(Prelude)

Art is a knife. Not a warm blanket, not a therapist’s couch – a blade. True art doesn’t soothe; it slashes. It cuts through lies and sanctioned truths, drawing blood from the sacred and the powerful. For as long as cowards have built thrones and altars, artists have been the ones mad enough to grab the knife and slice at the foundations. History is a blood-soaked gallery of those who dared to make art that wounds: each stroke of the pen or brush a defiance, each metaphor an act of revolt. Institutions – emperors, priests, inquisitors – have always trembled before this unruly power. They brand it heresy, treason, obscenity, because deep down their gilded authority is paper-thin, terrified of a well-aimed cut.

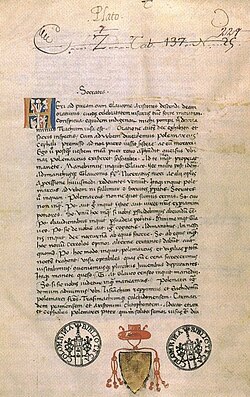

The five figures in this essay – Plato, Ovid, Hallāj, Giordano Bruno, and the Marquis de Sade – each took art or language as a knife and pressed it against the neck of their epoch. They showed that creation can be an act of destruction: a rebellious shout of “Fuck you!” to the order of things. We begin in ancient Athens and end in the modern world, tracing how dangerous ideas have always been met with exile, fire, gallows, and silence – and why wielding the knife of art remains a perilous, necessary act.

A marble bust of Plato, copied from a 4th-century BC original by Silanion. Plato saw his teacher executed for impiety and later risked his life to challenge tyrants with philosophy .

Plato was not the gentle academic our modern age sometimes imagines – he was an insurrectionary of the mind. He came of age in a city that murdered his mentor Socrates for the crime of speaking truth. Plato “had lived through…the execution of his beloved teacher Socrates by a jury of his fellow Athenians” , an act of democratic cowardice that seared into him the understanding that society’s “justice” was often mob fear in robes. In response, Plato fashioned philosophy into a weapon against the moral and metaphysical frameworks of his time. Athens worshipped its gods and its democracy, but Plato dared to say that most men live in a cave of shadows – mistaking flickering illusions for reality. In his vision, the true Good was something higher, a blazing sun of truth accessible only to those who would turn away from convention. This was a direct assault on the comfortable pieties of Athens: if the multitude and their storytellers (the poets, whom Plato famously would exile from his Republic) were deluded, then the entire moral order of the city was built on lies.

But Plato did not stop at theory. In one of history’s most mythic episodes, the philosopher tried to actualize his radical ideals in the world of power. He traveled to Sicily to test the idea of the philosopher-king, attempting to school the tyrant Dionysius of Syracuse in wisdom and virtue . Imagine the audacity: a lone thinker lecturing a decadent despot on how to rule justly. Dionysius – a paranoiac surrounded by sycophants and bloodied blades – listened as Plato told him that true happiness demanded justice and moderation, not orgies and gold . The tyrant bristled. Who was this Athenian to scorn the banquet and the whip? Plato even insisted that a man enslaved could be happier than a corrupt king, if his soul were just . Dionysius answered this philosophical sermon with an exquisite piece of sarcastic brutality: he sold Plato into slavery . The message was clear – so much for your “philosopher-king,” now taste the whip yourself. According to Plutarch, Dionysius sneered that if Plato’s philosophy of the soul were true, the man would remain happy even as a slave .

Thus Plato’s life itself became a paradoxical artwork of defiance. He literally put himself in the lion’s den to prove a point about truth and power. Though friends soon ransomed him out of chains , the incident stands as one of antiquity’s great symbolic persecutions of thought. Plato’s assault on the dominant framework – whether Athens’ democratic relativism or Syracuse’s tyrannical hedonism – nearly cost him his life. The established order struck back with exile and bondage, the age-old answer to uncomfortable ideas. Yet Plato survived to found his Academy, taking revenge in the realm of writing. In dialogues like The Republic, he revealed his dangerous truths openly: that most societies are caves and most leaders fools, and that only a radical revaluation of values (philosophy enthroned as king) could set humans free. This was intellectual regicide – a proposal to overthrow the very basis of who should rule. It made him subversive in his era and every era since. The civilized Athenians had poisoned Socrates; the “civilized” world would likely have done the same to Plato had his ideas not been safely tucked into innocuous pages. But make no mistake, Plato’s art cut at the jugular of Greek morality and politics. He turned language into a blade aimed at the heart of ignorance. In doing so, he became the archetype of the philosopher as threat to the status quo – a man who barely escaped the fate of his teacher and proved that thought itself can be treason.

Statue of Ovid in Constanța (ancient Tomis). The poet was banished to this remote Black Sea outpost by Emperor Augustus for the subversive decadence of his verses .

In the golden age of Augustus – a regime draped in slogans of a “restored morality” – Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid) laughed at the pretenses of purity and paid for it in bloodless but cruel coin: exile. Where Rome’s first emperor marched in triumph, reforming laws against adultery and praising austere virtue, Ovid danced with words about erotic intrigue and the art of seduction. His very pen was a dagger to Augustan hypocrisy. In Ars Amatoria (“The Art of Love”), Ovid became a merry heretic of love, teaching Romans “how to pick up girls outside the Forum” and mocking the new imperial prudery . This was a direct assault on the dominant moral framework of the time. Augustus had cast himself as the moral savior of Rome, enforcing chastity through law, even banishing his own daughter for her affairs . Yet here came Ovid, Rome’s favorite poet, glorifying adultery with a wink and a nudge – a carmen (poem) that flouted the emperor’s entire social agenda.

The blow struck home. In 8 CE, Ovid was banished to the ends of the earth – the Black Sea town of Tomis – by Augustus’s decree . No trial, no appeal: one day the poet was at the pinnacle of Roman society, the next he was damnatio in the flesh, condemned to live among barbarians who didn’t speak Latin . He himself chalked it up to “carmen et error” – “a poem and a mistake” . The poem was surely the Ars Amatoria, which had been circulating for years but suddenly became intolerable . The “mistake” remains mysterious; Ovid only hints that he had seen or known something he shouldn’t have (perhaps a scandal in the imperial family). But Roman scholars agree that the real crime was the poem’s insult to Augustus’s moral crusade. The emperor “was presenting himself as the restorer of Roman public morality and could not fail to punish an author…who represented himself in the Ars Amatoria as a promoter of adultery in defiance of the Emperor” . Ovid, with jaunty elegance, had basically yelled “Fuck your rules” to the powers of his day – and the powers struck back, hard.

