The Mass-Omicron Framework in the Context of the Big Bang

Baking a Universe from Scratch

Imagine trying to bake a universe the way you would bake a loaf of bread. In baking, you start with a dense little ball of dough and, given warmth and time, it rises and expands. The Big Bang, in a loose analogy, is like that initial dense “cosmic dough” suddenly rising into the enormous loaf of the observable universe. Just as raisins in rising bread move apart as the dough expands, galaxies in our universe drift away from each other as space itself stretches. This baking analogy helps us picture how an incredibly compact beginning can lead to an expansive, structured cosmos. It sets the stage for the Mass-Omicron framework, which tries to understand that initial “dough” of the universe in terms of quantum waves and distributions rather than an intractable point of infinite density.

But how do we quantify or describe that primordial dough-like state of the cosmos? In standard cosmology, the Big Bang often points to a singularity – a single point of infinite density and zero volume. However, infinities like that are troublesome; they’re the mathematical equivalent of dough that weighs infinite kilograms – not exactly a recipe we can make physical sense of. The Mass-Omicron framework is an attempt to reinterpret the Big Bang’s initial state in a more manageable way. Rather than treating all the mass-energy of the universe as squeezed into an actual point (which gives infinite density), we consider it as a wavefunction or distribution spread out in space – albeit extremely peaked and compact. In other words, we replace the idea of an infinite-density singularity with a wave-like description that captures the essence of that concentrated mass without the infinities, much like using a very dense lump of dough instead of an infinitely small point. This approach preserves the narrative toneof baking – mixing and spreading ingredients (or mass-energy) – but backs it with the intellectual rigor of mathematics and quantum theory.

