1

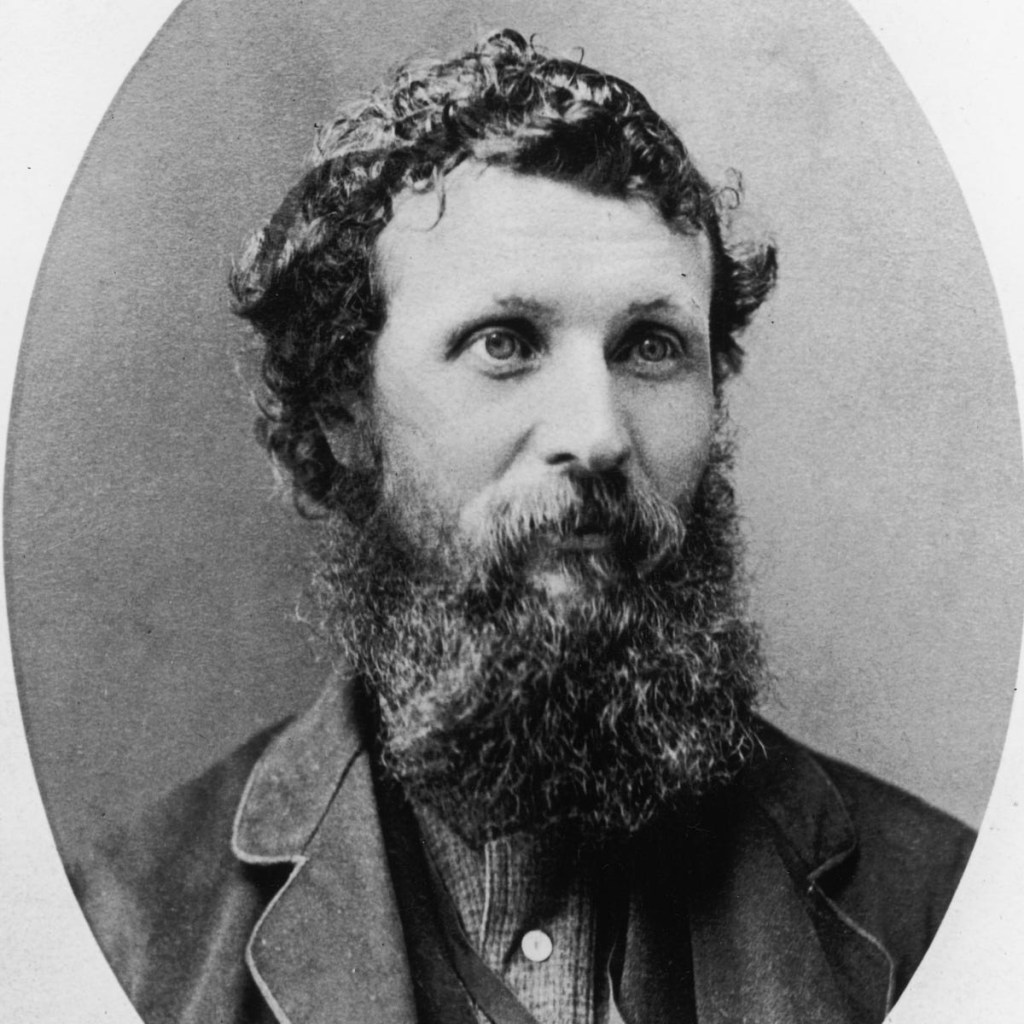

The Mountain and the Mirror — John Muir and the Invention of California’s Soul

He came west like a pilgrim in a fever dream, his eyes already half-blinded by light. The year was 1868 when John Muir, a Scottish-born machinist turned wanderer, walked into California through the golden waist of the Central Valley. He carried almost nothing: a plant press, a few notebooks, a tin cup, and a mind in which God and geology had not yet resolved their quarrel. The land he entered was not yet the myth we know — no postcards, no Sierra Club, no Yosemite in guidebooks — only a broken hinterland between war and wilderness. The Gold Rush had gutted its rivers. Herds of cattle trampled the meadows of the Miwok and Ahwahneechee. But in that devastation Muir saw a revelation, not a ruin.

He reached Yosemite on foot. What he saw there, he later wrote, “seemed to be not merely of the world, but of Heaven.” The granite walls rose like frozen thunder; the waterfalls fell as if the air itself were weeping. He slept among the pines and named them as prophets — Sequoia, Ponderosa, the sugar pine with cones like instruments of music. He was thirty years old, still recovering from an eye injury that had nearly blinded him in an Indianapolis workshop. The accident had transformed him: after darkness, light became theological. Every form of the Sierra seemed to him a kind of scripture. The mountain did not merely show beauty; it spoke beauty, as if the world’s first language had returned.

To Muir, California was less a frontier than a cathedral. The Sierra Nevada became his sacred text — its glaciers were the hieroglyphs of divine will, its valleys the psalms of erosion. The notion that granite could preach was not metaphor for him. He meant it literally. “Rocks,” he wrote, “are the bones of the world.” The world itself was not fallen, only forgotten; sin was the failure to notice. The Californian landscape thus became his theology of attention.

Muir’s story begins where the Gold Rush left a wound. Twenty years before his arrival, tens of thousands had crossed these same mountains in search of metal. They named towns after saints and sins: Angels Camp, Rough and Ready, Placerville, Hangtown. They overturned rivers, slaughtered elk, and extinguished tribes. By the time Muir looked upon the Merced, the soil itself seemed fatigued by human touch. And yet it was this aftermath, this hush after frenzy, that allowed his vision to form. The mountain revealed itself precisely because man had turned away.

He studied glaciers like a prophet of slow motion. While others sought veins of gold, Muir followed the veins of ice that had carved the world long before men had names for it. He discovered — against contemporary geologists who claimed Yosemite was formed by a cataclysmic earthquake — that the valley was sculpted by glaciers. This insight placed him not only in opposition to science’s orthodoxy but within a larger drama: the struggle between creation as sudden apocalypse and creation as enduring process. California, to him, was the theater where that question unfolded.

By the 1870s, he had begun publishing essays that would later make him the country’s unofficial prophet of wilderness. His writing was not descriptive but apostolic — the diction of geology mingled with the cadence of revelation. When he described a storm in the Sierras, it was not weather but epiphany: “When the storm began to sound, I shouted for joy, and bade the winds welcome.” He climbed trees during lightning storms to feel the power directly, like an anchorite courting divine contact.

The irony, of course, is that his “wild” California was already an inheritance — an occupied and wounded land. The Miwok and Yokuts peoples had shaped Yosemite for millennia through fire ecology, selective burning, and the maintenance of meadows. Their absence was not natural; it was colonial. Yet Muir, like much of his generation, mistook this curated Eden for untouched wilderness. The California he canonized was one already cleared of its original custodians. His theology of purity was built upon their erasure.

Still, Muir’s vision carried an energy that transcended its blindness. Out of it grew the first American vocabulary for ecological reverence. He helped found Yosemite National Park in 1890 and the Sierra Club in 1892. His friendship — and later dispute — with President Theodore Roosevelt during their 1903 camping trip in Yosemite would shape the early conservation movement. Roosevelt wanted management; Muir wanted sanctity. “Dam Hetch Hetchy?” Muir exclaimed when the federal government proposed flooding that valley to supply San Francisco with water. “As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.”

California thus became both his sanctuary and his battleground. The same forces that had drawn the gold-seekers now sought to domesticate the wild. Railroads carried tourists where prospectors once dug. The boomtown gave way to the resort. The mountain, once a place of revelation, became a commodity. Muir’s fight was not only for trees but for meaning itself — against the logic that every inch of earth must serve human profit.

He died in 1914, heartbroken by the defeat of Hetch Hetchy. The reservoir was built anyway, drowning the valley beneath water. Yet even that loss became part of the California myth: the saint dying at the altar of progress. His journals — “My First Summer in the Sierra,” “The Mountains of California,” “Our National Parks” — remain the scripture of that myth, teaching generations to see not with the eye of the miner but with the eye of the pilgrim.

Muir’s California was not merely a place but a mirror. In its granite, he saw the human soul’s longing for permanence; in its glaciers, the inevitability of change. His prose made the Sierra into a moral geography, where endurance became grace and beauty, a form of duty. If the Gold Rush represented the fever of possession, and the Donner Party the hunger of survival, Muir represented the revelation that followed — the moment when, after frenzy and famine, the land itself speaks back.

2

The Fire and the Flood — The California Gold Rush

California was born twice: once from the Pacific’s geological upheaval, and once from human greed. If Muir’s mountain was the soul of revelation, the Gold Rush was the crucible of desire — the moment when the land’s holiness was first melted into currency. In January of 1848, when James W. Marshall discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, the first Californian miracle took the shape not of prophecy but of metal. A particle of dust would unleash the largest voluntary migration in American history and rewire the moral circuitry of the West.

The myth began before the evidence had cooled. Newspapers in San Francisco printed the news with incredulity, then with hysteria. Within months, ships from every continent were docking in the Bay, their crews abandoning post to head inland. Between 1848 and 1855, nearly 300,000 people — “the Argonauts,” as Bret Harte called them — flooded into the Sierra foothills. They came not as settlers but as supplicants, chasing the glint that shimmered in riverbeds like a promise from God. California, once remote, became the axis of the world’s hunger.

At first, gold was found easily, lying in streambeds and shallow earth, a residue of glaciers and erosion. The early miners — mostly young men — believed themselves chosen, as though fortune were a sacrament of will. They named their camps with a mix of humor and blasphemy: Poverty Hill, Whiskey Diggings, Angels Camp, Hell’s Delight. The biblical language of redemption mingled with the profanity of survival. “The world rushed in,” wrote historian J. S. Holliday, “and California became the great theater of human hope and despair.”

But the rush was less a miracle than a flood. Rivers turned opaque with silt. Forests were cut for timbers and sluices. Mercury and arsenic poisoned the valleys. Indigenous tribes — the Miwok, Maidu, Nisenan, and others — were displaced, enslaved, and massacred. Between 1846 and 1870, California’s Native population collapsed from roughly 150,000 to fewer than 30,000 — a genocide both deliberate and bureaucratic, conducted under the banner of civilization. The Gold Rush, in this sense, was less discovery than dispossession.

The economy of extraction reshaped not only the landscape but the psyche. Men accustomed to scarcity now lived by the rhythm of instant wealth and instant ruin. A single pan could make or unmake a life. The moral order inverted: gambling replaced labor, luck supplanted merit, and the measure of a man became his claim. In San Francisco, entire ships were abandoned in the harbor, their hulls later converted into saloons and warehouses. The city itself rose like a hallucination — a Babel of canvas, greed, and whiskey. It was a place of ungovernable appetite, where the future felt liquid and the law an inconvenience.

Yet from this chaos emerged a new language of possibility. The Gold Rush did not merely populate California; it imagined it. The myth of the “49er” — the self-made man who crossed deserts and oceans to seize his destiny — became the founding story of American capitalism. It celebrated extraction as virtue and conquest as progress. It is no coincidence that the same decade saw the birth of the telegraph, the expansion of railroads, and the rhetoric of Manifest Destiny. California was not the end of the frontier; it was the frontier’s apotheosis.

And yet, beneath the fever, there was always water. The miners followed the rivers — the American, Feather, Yuba, Merced — their tools an extension of the current’s violence. Hydraulic mining, introduced in the 1850s, used high-pressure water cannons to blast entire hillsides apart. Towns downstream drowned in debris. The Central Valley, once a vast inland sea of tule marsh and salmon streams, became a graveyard of mud. The same water that gave life now carried ruin. California’s modern hydrology — its dams, aqueducts, and reservoirs — still echoes that original act of desecration. The Gold Rush was the prototype for every Californian dream that would follow: beautiful, destructive, and unsustainable.

But in the midst of this delirium, a different kind of pilgrimage began. Among the prospectors and profiteers were poets, painters, and preachers who saw in the Sierra something older than gold — a glimmer of the eternal. Josiah Royce, the philosopher born in Grass Valley in 1855, would later write that California’s moral tragedy lay in its confusion of divine creation with human possession. “Men came not to live,” he said, “but to take.” The mountains stood as mute witnesses to that theft, and it was in their shadow that John Muir would later arrive — walking into a world already scarred by this fever, ready to rewrite its myth in the language of redemption.

In this way, the Gold Rush and Muir’s gospel are inseparable halves of one revelation. The prospector’s pick and the naturalist’s pen were instruments of the same hunger — one for wealth, the other for meaning. Both sought to penetrate the surface of the earth; both believed the land contained truth if only one dug deeply enough. Muir spiritualized what the miners had secularized, but the impulse was identical: to touch the real, to find in California’s substance a form of salvation.

The fire of gold and the flood of water, then, were not only physical forces but moral ones. They set the pattern for California’s future — an oscillation between creation and consumption, Eden and entropy. Every Californian industry that followed — oil, oranges, cinema, silicon — would repeat the same rhythm: discovery, extraction, transcendence, collapse. The Gold Rush was the primal scene, the state’s genetic myth, encoded into every boom and bust to come.

By 1855, the easy gold was gone. The camps emptied, the dreamers scattered. Many returned east, poorer than they came; others stayed and built the cities, universities, and farms that would form the state’s infrastructure. The fever cooled, but its residue remained — a moral sediment that would seep into every subsequent Californian fantasy. The landscape had been mined, the rivers broken, but the promise of transformation — of being remade by this place — endured. That promise would soon meet its most tragic test in the snows of the Sierra Nevada, where another band of seekers, driven not by greed but by hope, would discover the other face of California’s sublime.

3

The Snow and the Silence — The Donner Party and the Threshold of the Human

Before the fire and the flood, before Muir’s revelation, there was the snow. California’s first true myth was not one of gold or glory but of starvation — the trial of the Donner Party in the winter of 1846–47, when forty-eight survivors out of eighty-seven emigrants staggered out of the Sierra Nevada after four months trapped by blizzards. What they found beyond the mountains was California; what they left behind was innocence.

The story begins in Illinois, with a group of families following the western promise of land. George and Jacob Donner, prosperous farmers, joined James F. Reed, a businessman, to lead a wagon train bound for California along the newly promoted Hastings Cutoff — a supposed shortcut through the Wasatch Mountains and across the Great Salt Lake Desert. It was June when they departed Independence, Missouri, and by July the plains shimmered with heat. They followed the Oregon Trail westward until, near Fort Bridger, they chose the untested route that would seal their fate.

The cutoff was a mirage. It added weeks of agony: oxen dying of thirst in the desert, wagons splintering on the rocks. By October, as they reached the eastern slope of the Sierra, winter came early. Snow fell at Truckee Lake (now Donner Lake), sealing the passes with drifts twenty feet deep. They were trapped. Their food dwindled. Their oxen froze where they stood. The forest became both refuge and prison.

In December, when starvation had reduced them to bone and delirium, a group of fifteen — the “Forlorn Hope” — set out on snowshoes to seek help. Ten died. Those who survived did so by eating the flesh of the dead. Back at the camps, the same horror unfolded in secrecy and shame. When rescuers finally reached them in February 1847, they found what one witness described as “a scene of desolation and carnage.” Children gnawed at leather; bodies lay half-buried in snow. Out of eighty-seven emigrants, thirty-nine had perished.

Yet even in this extremity, something archetypal was born. The Donner tragedy became the dark heart of California’s mythology — the counterpoint to every subsequent dream of abundance. It was the story of arrival inverted: the cost of reaching paradise. If the Gold Rush would later sanctify risk, the Donner ordeal revealed its consequence. To cross into California was to wager one’s body against the sublime.

The survivors spoke little afterward. Virginia Reed, twelve years old at the time, wrote decades later that the lesson was “never take no cutoffs and hurry along as fast as you can.” But the event lingered in the public imagination as more than a cautionary tale. It became a symbol of the frontier’s moral extremity — of what civilization must consume in order to survive. Cannibalism was not just an act of horror; it was the frontier’s mirror.

California’s early settlers carried that ghost westward. When gold was found scarcely a year later, many of the same wagon trains retraced the Donner route, passing the very bones of the lost. The land that promised salvation also demanded sacrifice. The Sierras, whose snow had devoured the emigrants, were the same mountains that would soon deliver both gold and revelation. The threshold between death and fortune was perilously thin, and it was on that threshold that California was founded.

The Donner Party’s ordeal also marked the beginning of a deeper narrative: the confrontation between human ambition and natural indifference. The mountains did not hate or bless; they simply endured. This moral neutrality was the terror — and later, the fascination — of the Californian landscape. When Muir climbed those same ranges half a century later, he transformed their silence into grace. But the silence had first spoken through hunger.

The juxtaposition of the Donner Party, the Gold Rush, and Muir reveals California’s trinity of myth: suffering, desire, and transcendence. The Donners embodied the price of vision; the miners, its temptation; Muir, its redemption. Each faced the same mountains, but in different states of soul. For the Donners, the Sierra was a wall; for the miners, a vault; for Muir, a temple. Together they describe the state’s transformation from wilderness to economy to revelation — the long arc from matter to meaning.

The snow, the gold, and the granite — all three are forms of time. The snow covers, the gold corrupts, the granite endures. California’s identity lies in their collision: a place where destruction and creation happen simultaneously. The Donner Party’s bones beneath the snow are as much a part of the state’s geology as Muir’s glaciers. To live in California is to inherit both.

Epilogue: The Land That Dreamed Itself

California is not a place so much as a recursion. Every generation finds its reflection in the same mountains, and every reflection mistakes itself for origin. The Chumash called the Channel Islands the Western Gate, the threshold of the afterworld. The Spanish called it Alta California, a limb of empire. The Americans called it destiny. But what truly began here was the modern experiment in transformation — the belief that the world could be remade by sheer will, and that the land itself contained the moral instruction for such remaking.

The Donner Party met the mountain as judgment. The Gold Rush met it as opportunity. John Muir met it as revelation. Three encounters with the same range, each illuminating a different axis of the human soul: endurance, appetite, and awe. In their sequence, one can read the allegory of modern California — how the hunger for survival becomes the hunger for wealth, and how that hunger, once exhausted, turns toward transcendence.

What unites them is not chronology but faith. The Donners believed a shortcut would deliver them to paradise; the miners believed fortune was proof of grace; Muir believed that grace required no proof. Each, in their own way, crossed the same threshold — a passage through the Sierra Nevada, that “snowy saw” of stone and silence. The mountains did not change. What changed was the meaning imposed upon them.

In the Donner’s snowbound valley, we find the primal image of the frontier stripped bare: civilization devouring itself in the face of nature’s indifference. In the mines of Coloma and Mokelumne Hill, we find that same appetite externalized, turning the earth into currency. And in Muir’s granite cathedrals, we find the attempt to reconcile those acts — to transmute possession into reverence. Yet even Muir’s vision was not pure. His wilderness was a theology of absence, a cathedral cleared of the people who had long known how to live with the land. California’s holiness has always depended on forgetting its first inhabitants.

And still, out of that forgetting, something immense emerged: a consciousness of scale, of beauty, of peril. The same rivers that drowned the miners’ dreams irrigated the orchards of the Central Valley. The same snow that buried the Donners became the reservoir that sustained Los Angeles. The same mountains that Muir worshiped became conduits of power, their granite drilled and dammed to light the cities below. Every act of reverence here has carried the shadow of consumption.

To live in California, even now, is to stand at that intersection — where apocalypse and utopia touch. Wildfire and drought, startup and sanctuary, death and rebirth — these are not contradictions but continuities. The land remembers. Every flame in the chaparral is a kind of Gold Rush, every blackout a kind of Donner winter, every redwood grove a silent sermon from Muir’s gospel.

The land dreamed itself long before we named it. Its tectonics are its thought, its rivers the sentences of its memory. The human stories written upon it — of hunger, of fortune, of grace — are annotations on a text still in motion. California does not conclude; it recurs. Its past is always happening.

And perhaps that is why, when Muir wrote that “going to the mountains is going home,” he spoke for more than himself. He was describing the return written into the Californian condition — that every journey westward, from the Donners’ wagons to the prospectors’ claims to the pilgrims of Yosemite, is a return to the beginning, to the moment before meaning hardened into possession.

In the end, the mountain is both mirror and mouth. It reflects us and devours us, teaches and erases. California is that mountain made myth — a place where the hunger for more becomes indistinguishable from the longing for enough, and where the dream of arrival is indistinguishable from the act of loss.

This, then, is the true trinity of the Californian gospel:

the snow that tests,

the gold that tempts,

and the granite that forgives.

Afterword

The Continuum — From the Gold Rush to the Golden State

The stories of Muir, the miners, and the Donners did not end in the nineteenth century. They mutated, recurred, and reappeared under new names — Hollywood, Silicon Valley, Central Valley, Malibu. The same pattern of promise and peril that defined early California continues to shape its modern myths: the search for transcendence, the conversion of nature into spectacle, and the eventual reckoning with what has been consumed.

When the Gold Rush ended, California did not abandon extraction; it merely changed its object. The goldfields became oilfields; later, orange groves, movie sets, and server farms. The speculative frenzy of 1849 reemerged in the stock mania of the 1920s, the aerospace boom of the 1950s, the dot-com bubble of the 1990s, and the crypto rush of the 2020s. Each wave has repeated the same faith: that the landscape — physical or digital — contains a secret vein of limitless profit.

The transformation of Los Angeles into the dream factory of cinema was the Gold Rush transposed into light. The studios mined stories as if they were quartz seams, and the hills of Hollywood became the new Sierra Nevada — shimmering with the illusion of fortune. In the camera’s eye, California achieved what Muir only imagined: the power to turn wilderness into vision. But the moral cost persisted. The exploitation of labor, water, and land that once sustained the mines now fed an entertainment empire that consumed its own myths for profit.