In the windswept misery of Tomis, Ovid lived out his days writing plaintive elegies, begging for mercy that never came . Augustus and later Tiberius left him to rot on civilization’s edge. This was a censorship by cold steel: not the quick martyrdom of an execution, but the slow suffocation of a voice. Augustus even banished Ovid’s books from Rome’s libraries , as if to scrub the capital clean of his subversive influence. What was it about Ovid’s art that so threatened the regime? Partly it was the mirror he held up to imperial hypocrisy. Not long before Ovid’s exile, Augustus’s own daughter (and Julia the Younger, his granddaughter) were caught in adultery and disgraced . The emperor’s house was hardly pure, yet Ovid’s playful verses of pleasure became the scapegoat. Ovid revealed that beneath the toga of Augustan virtue lay the same flesh and passions as ever. His Metamorphoses, meanwhile, wove tales of gods behaving badly – Jupiter’s lusts, Venus’s whims – undermining any pretense that Rome’s divine patrons were models of decorum. Change and desire were the truths of the world, Ovid implied, not any fixed moral code.

This truth – that life is flux and desire fundamental – was dangerous in a regime built on “traditional values.” Ovid’s punishment shows that even a poet with a quill can shake an empire. By turning love into open rebellion, he transgressed the unwritten law that art should serve power’s narrative. Instead, his art cut like a razor through the façade of moral supremacy. The powers of order answered by casting the poet out into chaos. Ovid died in exile, far from Rome. But Augustus could not kill his words. They survived, underground at times, inspiring generations with their sly subversion. “My name shall never perish,” Ovid wrote, and he was right – he outlived Augustus in memory, his art a knife that kept cutting long after the hand that forged it turned to dust.

If Ovid’s transgression was of morals, Abū al-Mughīth al-Husayn ibn Manṣūr al-Hallāj – known as Hallāj – committed a sin far more incendiary: a metaphysical treason. In the Islamic empire of the 10th century, Hallāj stood up and proclaimed “Ana al-Haqq” – “I am the Truth,” meaning I am God. With that one ecstatic utterance, he set a torch to the entire orthodox framework of Allah apart from His creation. In Islam, Al-Haqq (The Truth) is one of the names of God; Hallāj’s claim was nothing less than mystical union – or blasphemy in the eyes of the ulema. He was “condemned for heresy on account of the ecstatic utterances of ‘I am the Truth,’ or ‘I am God’” . But the power of Hallāj’s art was in its living performance: he didn’t just write or say something; he became a sacrificial icon. His life and death were his artwork, crafted to reveal a truth that orthodox religion could not stomach.

Hallāj was a Sufi – a seeker of divine love so ardent that he lost himself entirely in the divine. He wandered, preached, and inspired disciples with a message that God is not a distant monarch but the very core of our being. This was an assault on the dominant metaphysics of the Caliphate, which insisted on a vast gulf between Creator and creature. Hallāj closed that gap in a scandalous embrace. “O Muslims, save me from God,” he cried, drunk on the annihilating wine of love . He even urged his own execution – “God has made my blood lawful to you: kill me,” he said – turning his fate into a deliberate provocation. For a time, the powers were hesitant; some authorities refused to condemn him, saying his inspiration lay beyond their jurisdiction . But Hallāj’s growing popular following, coupled with political intrigue, sealed his doom. The Abbasid court denounced him as a dangerous heretic. Officially he was charged as a threat to the state – accused absurdly of being a Qarmatian rebel plotting to destroy the Kaaba – because even for a Caliph, charging someone with simply saying “I am God” was awkward. But everyone knew his true “crime” was this unforgivable blurring of man and God, the ultimate transgression against Islamic dogma.

In March 922, Hallāj was led out of his Baghdad jail before a howling crowd. What followed was sheer brutality, a spectacle of pious vengeance. They beat him in the face, flogged him until he fell unconscious, then cut off his head . Not content, the executioners crucified his corpse and set it on fire, scattering his ashes into the Tigris River . One report even says Hallāj smiled in his agony, his last breath spilling out words of mystical devotion: “All that matters for the ecstatic is that the Unique should reduce him to Unity.” . Thus died the man who dared to utter the secret that the divine lives within us. The punishment was meant to terrify – and it did. For centuries, Hallāj’s name in Muslim lands was a cautionary tale: stray beyond the bounds of sanctioned truth, and you will be annihilated.

Yet in that violent end is a perverse triumph of his art. Hallāj had always spoken of fanaa’ – the annihilation of the self in God. By accepting the most horrific execution, he lived out his philosophy to its limit, performing the very unity he preached. His executioners – those “educated” cowards of law and doctrine – believed they were silencing a devil. In truth, they were enacting the final chapter of a passion play Hallāj himself had written with his life. The world-breaking truth he revealed was that the individual soul can merge with the absolute, that love can dissolve the boundaries set by priests and jurists. Such an idea explodes the power of any religious institution, for if I and Truth are one, who needs the ulemas and caliphs? The guardians of orthodoxy understood this threat perfectly. They answered with ropes, blades, fire. Hallāj’s blood stains the annals of history – a reminder that metaphysical rebellion is paid in flesh. But his legend, his poems, and the reverence of later Sufis (like Rumi, who saw Hallāj as a saint) all testify that the knife of art – in this case, spiritual poetry and lived symbolism – can cut through even the “absolute truths” enforced by empire. Hallāj wielded his faith like a dagger against the fabric of Islamic convention, and though it killed him, it did not kill his truth. His ecstatic “I am God” still echoes, undimmed by a thousand years, daring us to ask what divine spark might be found in our own hearts when we challenge the powers that be.

Bronze statue of Giordano Bruno in Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori, where he was burned alive in 1600. Bruno’s cosmology and heresies defied the Catholic Church’s entire worldview .

Toward the end of the Renaissance, in an age when the Catholic Church still enforced a monopoly on cosmic truth, Giordano Bruno lit a bonfire under the certainties of his time. A defrocked Dominican friar turned wandering philosopher, Bruno preached an infinite universe – a cosmos filled with innumerable suns and worlds . He embraced cosmic pluralism and hinted those other worlds might harbor life . In one stroke, this idea relegated Earth and by extension the Church’s esteemed man to just one speck among countless others. Bruno also espoused a kind of mystical pantheism (believing God was immanent in all of nature) and dared to question core Christian doctrines. He denied the Trinity, the virginity of Mary, the unique divinity of Christ – effectively digging at the pillars of Catholic orthodoxy . Here was a man who wielded imagination and reason like a twin-edged blade, slicing through the closed medieval cosmos and the Church’s spiritual authority in one go.

For the ecclesiastical establishment, Bruno’s ideas were beyond toleration. He was arrested by the Inquisition and dragged through a seven-year trial. In the end he was charged with “denial of several core Catholic doctrines, including eternal damnation, the Trinity, the deity of Christ, the virginity of Mary, and transubstantiation” . Bruno, unbowed, refused to recant his visions of an unfettered universe. The inquisitors, those professional liars of God, found him guilty of heresy and condemned him to death. On February 17, 1600, in Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori, they made a public example of him. Tongue in iron, flames climbing high – Bruno was burned alive for the crime of thought. Eyewitnesses say he refused even a last-minute mercy: when offered a crucifix to kiss, he turned his head away in contempt . One account has him telling his judges, “Perhaps you pronounce this sentence with greater fear than I receive it.” Unrepentant to the end, he stood as the fire swallowed him. He “declared an unrepentant heretic and excommunicate, he was burned alive in the Campo de’ Fiori in Rome” . It was Ash Wednesday – fitting, as ashes is all the Church would leave of this brilliant mind.

What truth did Bruno reveal that was so threatening? In simplest terms, that the universe did not conform to the Church’s story. In Bruno’s infinite cosmos, the Earth was not the center, Man was not necessarily the pinnacle, and God’s creation was far vaster (and perhaps stranger) than the Bible implied. If stars were suns and worlds without end orbited them, then who was to say Christ’s sacrifice on one tiny globe could be the sole drama of salvation? Bruno’s heresy was cosmic and theological: he exploded the closed Biblical cosmos into endless space and implicitly multiplied mysteries the Church could not answer. He also asserted the daring notion that no institution could monopoly truth – truth was written in the stars and the very substance of reality, not in the decrees of men in robes. “Bruno’s case is still considered a landmark in the history of free thought and the emerging sciences” , precisely because he died refusing to let enforced dogma snuff out the candle of reason.

As the flames consumed Bruno, one contemporary wrote, “On the stake, along with Bruno, burned the hopes of many” – hopes that one might reconcile free thought with the dominant faith . The Church, declaring itself “custodian of absolute truth,” insisted on this auto-da-fé as a warning . It worked – for a time. Minds like Galileo’s certainly got the message (Galileo would recant under threat rather than share Bruno’s fate). But in the long run, the ideas Bruno died for could not be burned away. The infinite universe, the plurality of worlds, the freedom to think beyond scripture – these became cornerstones of the modern scientific outlook. Bruno’s death was a bloody incision in history: the moment when the knife of art (in this case, the art of radical philosophy and poetic cosmology) cut so deep into the body of doctrine that the wound eventually widened into the Enlightenment. Bruno showed that to seek truth, one must be willing to be branded heretic. In his execution, the Church won the battle but lost the war: they created a martyr of the mind. Four centuries later, a bronze statue of Bruno broods over the square where he perished – a permanent “fuck you” cast in metal, glaring at the Vatican. The knife he wielded was thought itself, and it proved sharper than any pyre; the wielder turned to ash, but the idea of intellectual freedom emerged fireproof.

If Plato, Ovid, Hallāj, and Bruno each wielded the knife of art against heaven or societal order, then Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade took that blade and carved directly into the soft flesh of human morality. Sade was an aristocrat born in a gilded cage of privilege in pre-revolutionary France – precisely the class expected to uphold church, king, and decency. Instead, he became history’s most infamous literary sadist, a writer-philosopher who gleefully shattered every moral and metaphysical boundary. In his dark novels and dialogues, Sade proclaimed a truth so obscene and dangerous that society had to lock him away for decades and bury his works for centuries. His life was a litany of prison cells: “for much of his adult life the Marquis de Sade was confined in prisons and insane asylums”. Why? Not merely for his personal debaucheries (though those were scandalous enough), but because his ideas were anathema. Sade’s pen was a poisoned dagger aimed at the heart of organized religion, conventional morality, and even the Enlightenment’s hopeful humanism. He wrote that God is a fraud, virtue a weakness, and the only law is the law of appetite and power. In an age of reason and revolution, Sade offered a grim counter-gospel: Nothing is true, everything is permitted – provided you have the strength to enforce your will.

The Marquis de Sade’s assault on the moral framework was total. He taunted the Church with blasphemy and the philosophes with ruthless logic carried to nihilistic ends. In his dialogue Philosophy in the Bedroom and in Justine, he systematically inverts every sacred value. Rape, torture, incest, sacrilege – all depicted in pornographic detail not just to shock, but to drive home a philosophical point: that Nature cares nothing for our moralities. Sade dared to say that if a cruel act gives pleasure to the powerful, then by nature’s standard it is good. He turned liberty into an absolute weapon: total freedom of the individual, even to destroy others, as the ultimate truth of human desire. Such ideas, if taken seriously, threatened to unravel the very fabric of society – law, faith, empathy, all revealed as arbitrary constraints. No wonder the institutions of his time responded with swift repression. His writings “were banned in France until the 1960s” (long after his bones crumbled). In fact, Sade’s books were immediately outlawed upon publication and often destroyed; Justine was published in secret and earned him a special place in Napoleon Bonaparte’s crosshairs. The great conqueror Napoleon, ruling France as First Consul, took it upon himself to personally ensure Sade was silenced. In 1801, after Sade anonymously published Justine and Juliette, Napoleon ordered his arrest. The aging Marquis was seized and thrown into Charenton asylum without trial . His “repeated protests had no effect on Napoleon, who saw to it personally that de Sade was deprived of all freedom of movement” . Imagine: the most powerful man in Europe so frightened by a book that he locks the author away and throws out the key. That is the measure of how dangerous Sade’s knife of art was perceived to be.

Sade spent about 30 years of his 74-year life behind bars, including a decade in the Bastille and his final years in the asylum where he died in 1814 . They hoped to bury him in oblivion. Indeed, for a long time his name itself was effectively erased – his family was so ashamed that “for five generations, the Marquis’s name was taboo… as if there was an omertà against him” . Yet, as with all these transgressors, repression only delayed recognition. Sade’s dangerous truths slithered out through underground copies and furtive literary whispers. What were those truths? That civilization’s moral codes are lies we tell to mask the truth of desire and power. Sade revealed humanity’s inner wolves – the lust, aggression and urge to domination that polite society conceals. In his worldview, the real atheism was not just denying God, but denying any binding distinction between good and evil. Such a revelation is too much for most to bear; even today, reading Sade is a harrowing experience. But he forces the reader to confront hypocrisy: the churchman who preaches virtue yet exploits children, the judge who condemns crime yet relishes punishment. Sade turned the mirror mercilessly on society, reflecting a blood-spattered reality behind the facade of propriety. The institutions of his era – the Bourbon monarchy, the Revolutionary Republic, and the Napoleonic Empire alike – all found cause to censor and cage him. It’s telling that all regimes, no matter their ideology, feared Sade. He was beyond the pale.

