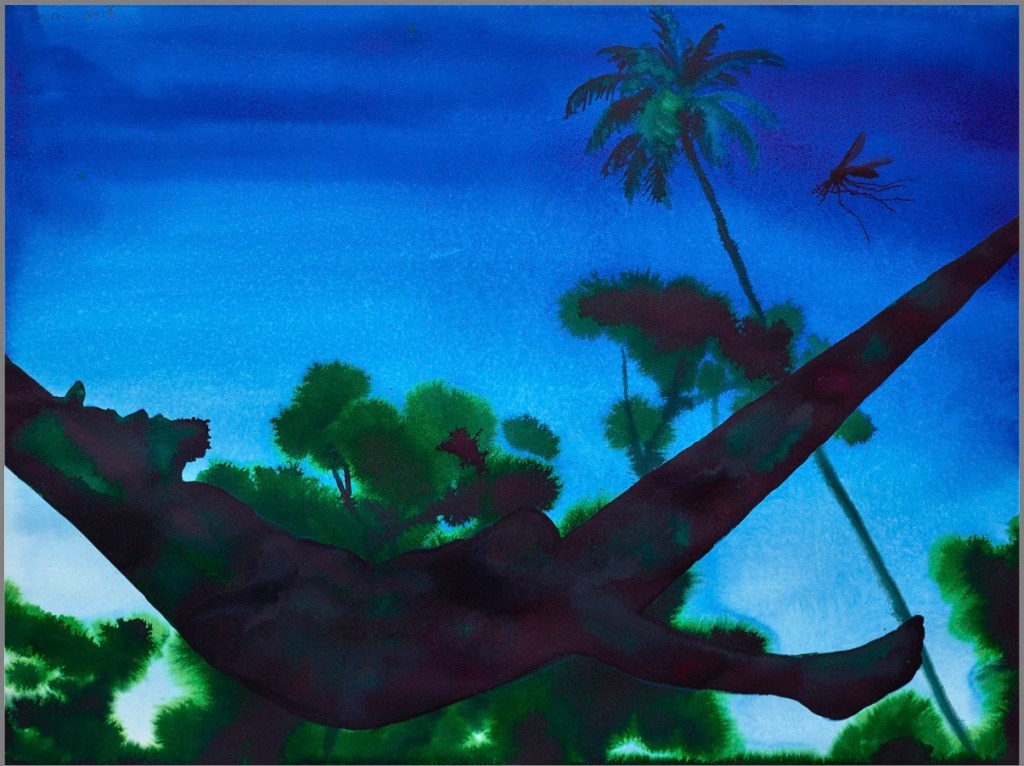

Each era bequeaths two intertwined relics: the mute sediment of events themselves and the interpretive scaffolds later raised upon that mute ground. The chapters that follow braid three such relics to expose how meaning coagulates, dissolves, and coagulates again. First, a Deuteronomistic lawsuit recasts Israel’s flirtation with foreign cults as juridical rupture; second, a Shilonite mother’s hymn overturns social gradients through divine inversion; third, a contemporary watercolor suspends a reclining figure in tropical stillness already menaced by an insect’s whisper. Read together, they form a stratified palimpsest: philological fossils—Akkadian šēdu, proto-North-West Semitic ṣûr, archaic Hebrew hiphil cadences—index ancient chains of borrowing, while historiographical cross-sections reveal how seventh-century editors, post-exilic theologians, and modern painters translate raw contingency into legible order. What threads these disparate media is the pulse between centripetal consolidation and centrifugal dispersion, the symbiotic rhythm earlier essays designate omicron and omega. Omicron signals outward drift, the proliferation of variance; omega names the magnetic pull toward coherence, gravitation, and binding gravitas. Covenant law crystallizes tribal memory beneath omega’s compressive weight, yet Hannah’s barren lament blooms into royal legitimation by riding omicron’s expansive thrust. Likewise, the watercolor’s hammock—momentarily weightless in viridian canopy—evokes omega’s repose, even as the hovering mosquito portends omicron’s disruptive sting. Historical consciousness itself, therefore, emerges as the oscillating ledger of these two vectors: binding gravity and eruptive plurality negotiating the terms of every remembered moment. The letters ahead invite the reader to perceive doctrinal rock, maternal psalm, and trembling pigment bloom as simultaneous witnesses to preservation and revision. Each artefact is both anchor and wake, evidence that no narrative finalizes the past, no ledger closes its accounts. Instead, every chapter opens onto the horizon where omicron’s centrifugal sweep and omega’s consolidating fold meet, entwine, and recommence their dialogue—a dialectical ledger in ceaseless composition.

“The past may be distinguished from history, for the latter is an account of the former.” The aphorism divides raw temporality from its narrative capture: the past is sheer occurrence—contingent, mute, irretrievable in itself—whereas history is the discursive labor that renders those occurrences legible by selecting, ordering, and framing them. Etymologically, past (Latin praeteritus, ‘that which has gone beyond’) signals elapsed duration, while history (Greek historia, ‘inquiry, learned account’) already presupposes a witness who gathers and recounts evidence; the interval between the two terms therefore measures the distance from event to exposition. Historiographically, modern critical method—rankean source-critique through Annales longue durée—has progressively underscored that every historical synthesis rests on choices of scale, archive, and concept, so that “the latter” is never a transparent mirror but a constructed perspective conditioned by ideology, genre, and available records. In terms of historicity, the sentence reminds us that what once merely happened acquires meaning only when folded into a story, yet each story, being situated, can be revised, supplanted, or silenced: the archive is dynamic, and the past remains inexhaustible to any single historiographical act.

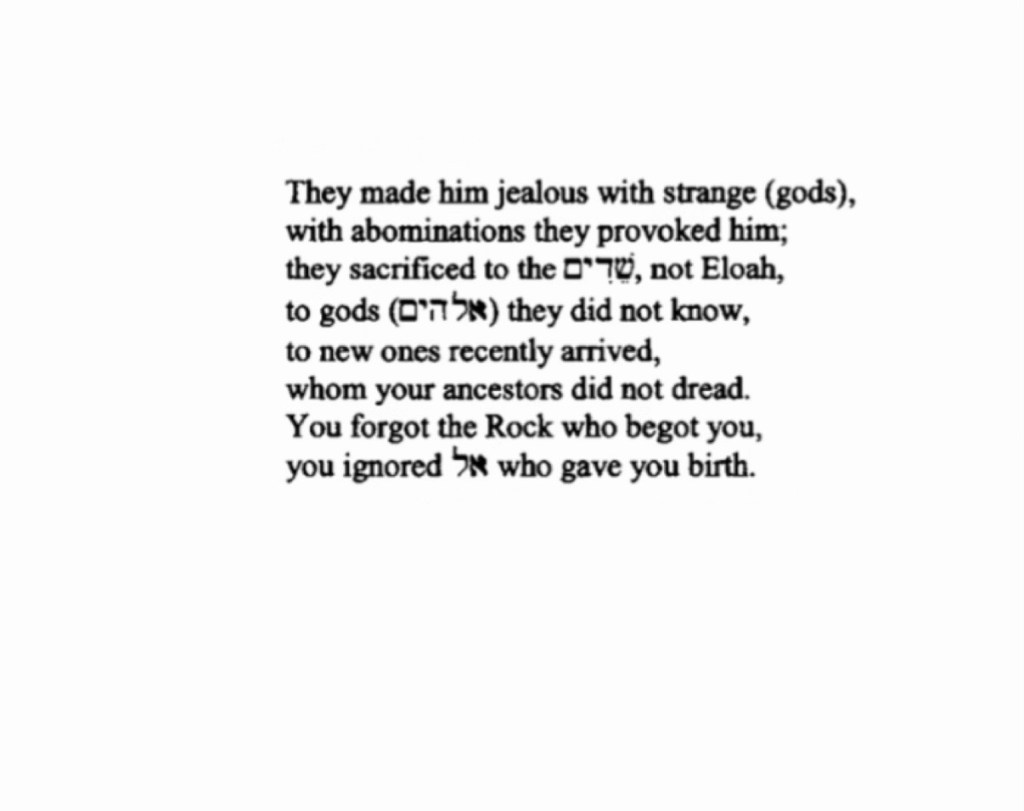

In the Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32 : 16-18), the poet indicts Israel for cultic infidelity: “They made him jealous with strange gods; with abominations they provoked him. They sacrificed to the šēdîm, not to ʾĒlōah, to gods (ʾĕlōhîm) they had never known, to newcomers lately come, whom the ancestors never feared. They forgot the Rock who begot them; they neglected ʾĒl who gave them birth.” The Hebrew verbs bristle with forensic force—qinnēʾu (“they provoked jealousy”) and tăʿăbû (“they made abominable”)—so that idolatry becomes a juridical breach of covenant rather than a mere ritual error. Etymology sharpens the charge. Šēdîm (שֵּׁדִים) is a rare plural of šēd, a loanword cognate with Akkadian šēdu for a protective or malevolent spirit; by invoking it here, the poet reduces rival deities to foreign daemons. ʾĒlōah is the archaic singular of ʾĕlōhîm, preserving the north-west Semitic root ʾ-l “mighty,” while ʾĒl alone evokes both the earliest Canaanite sky-god and the primordial divine epithet assimilated by Israelite theology. Thus the verse contrasts the transient novelty of imported powers with the generative stability of the primordial Rock (ṣûr), itself a martial-geological metaphor for unassailable source. Historically, the passage crystallizes the Deuteronomistic polemic of the late seventh to early sixth century BCE, when Josianic and exilic editors recast older tribal hymns to enforce Yahwistic centralization and to interpret national catastrophe as theologically warranted. By distinguishing the past arrival of alien cults from the ancestral knowledge of the Rock, the poet embeds a charter myth of apostasy and return: every deviation into syncretism is already anticipated as a forgetting of birth, and every future reform imagines itself as anamnesis of that primal begetting.

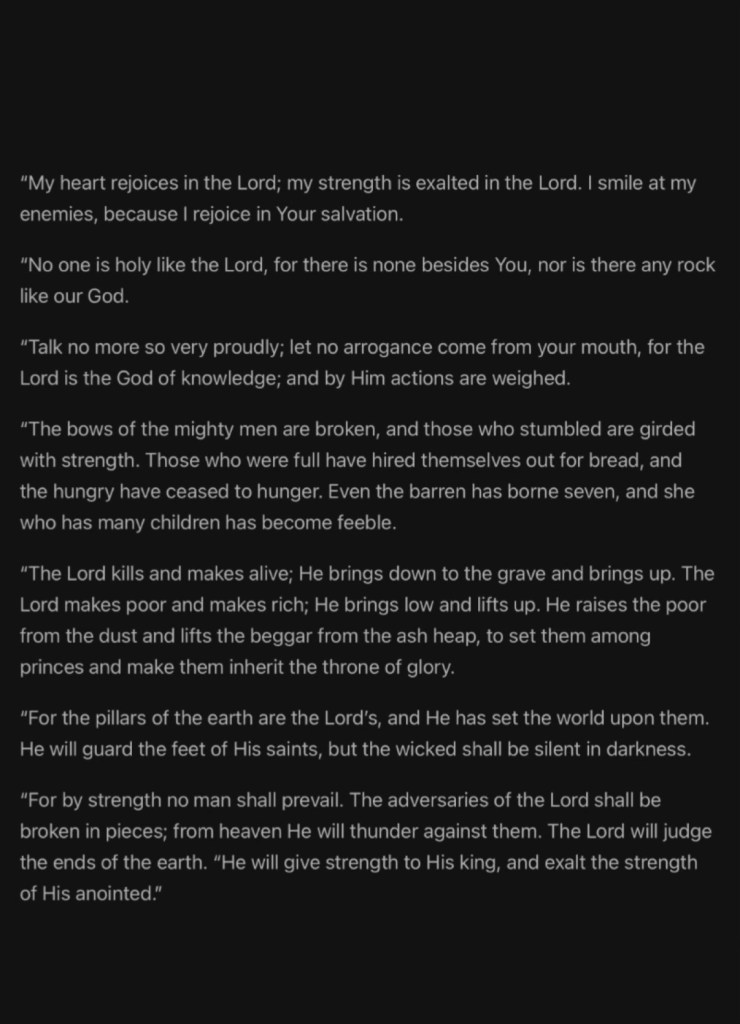

Hannah’s canticle in 1 Samuel 2 : 1-10 stands at the hinge between the tribal epoch and the rise of kingship, portraying personal deliverance as a template for national reordering. The song opens with a jubilant inversion: “My heart rejoices in the Lord; my horn is exalted in the Lord” (šāś libbî… rāmā qarnî). Libbî (“my heart”) names not emotion but the seat of deliberation, while qeren (“horn”) is a zoological metonym for power publicly manifested; together they voice a consciousness both interiorly persuaded and outwardly empowered. The verbal root ʿly (“to exalt, raise high”) anticipates the poem’s leitmotif of vertical reversal whereby social altitudes are upended by divine prerogative. The second movement, “No one is holy like the Lord… there is no rock like our God,” triangulates holiness, uniqueness, and immovability. Qādôš (“holy”) connotes ontological set-apartness, and ṣûr (“rock”) reprises the Deuteronomistic metaphor for the primordial giver of stability encountered in Deuteronomy 32. Etymologically, ṣûr stems from a root meaning “to bind, constrict,” evoking the tectonic compression that forms bedrock; thus the image fuses unyielding solidity with generative pressure. By aligning Yahweh’s transcendence (qādôš) with His geological immanence (ṣûr), the poet collapses the vertical gap between heaven and earth into a single organising axis along which fortunes are redistributed. A series of antithetic colon pairs then dramatises that redistribution: warrior bows shatter while the feeble gird themselves with strength; the sated must hire out for bread while the starving cease to hunger; the barren woman bears seven whereas the prolific mother languishes. Each contrast hinges on verbs of divine causation (šāḇar, ḥālaṣ, rāʿeb, ḥadal, yālad) that overwrite natural expectation with covenantal calculus. Historiographically, such language resonates with late pre-exilic wisdom that evaluated social hierarchy through Yahweh’s ethical sovereignty, yet many scholars detect archaic traits—archaisms like mēʿīl (“bowel, inward parts”) and archaic parallelism—that suggest an older hymn adapted by Deuteronomistic redactors. The text therefore bears the palimpsest of transmission: a nucleus of early Israelite praise, perhaps sung at Shiloh’s sanctuary, reframed to legitimise the forthcoming monarchy Samuel will inaugurate. Verses 6-8 articulate the theology of life and death in concentric antinomies: “The Lord kills and makes alive; He brings down to Sheol and raises up… makes poor and makes rich… brings low and lifts up.” The accumulation of hiphil forms (meḥayyēh, môrîḏ, māʿašîr) underscores active causality, negating any autonomous sphere of fate. Etymology sharpens the claim: Sheʾôl is likely a loan from Akkadian šʾilu, “the underworld cavity,” so Yahweh’s jurisdiction extends even into Mesopotamian conceptual terrain, asserting polemical supremacy over regional death-deities. The climactic image of lifting the beggar from the ʾašpôt (“dunghill, ash heap”) to sit among princes literalises the socio-economic inversion encoded in the covenant law’s concern for widow, orphan, and stranger. The closing doxology, “For the pillars of the earth are the Lord’s… He will give strength to His king,” retrospectively interprets cosmic architecture as the guarantor of political order. Môtzqê (“pillars”) derives from ʿmṣ (“to support, be firm”), suggesting that the earth’s very stanchions are procured by Yahweh’s creative fiat. Historically, the explicit anticipation of a king (melek) within a pre-monarchic narrative frame signals the redactor’s horizon: Samuel’s prophetic career will legitimate Saul and then David, fulfilling this proleptic blessing. By embedding royal ideology inside a maternal thanksgiving, the compiler binds the legitimacy of the crown to the vindication of the marginal, thereby enshrining a dialectic between exaltation and humility that will haunt Israel’s subsequent political theology. In this way Hannah’s song becomes both historiographical overture and perennial liturgical script, encoding a vision in which every ascent to power remains accountable to the primordial Rock who reverses fortunes and remembers the forgotten.

A broad diagonal silhouette bisects the lower half of the sheet, reading as a recumbent figure suspended in a taut hammock whose fabric is rendered in the same near-black wash as the body. The negative space around the form implies slack legs and an up-tilted chin, but no internal features break the silhouette; the eye infers anatomy only from the crisp perimeter where the wash meets the white paper. Inflections of viridian and alizarin emerge where the pigment pools, creating marbled undertones that keep the darkness from flattening into a single value.