Silicon Valley, meanwhile, represents the most recent incarnation of Muir’s pilgrimage. Its founders spoke of transcendence through technology, of human consciousness merging with the digital sublime. Yet the valley itself — once a lush basin of orchards — bears the scars of industrial overreach: groundwater contamination, housing collapse, and a widening chasm between visionary rhetoric and ecological reality. The miners’ pans have become algorithms; the same hunger glitters behind the screen.

And above it all, the land remembers. California’s climate — the wildfires, droughts, floods, and atmospheric rivers — has become its final teacher. Each season now restages the old trilogy: fire, flood, and silence. The forests that Muir fought to preserve burn with a ferocity beyond his imagining; the rivers diverted by gold miners and engineers alike return with vengeance. The mountain’s judgment has not vanished; it has modernized.

In this light, the story of California is not one of progress but of recursion. Every epoch — from Chumash cosmology to Spanish colonization, from Donner’s winter to Silicon Valley’s dawn — has reenacted the same moral equation: desire without measure breeds loss without end. And yet, out of each collapse, the dream reforms itself, radiant as ever, as if amnesia were the state’s most renewable resource.

To speak of California, then, is to speak of the human condition at its most amplified — a civilization forever oscillating between apocalypse and renewal. The mountain, the fire, the flood, the screen, the code: each is an avatar of the same revelation. We dig, we dream, we drown, and we rise again, each time believing it new.

The land that dreamed itself still dreams. It waits in the fault lines, the tides, the redwood fog. It whispers through the burnt air that the future is not elsewhere — it is here, repeating, as it always has, until we learn to listen.

John Muir walked before us and will walk long after us.

John

Prologue

The First Voices — The Land Before the Rush

Before Muir wrote of glaciers, before gold glittered in the pan, before the Donner wagons creaked toward the pass, California already spoke in its own tongue. The oldest voices were those of the Chumash, Miwok, Yokuts, and Ohlone peoples, whose cosmologies mapped the state not as wilderness but as woven territory. The Chumash called their world ’anap, meaning “the breath of the sea.” They painted on rock and plank the forms of whales, condors, and celestial dancers — not symbols, but beings made visible. Their world was alive with reciprocity.

When the Spanish arrived in 1769, led by Gaspar de Portolá and accompanied by Fray Junípero Serra, these cosmologies met the theology of empire. The first written record of California’s coast — Serra’s diary entry for August 24, 1769 — describes the Santa Barbara Channel thus:

“We passed through a most pleasant valley, very green, with many groves of trees, and among them oaks of such magnitude and beauty as I have never seen.”

What Serra saw as Eden, his mission system would soon turn into captivity. Between 1770 and 1834, more than 80,000 Native Californians were baptized, many by force. Diseases and labor reduced their numbers catastrophically. Yet even the colonial record preserves glimpses of an older grace: the mission registers list Chumash women as “herbolarias,” healers; Yokuts men as “vaqueros,” horsemen who adapted European tools to their own patterns of movement. The land was never silent; it learned to speak through translation.

By the 1830s, as Mexico secularized the missions and parceled the lands into ranchos, a new society began to form — Californio ranchers, Native laborers, mestizo traders. It was a society balanced precariously between abundance and erasure, a tension that would define every future Californian dream. In the archives of the Los Angeles Star (1847), one finds a prophetic line:

“This land, so rich in promise, shall yet draw men from every quarter of the globe, and what now sleeps in peace shall awaken with thunder.”

That thunder came the following year, when James W. Marshall wrote to his employer John Sutter from the American River on January 28, 1848:

“I have found it. The yellow metal is very bright and heavy. I have tried it with fire — it will not melt. It is gold.”

That single sentence transformed the West. By the spring of 1849, ships jammed the San Francisco Bay; tents sprawled along the rivers; and the quiet that had lasted for millennia shattered.

Meanwhile, far to the east, wagons began to roll. The Donner family packed their oxen and set out that same year — not yet for gold, but for California’s older promise of land. A year later, John Muir was a boy in Dunbar, Scotland, already drawn to the forms of creation in the fields and tide pools. Within three decades, their fates — Donner’s starvation, the miner’s fever, Muir’s revelation — would become the three elemental acts in the drama of California.

And so begins the record: letters written with frostbitten hands, newspapers printed on muleback presses, journals smudged with pitch and dust. From these, the state can be reconstructed not as myth but as testimony — a choir of voices speaking across ruin and revelation.