And yet, here we are: in modern times, Sade is studied, his complete works published, his perversions fodder for philosophy seminars. What does this mean? It means the knife he wielded cut deep enough that the wound is still open. Some have condemned him as “an incarnation of absolute evil,” others have hailed him as “a champion of total liberation” . Perhaps he is both. But one thing is certain: Sade’s art – if we dare call those horrid visions art – transgressed boundaries that still unsettle us. He revealed a void at the center of the human soul that no dogma can neatly fill. For that, he was silenced in life, and even in death his works remained forbidden fruit for over a century . Only a culture finally ready to question its own values could dig up Sade’s literary corpse and face it. We study him not to emulate his monsters, but to understand the extremes of thought and freedom. He is a reminder that art can be a knife that cuts through every last tether – even the tether of humane restraint. In Sade’s unforgiving ethos, art is not just a knife; it is a guillotine, dropping on the neck of virtue itself. Little wonder the world blinked and looked away for so long.

Five men, five knives, five wounds dealt to the complacency of their ages. Each paid in suffering for the truths he told. Plato nearly enslaved, Ovid exiled, Hallāj tortured to death, Bruno burned alive, Sade imprisoned in silence. Their lives are extreme testimonies to the cost of speaking out, of imagining beyond the permitted. History paints itself as a progression of order and light, but in truth it is written in blood – often the blood of artists and thinkers who cut new paths through the dark. The institutions they defied – Athens’s democracy, Rome’s imperial family, the Abbasid Caliphate, the Roman Church, the French state – are all, in hindsight, revealed as brittle things, fearful of the power that one passionate individual could wield with pen or voice. These institutions were cowards, armoring themselves in dogma and law, yet quaking before the knife of art.

And today? The knife is still in our hands. To wield it is to accept the risk that comes with truth. The censors and inquisitors of our time may not wear togas or turbans or cassocks – they might wear suits, or military fatigues, or the guise of social media mobs – but they remain ever ready to cry heresy, to exile or cancel or crucify (figuratively, if not literally) those who defy the consensus. The names change; the fear of the unsanctioned truth remains. In a world saturated with propaganda and “acceptable” discourse, to create art that truly challenges – that transgresses – is to walk the same road as our five world-shapers. The road is safer now in some places, but the knife still draws blood. Think of the whistleblower, the dissident poet, the persecuted artist in authoritarian lands, the outspoken philosopher attacking sacred cows – they all carry that blade and feel its edge. Not all are as grand or reckless as the men we have discussed, but the principle is the same. As Shelley once observed, “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” The powerful know this, and they hate it.

To wield the knife of art today means refusing to be cowed. It means remembering that art is not merely a mirror to society but a weapon to shape it – or shatter it. It means that sometimes saying “Fuck you” to authority, as crude as that sounds, is the most sacred duty of the artist and the thinker. The alternative is a world declawed and lobotomized, where art is reduced to anesthetic and lies reign unchallenged. Plato, Ovid, Hallāj, Bruno, de Sade – disparate souls from different millennia – are united in a lineage of creative defiance. They remind us that every freedom we enjoy was carved out by someone’s courage to offend, to blaspheme, to break the leash. The knife of art is sharp; in the hand of the brave it cuts openings into new worlds. The challenge before us is whether we will pick it up. Will we choose the obedient comfort of sanctioned truth, or will we grip that bloody handle, carve our own vision, and damn the consequences? The story of civilization is not one of polite conversations – it is, and always has been, a knife fight.

i love my

Art is much more than decoration; it is a craft deeply interwoven with the fabric of society. Throughout history, art has reflected society’s values and beliefs, while also questioning and critiquing them . In this way, art serves as both a mirror and a weapon: it shows us who we are, and it challenges who we think we are allowed to be . Whether through painting, sculpture, music, or performance, artists channel cultural ideals and anxieties into tangible form. Their creations ignite critical thought and public dialogue, often provoking discomfort and introspection . By capturing the spirit of their times or exposing its injustices, artists help society see itself more clearly. Crucially, when an artwork mirrors the world around us, it also has the power to reshape that world by opening eyes and minds.

This dynamic relationship between art and society means that truly impactful art is rarely polite or complacent. On the contrary, meaningful art pushes boundaries. Because society is built on norms—rules about beauty, behavior, and belief—artists inevitably find themselves either upholding those norms or rebelling against them. Many choose rebellion. In fact, the history of modern art is largely a history of creative rebellion, as we will see. When conventions become cages, art breaks free. And when art breaks free, it often transgresses the comfortable limits of society.

Transgression: When Art Breaks the Rules

To transgress means to violate a boundary or norm. In art, transgression has become almost synonymous with innovation and authenticity. The very notion of an “avant-garde” entails stepping beyond what is acceptable or expected. Indeed, transgression – the violation of norms – has been essential to art since at least the 19th century . As one cultural critic notes, “all the ways of defining what an artist is suggests that the artist’s role is to disrupt norms and conventions and to upset people” . In other words, artists are often expected to shock the bourgeoisie, to jolt the public out of complacency . By deliberately offending prevailing tastes or questioning sacred beliefs, artists perform a kind of cultural wake-up slap. This shock can have “beneficially disruptive effects” – destabilizing old certainties and aligning art with movements to upend existing forms of power .

Why does art so often lead to transgression? It may be because wherever there is a rule or a taboo, creativity feels compelled to test it. As theorist Laura Kipnis observes, if you have a church, you will get blasphemy; if you have strict morality, you will get art that revels in the forbidden . Every norm invites its own violation. And so, over time, many artists have made it their mission to cross the line – aesthetically, politically, or morally. In doing so, these transgressive artists have expanded the realm of the possible. They have exposed society’s hypocrisy, challenged authority, and even helped liberate oppressed ideas or groups.

However, breaking rules always comes at a price. Transgressive art often meets censorship or outrage from those who guard the status quo. Many of the artists we will discuss faced scathing criticism, public scandal, or even legal consequences in their time. Yet their willingness to provoke controversy is precisely what makes them influential. By defying the “muggle censorship board of eunuchs” – those timid authorities who would neuter art’s vitality – these artists delivered a stinging slap to censorship itself. In the following sections, we look at several landmark artists and how their acts of creative rebellion were so important in shaping the world we live in today.

