recognition. When a room collectively witnesses how fragile the act of making sense can be—and still sees meaning arise—it tests a social hypothesis: that difference and damage need not negate dignity, that pain articulated without anesthesia can enhance, rather than destroy, communal gravity. This is the “cool” MacAdams tracks from Miles Davis’s muted trumpet through John Cage’s indeterminate scores: an equilibrium able to hold forceful opposites in balance, neither suppressing heat nor surrendering to chaos. Brecht cultivates the same poise by suspending narrative to let audiences think; Brando enacts it when Stanley’s cruelty and vulnerability register in the same torn T-shirt; Artaud hammers it into being through guttural cries that resolve, unexpectedly, into lucidity. Each practice demonstrates a path toward coherence that does not deny turmoil but organizes it into shareable rhythm, so that—even amid grievance—the act of collective listening becomes its own modest form of ethical relief.

Marlon Brando arrived in New York with a talent for mischief that matched his volcanic gifts. At the New School’s Dramatic Workshop in 1943 he greeted classmates in half-war-paint, pounded bongos in the corridors, and walked out of Stella Adler’s makeup class just to make the room stare. One peer recalls that Brando “glared and walked out the door” when introduced, only to return a moment later and peel an imaginary apple so convincingly the skin seemed to fall in one unbroken ribbon; Adler rewarded the demonstration with applause while murmuring “lazy boy” at her prodigy. The stunt was typical: Brando delighted in turning routine exercises into impromptu performance art, and his appetite for defiance soon got him expelled from a summer-stock show in Sayville for “erratic, insubordinate behavior.”

On Broadway his sense of play became a physical laboratory. In I Remember Mama (1944) Robert Lewis watched the twenty-year-old newcomer “wander downstage munching an apple” and stand silent for two minutes—yet no one could look away, because every shift of weight and flick of the core signalled inner life. Colleagues began to talk about the “apple test”: if Brando chose to eat onstage, prop or no prop, you suddenly believed he’d lived in that apartment all his life.

The following year Brando’s pranks turned brutal—and brilliant—during Harold Clurman’s rehearsals for Truckline Café. Unable to hear Brando’s mumbling, Clurman ordered him to climb a rope hanging from the flies while shouting a monologue. Brando hauled himself hand-over-hand, roaring the lines in fury; when he dropped to the floor, the previously tentative performance had snapped into fiery focus. Kazan then weaponised the actor’s hyper-kinesis: before each entrance Brando had to sprint up and down the basement stairs, and on opening night Kazan dumped a bucket of water over him so he would stagger onstage “like someone just out of the sea.” The sight left Pauline Kael convinced she was watching someone “having a seizure” until the man beside her whispered, “Watch this guy!”

Brando carried those antics straight into A Streetcar Named Desire. He slept on a cot backstage, boxed with a stagehand between cues—breaking his own nose in the process—and arrived for matinees shirtless and glistening so the odor of sweat became part of Stanley’s aura. The backstage boxing, he said, got him “out of my head and into my fists”; audiences sensed the charge the instant he prowled onstage.

What looks like adolescent prankery was in fact Brando’s early grammar of truth-seeking. Whether peeling phantom fruit, running stairs to the brink of collapse, or goading directors into extreme tactics, he was teaching himself to ignite character through breath and muscle rather than decorative gesture. Those youthful capers seeded the Method with a new principle: if the body is fully engaged, the psyche will follow—and every cracked apple skin, every bucket of water, every busted nose will register on the audience as lived experience, not theatrical effect. Late one night during the 1947 Streetcar rehearsals, a stagehand slipped back into the darkened Ethel Barrymore Theatre to fetch some tools and found Marlon Brando alone under the single ghost-light, leaning over the edge of the stage and muttering his way through Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason.