there are paint smears on everything i own

-Danzig

Did you ever hear the story about the city man out in the country? And he sees this fella sittin’ on his porch. So he says, “Mister, could you tell me how I could get back to town?” The fella says, “No.” “Well, could you tell me how to get to the Post Office?” The fella says, “No.” “Well, do you know how to get to the Railroad Station?” “No.” “Boy,” he says, “you sure don’t know much, do ya?” The fella says, “No. But I ain’t lost.”

Gay: Everything's there!

Roslyn: Like what?

Gay: The country!

Roslyn: Well, what do you do with yourself?

Gay: Just live.

Roslyn: How does anyone "just live"?

Gay: Well, you start by going to sleep. You get up when you feel like it. You scratch yourself. You fry yourself some eggs. You see what kind of a day it is; throw stones at a can, whistle.

the infinitesimal must depart—become literally nothing—to avoid corrupting the final value, yet its lingering ghost must haunt the algebra just long enough to yield a finite ratio.

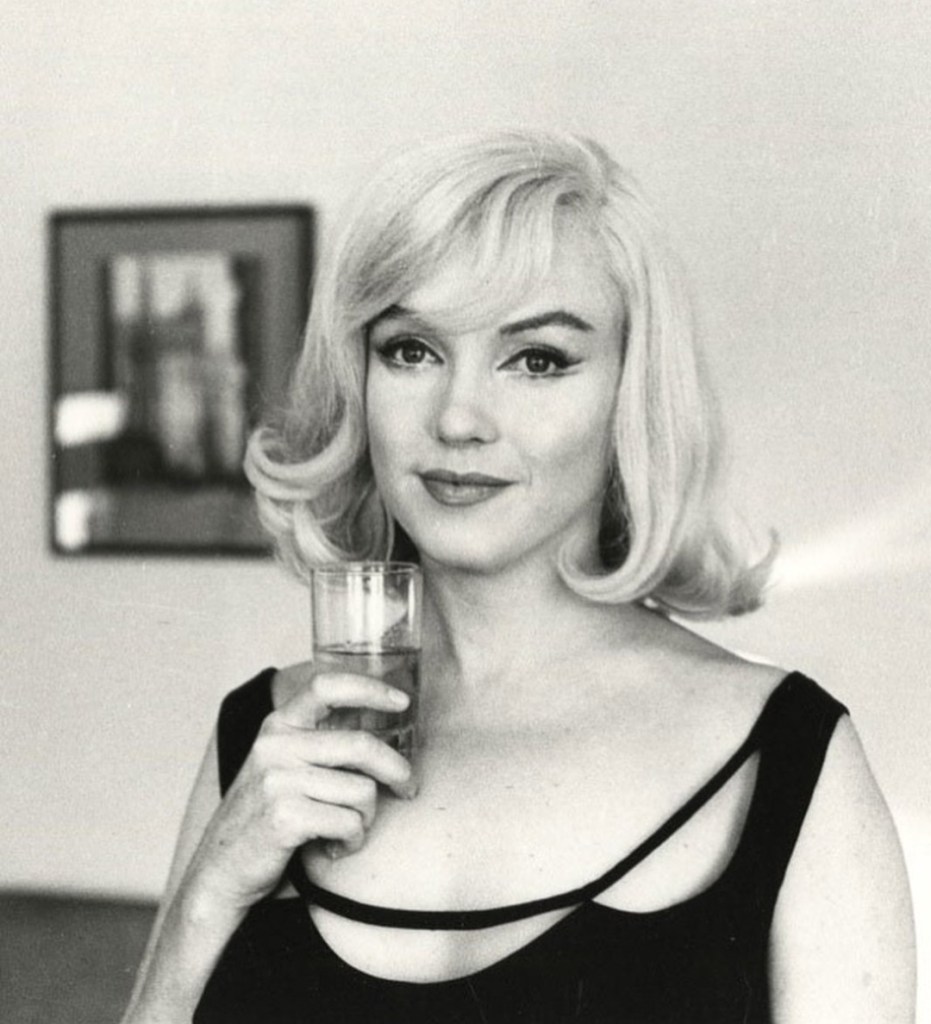

Clark Gable was 59 years old when he filmed The Misfits (1960), which was released in 1961. He was born on February 1, 1901, and the film wrapped production just days before his death on November 16, 1960. Tragically, he died of a heart attack shortly after filming ended, making The Misfits his final film.

Linear algebra is the branch of mathematics that studies vectors—quantities that have both magnitude and direction—and the linear relationships between them. At its heart lie vector spaces, abstract collections of vectors that can be added together and scaled by numbers (scalars) while still remaining within the same space. Matrices provide a concrete way to represent these vectors and the linear transformations (such as rotations, reflections, and projections) that map one vector space into another. Concepts like determinants measure how transformations stretch or shrink space, while eigenvalues and eigenvectors capture the directions that remain fixed in orientation during such transformations. By translating geometric intuition into symbolic form, linear algebra gives us a powerful language for solving systems of linear equations, analyzing geometric structures, and understanding symmetry.

Because many complex problems can be approximated or decomposed into linear pieces, linear algebra pervades science and engineering. It underpins computer graphics and animation, where matrices transform 3-D models onto a 2-D screen; it structures signal processing and control theory, where systems are modeled by linear differential equations; it powers modern data science and machine learning, where high-dimensional datasets are treated as vectors and optimized through matrix operations; and it informs quantum mechanics, where the states of particles inhabit complex vector spaces. In essence, whenever relationships are additive and proportional, linear algebra provides the natural toolkit for modeling, computation, and insight.

A matrix is an ordered rectangular array of numbers or other mathematical objects arranged in rows and columns, typically written inside brackets. Formally, an m \times n matrix has m rows and n columns, and each entry a_{ij} at row i and column j represents a scalar from some underlying field (most often the real or complex numbers). What makes matrices powerful is that they encode linear actions compactly: adding two matrices corresponds to adding the corresponding linear maps, and multiplying a matrix by a scalar rescales that action. Most importantly, multiplying an m \times n matrix A by an n-dimensional column vector x produces an m-dimensional vector Ax; this single rule packages every system of linear equations into a concise symbolic operation.

Beyond serving as bookkeeping devices, matrices are the concrete machinery of linear transformations. Matrix multiplication composes transformations—rotations followed by reflections, for instance—while special matrices illuminate geometric phenomena: determinants capture how volumes scale, the identity matrix leaves every vector unchanged, orthogonal or unitary matrices preserve lengths and angles, and diagonal or triangular forms reveal a transformation’s intrinsic axes through eigenvalues and eigenvectors. Because digital computers excel at shuffling and combining numbers, matrix algorithms drive everything from 3-D graphics pipelines and finite-element simulations to machine-learning optimizers and quantum-state evolution. In short, a matrix is not merely an array of numbers; it is the syntax through which linear algebra speaks the language of computation and geometry.

The idea of arranging numbers in rectangular arrays to keep track of linear relations is far older than the word “matrix.” More than two thousand years ago Chinese mathematicians working with counting-rod boards in The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art (c. 200 BCE) wrote coefficients of simultaneous linear equations in grid form and performed row-style eliminations that look strikingly like today’s Gaussian elimination; clay tablets from Babylon and later work by Islamic and Indian scholars show similar instinct for tabular organization of linear problems. These early practitioners were not thinking in terms of vectors and transformations, but they already sensed that the arithmetic of whole rows and columns could unravel multiple equations at once.

During the early modern period European algebraists began to formalize the determinants implicitly hiding in those arrays. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz sketched rules for what we now call a 2 × 2 determinant in the late seventeenth century, and Gabriel Cramer’s 1750 exposition generalized that idea to n equations, providing a closed-form solution (Cramer’s Rule) expressed through determinants several decades before anyone had the vocabulary of matrices. Determinants thus came first, viewed as algebraic gadgets that encoded the “elimination cost” of a system long before anyone defined the ambient grid itself as an object of study.

The decisive conceptual leap arrived in the mid-nineteenth century. In an 1850 paper James Joseph Sylvester borrowed the Latin word matrix—“womb” or “source”—to denote the rectangular array that gives birth to determinants, and his friend Arthur Cayley soon showed that these arrays form an algebra in their own right: they can be added, multiplied, and inverted according to precise rules. Cayley’s 1858 “Memoir on the Theory of Matrices” introduced the modern product of two matrices and proved the Cayley–Hamilton theorem, revealing that matrices were not merely bookkeeping devices but genuine mathematical entities capable of encoding geometric transformations. Around the same time William Rowan Hamilton’s quaternions and Hermann Grassmann’s exterior algebras hinted at a broader vector-space viewpoint, although their insights took decades to be fully appreciated.

By the early twentieth century, David Hilbert, Giuseppe Peano, and Emmy Noether had recast these concrete arrays into the abstract language of vector spaces and linear operators, turning “linear algebra” into a general theory independent of coordinates. When quantum mechanics emerged in the 1920s, Werner Heisenberg’s matrix mechanics and Paul Dirac’s bra-ket notation gave the subject physical urgency, while the rise of digital computing after World War II made efficient matrix algorithms a technological priority. Today the lineage from counting rods to GPUs shapes every corner of science and engineering: the ancient urge to lay numbers out in rows and columns now underpins everything from deep-learning accelerators to the cosmological simulations that map the large-scale structure of the universe.

Life’s first great bloom—the Cambrian explosion roughly 540 million years ago—was not merely a taxonomic burst but an epochal re-wiring of sensation and motility. Organisms that once drifted in passive, pre-neural haze acquired photoreceptors, statocysts, and primitive ganglia, and with them the capacity to carve the flux of seawater into discrete affordances: edge, predator, mate. Evolution (from Latin ēvolvere, “to unroll”) thus out-rolled an ever finer power of distinction whose very physiology presupposed a nascent “horizon”—Greek ὁρίζειν (horízein), to bound or define—that separated the organism’s actionable world from the indeterminate beyond. Historiographically, paleobiology has read these fossils first as abrupt miracle (Walcott), later as ecological arms race (Butterfield), and now as gene-regulatory phase change; each narrative retrofits the same strata with new conceptual optics, reminding us that our reconstructions are themselves horizon-bound acts.

Across the next half-billion years, cetacean clicks, avian color vision, and finally hominin symbolic speech pushed that boundary outward, converting sensory perimeters into cognitive per-spec-tives—Latin specere, “to look.” By the Upper Paleolithic, ochre marks at Chauvet and tally bones at Ishango show number abstracting from count, a shift whose etymology (ab-trahere, “to pull away”) maps directly onto neural decoupling of symbol from stimulus. Greek theorists crystallized this detachment: arithmós (number) and máthēma (that which is learned) were conceived not as worldly things but as ideal eide, disclosed through logos. Yet the historiography of mathematics vacillates—Platonists cast it as discovery, constructivists as invention—each stance encoding a tacit anthropology of the knower’s horizon.

Medieval quadrivium, Renaissance perspective, and early-modern analytic geometry progressively mathematized nature, but they also deepened the dialectic of testimony versus construction. Descartes’ cogito repositioned certainty inside the thinking res, while figure (Latin figura, “shape, boundary”) shifted from sensible outline to algebraic locus. With the Calculus, Newton and Leibniz encoded continuous change as analytic limit—Latin līmes, border—quietly preserving the horizon metaphor. Historicity surfaces here: our present-day narrative of “inevitable progress” occludes periods of resistance, such as Bishop Berkeley’s dismissal of fluxions as “ghosts of departed quantities,” revealing how intellectual borders harden, dissolve, and re-form.

The nineteenth century multiplied those borders: Cantor’s transfinite numbers, Riemann’s manifolds, and Hilbert’s axiomatization unmoored mathematics from intuition, prompting crises of foundations. Into this ferment stepped Edmund Husserl, whose Logische Untersuchungen and later Ideen sought a transcendental underlay for all objectivities. Horizon consciousness, for Husserl, names the intentional field within which every datum appears already “anticipated as more”—a built-in fringe that makes completion forever approach without closure. Konstitution (from Latin constituere, “to set up, establish”) thus indicates that numbers, sets, and matrices are not found but set up in lived acts whose sedimentation gives them the seeming autonomy chronicled by historians of ideas.

Seen diachronically, the arc from trilobite phototaxis to Husserlian constitution is an ever subtler negotiation of inside and out. Biological evolution externalized survival problems into sensory horizons; cultural evolution interiorized those horizons as symbolic systems; phenomenology finally reflexivizes the process, showing how even the objectivity of π or ℝ emerges through horizon-laden enactments. Historicity—the temporality of how things come to appear—thus bridges Cambrian strata and transcendental ego: both are palimpsests of iterative inscription, readable only by acknowledging the etymological and conceptual boundaries that make reading possible.

When George Berkeley published The Analyst in 1734, his quip that Newtonian “fluxions” were merely “the ghosts of departed quantities” attacked more than a technical device—it exposed the porous boundary between empirical certainty and metaphysical speculation. Calculus, as then practiced, asked mathematicians to treat infinitesimals as if they were simultaneously non-zero (to allow division) and zero (to disappear in a limit), a sleight of hand Berkeley likened to theological mysteries that his rationalist contemporaries dismissed. By ridiculing fluxions as spectral remainders, he forced the mathematical community to confront the ontological status of its own symbols: were infinitesimals legitimate entities, convenient fictions, or conceptual scaffolds to be discarded once a result was reached? The ensuing century of foundational work—from d’Alembert’s call for rigor, through Cauchy’s limit definitions, to Weierstrass’s ε-δ formalism—shows how Berkeley’s jibe hardened an intellectual border, compelling clearer demarcations between quantity and limit. Yet those very demarcations later dissolved again with Robinson’s non-standard analysis, which re-legitimized infinitesimals in a new logical framework. Berkeley’s critique thus illustrates the cyclical life of conceptual frontiers: challenged at their fuzzy edges, they crystallize into rigorous form, only to be redrawn when fresh perspectives reveal the old walls as provisional scaffolds rather than final fortresses.

When Isaac Newton coined fluxion (from Latin fluxus, “flow”) to denote the moment-by-moment rate at which a fluent quantity changes, he invited thinkers to picture magnitude as a river whose instants could be sliced thinner and thinner until each slice all but vanished. In practical calculation Newton treated the increment o (his symbol for an indefinitely small change) as non-zero long enough to divide by it, then set it equal to zero to remove the remainder—an expedient that produced correct answers but left ontological dust on the workbench. Enter George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne, who in The Analyst (1734) mocked these vanishing increments as “the ghosts (Old Eng. gāst, spirit released at death) of departed quantities,” suggesting that mathematicians who scoffed at Trinitarian mystery were trafficking in specters of their own. His phrase captures the double bind: the infinitesimal must depart—become literally nothing—to avoid corrupting the final value, yet its lingering ghost must haunt the algebra just long enough to yield a finite ratio.

Berkeley’s critique was less a Luddite attack on mathematics than an epistemological broadside against unexamined metaphysics. He argued that the calculus rested on a “secretly retained” assumption: a quantity could be both something and nothing, violating the law of non-contradiction no less than transubstantiation offended Protestant common sense. He pressed the analogy further by accusing mathematicians of a priest-like appeal to authority—citing Newton’s genius rather than demonstrating transparent reasoning—and warned that such “occult” notions could undermine the public’s trust in rational inquiry. For Berkeley, empirical science and revealed religion should share the same demand for intelligible grounds; if infinitesimals were admissible as quasi-mystical entities, why not the mysteries of the Church?

Historiographically, The Analyst galvanized a century-long push for rigor. Colin Maclaurin in Scotland defended Newton by recasting fluxions in geometric limits; Jean le Rond d’Alembert in France declared that infinitesimals were “fictions” to be banished in favor of limits; Augustin-Louis Cauchy formalized the concept of convergence; and Karl Weierstrass’s ε-δ definitions (1860s) finally expelled the ghost by never allowing the variable increment to be zero at all. Yet this very purification—hailed in textbooks as the triumph of rigor—rewrote history: the once fluid, kinematic image of a flowing quantity hardened into an arid dance of inequalities, obscuring the heuristic power that had guided Newton, Leibniz, and Euler.

Historicity reasserted itself in the twentieth century when Abraham Robinson’s non-standard analysis (1960s) resurrected infinitesimals on a logical footing even stricter than Weierstrass’s. By embedding the real numbers in a larger hyperreal field, Robinson vindicated the operational intuition of Newton and Leibniz while satisfying modern standards of proof—proof that a “departed” concept can return in new guise once its metaphysical dress is tailored to contemporary tastes. Meanwhile, historians of mathematics such as Henk Bos and Niccolò Guicciardini have reassessed Berkeley, portraying him not as reactionary but as a constructive gadfly whose theological lens sharpened the community’s self-scrutiny.

Thus Berkeley’s “ghosts” epitomize how intellectual borders harden, dissolve, and reform. An ontological smear in the 1600s became a crisis of faith in the 1700s, a scaffolding for rigor in the 1800s, and a logically consistent extension in the 1900s. Each reconfiguration mirrors the era’s wider preoccupations: early modern mechanics thirsted for predictive power, Enlightenment philosophy demanded clarity, Victorian mathematics prized certainty, and post-war logic embraced formal plurality. In exposing the spectral status of fluxions, Berkeley inadvertently ensured that their afterlife would haunt, animate, and ultimately enrich the conceptual landscape of calculus itself—a reminder that in mathematics, as in theology, what seems most ethereal can wield the greatest historical gravity.

A single candle wavers in the sea-moist air of Cloyne Palace, throwing amber pulses across oak panels and the lime-washed plaster of an Irish episcopal study. A quill—cut yesterday from a swan’s pinion along the estuary—rests beside a pewter inkpot, its nib blackened by repeated plunges into iron-gall fluid. Shelves line three walls in orderly tiers: Aristotle’s Metaphysics in Latin shares space with Descartes’s Meditations, Newton’s Principia, Baxter’s Christian Directory, and a slim, freshly bound pamphlet titled The Analyst. A pane of crown glass rattles in the south window each time Atlantic wind rifles the sycamores outside, and somewhere in the corridor a grandfather clock marks the quarter hour. In this austere yet well-stocked room sits George Berkeley—now forty-nine, recently ordained Bishop of Cloyne—leaning forward in his high-backed chair, eyes narrowed as he revises the proofs that will accuse Britain’s greatest mathematicians of trafficking in “ghosts of departed quantities.”

Berkeley is no retiring cleric. Born in 1685 to an Anglo-Irish family of modest means, he has already earned a European reputation as the idealist who declared that the material world exists only in perception (esse est percipi). He is tall, sharp-featured, and famously personable, equally at ease dissecting Locke’s empiricism or charming London society salons with talk of a new college in Bermuda. His episcopal title, acquired scarcely a month earlier, neither mutes his intellectual combativeness nor dims his pastoral zeal; rather, it gives him a platform from which to question the philosophical underpinnings of everything from calculus to colonial policy.