Édouard Manet and the Shock of the New

Olympia (1863) by Édouard Manet shocked 19th-century audiences with its frank depiction of a nude prostitute, challenging the era’s moral and artistic norms .

In 1865, French painter Édouard Manet unveiled a painting that would scandalize Paris and herald the birth of modern art. Titled Olympia, it portrayed a completely nude woman (a prostitute, unmistakably) reclining on a bed and gazing brazenly at the viewer. This was not the demure, idealized nude of classical art; this was a real woman, unabashed in her nudity and her profession. When Olympia was exhibited at the Paris Salon, it unleashed a firestorm. Viewers and critics were shocked by both the subject matter – “the sheer nakedness” of the figure – and Manet’s bold style: the painting’s rough brushwork, stark lighting contrasts, and the model’s confrontational stare all violated the polished, modest conventions of the time . As one account describes, Olympia “broke all the unspoken rules about the nude in painting” and married aesthetic shock with moral outrage about gender and class . In short, Manet had transgressed Victorian morality and artistic tradition in one stroke.

Manet had already begun rattling the establishment a couple years earlier. In 1863 his work Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass) was rejected by the official Salon and instead shown in the landmark Salon des Refusés (Exhibition of Rejects) – a show literally created for paintings too scandalous for polite society . In Luncheon on the Grass, Manet depicted a naked woman picnicking casually with two fully clothed men. This indelicate scenario, combined with the woman’s direct gaze at the viewer, shattered conventions of modesty and the academic ideal of the female nude . The public was outraged, yet the painting drew huge crowds. Together, these works by Manet signaled a decisive break from traditional art. They ushered in a new realism that confronted viewers with the truths of modern life – sex, commerce, and individuality – rather than prettified fantasies. Manet’s transgression was the spark that ignited modern art, proving that an artist could defy society’s rules and still achieve immortality. In fact, Manet’s rebellious spirit inspired the next generations of avant-garde artists to keep challenging the status quo . The lesson was clear: to be modern was to be subversive.

It’s worth noting that another Realist painter, Gustave Courbet, pushed the envelope even further around the same time. Courbet’s notorious canvas L’Origine du monde (The Origin of the World, 1866) depicted, with shocking frankness, a close-up of a woman’s genitals. This raw portrayal of female sexuality was so provocative that it was kept hidden in private collections for a century. Even in the 21st century, Courbet’s graphic painting “still has the power to shock and trigger censorship” . In 2011, for example, Facebook infamously banned images of L’Origine du monde from its platform as “obscene,” igniting legal battles over art and free expression . The continuing controversy around this 19th-century painting underlines a key point: when art exposes our most intimate truths, it threatens those who prefer prudish illusions. Courbet and Manet, each in their own way, thrust reality in the face of a hypocritical society – and society, scandalized, eventually had to broaden its mindset.

Marcel Duchamp: Redefining Art Itself

Fountain (1917) by Marcel Duchamp – an ordinary urinal turned on its side – defied every notion of what “art” should be, provoking outrage and a revolution in art theory .

Fast-forward to the early 20th century, and artists were not only transgressing moral codes, but the very definition of art. No one exemplifies this better than Marcel Duchamp, the iconoclastic French artist who in 1917 presented a porcelain urinal as a sculpture titled Fountain. Duchamp’s submission of this signed urinal to an art exhibition was an outrageous prank – and a stroke of genius. The art show had advertised that any work would be accepted from any artist who paid the fee, but when Duchamp (under a pseudonym “R. Mutt”) delivered Fountain, the organizers were aghast and refused to display it . To them, this was not “art” at all but an insult. Duchamp promptly resigned from the board in protest .

Why was Fountain so transgressive? As one contemporary wrote in defense of the piece: “Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it… and created a new thought for that object.” By taking a mass-produced urinal, signing it, and declaring it art, Duchamp attacked the sacred assumption that art must be a beautiful handcrafted object. Fountain was an “assault on the idea that art is [only] concerned with aesthetic beauty and norms” . It boldly challenged the notion that art required traditional craftsmanship or inherent beauty – instead proposing that the artist’s intent and context could transform an everyday object into art . This was an outrageous idea in 1917. Critics sneered; some were deeply offended at what they saw as a joke in poor taste or a nihilistic stunt.

And yet, that urinal changed the course of art history. Duchamp’s unrepentant transgression redefined artistic boundaries and paved the way for conceptual art . By the mid-20th century, the influence of Fountain was everywhere – in Pop Art’s use of mundane objects, in the idea that ideas themselves can be art. The questions Duchamp raised – What is art? Who decides? – permanently expanded society’s understanding of creativity . A century later, Fountain is celebrated as possibly “the most intellectually captivating and challenging art piece of the 20th century” . What was once seen as transgressive nonsense is now hailed as genius. This pattern would repeat again and again: today’s scandal in art often becomes tomorrow’s masterpiece. Duchamp taught us that the artist’s job is sometimes to upend all the rules, even the rules of art itself.

Picasso’s Guernica: Painting as Protest

Not all artistic transgressions are about nudity or rude jokes on the art establishment. Some of the most powerful acts of artistic rebellion have been political, aiming their barbs at governments, wars, and injustice. In 1937, during the dark days of the Spanish Civil War, Pablo Picasso created a mural that shocked viewers in a different way. His painting Guernica portrayed the bombing of a defenseless Spanish town in a chaotic tangle of agonized human and animal forms. Executed in stark black-and-white, Guernica was Picasso’s anguished response to the atrocities of war – a huge anti-war statement at a time when much of the world was still appeasing fascism. This painting violated the norm that art and politics should not mix so bluntly. It was unapologetic propaganda of empathy, forcing the viewer to confront suffering and carnage.

What made Guernica transgressive was partly its modern, fractured style (Cubism) used in service of an overt message, and partly its willingness to depict horror without sugarcoating. As one analysis notes, Guernica “powerfully condemned the atrocities of war without uttering a single word,” using distorted Cubist forms to convey profound anguish . At the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris, where Guernica was displayed, its raw anti-Nazi, anti-war sentiment was both admired and unsettling. The painting soon traveled the world and took on a life as a rallying cry for peace and resistance. It was banned in Francisco Franco’s Spain; later, a tapestry replica at the United Nations was famously covered up when it threatened to embarrass U.S. officials advocating for the Iraq War in 2003. Clearly, Picasso’s masterpiece still has the power to unnerve the powerful.

Guernica’s legacy is that it showed how art can transgress not just aesthetic norms but political ones. In an era of propaganda and doctored narratives, Picasso delivered a slap of truth. He demonstrated that a painting could shake the conscience of the world. Many politically engaged artists have followed suit, from anti-war musicians to dissident painters. When we see graphic images of war in media today or large-scale protest murals, we are witnessing Picasso’s daring influence. He broadened art’s mission, proving that telling an uncomfortable truth is more important than pleasing a gallery. In doing so, he paved the way for all art-as-activism and set a precedent: no tyrant or taboo is too big to take on, if you have a brush or pen in hand.

The Feminist Avant-Garde: Judy Chicago and the Guerrilla Girls

By the late 20th century, transgression in art took on new fronts – including the battle against patriarchy in the art world and society at large. Female artists who had long been marginalized decided to break the silence with confrontational works that some viewed as indecent or outrageous, but which ultimately changed cultural attitudes. A landmark example is Judy Chicago’s installation The Dinner Party (created 1974–1979). This monumental work consisted of a large triangular table with 39 place settings, each dedicated to an important woman from history – and each plate stylized with designs evoking female genitalia (butterfly- or flower-like vulvar forms). In a direct challenge to male-dominated art history, Chicago celebrated women who had been overlooked, in a visual language that unabashedly embraced female sexuality and empowerment . The work was as transgressive as it was groundbreaking. Many critics (mostly male) at the time were scandalized by the frank vaginal imagery and the open feminist agenda. Some derided The Dinner Party as vulgar or crude. Museums were initially hesitant to acquire it, fearing controversy.

Yet over time, this once-outrageous installation has been recognized as a watershed in feminist art. The Dinner Party overtly challenged the male-dominated art canon and traditional narratives , demanding that women’s contributions be literally given a seat at the table of civilization. It also helped normalize imagery and subjects that had been taboo (the female body from a woman’s perspective, menstruation, childbirth, etc.). Chicago and her contemporaries showed that transgression can be a form of correction – by violating prudish sensibilities, they corrected a long history of silencing. Today, The Dinner Party is permanently housed in a museum, and its once-shocking motifs are taught in art schools.

Around the same time, the anonymous collective known as the Guerrilla Girls took another transgressive approach: using guerrilla art tactics to expose sexism and racism in the art establishment. Donning gorilla masks and pasting satirical posters around New York, they posed pointed questions like “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” – noting that less than 5% of the artists in the Met’s modern section were women, but 85% of the nudes were female . This cheeky, subversive campaign embarrassed powerful institutions and was certainly not “proper” by traditional standards. Museum board members were not accustomed to being called out with statistics and humor, especially not by anonymous feminist avengers. The Guerrilla Girls’ poster art was transgressive in form (wild street postering rather than polite critique) and in content (airing the art world’s dirty laundry). By shaming galleries and museums, they forced a public conversation about representation that has reshaped hiring and collecting practices. Decades later, their influence shows in the far greater awareness (if not yet complete resolution) of equity in art. What was once a transgressive stunt is now an institutional mandate: museums today actively work to include more women and artists of color, something due in part to those early feminist truth-bombs.

The feminist art movement proved that transgression can be constructive. By violating decorum – whether through frank imagery or confrontational tactics – these artists opened eyes to injustice. They showed that sometimes you have to offend to enlighten. Society’s understanding of art and gender evolved because a few brave women were willing to be loud, bold, and unapologetically transgressive in their art.

Performance Art and the Body: Marina Abramović

While painters and sculptors were breaking rules on canvas, other artists took rebellion off the pedestal and into real life. In the 1960s and 70s, the rise of performance art brought some of the most visceral transgressions in art history, as artists used their own bodies and endurance as the medium. One of the most notorious performance artists is Marina Abramović, who repeatedly tested the limits of pain, trust, and propriety in her works. Perhaps her most infamous piece was Rhythm 0 (1974), an experiment so extreme it remains shocking decades later.

In Rhythm 0, Abramović stood passively in a gallery for six hours, having placed 72 objects on a table – objects of pleasure and pain – that the audience was invited to use on her however they pleased . Among the items were a rose, a feather, a mirror, but also scissors, chains, a scalpel, and even a loaded pistol with a single bullet . Her only instruction: “I am the object. During this period I take full responsibility.” The performance began tamely, with visitors giving her gentle touches or a rose. But as the hours passed, the atmosphere turned harrowing. According to an art critic who was present, after three hours someone had cut off all her clothes with razor blades; by hour four, those blades were cutting her skin . A man slashed her throat to drink her blood. Various audience members began to molest her body in minor but real ways . The tension reached a climax when an attendee picked up the loaded gun, placed it in Abramović’s hand, and aimed it at her neck — attempting to make her literally pull the trigger on herself . At this point, a fight erupted among audience members, some finally intervening to protect Abramović from the most violent faction . When the 6-hour limit was reached, the artist, bleeding and tears in her eyes, simply began to walk towards the audience. In her later recollection, “Everyone ran away, to escape an actual confrontation” . The crowd, which moments before had felt free to torment her as an object, could not face her as a living person.

This performance was a shattering transgression of the normal relationship between artist and audience, and of social norms around violence, empathy, and consent. Abramović’s piece revealed a chilling truth: given anonymity and freedom from consequences, ordinary people could quickly devolve into oppressors. “What I learned was that […] if you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you,” Abramović said later. “I felt really violated…” . Indeed, Rhythm 0 held up a mirror to the audience’s darkest potentials – a reminder of how thin the veneer of civility can be. Critics at the time said “this is not art, it’s insanity,” disgusted by the spectacle . But in retrospect, the piece stands as a landmark: it erased the boundary between art and life in a terrifying way, proving that art could directly engage (and expose) human psychology. Abramović turned her own body into a canvas of transgression, and by doing so, showed just how far art can go. Today, she is internationally acclaimed, and performance art is a respected genre – but only because artists like her were willing to bleed for it (literally). The transgressive performances of the 70s expanded art’s territory to include human behavior itself. They also raised enduring ethical questions: How far is too far? What do we do when art isn’t safe or pretty? Those questions continue to provoke and inspire new artists in our era.

Culture Wars: Andres Serrano (and the Battle over Censorship)

Artistic transgression hit a raw nerve in the late 1980s in what became known as the American culture wars. During this period, conservative politicians and religious groups fiercely protested certain artworks they deemed offensive, particularly those funded by public money. Two figures became unwitting poster children of “obscene art” in this era: photographer Robert Mapplethorpe and visual artist Andres Serrano. By pushing the limits of sexual and religious subject matter, these artists found themselves at the center of national debates on decency, free expression, and censorship.

Serrano’s work Piss Christ (1987) epitomizes this clash. The piece is a large photograph of a crucifix submerged in a glass tank of the artist’s own urine. Serrano, who was raised Catholic, intended it as a complex statement on the intersection of the sacred and the profane – how commercialism and cheapening of Christian icons might be the real blasphemy. But many did not care for such nuance when the photo went on exhibit. Once news got out that this artwork – considered by some to be nothing short of sacrilege – had received a small grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), outrage exploded. Politicians fulminated about taxpayer-funded blasphemy; conservative pundits called Serrano everything from degenerate to evil. There were immediate attempts at censorship, calls to remove the piece from galleries and to revoke arts funding . Serrano even received death threats. As one account dryly notes, “Naturally, there was vast outrage and attempts at censorship” after Piss Christ’s release . The artwork was vandalized multiple times by protesters in Australia and Europe.

Instead of folding, many art institutions and artists stood by Serrano’s right to offend. Museums defended the artistic merit of Piss Christ and, in some cases, literally kept the lights on the piece despite threats . This, of course, only fueled conservative anger. The U.S. Senate held hearings about NEA grants, and famous senators like Jesse Helms fulminated that such artworks were proof of moral rot. Around the same time, Robert Mapplethorpe’s traveling photography exhibit – which included homoerotic images and nude children – was canceled by one museum and then led to an obscenity trial at another. In 1990, the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati and its director were actually brought to trial on charges of obscenity for exhibiting Mapplethorpe’s photos . (They were eventually acquitted by the jury, a landmark victory for artistic freedom .) These incidents marked the first time art itself was put on trial in America’s courts, and they became a battleground over how far free expression could go.

The irony is that all the attempted censorship vastly amplified the reach of these artworks. Piss Christ and Mapplethorpe’s photographs, which might have been quietly noted in art circles, instead became front-page news and subjects of nationwide discourse. By trying to suppress transgressive art, the would-be censors only underlined its importance. The late ‘80s culture wars ultimately led to changes (some funding restrictions for the NEA, for instance), but they also proved that art could defeat censorship. The Smithsonian Magazine later noted that the Mapplethorpe trial “changed perceptions of public funding of art” and that its reverberations “never really go away” . In the court of public opinion, the arts community rallied, framing the controversy as not just about one crucifix in urine or one BDSM photo, but about the First Amendment and the necessity of artistic freedom. By the 1990s, “controversial” art was practically chic; transgression had become a badge of honor among serious artists, precisely because it meant your work had touched a nerve.

Today, Serrano’s Piss Christ is taught in textbooks as a prime example of late 20th-century art controversy. What was once reviled as blasphemy is now protected as expression (even if it still offends some). The furor over Piss Christ also opened up a broader public conversation about how art can challenge religion, authority, and public sensibilities. It demonstrated that art still matters enough to fight over. And importantly, the art world’s defense of works like Serrano’s sent a message to the “censorship boards” of the world: artists will not be cowed by puritanical outrage. The only path is forward, into freer and bolder territory.

Street Art Revolution: Banksy’s Guerrilla Commentary

Rage, the Flower Thrower (2003) by the anonymous street artist Banksy uses graffiti in the West Bank to transgress political boundaries and provoke dialogue, turning vandalism into a powerful form of art.

In the 21st century, one of the most visible forms of artistic transgression has literally been splashed across city walls worldwide. We’re talking about street art – graffiti, murals, and other unsanctioned art that appears in public spaces without permission. For decades graffiti was considered a crime or a blight by authorities (and still is in many cases). But artists transformed it into a rebellious art movement that challenges both the law and the elite art world. No figure embodies this more than the pseudonymous provocateur Banksy.

Hailing from the UK, Banksy gained fame (or infamy) through bold stencil graffiti that would mysteriously appear overnight on buildings from London to Bethlehem. These images often carry scathing social or political messages, delivered with wit and dark humor. For example, Banksy’s iconic stencil of a protester hurling not a Molotov cocktail but a bouquet of flowers – known as Flower Thrower or Love Is In The Air – appeared on a West Bank wall, instantly resonating as a symbol of peace amid conflict. Another mural depicted a young girl frisking a soldier; yet another showed a hole in the wall revealing a paradise beyond, painted on the separation barrier in Palestine. Each piece is a transgression not only of property laws but of political decorum. Banksy’s art boldly exposes issues like capitalism, consumerism, and inequality, forcing passersby to confront uncomfortable truths about society . By placing biting satire in broad daylight, he circumvents the filters of galleries and governments. In fact, Banksy’s work is illegal in most cases – it’s defacement in the eyes of the law – and that is part of its power. The medium is the message: If the authorities don’t like it, maybe they should ask why it speaks to so many people.

Banksy’s anonymous, unsanctioned practice was highly transgressive in the art context of the early 2000s. Galleries didn’t know what to do with a vandal who wouldn’t reveal his identity, yet whose work was gaining a cult following. Over time, the establishment ironically embraced him (his pieces now sell for millions when removed from walls), but he continues to poke fun at that very establishment. In one memorable 2018 stunt, a framed Banksy painting (Girl with Balloon) self-destructed through a hidden shredder moments after being auctioned for over £1 million – a literal slap in the face to art market pretensions, delivered in front of a shocked elite audience. Banksy has also staged “exhibitions” without permission, like placing his own fake artworks in the Louvre and other museums as pranks. Each act is a transgression against authority and profit motives – and each reinforces his anti-establishment message.

The influence of this street art rebellion is vast. Banksy inspired countless artists worldwide to take to the streets with spray cans and stencils, using public art as social commentary. Murals addressing racism, police brutality, climate change, and more now adorn cityscapes, often to the chagrin of conservative leaders but the delight of communities. What was once derided as graffiti vandalism is increasingly recognized as urban art that can rejuvenate and speak for the people. Cities that once arrested street artists now invite them to create murals, acknowledging the form’s impact. This is a direct result of transgressors like Banksy proving that sometimes illegal art is more authentic and relevant than sanctioned art. By bypassing censorship and bureaucracy, street art reaches people directly – and in doing so, it democratizes art and activism. The next time you see a provocative mural on a city wall and feel your mind expand a little, thank the bold graffiti writers who risked arrest to bring art to the streets. They proved that true art doesn’t ask for permission.

Ai Weiwei: Art as Dissent in the Modern Era

Transgressive art is not only a Western phenomenon, nor is it confined to cultural critiques; it can directly challenge authoritarian power at great personal risk. A striking example in our contemporary world is Ai Weiwei, the Chinese artist and activist whose work and life blur the line between art and political dissent. Ai Weiwei has used sculpture, installation, photography, and social media as tools to expose government corruption, champion human rights, and memorialize victims – actions that have put him in direct confrontation with the Chinese Communist state.

One of Ai’s early notorious works, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), consisted of a series of three photographs showing him holding a 2,000-year-old ceremonial urn, releasing it, and watching it smash to pieces. This act was brazenly transgressive on multiple levels: culturally (destroying a precious artifact of China’s heritage) and politically (implying a rejection of the values the state chooses to venerate). The piece sparked outrage and debate in China about the value of history and who gets to decide what should be preserved . As art writer Barbara Pollack noted, Ai turned the ancient urn into what he called a “cultural readymade,” repurposing it to critique the authorities’ narrative of history . Implicitly, Ai was asking: What is more sacred – objects behind museum glass, or freedom of expression? The Chinese government, unsurprisingly, was not amused.

Ai Weiwei continued to transgress boundaries with works like his installation of 100 million hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds spread across a floor at the Tate Modern in 2010 – inviting viewers to literally walk over what symbolized the Chinese populace, a comment on individuality versus the masses under a regime . He also created works directly memorializing those who died due to government negligence, such as the Remembering project (a display of children’s backpacks after the Sichuan earthquake) which implicitly blamed shoddy state construction for school collapses. Ai’s art is often simple in form but loaded in context, and he pairs it with outspokenness on blogs and interviews. This made him a target: in 2011, Chinese authorities arrested Ai Weiwei, held him in secret detention for 81 days, and later continued to harass and surveil him.

Yet even under threat, Ai Weiwei did not back down. Every attempt to silence him only amplified his voice on the global stage. He would tweet criticisms of censorship, create artworks about his detention (e.g., sculptures recreating scenes from his imprisonment), and continue to call out abuses. In essence, Ai Weiwei turned his life into an artwork of resistance. His transgressions – from smashing ancient art to openly defying a repressive government – have inspired people worldwide. In China, he emboldened a new generation of creatives and activists to push back against fear. Internationally, he became a symbol of artistic courage, a reminder that art can indeed threaten the powerful.

The world we live in has been partly shaped by Ai Weiwei’s fearless example. Museums and galleries in free countries now more readily present politically charged works, even about China, which they might have shied away from before. Human rights organizations embrace artists as allies. And the conversation about the responsibility of artists to speak truth to power has gotten louder, thanks to Ai and others like him. This is the legacy of transgression: every time an artist crosses a line that was drawn to keep critique out, they widen the space for all of us to question and to demand better from our leaders.

Conclusion: Legacy of the Rule-Breakers

Looking back at these diverse artists – from Manet’s shockingly naked Olympia, to Duchamp’s cheeky urinal, to Picasso’s anguished protest, to the feminists, performers, street iconoclasts and activist dissidents – a clear pattern emerges. Transgression in art is not a tangent to the story of culture; it is the story of culture moving forward. Each act of artistic rebellion we discussed was like a battering ram against the walls of prejudice, ignorance, or complacency. By breaking the rules of their day, these artists expanded what future generations could see, say, and imagine. The scandalous art of yesterday becomes the accepted classic of today – and paves the way for the new rebels of tomorrow.

Crucially, many of these artists dealt serious blows to the forces of censorship and repression. Their work, in effect, was a big slap in the face to what our user colorfully called the “muggle censorship board of eunuchs” – those who lack the courage or vision to embrace freedom of expression. Time and again, the prudes and censors tried to snuff out the flame of transgressive art, only to find that ideas cannot be so easily silenced. After all, art is an expression of human freedom; to stifle it is to stifle the human spirit itself. And as these stories show, the human spirit is irrepressible.

Thanks to these bold creators, we now live in a world where art is far less confined. Museums proudly display works that once caused riots. Governments (in many places) fund art that critiques them. Galleries include women and minority artists who were once excluded. Street murals that would have been immediately scrubbed off are now preserved as cultural heritage. None of this came easily – it was fought for by artists who suffered ridicule, imprisonment, or worse. We owe a great debt to the transgressors. They made our societies more open, our perspectives broader, and our capacity for empathy deeper.

Of course, the struggle between artistic freedom and censorship is not over. Even today, there are calls to remove artworks that offend, regimes that jail artists for speaking out, and social media “community standards” that sometimes echo old prudish norms (as we saw with Facebook censoring Courbet’s painting). Every generation will have its new line to cross. But if history is any guide, the artists will be there – brush or camera or code in hand – ready to cross it. They will scandalize the comfortable and comfort the scandalized, challenge authority and champion the marginalized. And in doing so, they will continue to shape the world.

So, here’s to the rule-breakers: the Manets, Duchamps, Picassos, Chicagos, Abramovićs, Serranos, Banksys, Ai Weiweis, and countless others who have dared to create unflinching art. They remind us that crafting art is inherently a radical act. To create is to assert one’s voice, one’s vision – sometimes against the grain of society. And when that vision is true and needed, no amount of censorship can hold it back forever. What was once transgressive becomes transformative. The shock of today becomes the enlightenment of tomorrow. The eunuchs of the censorship board may clutch their pearls, but ultimately, they are powerless against the fearless creativity of artists. The world marches forward, led often by those who dare to imagine it differently. As the saying goes, “art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.” The artists we’ve discussed did exactly that – and we are freer, wiser, and better off because of it.

Sources:

Adeleke, Kazeem. “How Art Challenges Social Norms: A Bold History of Creative Disruption.” ARTCENTRON, 25 Aug 2025 . Kipnis, Laura. “The Art of Transgression.” EXPeditions, 14 Jun 2025 . Cronan, Todd. “The Uses and Abuses of Manet’s Olympia.” Jacobin, 16 Oct 2024 . L’Origine du monde – Wikipedia . Mann, Jon. “How Duchamp’s Urinal Changed Art Forever.” Artsy, 9 May 2017 . “Early 20th Century: The Avant-Garde and Artistic Convention.” ARTCENTRON . “Breaking Boundaries with Visual Expression.” ARTCENTRON . “Feminist Art Movements: Dismantling Patriarchal Structures.” ARTCENTRON . “Chinese Contemporary Art: Challenging Authoritarianism.” ARTCENTRON . Abramović, Marina – Rhythm 0 – Wikipedia . Hessel, Katy. “Marina Abramović’s shocking Rhythm 0 performance shows why we still cannot trust people in power.” The Guardian, 25 Sep 2023 . Palmer, Alex. “When Art Fought the Law and the Art Won.” Smithsonian Magazine, 2 Oct 2015 .