The Mass-Omicron Concept: A Wavefunction Perspective

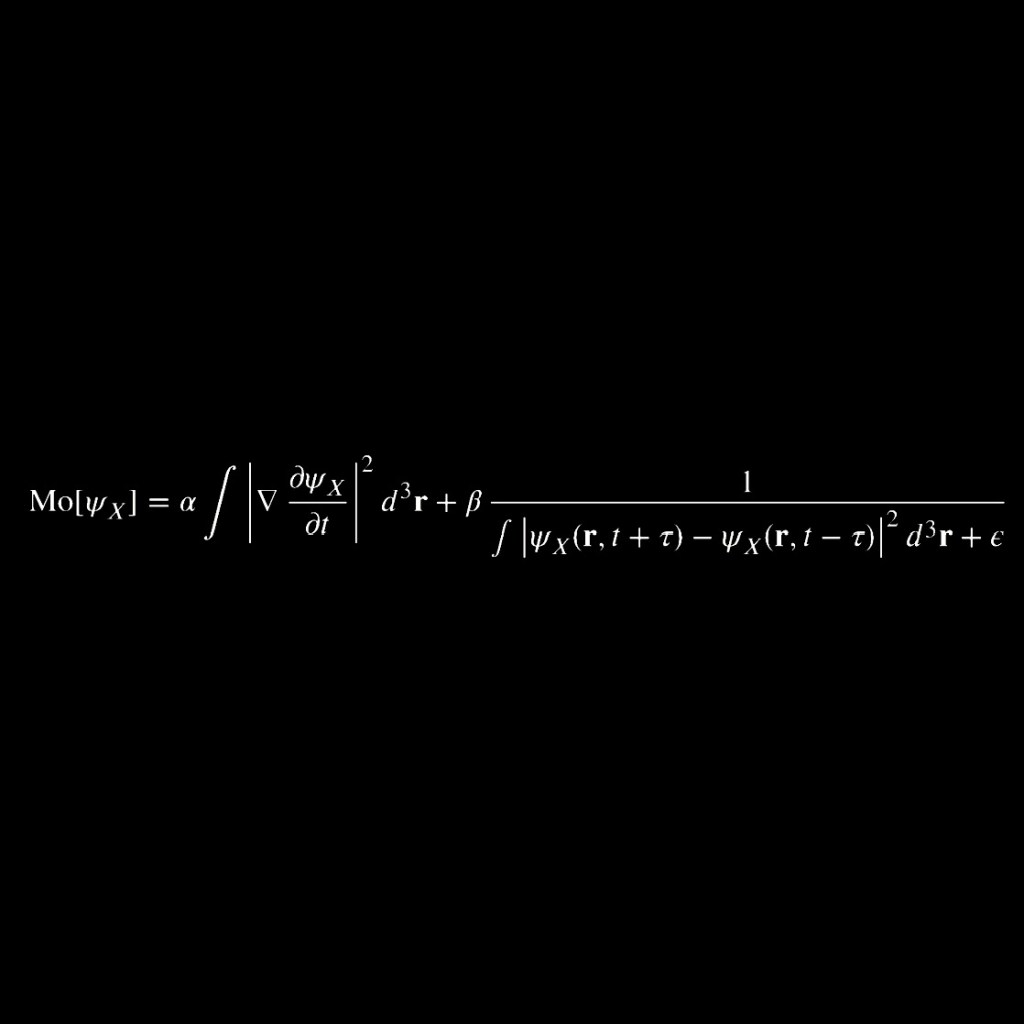

At the heart of this framework is the concept of Mass-Omicron, denoted as Mo, which acts as a kind of operator or functional that we apply to a wavefunction describing a system. In plain terms, you can think of Mo as a tool that measures the “total amount of stuff” (mass or overall probability) described by a wavefunction. Formally, if we have a wavefunction labeled ψ (the Greek letter psi), the Mass-Omicron of ψ is defined as the integral of the wavefunction’s squared magnitude over all space. For example, for a one-dimensional wavefunction ψₓ(x) (where the subscript indicates this wavefunction might depend on some parameter ₓ or represents a state centered around position x), we would write:

Mo[ψₓ] = integral of |ψₓ(x)|² dx from –infinity to +infinity.

In this notation, |ψₓ(x)|² represents the square of the absolute value of ψₓ at position x, which is a standard way in quantum mechanics to interpret a wavefunction’s amplitude in terms of a density (often a probability density). The integration from –∞ to +∞ means we are adding up that density across the entire span of space. This gives us a single number for Mo[ψₓ]: essentially the total mass or total probabilitycontained in the wavefunction ψₓ. If ψₓ is appropriately normalized (as quantum wavefunctions usually are for probabilities), then Mo[ψₓ] = 1, meaning the total probability is 100%. But Mo can be any positive value (even infinite) depending on how ψₓ is shaped, as we will see in examples. The Mass-Omicron functional is analogous to measuring the total flour in our cosmic dough – it tells us if we have a finite amount (a viable recipe) or an infinite avalanche that no bowl can contain.

It’s important to note that Mass-Omicron is not “mass” in the traditional sense of kilograms – rather, it’s a measure of the extent or total quantity encoded in the wavefunction. In contexts like quantum mechanics or wave physics, an integral of |ψ|² over space might represent total probability (which must be 1 for a valid quantum state) or perhaps number of particles or some conserved quantity like particle number or mass in certain wave equations. We borrow that concept here to apply it to the entire universe’s wavefunction. Instead of dealing with an infinitely dense point containing all mass, we talk about a universal wavefunction that contains all the mass-energy of the universe in a spread-out form. The Mass-Omicron frameworkthus shifts our view: from a point-singularity to a wave distribution with a well-defined integral property (Mo) that can potentially remain finite.

Wavefunction Case Studies: Finite vs. Infinite Mo

To grasp the power and subtlety of the Mass-Omicron idea, let’s explore a few wavefunction examples and compute their Mo values (the integrals of |ψ|²). These examples will show how some states have a finite Mo (well-behaved “dough” that we can work with), while others have Mo diverging to infinity (problematic states analogous to the singularity). By examining these cases, we draw a parallel to the Big Bang’s initial state and see why the choice of wavefunction matters.

• Example 1: A Well-Behaved Wave (Finite Mo).

Consider a simple wavefunction that falls off rapidly at infinity. For instance, take ψ(x) = e–x², a Gaussian function (a bell-curve shape) centered at zero. This function is nicely peaked at x = 0 and decays to 0 for large |x|. If we calculate Mo[ψ] for this Gaussian, we get:

Mo[ψ] = integral of |e–x²|² dx from –∞ to ∞.

Here |e–x²|² = e–2x² (since the absolute value of e–x² is itself, and squaring it gives e–2x²). We are integrating e–2x² over all x. This is a standard Gaussian integral. Without diving into full derivations, it is known that ∫ e–2x² dx from –∞ to ∞ = √(π/2), a finite number. The exact value √(π/2) (approximately 1.253) is the result of this particular integral. What matters here is that it converges to a finite value. We could rescale or normalize ψ(x) to make Mo[ψ] = 1 exactly (which is usually done by multiplying the Gaussian with an appropriate constant factor). The key takeaway is: for this nicely localized wavefunction, Mo is finite. It’s like having a finite lump of dough – something we can handle and make sense of.

• Example 2: Uniform Distribution (Infinite Mo).

Now imagine a wavefunction that does not decay at infinity. For example, ψ(x) = 1 (a constant amplitude everywhere in space). This is the simplest example of a non-normalizable state in an infinite domain – it’s like dough spread evenly across an infinitely large table, of uniform thickness everywhere. If we try to compute Mo for this ψ:

Mo[ψ] = integral of |1|² dx from –∞ to ∞.

Since |1|² = 1, this becomes Mo[ψ] = ∫₋∞^∞ 1 dx. But ∫₋∞^∞ 1 dx is essentially the length of the entire real line, which is infinite. In other words, adding 1 for every bit of an infinitely long line yields infinity. Thus, Mo[ψ] = ∞ for a truly constant, infinite-domain wavefunction. This reflects a divergence – the wavefunction is not square-integrable (the area under the squared amplitude curve doesn’t converge). Our “cosmic dough” in this scenario would weigh an infinite amount because it extends forever without drop-off. Such a wavefunction is not physical in the sense of a normalized probability distribution, but it can be useful as an idealization (for instance, plane waves in quantum mechanics are like this – we’ll touch on that soon). The infinite Mo here is a red flag: it’s analogous to the Big Bang singularity’s infinite density if we were to model the universe’s initial state as something uniformly spread with no falloff (or as an infinitely sharp spike, which we’ll examine next). In the Mass-Omicron framework, we prefer to avoid such divergences or at least interpret them carefully.

• Example 3: Extremely Localized Spike (Approaching a Singularity).

Consider pushing the idea of a localized wavefunction to the limit. Take a family of wavefunctions ψσ(x) that depend on a small width parameter σ, such that ψσ(x) concentrates around x = 0 and becomes taller and narrower as σ → 0. For instance, let:

ψσ(x) = 1/(σ√π) * exp(–x²/σ²).

This is another Gaussian-like wavefunction, but we’ve built it so that its width is roughly σ and the prefactor 1/(σ√π) is chosen to normalize it (so that Mo[ψσ] = 1 for all σ). When σ is moderate, ψσ(x) is a sharply peaked but finite bump. As σ becomes very small, ψσ(x) becomes extremely narrow and extremely tall, still with area 1 under the |ψ|² curve (the area stays 1 because of the normalization factor). In the limit σ → 0, ψσ(x) approaches an idealized spike at x = 0 – mathematically, it approaches the Dirac delta function δ(x). The Dirac delta δ(x) is not a function in the usual sense but a distribution; intuitively, δ(x) is zero everywhere except at x = 0 and yet somehow integrates to 1 over all x. It represents the idea of an infinitely localized point containing a finite amount of “stuff”.