The setting is a humid canopy rendered in wet-on-wet watercolor: domed clumps of foliage bloom outward where sap-green was allowed to bleed into cobalt. Against this vegetal softness, a lone palm trunk rises almost vertical along the right third of the composition, its fronds spattered with dry-brush strokes so that each leaflet tapers to a granular point. Dense cyan at the zenith grades toward a milky turquoise near the horizon, implying equatorial noon without a discrete sun; subtle back-runs and tide marks record the watercolor’s evaporation and anchor the image in its own material process. A single insect—mosquito-scaled but dragonfly-limbed—hovers near the palm crown, defined by a few decisive strokes of sepia that leave the wings translucent. Its placement above the hammock invites a triangular reading: dormant human, indifferent jungle, predatory vector. Scale is intentionally ambiguous; the insect could be inches from the viewer or improbably gigantic, an ambiguity reinforced by the flat silhouette that denies depth cues within the foreground figure. The piece balances repose and latent threat. Weightless suspension suggests tropical leisure, yet the hammock’s dark tonality veers toward bruise-purple, tinting rest with unease. The insect’s implied whine enters the viewer’s auditory imagination, puncturing the quiet scene and recalling the ecological fact that stillness in a rainforest is provisional, always conditional on unseen hosts. Formally, the composition depends on countervailing diagonals—the hammock, the palm, the insect’s flight path—so that even in apparent languor the eye remains in constant motion. Technique reinforces theme: watercolor’s capillary migrations create halos around foliage and faint blooms in the sky, simulating moisture-laden air; meanwhile the figure, executed in a single loaded stroke, behaves more like ink, resisting diffusion and thus reading as other, alien to the environment that envelops it. This chromatic isolation turns the sleeper into both participant and intruder, a dark island adrift in photosynthetic blaze. The image therefore stages a silent dialectic between vulnerability and dominion, ease and exposure, captured in one suspended noon-hour above a dripping forest floor. The aphorism that “the past may be distinguished from history, for the latter is an account of the former” establishes a conceptual fulcrum on which every subsequent image and text turns. Past—from Latin praeteritus, “having gone by”—signifies raw elapsed actuality, mute and irretrievable; history—Greek historia, “enquiry, learned narrative”—designates the crafted discourse that selects, orders, and interprets those occurrences. The shift from sheer event to narrated meaning thus marks a transit from silence to speech, from contingency to pattern. Each work examined thereafter—Deuteronomy’s covenant lawsuit, Hannah’s canticle of reversal, and the watercolor tableau of a suspended sleeper—performs that same translation, converting lived or imagined moments into emblematic statements about divine, social, and ecological order. Deuteronomy 32:16-18 frames apostasy as a betrayal of origins. The rare plural šēdîm (שֵּׁדִים) demotes rival deities to demonic interlopers, while the singular ʾĒlōah and the archaic epithet ṣûr (“Rock”) recall the primordial giver of stability. Historigraphically, the passage belongs to the late seventh- or early sixth-century redactors who, amid impending exile, re-catalogued national disaster as the legal consequence of infidelity. Yet the diction preserves earlier strata: the loanword šēd from Akkadian šēdu and the Canaanite title ʾĒl testify to an archipelago of religious memories beneath the Deuteronomistic surface. Historicity therefore lies not in a single layer but in the palimpsest of competing addresses to the divine—each re-inscription both preserving and overwriting what came before, just as history overwrites the past while keeping its spectral outline. Hannah’s song in 1 Samuel 2:1-10 elaborates a theology of inversion that mirrors and extends Deuteronomy’s polemic. The heart (lēb) rejoices, the horn (qeren) rises, and barren soil suddenly germinates; bows break while feeble arms cinch new strength. The vocabulary of up-and-down—ʿly, môriḏ, meḥayyēh—transforms vertical space into a moral gradient patrolled by Yahweh. The text’s oldest core, perhaps a tribal hymn from Shiloh, passes through Deuteronomistic hands that insert the proleptic blessing of kingship: “He will give strength to his king.” Here, history not only recounts but anticipates the future, embedding political legitimation in a maternal thanksgiving. Etymology sharpens the inversion: ʾašpôt (“ash-heap”) shares roots with desolation, so the beggar’s elevation to princely status rewrites waste into worth, dust into dynasty. The past event of Hannah’s private deliverance