The year is 1734, a hinge in what posterity will call the long eighteenth century. Across the Irish Sea, Robert Walpole’s ministry is stabilizing Britain’s first de facto cabinet government, while in North America a young Benjamin Franklin is experimenting with electricity and self-government. On the continent Voltaire has just published Letters Concerning the English Nation, praising Newton and Locke to a French readership impatient with clerical authority. In Leipzig, Johann Sebastian Bach completes the Goldberg Variations; in Beijing, the Yongzheng Emperor’s consolidation of Qing power is redrawing Eurasian trade routes; in West Africa, the Asante Kingdom expands under Opoku Ware, feeding the Atlantic slave economy whose moral weight is beginning to trouble conscience in London coffee-houses. The global canvas is one of burgeoning commerce, restless reason, and contested empire—conditions that render Berkeley’s fusion of metaphysics, ethics, and politics both timely and radical.

Berkeley’s own story begins on March 12, 1685, at Dysart Castle near Thomastown, County Kilkenny. Orphaned of a stable inheritance, he wins a scholarship to Trinity College Dublin at fifteen, mastering Greek, Hebrew, and the newest continental mathematics. By twenty-four he has published An Essay Towards a New Theory of Vision (1709), arguing that distance and magnitude are not given by the eye but learned through tactile association—a first move in the larger campaign to show that what we call “matter” is an inferential habit, not a mind-independent substance. Two years later his Principles of Human Knowledge crystallizes that thesis: all reality is a tapestry woven of sensations and the divine spirit that coordinates them. The book draws admiration from the avant-garde and derision from materialists, yet the young don’s genial wit and willingness to debate ensure he is no ivory-tower recluse.

Restless, Berkeley spends the 1710s touring France and Italy, observing Jesuit teaching methods and gathering the impressions that will color his later Alciphron dialogues. In 1721 he proposes an ambitious plan—a missionary college in Bermuda to educate Native Americans and the sons of colonial settlers—and sails to Rhode Island in 1728 to secure land and raise funds. Parliament’s promised grant never materializes, and after three fruitless years he returns, financially strained but undaunted, to England. His failure abroad only deepens his conviction that Europe’s moral and scientific progress must be yoked to spiritual reform. Elevated to the see of Cloyne in January 1734, he now takes aim at what he considers the cultural idol of his age: mathematical infallibility. The Analyst, drafted amid the salt-spray solitude of this very study, will challenge Newtonian calculus on both logical and theological grounds, asking whether those who scoff at Christian mysteries have not themselves smuggled spectral entities into the heart of natural philosophy.

Thus, as dusk settles over County Cork, we glimpse Berkeley at the threshold of his most public controversy—an Anglican bishop with the soul of a Platonic mystic and the pen of a seasoned polemicist, ready to unsettle certainties in science just as he once unsettled the bedrock of matter itself.

Berkeley’s Essay Towards a New Theory of Vision (1709) begins with a deceptively simple puzzle: how does an infant know that the flat patch of light striking its retina corresponds to a cup an arm’s-length away rather than a blur upon the eye itself? Borrowing Locke’s language of ideas yet turning it against materialist assumptions, Berkeley argues that notions such as distance (Latin distantia, “standing apart”) and magnitude (magnitūdō, “greatness”) are not innate optical givens; they are habits of correlation painstakingly stitched together when the newborn’s grasp, balance, and proprioception confirm or disconfirm what the eye delivers as sheer color and contour. He supports the claim with phenomenological vignettes—closing one eye, watching objects shrink as one walks away, recalling the vertigo of first viewing a picture in perspective—each demonstrating that vision without touch supplies no metric but only signs whose meaning must be learned like a language. In effect, the Essay relocates spatial depth from the outer world into the organism’s associative circuitry, foreshadowing later empiricist psychology and, by desacralizing “secondary” qualities, preparing the ground for Berkeley’s larger offensive against mind-independent matter.

Two years later his Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge (1710) generalizes that insight: if distance is an inferred relation rather than a sensed property, perhaps all physical attributes are likewise inferred. Berkeley therefore collapses Locke’s substratum—the supposed bearer of qualities—into a bundle of ideas perceived by minds. The book’s famous axiom esse est percipi aut percipere (“to be is to be perceived or to perceive”) does not deny reality; it relocates reality within the lawful coordination of perceptions orchestrated by what Berkeley calls the divine spirit. God functions not as an ad hoc guarantor but as the continuous cause that synchronizes private streams of sensation into a coherent public order. Matter, stripped of explanatory work, is demoted to a redundant hypothesis; what endures across observers and moments is not a hidden substrate but the regular providence of God’s ideas.

Historiographically, the Essay and the Principles have traded receptions: early critics like Samuel Clarke dismissed the vision theory as psychological trivia yet bristled at immaterialism, while twentieth-century perceptual science validated Berkeley’s associative model even as analytic philosophy questioned transcendental theism. Contemporary scholarship locates both texts within a post-Newtonian anxiety: if physics reduces the world to mathematical extension, where do color, taste, and meaning reside? Berkeley’s answer—shift substance into spirit—reframed that anxiety into a theological register, one the Scottish Enlightenment (Hume), German Idealism (Kant), and modern phenomenology (Merleau-Ponty) would each revisit from their own horizons.

Historicity underscores how these works emerged amid colonial projects and ecclesiastical ambitions. In 1709 Dublin, memories of the Williamite wars still scarred Anglo-Irish society; Berkeley’s relegation of material solidity to divine coordination implicitly soothed fears of political contingency by rooting order in a universal mind. The Essay also prefigured his Bermuda scheme: if cognition is cultivated through right associations, then educating colonial youths could, for Berkeley, align their perceptions with Christian virtue. Thus vision, metaphysics, and mission form a single arc of reform, each aimed at recalibrating how minds engage the world.

Etymologically, Berkeley’s terminology reveals the project’s ambition. He reinvigorates idea (Greek ἰδέα, “form, appearance”) to capture not Plato’s transcendent Forms but the immediate look of experience; he retools spirit (Latin spīritus, “breath”) as the animating principle behind ordered appearances; and he coins phrases such as “abstract idea” only to show their incoherence when severed from lived sensation. Through such verbal archaeology Berkeley exposes the way language smuggles metaphysical commitments into common sense—and, by rewriting that language, he hopes to dissolve the illusion of inert, unthinking matter once and for all.