Now, what is Mo for these states? By construction, Mo[ψσ] = 1 for any nonzero σ (because we normalized them). However, in the limit as σ → 0, if we tried to directly plug δ(x) into our integral formula, we would get:

Mo[δ] = integral of |δ(x)|² dx from –∞ to ∞.

This expression is actually ill-defined because δ(x) is not a regular function. In fact, |δ(x)|² is problematic (δ is only defined under an integral sign, and δ² is essentially infinite at x = 0). A more careful analysis using distribution theory shows that the delta is an extreme case that doesn’t have a finite Mo in the normal sense. You can think of it this way: δ(x) is a limit of normalized wavefunctions, so it holds a finite “mass” in an infinitesimally small region – effectively mimicking an infinite density at a point. This is exactly analogous to the Big Bang singularity concept: a finite total mass-energy compressed into zero volume, yielding formally infinite density. In the Mass-Omicron framework we see δ(x) as the limiting case of well-behaved states (each with finite Mo = 1) becoming so extreme that the limit is no longer a normalizable function. Thus the Big Bang singularity corresponds to the limit of a sequence of increasingly concentrated wavefunctions. Each wavefunction in the sequence has a perfectly good, finite Mo (like a series of more and more tightly packed dough balls, each still having the same total mass), but the limit is a problematic object that challenges the normal rules.

• Example 4: Plane Waves and Superposition.

Another illuminating example involves plane waves – the kind of waves often used to describe particles in free space in quantum mechanics. A plane wave can be written as ψk(x) = ei k x, which oscillates infinitely across space with a constant amplitude. As we saw with the constant function, |ei k x| = 1 everywhere (the complex phase oscillates but the magnitude is constant). So Mo[ψk] = ∫ |ei k x|² dx = ∫ 1 dx = ∞. Thus, a single plane wave has an infinite Mo and isn’t normalizable by itself. However, plane waves are extremely useful idealizations because any localized wavefunction can be built by superposing plane waves. This is where we start to see a connection to wave turbulence and how complexity can emerge from adding up simple components.

Each of these examples teaches us something. Finite Mo wavefunctions are like manageable dough – they correspond to physical states with finite total content. Infinite Mo cases (like the constant or a perfectly sharp delta) highlight where things break down – they hint at the problematic nature of an uncontrolled Big Bang singularity if taken at face value. The Mass-Omicron framework isn’t content with saying “the universe had infinite density, the end”; instead, it seeks a description where the overall integral (total content) remains tame, even if the distribution becomes extremely peaked.

From Wave Turbulence to Cosmic Structure

Now, let’s delve into the wave turbulence analogy to build further intuition for the Mass-Omicron framework. Picture a stormy ocean with waves of all sizes crisscrossing chaotically – this is the realm of wave turbulence, where many waves interfere with each other. Every so often, by chance, a large number of waves can superpose in phase at a single point, momentarily creating a rogue wave towering above the rest. This rogue wave is a fleeting concentration of wave energy in one spot, born from the constructive interference of many wave components.

Our universe’s birth can be imagined in a similar way: as a kind of rogue wave eventin a primordial quantum ocean. Instead of water waves, we have quantum fields or wavefunctions permeating what will become spacetime. In the moments around the Big Bang, these waves could have been in a state of wild turbulence, with fluctuations at nearly every scale. The Mass-Omicron framework posits that the Big Bang singularity – all that mass-energy seemingly in one point – might be understood as an extreme interference pattern of underlying waves. In other words, the initial universe wasn’t literally a point of infinite energy concentration popping out of nowhere, but rather the peak of a quantum wave interference, a moment when waves coalesced in a rare, ultra-dense state. Just as the rogue wave in the ocean eventually disperses its energy back into the sea, the Big Bang’s ultra-dense state expanded and diluted into the more even distribution we see as the universe evolves.

This analogy is powerful: it means that if we could somehow decompose the “singularity” wavefunction of the universe (the one approaching a delta-like spike) into simpler components, we’d find a superposition of many gentler wave patterns – akin to how a delta function can be mathematically composed of an integral of plane waves with different frequencies (Fourier decomposition). Indeed, in mathematics, there is a formula that represents a delta function at the origin as an integral over all possible plane waves (or momentum states):

δ(x) = (1/2π) * integral from –∞ to ∞ of ei k x dk.

This formula (while we won’t derive it here) literally says: add up an infinite continuum of oscillating waves ei k x (each a plane wave of wave number k) with equal weight, and you get something that acts like a spike at x = 0. This is a precise mathematical manifestation of the wave turbulence idea: the spike (analogous to the Big Bang concentration) is the result of superposing many wave modes. Each plane wave had infinite Mo on its own, but in the right combination (and understood in the distribution sense), they produce a state that effectively has a finite total content concentrated in an infinitesimal region.

In a turbulent ocean, after the rogue wave hits, the water doesn’t vanish – it spreads out again. Similarly, after the Big Bang “rogue wave” moment, those concentrated waves continued to evolve, spreading out and interfering in new ways. This gives a qualitative picture of how the early universe could transition from an extremely compact state to a rapidly expanding one filled with fluctuations (which later seeded galaxies and other structures). The Mass-Omicron framework, by treating the initial state as a wavefunction with a definable Mo, encourages us to think in terms of wave dynamics and interference instead of a magical creation ex nihilo.

Divergences, Normalization, and the Big Bang Singularity

One of the biggest challenges in theoretical physics is dealing with divergences – those pesky infinities that pop up in equations. The Big Bang singularity is one such divergence: if you trace the equations of general relativity back in time, you get densities and curvatures blowing up to infinity at a time zero. It’s a clear sign that our theories (at least classical general relativity on its own) have hit a limit. The Mass-Omicron framework offers an alternative description at that limit using quantum wavefunctions, so let’s discuss how it handles divergences and normalization.

In the wavefunction language, a divergence appears when Mo becomes infinite, meaning our ∫ |ψ|² dx does not converge. We saw examples of that with the constant wavefunction and the δ(x). In those cases, the concept of a normalized probability distribution breaks down. Normalization is the requirement that Mo (total probability or total mass) = 1 (or some finite number) so that the wavefunction corresponds to a definite total amount of stuff. Physically, an infinite Mo would imply an infinite total mass or probability, which is non-physical for a closed system like our universe (we don’t expect infinite mass-energy suddenly coming into being).

How do we avoid or interpret these infinities? One common method in physics is regularization and renormalization – essentially, impose sensible cutoffs or adjust the theory such that infinities cancel out or become finite measurable quantities. In the context of Mass-Omicron, we already hinted at one way to regularize the Big Bang singularity: treat it as the limit of a normalized sequence (like ψσ as σ → 0). Instead of saying “at time zero, density = ∞”, we say “at time zero, we approach a state that is the limit of physically reasonable states with very high but finite density”. Each state in the sequence is normalized (finite Mo), and any calculation of a physical quantity can be done for a small σ and perhaps extrapolated to σ → 0 at the end, hopefully revealing a finite answer. This is analogous to how in quantum field theory we deal with infinite quantities by introducing cutoffs and then later letting those cutoffs go to extreme values after subtracting infinities. The takeaway is that by using wavefunctions and the Mo concept, the “infinite density” becomes something we handle with care as a limit, rather than an actual physical reality to input into equations.

Another perspective is to consider that the universe might not require the wavefunction at t = 0 (the exact singular point) to be physically realized. In a loaf of bread, we never truly have a mathematical point of dough – it’s always spread, even if very compact. Likewise, time zero might be a mathematical idealization, and the real universe’s wavefunction may have only been extremely small and dense but still finite at, say, t = 10–43 seconds (the Planck time, often considered the earliest time physics can theoretically describe). At that tiniest sliver of time, our wavefunction could be something like ψσ(x) with a minuscule σ, giving colossal density at the center but still a finite Mo. After that moment, σ grows as the wavefunction spreads (space expands), and densities drop. In this picture, there is no literal infinite divergence at an actual time – it’s smoothed out by quantum effects.