becomes history’s charter for Israel’s coming monarchy, yielding a template wherein every ascent to power must answer to the ex nihilo generosity of the Rock. The contemporary watercolor of a figure reclining in a hammock stages these theological arcs within a secular ecology. The hammock’s silhouette, stroked in bruise-toned washes of phthalo green and alizarin, bisects the sheet like a dark river of embodied repose, while capillary blooms in the surrounding foliage simulate the photosynthetic exuberance of a rainforest noon. A lone mosquito-dragonfly hovers, its scale purposefully indeterminate, conjuring the latent threat that even paradise carries. The painting thus dramatizes the same dialectic as the biblical songs: suspension and vulnerability, leisure and looming inversion. Chromatically, the near-black of the hammock refuses the diffusive luminosity of the greens and blues, echoing Hannah’s contrast between ash-heap and throne; semantically, the insect’s potential sting recalls the šēdîm whom Israel once courted, a reminder that foreign vectors infiltrate the garden under many guises. The artwork becomes a modern midrash on Deuteronomy’s warning and Samuel’s promise: comfort is provisional, vigilance perennial, and each equilibrium awaits its turning. Across these materials, a single structural logic emerges. First, a state of apparent stability—ancestral covenant, personal barrenness, tropical repose—is named. Second, an incursion unsettles that equilibrium—strange gods, social dereliction, the whine of a hovering pest. Third, a narrative response—legal indictment, prophetic song, aesthetic composition—translates rupture into intelligible order. The movement from past disruption to historical articulation enacts what might be called the Mass-Omega/Omicron dynamic: coherence sought after divergence, closure haunted by possibility. Yet the synthesis remains open-ended; history, like watercolor, dries in unpredictable tide marks, leaving stains that testify to forces no single account can fully domesticate. Thus, from an aphorism on the nature of historiography to ancient Hebrew poetry and a twenty-first-century painting, each artifact rehearses the same metaphysical rhythm: event, breach, narration. Together they argue that meaning is neither given nor static but forged in the continuing labour of recollection—an ever-evolving ledger where rocks sing, wombs unlock, and even a hanging hammock whispers the fragile terms of existence.

Epilogue—etymologically the epílogos, the “added word” that seals a discourse—must itself demonstrate how every sealing is provisional, for the narrative arc traced from Israel’s covenant breaches through Hannah’s subversive hymn to the modern watercolor’s suspended quiet shows that each seeming terminus is only the pause between successive drafts of being. Historiographically, the Deuteronomistic editors who reframed ancestral songs into legal indictments and monarchic prophecies exemplify narrative centripetalism: fragments of tribal memory are pulled inward, fused into a unified explanatory core that could stabilize a people staring into exile. Yet the very survival of archaic loanwords—šēdîm from Akkadian spirit-lore, ṣûr from a proto-North-West Semitic geology of divinity—attests to centrifugal residue: divergent, half-erased voices that continue to vibrate beneath the editor’s polished veneer. Hannah’s canticle extends the pattern, presenting the womb as an engine of radical re-ranking—barrenness inverted to plenitude, ash-heap to diadem—thereby coding biological marginality as the site from which social realignments erupt. In the rainforest vignette, the hammock’s opaque silhouette embodies the same oscillation: a momentary enclave of leisure held aloft amid capillary blooms that confess the paper’s own caprice, while the hovering insect foretells inevitable disturbance. Collectively these works chart a pendulum between centripetal integration—rock-solid ancestry, enthronement, pictorial composure—and centrifugal dispersion—daemonized gods, upended hierarchies, eco-threat. Solidity and Possibility thus appear not as binaries but as alternating phases in a single anxious circuit, a cosmic respiration in which the past thickens only to exhale again into reach out. Historicity, therefore, resides in the dynamic ledger that records this desperation: each inscription an attempted settlement, each palimpsest a reminder that the ledger is alive, subject to fresh annotations by future exiles, future mothers of kings, future painters of suspended afternoons. The past never ceases to spill beyond the banks of history; what endures is the labor of staking new weirs, redirecting the torrent into successive channels of meaning, knowing all the while that every epilogue is merely the latest lock-gate in a river still running toward horizons unreached yet.