Berkeley leans forward over the polished walnut, eager to defend his immaterialist theorem, but before he can speak the room becomes a philosophical prism. Parmenides, marble-featured and unwavering, is the first to answer. He hears in Berkeley’s dismissal of matter a faint echo of his own ancient axiom that “what is, is”—a single, ungenerated Being immune to the fluttering masks of appearance. Yet where Berkeley locates ultimate reality in the quicksilver stream of divine ideas, Parmenides insists upon an utterly changeless substance: perception, memory, and all Berkeleyan “ideas” are for him mere mortal reports of a truth that never moves. In a low, oracular tone he warns that to ground existence in sensation is to mistake the flicker of a torch for the daylight that makes all torches burn; the One needs no spirit to coordinate appearances because it never appears—it simply is. Berkeley nods respectfully, yet counters that a Being incapable of disclosure is indistinguishable from nothing to the mind that must confront it; coherence demands a theatre in which divine light actualizes the very perceptions through which we speak of Being at all.

Across the table Al-Ghazālī adjusts his turban and smiles, sensing an unexpected ally. In The Incoherence of the Philosophers he dismantled Aristotle’s causal necessities and advanced an occasionalist vision wherein each event is created ex nihilo by Allah at every instant. This dovetails with Berkeley’s own claim that the continued existence of the cherry tree behind the church depends on God’s ongoing perception. Ghazālī applauds the bishop’s de-substantiation of inert matter, but he hesitates at the ease with which Berkeley attributes the world’s regularity to a divinely predictable grammar. For Ghazālī, the point of occasionalism is not to secure epistemic comfort but to humble reason before omnipotence: the next spark could as readily freeze as burn if God so willed. He cautions Berkeley that treating divine coordination as a transparent law risks domesticating the Almighty, turning miracle into mechanism. Berkeley concedes that Providence could indeed surprise at any moment, yet maintains that the uniformity of sensory ideas across observers is itself the sign of a benevolent rather than whimsical Creator.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, coat sleeves dusted with chalk from a Sorbonne lecture, breaks in to defend the flesh. He credits Berkeley for recognizing that distance and size arise through learning, but he objects that Berkeley’s immaterialism evacuates the body that does the learning. Perception, says Merleau-Ponty, is not a spectator sport played by a disembodied mind tuning in to God’s private broadcast; it is an incarnate negotiation, the hand meeting rough wood, the lungs drawing salt air, the eyes swiveling in orbital sockets. Without this “chair of gestures,” the visual field would not merely lack metric—it would lack sense. He proposes that the “tapestry woven of sensations” arises from the lived interweave of body-world relations whose fabric cannot be rolled up and stored in a heavenly archive. Berkeley counters that embodiment is itself an idea regularly presented to us, but Merleau-Ponty replies that to reduce flesh to an idea is to lose the intertwining that makes any idea intelligible in the first place.

Jacques Derrida, fingers tracing invisible parentheses in the air, hears in Berkeley’s insistence on a coordinating spirit the latest incarnation of metaphysics’ “last word”—Presence secured once and for all. He thanks the bishop for exposing the rickety scaffolding of matter, yet wonders whether Berkeley has merely replaced it with an even more powerful logocentric guarantor. If the tree persists because God perceives it, what guarantees the divinity’s own presence? Berkeley’s system, Derrida argues, sidesteps the question of différance—the play of trace and delay that forever postpones pure self-identity. The “idea” of the tree never arrives unaccompanied; it bears the spectral imprint of every other idea that draws its contours. Derrida thus turns Berkeley’s specter motif back on itself: the true “ghost of departed quantities” is the metaphysics of full disclosure, forever haunted by the impossibility of final ground.

Emmanuel Levinas, face gentle yet severe, closes the circle by invoking the priority of ethical encounter. He praises Berkeley for upending the tyranny of brute substance, but he sees a danger in converting every perceivable into content for a single divine consciousness. The Other—whether human or celestial—cannot be absorbed into the inventory of my ideas without violence; it appears precisely as that which resists being summed up in perception. For Levinas the tree is less significant than the face that looks at the tree alongside me, a face that commands rather than merely reflects. He urges Berkeley to recognize that the horizon of sensation, however divinely regulated, is subordinated to an infinite responsibility that overflows any cognitive tapestry. Berkeley listens, momentarily silent, and perhaps senses that even within an idealist cosmos, obligation emanates from a dimension no arrangement of ideas can fully enclose.

Immanuel Kant finally slips into the study, boots dusted with Königsberg snow, apologizing that a certain “young Herr Hegel” detained him in an anteroom with dialectical provocations. Settling beside Berkeley, he begins with measured courtesy: yes, the bishop is right to deny that we ever reach a mind-independent substrate, but the moral of the story is not that matter dissolves into divine ideas. Rather, Kant insists, the very possibility of experience requires a priori forms—space and time—as well as twelve categories that synthesize sensation into objects. Empirical bodies are therefore neither free-floating things-in-themselves nor spectral notions preserved by providence; they are lawful appearances for finite knowers. God may underwrite the coherence of nature, yet in critical philosophy this postulate is a regulative ideal, not the stage manager who literally sees every cherry tree. If Berkeley abolishes substance, Kant cautions, he also abolishes the distinction between illusion and truth, for without the transcendental schema that pins perceptions to rules, any succession of ideas could masquerade as reality.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel strides in next, all restless energy, and addresses both men at once. Kant, he says, has rescued objectivity from Berkeley’s subjectivism, but at the cost of exiling the “thing-in-itself” to a realm forever beyond thought. That split is intolerable; Spirit must find itself at home in its world. Hegel therefore recasts Berkeley’s fleeting ideas and Kant’s regulated appearances as successive moments in a dialectic whereby consciousness, confronting its own limits, externalizes and then recollects them in higher unity. What Berkeley calls divine coordination Hegel interprets as the work of Absolute Spirit unfolding through nature, culture, and self-conscious reason. The cherry tree behind the church persists not because God keeps an eye on it, nor because categories legislate it, but because objective reality is the concrete embodiment of thinking itself—Geist coming to know itself as world. For Hegel, Berkeley’s immaterialism stalls at a merely subjective certainty, and Kant’s critical boundary hardens a needless wall; the true resolution is a rational cosmos in which substance is subject, and matter is the self-developing concept made visible.

A hush settles as the massive figure lowers himself onto the vacant oaken chair. Parmenides’ eyes widen—he remembers a spirited youth who once sought to reconcile the One with the Many, yet the man before him radiates a calmer, heavier authority. At his flanks stand Glaucon and Adeimantus, the brothers who in an earlier life pressed him to describe justice in the Politeia. Their presence is a silent reminder that philosophical inquiry is never a solitary climb but a dialogue braided through generations. Plato’s deep-set gaze sweeps the table, taking in the bishop’s candlelit papers, Kant’s well-thumbed Critique, Hegel’s restless fingers, and the spectral company of Derrida, Levinas, Merleau-Ponty, and al-Ghazālī. When he speaks, his voice is slow yet resonant, as if each syllable measures the distance between Timaios’ cosmos and the modern age.