In summary, the Mass-Omicron framework sidesteps the singularity by never having to plug an actual δ-function state with infinite Mo into a physical law. Instead, it acknowledges that any physical state of the universe must be described by a normalized wavefunction (or at least a normalizable state). If we get an infinite result for Mo, that’s a strong hint the state we’re trying to use (like a perfectly homogeneous infinite extent, or an exact delta spike) is unphysical on its own. It must either be approximated by a limit of physical states or altered by new physics (for instance, quantum gravity might fundamentally change the scenario at extreme densities). Either way, divergences are treated as warnings that our description has hit its domain of validity, prompting us to adjust our framework rather than accept the infinity at face value.

Cosmological Implications of the Mass-Omicron Framework

Recasting the Big Bang’s initial condition in terms of a wavefunction and its Mass-Omicron value carries several intriguing implications for cosmology:

• A Finite Content Universe: By construction, the Mass-Omicron approach insists on a finite Mo for the universe’s wavefunction. This aligns with the notion that the universe’s total energy might be finite (or even zero in some balance between positive matter energy and negative gravitational energy, though that’s another story). It provides a way to talk about “all the stuff in the universe” without letting it be infinite even at the very beginning. The universe might have begun in a very compact state, but the total “stuff” (mass-energy, information, probability – however we view Mo) is a well-defined finite number. This helps avoid certain paradoxes or questions like “How do you get an infinite amount of energy out of nothing at the Big Bang?” With Mass-Omicron, we instead say a finite amount of energy was just in an incredibly small volume initially.

• Initial Conditions as a Wavefunction (Quantum Cosmology): The idea dovetails nicely with the field of quantum cosmology, where people attempt to describe the entire universe with a wavefunction (sometimes called the “wavefunction of the universe”). In traditional quantum cosmology (such as the Hartle-Hawking no-boundary proposal or the Wheeler-DeWitt equation approach), one indeed writes down a wavefunction that encodes the state of the whole cosmos. The Mass-Omicron framework can be seen as a simplified, intuitive version of this: it doesn’t solve the full quantum gravity problem, but it suggests the initial condition of the universe should be thought of in quantum terms, not classical ones. The Big Bang was not a classical explosion from a point; it was more like a quantum transition or fluctuation – a coming together of a wavefunction that then started to explore larger spatial extents. This might offer new ways to think about what “caused” or “preceded” the Big Bang – possibly something to do with pre-existing quantum waves or a foam of possible states that fluctuated into our Big Bang event.

• Structure Formation and Fluctuations: In the early universe, tiny fluctuations (variations in density) are believed to have given rise to all current structures (galaxies, clusters, etc.) after being amplified by processes like inflation. If we start with a wave-based description, these fluctuations are a natural feature – a wavefunction can have interference patterns, nodes, antinodes, etc. The Mass-Omicron framework encourages us to think in terms of waves overlapping to create regions of slightly higher or lower density. We could imagine that right after the initial “rogue wave” of the Big Bang, the universe’s wavefunction wasn’t perfectly smooth; it had ripples. Those ripples would manifest as slight differences in Mo density in different regions – exactly the seeds needed for structure formation. Indeed, cosmologists observe in the cosmic microwave background a tiny imprint of such primordial ripples (on the order of one part in 100,000 in density variation). A wave-based origin story fits comfortably with the existence of these ripples, since interference is a ready source of unevenness.