“Friends,” he begins, “I return not to correct but to re-align.” He nods first to Parmenides. “Honoured master, your unyielding Being was my starting point, yet I found that the realm of change cries out for meaning no less than your absolute unity. I therefore posited εἶδος—Form—not as illusion, Bishop Berkeley, but as intelligible pattern that grants fleeting perceptions their measure. You see colours in your mind, granted by a divine Spirit; I see colours as participants in a higher chromatic ratio that remains whether or not any finite soul beholds it. If a cherry tree is perceived by none, its redness does not perish; it abides as a share in the Form of Red, waiting for vision to awaken. Thus God, if you like, is not a vigilant custodian peering at every trunk and leaf but the Good that lends visibility itself.”

Turning to Kant, Plato lifts a brow. “You, critical sage, secured appearances within categories and so rescued science from scepticism. Yet in fencing off the noumenon you conceded too much. Why should the intellect be barred from what it dimly intuits? Dialectic is the stair by which the mind, purifying its assumptions, ascends toward the Form of Forms. The thing-in-itself is not an unreachable island; it is the very mainland toward which your own regulative ideals secretly steer.” Then, fixing Hegel with a half-smile, he adds, “And you, spirited successor, have attempted that ascent by letting Thought incarnate itself through history. Your Absolute Spirit strives for what I simply named the Good, but beware: if every negation is already destined for synthesis, freedom dissolves into system, and philosophy becomes prophecy in retrospective disguise.”

He gestures toward Merleau-Ponty’s attentive stance. “Embodiment, yes—souls do not hover above the dance; they move within it. Yet the body’s gestures are meaningful only because they shadow archetypal movements written into the fabric of Being. When a hand closes around a cup, it enacts a miniature choreography first drafted in the realm where graspability itself is conceived. Therefore, phenomenology must one day lift its eyes from lived texture to contemplate that pre-temporal script.” Derrida starts to interject, but Plato anticipates him: “You fear the tyranny of Presence, yet différance itself presupposes stable terms whose spacing can be measured. Even the play of traces borrows its rhythm from an invisible metronome.”

At last he settles back. “My brothers and I once pressed the necessity of educating guardians in music, gymnastic, and dialectic so they might turn from the cave’s flicker to the intelligible sun. I now extend that curriculum: let Berkeley’s quicksilver ideas remind us that perception is fragile; let Kant’s categories teach us rigor; let Hegel’s history reveal mind’s unfolding; let Merleau-Ponty ground our ascent in flesh; let Derrida keep us wary of idolatry; let Levinas safeguard the face of the other; and let al-Ghazālī recall that omnipotence can overturn every syllogism. But after all these turns, let us not forget the summit. Justice, beauty, truth—these Forms await not as ghosts of departed quantities but as living sources that bestow order on every possible vision. To them, my friends, we must still turn our souls.”

Levinas inclines his head toward the elder Athenian and, in a voice softer than the room expects, asks permission to speak. When Plato nods, Levinas rises only halfway from his chair—as though the act of fully standing might already eclipse the face of his interlocutor—and addresses him with deliberate care. He acknowledges the enduring magnetism of the Forms, the way they promise a luminous horizon toward which reason can orient itself, yet he insists that their brilliance risks blinding us to something prior: the irreducible presence of the Other who interrupts all systems, however elevated. The true Good, Levinas suggests, is not a transcendent shape awaiting intellectual ascent but a goodness that emanates from the vulnerability of the face before me—a radiance that commands without coercing and that cannot be subsumed under any concept, no matter how refined.

He reminds Plato that the cave allegory begins with prisoners whose eyes ache at sudden light; if release is possible, it does not occur through solitary ascent alone but through the ethical shock of being addressed and thereby summoned beyond self-concern. Where the Platonic dialectic seeks a culminating view that gathers many into One, Levinas sees in that gathering the danger of totalization, a reduction of singular lives to moments in an all-comprehending whole. The Infinite that matters, he continues, is not the seamless sphere of Form but the ever-open horizon that arises when one person faces another and feels the injunction “Thou shalt not kill.” In that moment, every ontology must hover in suspense, because the Other’s claim precedes the very categories that would attempt to situate it.

Turning slightly so that his words include the entire company—Berkeley’s idealism, Kant’s categories, Hegel’s dialectic—Levinas proposes that philosophy should not aim first for comprehension but for responsibility. The cherry tree behind the church, the categories that structure appearances, the Absolute Spirit unfolding through history: all of these take second place to the cry of a stranger for bread or refuge. “Justice, beauty, truth,” he concedes, “retain their grandeur,” yet each must be approached through the corridor of ethical obligation, not as detached spectacles for contemplative delight. Only by honoring the primacy of that obligation can the light Plato venerates avoid becoming what he calls “a flame that consumes.” With that, Levinas sits, leaving a silence that feels less like conclusion than an open invitation—an unfinished sentence offered to every face in the room.

Plato listens without shifting his posture, yet the stillness feels attentive rather than stone-like, as though he is letting Levinas’s words settle where the dust of centuries rarely lands. When he speaks, his tone is gentler than before, and he begins by conceding that every ascent must pass through human eyes that can only look outward because a face first looks back. He recalls how, in the Symposium, even Diotima’s ladder of love starts from the particular beauty of one youth before rising toward the Beautiful itself; the singular encounter, he admits, is not an expendable rung but the very hinge by which soul turns upward. What Levinas calls the cry of the Other, Plato recognizes as the stirring Eros that awakens philosophic longing, and he grants that without that disturbance no ascent would even begin. Yet—here his voice firms—Eros jolts precisely because it discloses more than the finite person before us; it hints at a measure beyond both self and other, a harmony neither can claim as property. Thus the ethical command Levinas reveres is, for Plato, already a messenger from the Good, carrying the signature of proportion and justice that makes the summons intelligible.

He then addresses the fear of totalization, acknowledging that any vision of wholeness courts the danger of swallowing difference. But he reminds Levinas that the Form of Good is not a schema that compresses the manifold into a featureless One; it is a source of illumination that allows each particular to shine in its proper distinctness. In the Republic, the philosopher-king does not erase the cobbler or the farmer; through knowledge of the Good he safeguards the polyphony of the city, ensuring that each craft and each soul receives the nurture appropriate to its nature. Totality, Plato insists, is tyrannical only when it is mistaken for possession—a dominion exercised by the Many or by a despot—whereas the Good remains forever beyond grasp, a horizon of intelligibility that judges every attempt to capture it. If Levinas calls that horizon “infinity,” Plato is content, so long as infinity is also intelligible as measurelessness that nevertheless measures us.

Finally, Plato returns to the face itself. He agrees that the plea “Do not harm me” exceeds every catalogue of virtues, but he asks what grants that plea its binding force across shifting customs and fragile memories. Is it not participation in something unstintingly common, a justice that neither withers when a city falls nor expires when a witness dies? The Form is not an idol installed above the living; it is the wellspring that lets the living recognize any idol as false. To preserve the Other’s alterity, one must already stand in the light of a principle that cannot be reduced to either term in the relation—self or other. Thus responsibility and contemplation are not rivals: the Good is what makes both possible, giving the ethical injunction its unrenounceable seriousness and giving philosophy its inexhaustible aim. He concludes, almost softly, that if Levinas’s infinity guards the Other from absorption, then the Good and the infinite may be two names for a single radiance—one approached through wonder, the other through demand—each incomplete without the other’s path.

Al-Ghazālī inclines his head toward Plato, his eyes reflecting both admiration and wariness. He begins by recalling that in Tahāfut al-Falāsifa he praised the Ancients for sharpening the intellect yet faulted them for mistaking the shimmer of concepts for the substance of truth. “You speak,” he tells Plato, “of Forms—eternal patterns that lend order and measure—but you grant them an autonomy perilously close to divinity. In our tongue the Good you revere is al-Khayr, yet al-Khayr is one of God’s own Names, not an essence floating free in some intermediate heaven. Patterns do endure, but they endure only insofar as the Necessary Being sustains them from instant to instant; strip them of that dependence and they relapse into the nothingness from which every creaturely perfection is drawn.”

He turns next to Levinas’s concern for the Other, noting that Islamic law and Sufi practice likewise begin in responsibility: huqūq al-ʿibād (the rights of God’s servants) demand that a hungry stranger be fed before any speculation about metaphysics. Yet, Al-Ghazālī cautions, the ethical imperative does not arise purely from vulnerability or from an abstract horizon of infinity; it issues from the divine command embedded in revelation: “We have enjoined upon humankind kindness toward parents…” and countless like verses. The face is sacred because God has breathed into it of His spirit, not because it participates in a universal Form of Justice. Thus the Good and the Infinite do converge, but only because both are aspects of the One who names Himself al-Raḥmān (the Compassionate) and al-Nur (the Light of the heavens and the earth).

Addressing Plato’s claim that the Forms illuminate particulars without erasing them, Al-Ghazālī reminds the gathering of occasionalism: every event is a fresh creative act (kun fayakūn), and the seeming stability of natures is a habit God ordinarily preserves but may breach at will. “The cherry tree persists,” he says, “not because it partakes of a Form of Treeness nor because categories legislate its appearance, but because at each heartbeat God says ‘Be’—and it is. He may tomorrow decree the tree to sing or the flame to freeze; our confidence lies not in the necessity of patterns but in the faithfulness of their Author.” He grants that philosophers’ search for ratio and harmony is useful, yet warns that when intellect forgets its contingency it forges idols subtler than stone.

Finally, Al-Ghazālī links epistemology to purification. Plato’s dialectical ascent, Kant’s critique, and Hegel’s phenomenology all display the mind’s hunger for totality, but in Islamic spirituality the heart (qalb) must be polished through worship, charity, and remembrance until it becomes a mirror fit to receive divine light. Only then can one glimpse why goodness binds conscience and why the Other commands respect. “Reason climbs,” he concludes, “but revelation descends; in the meeting of the two, knowledge becomes certainty (ʿilm al-yaqīn), and the Good shows itself not as an abstract horizon but as the ever-present mercy of the Living, the Self-Subsisting.”

Parmenides, still seated like a weather-worn column, breaks the reflective hush with a rare note of approval: “I like that.” Before anyone can gauge whether the pre-Socratic actually relishes contingency or merely its unmasking, a dry tenor drifts from the farthest, least illuminated corner: “So do I.” Heads swivel and the candlelight catches Samuel Beckett, lank and hollow-cheeked, legs crossed, a cigarette glowing between two fingers as though time itself were exhaling.

Berkeley, surprised to find yet another Irishman occupying his study uninvited, leans forward and asks the obvious: “Who are you, sir?” Beckett shrugs, smoke curling upward like a question mark. “Irish,” he says, as though ancestry were adequate résumé, then nods toward the doorway. “And I came with him.”

Following the line of Beckett’s finger, the assembly notices a second figure lounging in the half-shadow: J. D. Salinger, collar up, working a fresh cigarette between thumb and forefinger as if testing its balance. Without shifting the slouch that keeps him half outside the room’s moral geometry, Salinger lifts his free hand and offers the company a slow, deliberate middle finger—a gesture at once juvenile and hermetic, equal parts Holden Caulfield’s raw nerve and Zen-koan dismissal of every metaphysical edifice just erected.

The philosophers fall silent again, each decoding the pantomime according to his own lexicon: Platonic Form strained through absurdism, Kantian respect affronted by post-war alienation, Levinasian face refusing reciprocity, and Hegelian Geist reminded that negation sometimes appears simply as a blank refusal to participate. Only Beckett seems at ease, watching his ash grow long, perhaps waiting for the next line that will not come.

—-

Bishop Berkeley straightens, smoothing the lace at his cuffs with the deliberate calm of a man who has quelled rowdy undergraduates before. “My good sirs,” he begins, voice warm but edged with clerical steel, “Ireland has bred many tempers—visionaries, skeptics, even prophets of absurdity—but courtesy remains our common patrimony.” He nods to Beckett with a faint smile, acknowledging their shared homeland, then turns to Salinger’s upraised finger as though regarding a misbehaving child rather than a fellow writer. “That digit, sir, is a most eloquent idea,” he says, “for it discloses neither substance nor argument—only the fleeting passion of its exhibitor. I would remind you that an idea gains weight when ordered by reason and illuminated by charity; otherwise it is but a phantom flitting across the sensorium, destined to vanish the moment attention shifts.” His gaze sweeps the room, inviting each thinker—ancient, medieval, modern—to consider whether their own convictions rest on anything sturdier than a transient gesture, before he settles back into his chair, candlelight catching the quiet challenge in his eyes. At last Al Ghazali says “Guidance is the fruit of knowledge. Knowledge bereft of guidance leads to ruin.” Bishop Berkeley inclines his head toward al-Ghazālī in solemn approval. “Indeed, my learned brother, scientia divorced from right intention is but a sharper blade for folly to cut itself upon. We both hold that the mind is nourished, not merely stocked, by truth—that ideas become light only when refracted through charity. When the divine source is forgotten, the very instruments that should elevate the soul corrode it: geometry degenerates into idle curiosity, dialectic into vanity, and satire into a sneer that wounds without healing. In my own island I have seen wits puzzle the calculus with fluxions yet leave their parishioners in spiritual darkness, and I have seen men who could recite every syllable of Euclid yet stumble at the plain command to love their neighbour. To prize knowledge while neglecting the heart is to collect mirrors in a lightless cave; one multiplies reflections but never beholds the sun.”