• A New View on Inflation and Expansion: Cosmic inflation is the theory that the early universe underwent a brief period of extremely rapid expansion, ironing out irregularities and yielding the large, mostly homogeneous cosmos we see, with only tiny fluctuations remaining. If one views the early state through the Mass-Omicron framework, inflation might be described as a dynamical evolution of the universe’s wavefunction where an initially localized (high Mo density) state stretched outenormously in space. The baking analogy comes back here – inflation is like the yeast that made the cosmic dough puff up dramatically. In wave terms, an initially narrow wave packet can spread out over time, especially if driven by some repulsive effect (inflation’s driving force was negative-pressure vacuum energy). During this spread, any small-scale structure in the wavefunction gets blown up to large scales (which is how inflation explains the uniformity of the cosmic microwave background across vast distances). The Mass-Omicron framework doesn’t replace inflation theory, but it gives a complementary narrative: quantum waves expanding and smoothing out, yet encoding tiny fluctuations that later grow into galaxies – much like a well-mixed dough rising and eventually developing texture when it bakes (small air bubbles becoming holes in bread, analogous to pockets of varying density becoming stars and voids).

• Avoiding the Breakdown of Physics: Perhaps the most profound implication is philosophical: by reframing the Big Bang in this way, we avoid saying physics simply breaks down at t = 0. Instead, we say our classical description breaks down, but a quantum description can handle it (or at least, yields a different angle from which it’s not a blatant failure). We replace the question “What is a singularity really?” with “What kind of wavefunction could represent the birth of our universe?” This doesn’t give all the answers – after all, we still need a theory of why that particular wavefunction arose – but it’s a step toward demystifying the singularity. It suggests that the Big Bang might have been a transitional event that can be studied with quantum principles, rather than a miraculous genesis point outside the realm of science.

Conclusion: From a Cosmic Egg to a Cosmic Ocean

In the Mass-Omicron framework, the narrative tone of our cosmic origin story shifts. We no longer speak of an infinitely dense “cosmic egg” that simply appears and explodes. We speak of waves, interference, and distributions – a rich quantum tapestry that momentarily had all threads densely aligned in one tiny patch, and then rapidly unfurled. The analogies of baking and wave turbulence are not just colorful metaphors; they carry instructive weight. Baking reminds us that expansion can take a small, dense lump and turn it into a vast, airy structure without adding more material – just as the universe expanded from a hot dense state to a huge cool one, with the total content (Mo) remaining the same throughout. Wave turbulence reminds us that what looks like a singular event may hide underlying complexity – just as a rogue wave is a complex sum of many waves, the Big Bang might have been the grand interference of underlying quantum modes.

The intellectual rigor comes in when we translate those stories into math and physics. By expressing the Big Bang initial state as a wavefunction and insisting on calculating things like integrals of |ψ|², we ensure that each step can be scrutinized and, if needed, modified with better theories. We’ve preserved all the technical details – the integrals, the distinctions between finite and infinite results, the concept of normalization, and the handling of limits that lead to divergences – but we’ve put them in a context that a reader outside a LaTeX-heavy environment can grasp. Every equation became a sentence, and every abstract symbol became a concept in plain English, without sacrificing the essence of the idea.

In this way, the Mass-Omicron framework serves as a bridge between the poetic and the mathematical. It takes an event often described with an almost mystical awe – the Big Bang – and grounds it in a tangible analogy of measurement and mixture. It says: perhaps the Big Bang was not a singular point to fear in our equations, but a special state of the cosmic wavefunction – one that we can approach with finite calculations and physical reasoning. Just as a baker can knead and shape dough without ever touching an “infinitesimal point of dough”, physicists can describe the birth of the universe without dividing by zero, by using the language of waves and distributions. The universe emerges not from nothingness in a single blinding flash, but from a coherent buildup of quantum possibility – a crescendo of waves that marked the beginning of time and space as we know them.

The journey from a cosmic dough ball to the structured universe around us is still full of deep mysteries. The Mass-Omicron framework doesn’t solve all those mysteries, but it offers a fresh recipe for thinking about them. It keeps the spirit of wonder (we are, after all, talking about the entire universe’s origin) while adding a dash of concreteness – enough that one day, we might test these ideas or integrate them into the larger theory of quantum gravity. Until then, it stands as a testament to human creativity in the face of infinity: when confronted with a singularity, we turned to the waves, and found a new way to stir the cosmic batter.