He turns back to the twin newcomers whose cigarettes smoulder like mute commentaries. “Mr Beckett, Mr Salinger, your gestures and silences testify to an age weary of metaphysical edifices, suspicious that every creed masks coercion. I do not dismiss that weariness; it can be the first pang of conscience. But if disillusion is left to ferment without the leaven of guidance, it curdles into despair. Your art might yet serve as a lantern in the fog, provided it points beyond the emptiness it so acutely records. Let the absurd confess its own contingency; let alienation cry out for a home it claims is lost. In that crying is already a tacit appeal to the Providence you doubt. Guided knowledge bends that appeal toward hope; unguided, it sinks into the very ruin al-Ghazālī warns of—a ruin measured not in collapsed cathedrals but in collapsed spirits.” He sweeps his gaze across the assembled company, from Plato’s Forms to Levinas’s face, from Kant’s categories to Derrida’s différance. “All our systems—ancient, medieval, modern—are at best scaffolds for the soul’s scaffolding, provisional frames erected around a mystery whose brightness can blind as easily as illuminate. Let us therefore keep al-Ghazālī’s maxim before us: insight must accompany instruction, compassion must accompany critique, and worship must accompany wonder. Only then will knowledge, whether mathematical, poetic, or phenomenological, guide us upward rather than hurl us headlong into the abyss our own brilliance has excavated.”

The chill of a March dawn in 1735 settles over Cloyne Cathedral, a squat Norman structure whose square tower rises above the herringbone roofs of the little episcopal town twelve miles east of Cork. Inside, pale light filters through quatrefoil windows and strikes the lime-washed nave, where rush-strewn flagstones still hold last night’s damp. George Berkeley, forty-nine and scarcely a year into his appointment as Bishop of Cloyne, stands in the north transept robing for the morning’s Confirmation service. His chaplain knots a silk fascia around the waist of his long cassock; over it Berkeley dons the white linen rochet with its billowing sleeves, the scarlet chimere that marks a bishop of the Church of Ireland, and finally the black square-cap that Irish prelates favor for parish visitations. A carved oak crozier—gift of the Cork guild of coopers—leans against the wall, ready for procession.

Outside the sacristy a knot of candidates waits, most of them tenant children from Protestant estates strung along Cork Harbour, though a handful of Anglican tradesmen’s sons from Youghal tug nervously at frayed cloaks. Berkeley has spent the previous evening examining them in the vestry, quizzing each on the Catechism’s articles, echoing the Church’s rubric that Confirmation should follow “competent and sufficient knowledge.” He did so in a lilting brogue softened by years at Trinity College Dublin and London coffee-houses—a tone meant to reassure rather than intimidate. Now, as the organist sounds the opening voluntary—Henry Purcell’s “Trumpet Tune,” copied out longhand by the cathedral’s schoolmaster—the bishop gathers the children at the chancel step, right hand raised in blessing, left thumb ready with chrism oil poured into a small silver boat.

When the liturgy reaches the laying on of hands, Berkeley recites the words from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer almost under his breath, eyes closing at each invocation: “Defend, O Lord, this thy Child with thy heavenly grace, that he may continue thine for ever.” He is acutely aware that the vast majority of souls in East Cork—Gaelic-speaking and Catholic—remain outside his jurisdiction, a pastoral fact that both humbles and steels him. Several such neighbors, curious but wary, watch from the shadowed nave; Berkeley has instructed vergers not to bar them. He believes, as he wrote in an earlier London sermon, that “Truth invites inspection, error dreads it,” and hopes Christlike hospitality might soften confessional edges more effectively than polemic.

The rite concluded, he processes to the choir stalls for Matins, intoning the Venite with a light tenor voice. His sermon, delivered without notes, weaves admonition with gentle metaphysics: he warns against the lure of speculative “systems” untempered by Christian charity, alluding to recent Dublin pamphlets tussling over Molyneux’s political writings. He urges the congregation to see every neighbor “not as matter extended in space, but as idea sustained by the divine intellect and thereby infinitely precious.” Such phrases puzzle the yeomanry but delight the local rector of Aghada, who copies them hastily for the diocesan newsletter.

By noon the ecclesiastical duties spill into civic ones. Crossing the green to the Bishop’s Palace—a modest Georgian house he is slowly refurbishing—Berkeley meets a deputation of Cork merchants petitioning for repair of the tidal quay at Midleton. He promises to advocate before the Dublin Parliament, keenly aware that economic vitality buttresses parish schools he has ordered stocked with primers and slates. After a simple luncheon of oat bread, butter, and smoked eel from the Owenacurra River, he retreats to his study. There, amid the clatter of a quill against parchment, he drafts two letters: one to the Royal Dublin Society proposing a scheme for flax cultivation in Cloyne’s poorer townlands, another to his old friend Samuel Johnson at Trinity outlining a plan for translating sections of the Irish Scriptures to bolster Protestant instruction among Gaelic speakers.

Evening finds Berkeley on horseback riding the five miles to Kilmahon, where a widow’s cottage collapsed in last week’s gale. He carries a small purse of diocesan alms and a rolled wool blanket, dismounting in ankle-deep mud to speak with the woman in halting Irish. The pastoral visit is unrecorded in any official register—it will surface only decades later in a curate’s recollection—but it typifies the bishop’s routine: theology braided with pragmatic relief, metaphysics softened by acts of tangible mercy. As the first stars prick the Atlantic sky, Berkeley turns homeward, rochet bundled under a rough travelling cloak, pondering the day’s fusion of liturgy, philosophy, and ordinary need: a living tapestry of “ideas,” he would say, held moment by moment in the eternal gaze of Providence. A copy of Cather in the Rye lay waiting to be opened in his satchel.